Joaquim Arena’s Under Our Skin, translated from the Portuguese by Jethro Soutar, an investigation into the remarkable lives of João de Sá Panasco, Thomas-Alexandre Davy de la Pailleterie, Andresa do Nascimento, and Marcelino Manuel da Graça, to name just a few of the historical figures profiled in this stunning book on the African diaspora in Portugal, could not have come at a better time—just as I have been reading about Juan Latino, Charles Graves, Mary Wilhelmina Lancaster, and Priscilla Henry, equally impressive figures of the diaspora in Spain and the United States. In addition to leading me through the lives of these key figures as they intersected with the course of History and came to be represented in the arts, Arena, whose book begins with his return to Portugal from his home in Cabo Verde after the death of his adoptive father, also grounded me by creating a striking sense of place. Consider his description of Alcácer do Sal: “But there’s something alluring and hospitable about the place too, as if its shadowy streets guard ancient secrets. The castle on the hill, the al-qasr (‘the castle’ in Arabic) that gives the town its name (along with sal, the Portuguese word for ‘salt’), watches over the floodplains, vast and lushly green, and looks down on the white town that climbs the slope from the river. The place has been the scene of historical battles, invasions, clashes between great empires and civilizations, and this knowledge undercuts the sleepiness with a sense of import.” Passages like this one, wonderfully mediated by Soutar, keep me returning to Arena’s book and contemplating the various groups of people that carried their languages, customs, and chattel atop a hill in the Iberian Peninsula and made something happen. Arena’s book reminds us that what was made can be unmade if we, like his friend Leopoldina (also profiled in this book), understand how things came to be. In that regard, I think that Louis Timagène Houat’s The Maroons, which tells the story of Frême and Marie’s escape from slavery and introduction into a maroon community in a forest on Réunion Island—translated by Aqiil Gopee and Jeffrey Diteman—is a good harbinger for 2024.

—Alexander Aguayo, Editorial Fellow

It’s been a hard time to read for pleasure, but who do I turn to in periods of despair and dissonance but our poets? These days, I’ve been reading and reading “Good Morning Gaza,” Fady Joudah’s recent translation of a 1984 Mahmoud Darwish elegy (published in The Baffler) and thinking about how we are allowed to mourn in language, about audience, and about our names. I’ve also been thinking about breaches in history via Ida Börjel’s MA in Jennifer Hayashida’s translation (published recently by Ugly Duckling Presse). MA, released in the Swedish in 2014, was written in what the poet calls a “mesh of traumas, of catastrophes” and calls out the names and the places of our dead, a fever-dream list of losses in the tradition of Inger Christensen’s alphabet. But it is also very much a contemporary echolalia of our collective failing and grief. Right now, my eyes rest on the lines from the title-poem: “what is left here / it is heavy / it is very difficult to be in.”

I’m one of those readers who cherish being guided by their favorite translators to discover new writers. So, after being blown away by Jayasree Kalathil’s translations of Sheela Tomy’s Valli and S. Hareesh’s Moustache, I’m looking forward to her new work to be published in India in early 2024: Maria O Maria, Malayalam writer Sandhya Mary’s first novel. I’m also looking forward to the poetry offerings from trace press.

—Sohini Basak, Poetry Editor

Finally, I feel compelled to declare how much I—along with my five- and three-year-old children—enjoyed Monster-Scared, an entertaining tale on being scared of monsters in the dark (and in the attic). A book by Betina Birkjaer and illustrated by Zarah Juul, my boys delighted in everything from the storyline to Katrine Øgaard Jensen and Orien Longo’s pitch-perfect English translation. (At least a month since the last reading, they continue to run around declaring their intent to raise “a hullabaloo racket.”)

As for 2024, I’m eager to read Otohiko Kaga’s epic novel Marshland, in a translation by Albert Novick (check out a review on WWB). Billed as “Tolstoyian,” the novel runs from the period before WWII into the 1960s. Writing in WWB, critic Jack Rockwell writes that “[t]he result of Kaga’s effort is a sprawling indictment of modern society’s modes of organizing bodies and labor.” The book is finally slated to come out in January after some pandemic-related delays.

