In May of this year, someone posted a prompt on a Reddit board: “What is the weirdest thing you had to do at someone else’s house because of their culture/religion?” Among the many thousands of replies, one was soon christened #Swedengate: a user described visiting a Swedish household as a child and being made to wait in a separate room while their friend ate dinner with his family. Other users chimed in with similar experiences of Swedish mealtimes. People on Twitter, once the conversation migrated there, were outraged. They roasted Swedish culture for what they took as stinginess and insularity: a glaring lack of hospitality that wouldn’t fly where they were from.

As #Swedengate intensified, media outlets like NPR and the Washington Post interviewed Swedish and Swedish-adjacent diplomats, historians, and ordinary citizens. Several interviewees objected to the dust-up, saying they’d had no personal experience of nuclear families excluding their guests from meals in Sweden. Others ventured that the practice, though it had once existed, was far from universal and long discontinued. The reaction I found most intriguing was from Swedish food historian Richard Tellström, who said that the issue at stake wasn’t inhospitality, but rather cultural conceptions of family life. Prior to the 1990s, he told the Washington Post, people in Sweden almost uniformly ate in their own homes. “You didn’t feed other people’s children—that would have been considered a sort of intrusion in another family’s life, with the subtext of ‘You can’t feed your children properly, so I will feed them.’”

During the social media pile-on, my own Twitter feed was mostly mocking and indignant: O the cruel and inhospitable Swedes! But I read a few responses that were more in Tellström’s camp, in that they picked up on larger cultural differences—and larger failures of imagination. Swedish poet and translator Johannes Göransson, for instance, remarked on how bizarre it felt to behold such outrage in people who had no experience with the culture they were berating. People do things differently in different places, plain and simple.

They do; we do. What it means to be a guest, what it means to be a host, what it means to attend to, and be tended to, and to be nourished, received, accompanied in the domestic space: these things are done differently and felt differently everywhere. And so are the expectations of their translation.

***

I haven’t really lived as an adult in the United States, my country of origin. Which means, among other things, that I haven’t been a host there: haven’t welcomed others into a home of my own, fed them, tried to make them comfortable in their chairs, given them a surface to sleep on. I have only been a guest in the home of my parents (which isn’t the home I grew up in), my brother, or my friends. It’s in the other two countries where I’ve lived since college—in Palestine, for over a year, and in Mexico, for over a decade—that I’ve been more consciously, and self-consciously, both a guest and a host. A guest, in the way that everyone who learns another language and inhabits another country becomes and remains one. A host, in that I have had the privilege of choosing to be “here,” of learning to inhabit this hereness over time, and to receive guests of my own.

I moved to Palestine because I was in love with a person and to Mexico because I was in love with a place. It embarrasses me a little, reducing both decisions to so breathy a verb, but it’s true—or true enough. Since childhood, I had harbored an urgent curiosity about Mexico, where my father’s mother was from and where one of her brothers lived. I was in a hurry to grow up so that I could go there (come here) on my own terms, as if I knew what those actually were. Palestine was a breathless, entirely accidental detour I found myself taking when I plunged into a relationship with S, a Palestinian student at the college I attended. On the cusp of graduation, he was weary of the United States and wanted to go home. Did I want to go with him?

I did. I didn’t know anything else, but I went. We lived first in Bethlehem, in the occupied Palestinian territories (OPT). S—born in Haifa, meaning he held Israeli citizenship and was afforded a level of mobility that Palestinians from the OPT are denied—took a bus every day, passing through a military checkpoint on the way to his NGO job in Jerusalem, and he also traveled widely for work. As soon as I arrived, then, I found myself keeping my own company far more often than I’d imagined: an anxious, sheltered, materially incompetent twenty-two-year-old who had never lived by herself, let alone with a partner; never cooked much of anything, let alone shopped for groceries in Arabic. On my first trip to the market, I returned with two kilos of tomatoes instead of the two tomatoes I’d intended to buy. This in itself was a lesson.

Who buys two measly tomatoes? What would you do with them?