—Eric M. B. Becker, Digital Director and Senior Editor

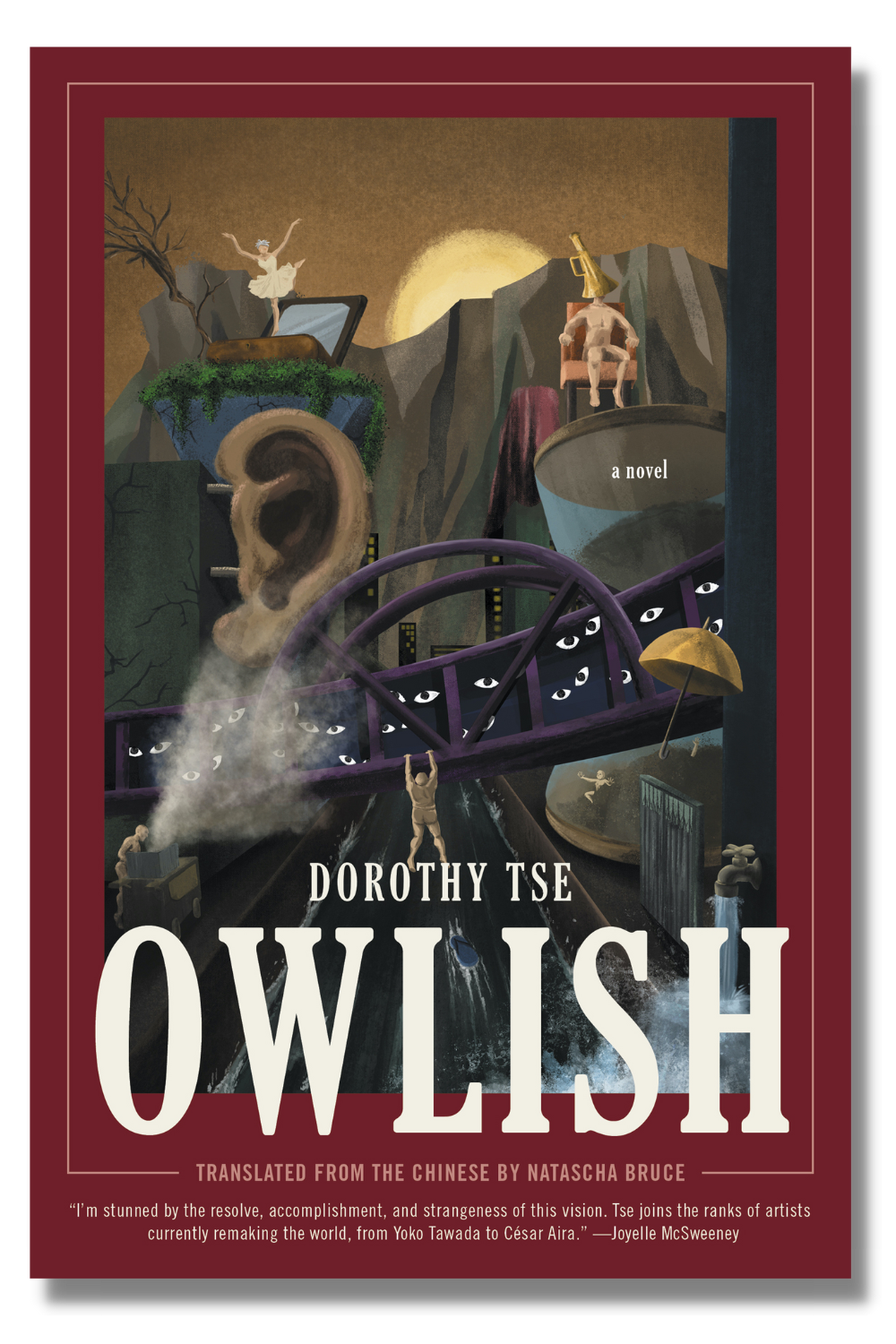

When I wrote about Dorothy Tse’s novel Owlish (translated by Natascha Bruce) back in June, I said that it was “nearly impossible to pin down.” Six months have passed and I’ve found the book to be even more elusive, which makes it eminently suited to the current moment. This is a book in which art can be both a refuge and a source of pain, set in a world where reality feels malleable and the consequences of making an incorrect decision can be catastrophic. In other words, it might just be 2023 in book form.