***

For me, living in Mexico has gone hand in hand with living in Spanish and becoming a translator of both poetry and prose. I’ve translated authors from various countries, but the Spanish that makes me feel the most at-home-away-from-home is Mexican Spanish—and as I’ve written elsewhere, not just Mexican Spanish, but Mexico City Spanish, with its singular accents, cadences, profanities, and continual flux, none of which I will ever “master” (which reminds me that “mastery” is no longer the way I care to think about language, culture, or anything else). But my home is not just Mexico City Spanish, either, because I spent years with A, who grew up in the northern state of Coahuila, and there are times I’ll repeat something I heard him say and not even know it’s northern slang until someone from Mexico City giggles in response.

Translating prose, literary and otherwise, is how I make my living and spend most of my waking hours, although poetry is my first and most ardent love. Poetry remains the place—it has always felt more like a place than a genre to me—where I get most rapturously entangled in language. I’m intrigued by how many people, both those who read poetry and those who don’t, treat its translation as a fruitless endeavor, totally impossible, never mind that it’s been done across cultures and literary traditions for thousands of years. Transgressive Circulation, a brilliant book by Johannes Göransson, refuter of Swedengate, is among the works that have most informed my thinking about this supposed impossibility. In it, he discusses how a pervasive anxiety about poetry itself—long viewed as a “pure” form, a distillation of an essence, an unmediated expression of the poet’s subjectivity—has fomented distrust of translation in the US literary milieu. He also explores how the US canon has privileged a handful of recurringly-translated poets (Neruda, Paz, Tranströmer, Rilke) rather than encouraging the rich, energetic destabilization of other foreign writers whose work can’t be contained within the US American comfort zone. In the end, Göransson characterizes poetry and its translation as a crucial contaminant, an exuberant, transformative life force that disrupts long-prized ideas—ideals—of genius, individual authorship, literary lineage, and intellectual property. I think he’s right. Translation makes poetry vulnerable to the possibility of foreign influence. It makes it harder to distinguish the host from the guest.

***

Places I was a guest in Palestine: everywhere. In the home of S’s mother, a prodigious cook, fan of Turkish soaps and Princess Diana. At a Druze funeral in the occupied Golan Heights, sipping bitter coffee in a semicircle of plastic chairs. In the garden of Akiva, a founding member of the revolutionary socialist and anti-Zionist movement Matzpen, taking mushrooms together on the day between our respective birthdays: my twenty-third, his seventy-ninth. In a refugee camp whose name I’m ashamed to have forgotten, in the family home of, I think, a coworker of S’s, after a daylong barbecue where I’d drifted through the olive trees with someone’s baby in my arms. In the apartment of M, a Catalan NGO observer who was summarily deported after a visit to Gaza, bequeathing to us a corroded, temperamental rattletrap named Garfield. In the ground floor apartment we ultimately rented in Ras al-Amud, a neighborhood behind the Old City of Jerusalem, overlooking the resplendent dome of Al-Aqsa Mosque. Our landlord, a sweet-tempered patriarch, once stopped by for some reason or other—by this time I could carry on a basic conversation in Arabic—and asked me, winking, how my husband was: acknowledging the social expectations at hand, letting me know that he was perfectly aware we weren’t married and didn’t care.

Places I was a host in Palestine: on Star Street and on Al-Ghoul Street, where we received friends of S’s and friends of mine. Guests included W, our next-door neighbor in Bethlehem who was too polite to tell me he was allergic to tomatoes until I noticed his face reddening, his eyes puffing up. S’s mother, who marched in and rearranged our kitchen cabinets as briskly as if they were her own. E, my friend and first translation teacher, whom I timidly fed a plate of fluffy red rice before readying a mattress pad on the floor beside the space heater. Two delegates from Brazil’s Landless Workers Movement. The teenage brother of a childhood friend of S’s, the only member of his family granted a permit by the Israeli army to accompany his mother for a major abdominal operation in a Jerusalem hospital. He was a gentle kid, and far too large for our stiff little couch. That night, I was relieved to hear him snore.