Next March brings with it The Inhumans and Other Stories: A Selection of Bengali Science Fiction, an anthology edited and translated by Bodhisattva Chattopadhyay, via MIT Press’s excellent Radium Press imprint. This includes the first-ever English translation of Hemendra Kumar Roy’s title story, along with several other works of Bangla speculative fiction from the first half of the twentieth century (and, in one case, even earlier)—all of which should make for a welcome expansion of speculative fiction for anglophone readers.

—Tobias Carroll, Watchlist Editor

It is so rare to be absolutely shocked by a novel—when The Love of Singular Men arrived, I was initially drawn in by the incredibly positive blurb from Zadie Smith. But somehow, I was still caught totally off guard: what a fun, unsettling, and bold book this is! It breaks every form (necessitating a virtuosic effort by the translator, James Young) from the line level to the scaffold, with illustrations and lists and photographs along the way. Victor Heringer tells a queer story of love and heartbreak that’s at once familiar and unique. There’s one section that I can’t let go of that ripples uncannily into the real world, the result of a public request to readers to share the name of the person they love. Heringer died very young and very tragically—I didn’t know to miss him, because I had never heard of him until I read this novel. But I miss him now.

I love everything Elisa Shua Dusapin and translator Aneesa Abbas Higgins create—their Winter in Sokcho was my favorite book of the last few years, and The Pachinko Parlor was a terrific follow-up. Dusapin’s novels are slim, brilliant studies that explore language, place, doubling, and longing. Vladivostok Circus looks like it’s going to take these elements and add in a Russian backdrop—I can’t wait for May!

—Adam Dalva, Books Editor

This year saw the publication of two books on the unfathomable act of infanticide (coinciding with the US release of Alice Diop’s film on the topic, St. Omer). Both tell the story from the perspective of an observer with a startling personal connection to the accused, and both interrogate the legal and moral elements of the crime in their search for the truth. In Katixa Agirre’s Mothers Don’t, translated from Spanish by Katie Whittemore, a writer and mother-to-be realizes she knew the defendant when they were both teenagers; in Marie Ndiaye’s Vengeance Is Mine, translated from French by Jordan Stump, the accused murderer’s attorney attempts to recover a disturbing childhood memory stirred by her client’s husband. Although the protagonists are quite different, their immersions in each case reflect their own fears and unanswered questions about not only motherhood but also parenting, family, and the inescapable past. (NDiaye wrote the screenplay for St. Omer, but the plots of film and novel differ.)

Of the many good books ahead in 2024, I’m looking forward to Jennifer Croft’s The Extinction of Irena Rey, as well as Antonia Lloyd-Jones’s translation of Witold Gombrowicz’s The Possessed, the first to be made directly from the Polish original. (Yes: impossible as it seems with the current wealth of brilliant Polish-to-English translators, Gombrowicz and many other crucial earlier Polish works appeared in English only via the French editions.)