I grew up in an affluent New Jersey suburb whose white residents prided themselves, loudly and often, on the diversity of the town, although the stark racial and socioeconomic segregation of my public high school told a different story. I also grew up in an intensely nuclear family. People came in and out—playdates, dinner guests, weekend guests—but they always felt like spokes in the wheel. We, the four of us, were the hub. My father was the stay-at-home parent and the cook. The solicitousness of his hosting style was my unconscious model when I first started receiving guests in Palestine. Are you hungry? I’d venture. I made cookies. Or thirsty? We have water, and beer, and I think orange juice . . . It was S who soon corrected me: Robin, don’t ask. They will always say no. As I visited more Palestinian households, I began to understand what he meant: pretty much as soon as you were inside, food simply appeared, tea, coffee, cookies, entire meals, instantaneous, ubiquitous. Have more, his mother would urge me, as would everyone else, and I too learned to refuse, refuse, while always accepting. Sometimes I was so full that the idea of eating anything else felt like a performance I resented, especially because I was shy, wracked with political shame, taciturn because I spoke Arabic like a preschooler and hated making S’s friends speak English with me. Sometimes I clicked into a state of silent defensiveness I hadn’t experienced in years, when I was a high school student with an eating disorder.

Looking back on these visits now, though—years after I left Palestine, years after the relationship was over, years after everything painful about the time began to dissolve into my bloodstream, no less a part of me, just invisible—I’m overcome with a stammering gratitude. It’s remarkable, really, to set foot into someone’s home as a stranger and be plied with food they’ve made. To focus your emotional energy on receiving: a form of participation that is necessarily unequal. Someday, you may have another chance to reciprocate: in another time, another place, another home. Yours. But you’re here now, so sit down and eat.

***

Translation, an obsessive interpretive art in which the boundaries between guest and host are tenderly and strenuously unstable, is my constant companion while I learn what it means to build a life in a country and culture different from the one I was raised in.

Where, in other words, you’re both: you know you are both guest and host at all times, though not necessarily in equal or stable measure. You’ll always be from somewhere else: molded by other histories, reduced to your oldest habits and your simplest words when tired or upset (guest). If you stick around long enough, you change: you both let it happen and reach for the transformation with your own hands, making a place for yourself (host). Presumably it will never be over, this hovering at the threshold of your own home. Which home? Any home.

And I love it. It keeps me awake and hungry and uncomfortable, keeps my senses humming, because it keeps me thinking less about how things are and more about how they came to be, and how easily they could have been otherwise.

At the same time, I rankle at the insinuation that translation or being a translator—or poetry and being a poet—is a moral good. That these things make you inherently more sensitive or more empathic. Or that empathy, for that matter, is in itself a supreme goal or a form of absolution. (“Empathy is emotional tourism,” says the poet Solmaz Sharif.) Translator and poet Mona Kareem has written about the contemporary trope of translation as both cool and redemptive, especially among white Western translators into English and their readers. “Where does this blind faith in translation come from?” she asks. “Doesn’t translation act also as unconditional access, as surveillance, as an expanding force of the global capitalist market of literature?”

It seems to me that English-language literary culture views translators as, predominantly, hosts. Translation as (forgive me for quoting this stalest of metaphors) bridge to another culture. Translator as organizer of a dinner party. Show and tell. Yet translation is not a discovery, nor a tray of hors d’oeuvres, but a collaboration, a making-from, a being-with. “Perhaps,” writes translator Jeremy Tiang, “if the dominant anglophone culture actually acknowledged itself to be part of the world, rather than treating ‘world literature’ as a spice rack to save itself from total blandness, more than three percent of books published in the United States would be in translation?”

Both ethically and aesthetically, I’m more compelled by the thought of translator as eternal guest. Or, at any rate, as the kind of guest-host forged by being a long-term inhabitant, an apprentice, a participant-observer in another place: an arrival that becomes an entire life. A life in which being a friend and neighbor defines your everyday reality, even your identity, more than anything else. When I translate, I am not merely a guest in the Spanish language or in the culture of the poem or story or novel I’m translating; I’m also made more aware of being a guest in my own. No: not my own, because I don’t own it. I translate into English not because it’s “mine,” my “mother tongue,” my “dominant” language, but because I have learned it immersively and will never stop learning it. I sleep in it, steep in it, speak and write myself into it. It is relentless, this learning, with my object of study neither English nor Spanish per se, but rather the material, ever-evolving relationship between the two. I am a guest in both houses.