—Susan Harris, Editorial Director

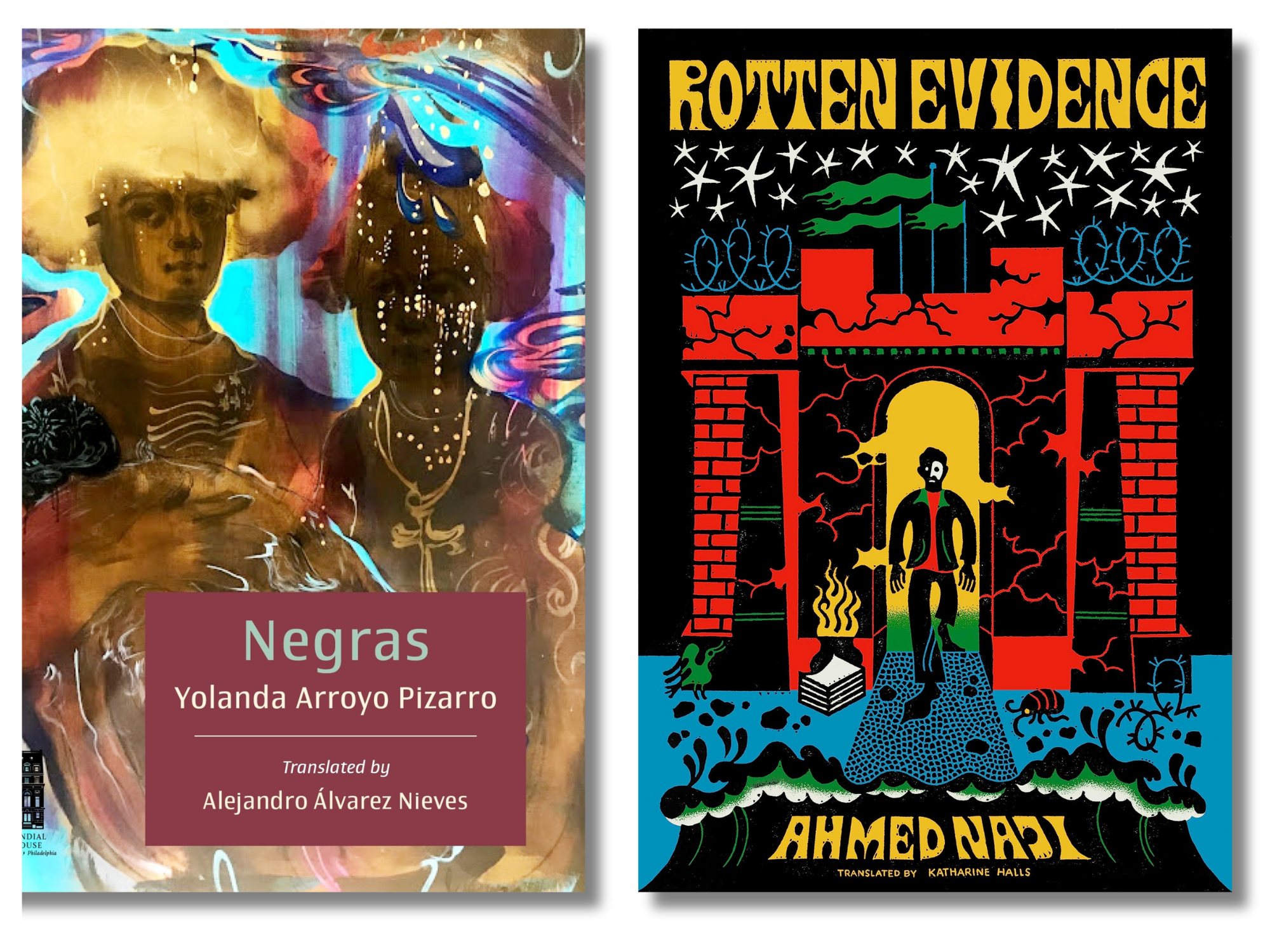

Those looking for light and cozy holiday reading are probably in the wrong place, as this year, I’m recommending two books about captivity: Yolanda Arroyo Pizarro’s story collection Negras and Ahmed Naji’s memoir Rotten Evidence. Both books are astounding and somehow exhilarating despite their subject matter; maybe it’s the palpable freedom of the narrative voices.

Arroyo Pizarro’s Negras recently came out in in a new bilingual edition from Sundial House of Columbia University Press, translated by Alejandro Álvarez Nieves. The book tells the imagined stories of four women living under slavery in the colonial-era Caribbean, focusing on the ways they find to rebel against their captors—from calling out a mother’s name to murdering Black infants bound for slavery. The language is at once lyrical and matter-of-fact, making this book unlike anything else I have read.

From McSweeney’s, Ahmed Naji’s Rotten Evidence is equally fearless: a prison memoir that takes shots at its own genre and relentlessly dismantles any tendencies towards self-pity or exceptionalism. The narrator’s compulsively honest and resolutely humble voice forges an immediate connection with readers; Katharine Halls’s translation moves easily between literary gossip, Egyptian history, and toilet talk.

For next year, I’m excited about Forgottenness by Tanja Maljartschuk, in which a woman copes with Ukrainian and family history as well as, perhaps unsurprisingly, “a series of mental health maladies” (David Varno, PW, 9/15/23). Zenia Tompkins translated the novel from the Ukrainian; it will be published by Norton’s Liveright imprint.