***

Places I’ve been a guest in Mexico: everywhere. And yet it’s harder for me to distinguish my guestness from my hostness here, because here is home now. As an immigrant, I’ve felt myself becoming a hybrid of the habits inculcated in me by my environment of origin and the habits that I’ve either studiously or unwittingly absorbed over the past eleven years. I think of myself as a fairly reserved sort of person, but when I go back to the States and meet new people, I’m the over-emoter who’s always hugging everyone. In Mexico, friends and I will go Dutch when either of our respective budgets demands it, but it’s more common for us to take turns treating each other. Yo te invito, someone will announce, insisting sí sí sí when the friend objects, then relents: ¡pero la próxima vez me toca a mí, eh! I think of this ritual whenever I’m in the US and overhear someone venturing tepidly to their companion when, say, the bill arrives in a coffee shop: Uh, I can get this if you want. The displacement of the decision onto the ostensible object of the generosity. Living in Palestine and then Mexico has trained me to dispute such vacillations in more automatic and strenuous terms: no no no no, I’ll get it, I’m getting it! If asked, refuse: it’s the polite thing to do.

The code-lurching makes me think anew about US Americans’ preoccupation with choice, with preference, with shared social reality as a bouquet of individual decisions that are variously prioritized and articulated across the ideological spectrum. I should rephrase less sweepingly: the code-lurching makes me think anew about how I, too—growing up on the East Coast of the US without a sense of intergenerational cultural influence or any real conception of how my own nuclear family had been shaped in its social habits—bear the marks of American individualism, even in ephemeral, harmless, loving interactions. There’s no getting away from them, not entirely. They’re in me, however they may jumble together with the mores I’ve encountered since. Ni modo. They contain the kind of asking I first learned to do, the kind of invitations I first learned to extend, the kind of individual overture I first learned to externalize, eager to give and to please and to follow the rules—and to be perceived as doing all of the above. Can I get you something?

***

Lawrence Venuti, arguably the most visible of all translation theorists, has written at length about the historical invisibility (an attribution that evokes generations of hostesses laboring in the backstage that is the kitchen, or girls expected to feel like perpetual guests in public: better seen than heard) to which literary translators have been relegated and confined. Contributing to the insidiousness of this invisibility, he argues, is the expectation—bolstered by decades of MFA culture in the US and the “clean” style it privileges—that translators should “domesticate” their work stylistically, making translated texts sound “fluent,” pleasing to the ear, more palatable to the dominant US aesthetic. Of course, this expectation (and its execution) doesn’t only make translators fade into the background; it also hegemonizes the writers they’re translating. Göransson, writing specifically about poetry, agrees with Venuti’s take on the homogenizing bent of US literature. But he also takes issue, as do I, with an idea Venuti puts forth to counter the invisibility of translators and the aesthetic particularities of the texts they translate: rather than domesticating their English versions, Venuti believes that translators should “foreignize” them, calling attention to the translatedness of a text, teaching the reader a lesson about the limitations of Anglo culture.

Göransson argues that this approach backfires right away: by deliberately “foreignizing” their work, a translator risks “maintaining a border rather than allowing it to break down and generate dynamic uncertainty.” The point of translation is not to teach the reader a lesson; a translated text, Göransson stresses, is not a pedagogical tool for the express benefit of US American readers. In short: “The foreign text does not need to be made more foreign by the translator—the foreign text is already foreign.”

I hear this discussion in the key of host and guest. Venuti, even in a well-intentioned effort to diagnose a hegemonizing bias, still casts the translator as a host on a nearly parental power trip. Thanks for coming! Now eat your vegetables, they’re good for you. Göransson adds some guestness to the equation. It’s not that a guest has no power. Of course they do. A guest can step into someone else’s house and take it apart with their eyes. A guest can be rude or fawning, vivacious or withdrawn. Göransson, in collaboration with poet and translator Joyelle McSweeney, has written about translation as a “deformation zone,” in which violence is done not only to the original but also to the target culture—and to the translator. “That violence,” writes Göransson, “generated by the transgression of translation’s circulation, is not something we should attempt to protect poetry from; instead we should recognize it as poetry’s signature. We should accept and embrace it.” The host/guest relationship isn’t just a matter of sitting around and sipping tea. It also entails inevitable risks of vulnerability, invasiveness, uncertainty, and transformation. The foreign text is already foreign. And in translation, to borrow a phrase from poet Alice Fulton, “It will be new // whether you make it new / or not.”

***

I’ve been thinking about domesticating vs. foreignizing, and about what Venuti and Göransson have to say about them, because while I quickly rally against the latter, I’m not always sure I don’t do the former. This worries me. Most translators are sick of talking about fidelity and so am I. But I do care about respect. I want to respect the texts I translate, and I want my craft to show it. I want to be a good guest: observant, appreciative, offering both my company and my independence as proof of my trust.

Nonetheless, I sometimes overstay my welcome. Once, while working on my translation of Maricela Guerrero’s The Dream of Every Cell (Cardboard House Press), one of my editors (the wonderful Giancarlo Huapaya) drew my attention to a domesticating gesture I’d made. That’s not what he called it, but that’s what it was. Guerrero’s book intermittently draws on scientific and journalistic language to explore the relationship—violent, exploitative, and potentially still charged with wonder—between humans and the natural world. In sprawling lines that often splice grammatical phrases together, she repeats semantically kindred but not exactly synonymous words (“subtraction” and “extraction,” or “shared” and “communal”), like cells calling out to each other inside a single organism. Giancarlo pointed out that I’d started to collapse some of these near-synonyms together, treating them interchangeably, when he felt that Guerrero was very clear about when and how she used each individual term. He was right. So earnestly did I want my translation to dance as I was used to dancing that I’d succumbed to the temptation of smoothing the words out, flattening their eccentricities in favor of my own habits.

The solution also wasn’t to swerve in the other direction and deliberately “foreignize” my translation; as Göransson stresses, intentional foreignization runs the risk of committing another kind of domestication. It was just to identify and acknowledge the logic of the work itself (which, of course, is already itself), then make sure my translation followed it where it had already gone. After all, the allure of reciprocity isn’t so much the promise of giving and receiving in equal measure as it is the hope that both parties feel respected and treasured, able to be themselves. As translator-host, rather than bending the text to my will, I want to honor how it was made and why. As translator-guest, I want the independence to figure out both: why; how.

***

Among the sweetest ironies of hospitality is the honor of its overcoming. For both guest and host, it can be a thrill, or at least a relief, to feel so comfortable that the rituals of offering and receiving fall away. Someone shows up unannounced. Someone lets the other wash the dishes after dinner instead of theatrically insisting that they better not dare. Hospitality yields to friendship. That other pretext for translation. That other invisible home.

***

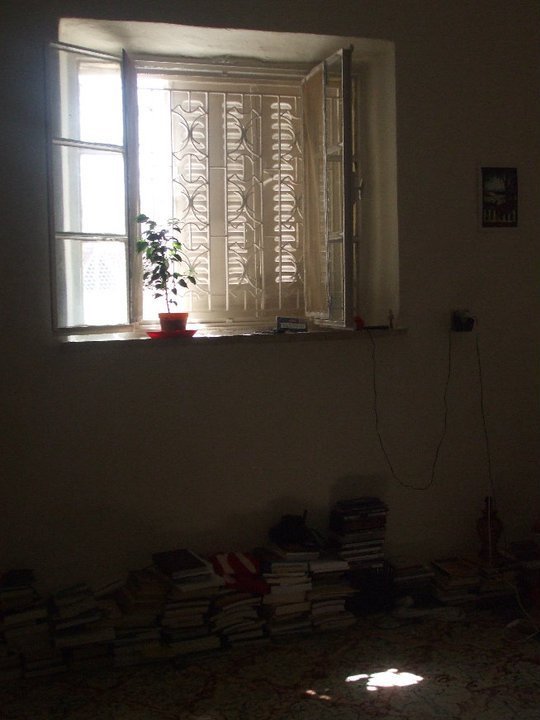

Some months after I left Palestine, S did too, which meant vacating the house we’d shared in Jerusalem. He told me later that he’d left it exactly the way it was, and so had our landlord, the kindly man who’d winked to let me know what he knew and make sure I could tell he didn’t mind. All the furniture, all the dishes, all the decorations: still there, intact. When I pause to remember it, years later, in the place and the vocation and the language that have become my entire life, I can instantly return to that apartment: the succulents on the sill, the space heater that seared my skirt, the mug from someone else’s mother, the hard white couch. Who knows how long they stayed right where they were, all these tender objects translated into a single place by the people who lived there, one little world in the world before someone else moved in and made it new.

Copyright © 2022 by Robin Myers. All rights reserved.