—Nadia Kalman, Global Education Director

One of my top reads this year was Rachel Willson-Broyles’s translation of Ann-Helén Laestadius’s Stolen, a literary thriller about a family of indigenous Sámi reindeer herders in northern Sweden. We follow the protagonist, Elsa, over more than a decade, from the moment she witnesses the murder of one of her reindeer through her teenage years and into early adulthood. During this time, Elsa and her community try to maintain their traditional way of life in the face of climate change, discrimination from their Swedish neighbors, and repeated killings of their reindeer, to which the police respond with indifference (at best). Like all good thrillers, the book moves quickly, but what I most enjoyed were Laestadius’s complex, sympathetic characters and her nuanced portrait of a way of life under threat. For a taste of Stolen, check out this excerpt on WWB.

In 2024, I’m looking forward to Lucas Rijneveld’s My Heavenly Favorite, translated from Dutch by Michele Hutchison. Rijneveld’s novel The Discomfort of Evening was one of the most astonishing books I’ve read in the past several years, and one of the darkest. I expect this new novel to be just as brilliant and horrifying as its predecessor.

—Nina Perrotta, Editor and Development Manager

I’m driving all my friends and loved ones nuts because I can’t stop talking about Georgi Gospodinov’s Time Shelter (translated by Angela Rodel), in which a mysterious character by the name of Gaustin sets about creating meticulous, historically accurate period pieces in which to house memory-loss patients. The efforts spiral and multiply until entire nations are holding referenda on returning to their glory days, warring among themselves over which decade to go back to, which period costumes to wear and newspapers to reproduce. It’s a brilliant exploration of nationalism, political nostalgia, and the divides between Eastern and Western Europe. There’s something satisfying about its maximalism, the way Gospodinov clearly takes bemused, head-shaking joy as he riffs on all the details of the book’s pseudo-time travel. It has the quality of an inverse, nightmarish Invisible Cities, a traveloguish feast where all the food has been gathering dust in a can for a half-century.

For 2024, I’m excited about Paulina Chiziane’s The Joyful Cry of the Partridge, translated from Portuguese by David Brookshaw—which promises to be the kind of rigorous yet winding novel I’ve been looking for, both a dive back into Mozambican history and a whirlwind trip into the lives of its characters.

My favorite read of 2023 was Laurent Mauvignier’s The Birthday Party, a slow burn of a thriller translated by Daniel Levin Becker. The story unfolds over the course of a day in a rural French village, where a man is planning a small surprise birthday party for his wife. Little does he know that uninvited guests plan to crash the party, and the happy occasion gives way to a nightmarish home invasion. Mauvignier has a talent for switching perspectives at the most nail-biting moments and leaving the reader guessing at each character’s fate for chapters on end, which makes this 400-plus-page stream-of-consciousness novel difficult to put down. I recommend it to anyone who likes their books long, meandering, and very stressful.

Next year, I’m looking forward to reading WWB Campus favorite Iman Mersal’s Traces of Enayat (translated by Robin Moger), which is forthcoming in the US in April. Mersal’s genre-bending nonfiction pays homage to the Egyptian novelist Enayat al-Zayyat, who died by suicide at the age of twenty-seven. Mersal retraces the author’s short life, touching on marriage, identity, and mental health along the way.

—Maggie Vlietstra, Education Program Coordinator

Mariana Enríquez, always translated to English by Megan McDowell, is one of my must-reads, and Our Share of Night reminded me of how she’s one of the greats. A slow-burn horror that holds you by the throat—with one long, taloned hand—and tightens its vise over six hundred pages, taking the reader into haunted houses and bodies, cursed cults and conspiracies, the jungles of Argentina and the afterlife. It’s impossible to put the book down even as it cuts off your oxygen, impossible not to root for those struggling on the side of humanity even when it looks likely they’ll fail. It’s the fight that counts, and Enríquez and McDowell refuse to flinch away from it. (Bonus points if you go back to read “Adela’s House” in Things We Lost in the Fire after finishing Our Share of Night!)

No wonder I’m really looking forward to the latest volume in the Calico Series by Two Lines Press, Through the Night Like a Snake, which features short stories both written and translated by more top-tier names in Latin American fiction and horror, Enríquez and McDowell among them. I’m a huge Calico Series fan and treat them like Pokémon (you gotta catch ’em all).

—Anna Claire Weber, Marketing & Communications Manager

Copyright © 2023 by Words Without Borders. All rights reserved.