(A black-and-white drawing of a man in a hooded jacket reading a book.) Title: Tell Me Where to Go

(Panel 1: An insect-man eats at a table while kicking away a man with an axe. Panel 2: An insect-woman smiles at the insect-baby she's holding while pushing away a uniformed man with a gun. Panel 3: A newly married insect couple smiles at a photographer while the female member of the couple kicks away a man with a gun.) NARRATION: 2:1 The search for the Mirror is painful. Each time you are rejected ... You lose a bar on your life meter.

(Panel 1: A creature looks at a cell phone while holding up his other hand in front of a sweating person holding a knife. Panel 2: An insect-man looks at his phone while waving off a bewildered man standing behind him. Panel 3: A hooded man hangs his head.) NARRATION: The Mirror is foggy. You can't see anything. DIALOGUE: Nope. Nope. Nope. Nope! Nope! Nope! NARRATION: 2:2 The hardest war is the one the enemy doesn't even know is happening. A passionate, one-sided fight. An unrequited war. The search for the Mirror is one failure after another. Morale drops among the crew.

(Panel 1: Three armed men crouch behind a wall topped with barbed wire. One of them speaks on a walkie-talkie. Panel 2: An armed man throws a stick of dynamite while his companion holds a gun.) HOODED MAN: Recon team status report? WALKIE-TALKIE MAN: They're standing by. Launch operation? NARRATION: 2:3 You are an animal. You are not a plant. Stop trying to fix all your problems in the same place you were born. DYNAMITE MAN: Go! Throw the smoke bombs! NARRATION: The captain dispatches the recon team to the embassy of Country 49, but expectations are low. His only hope is that they make it out without any major injuries.

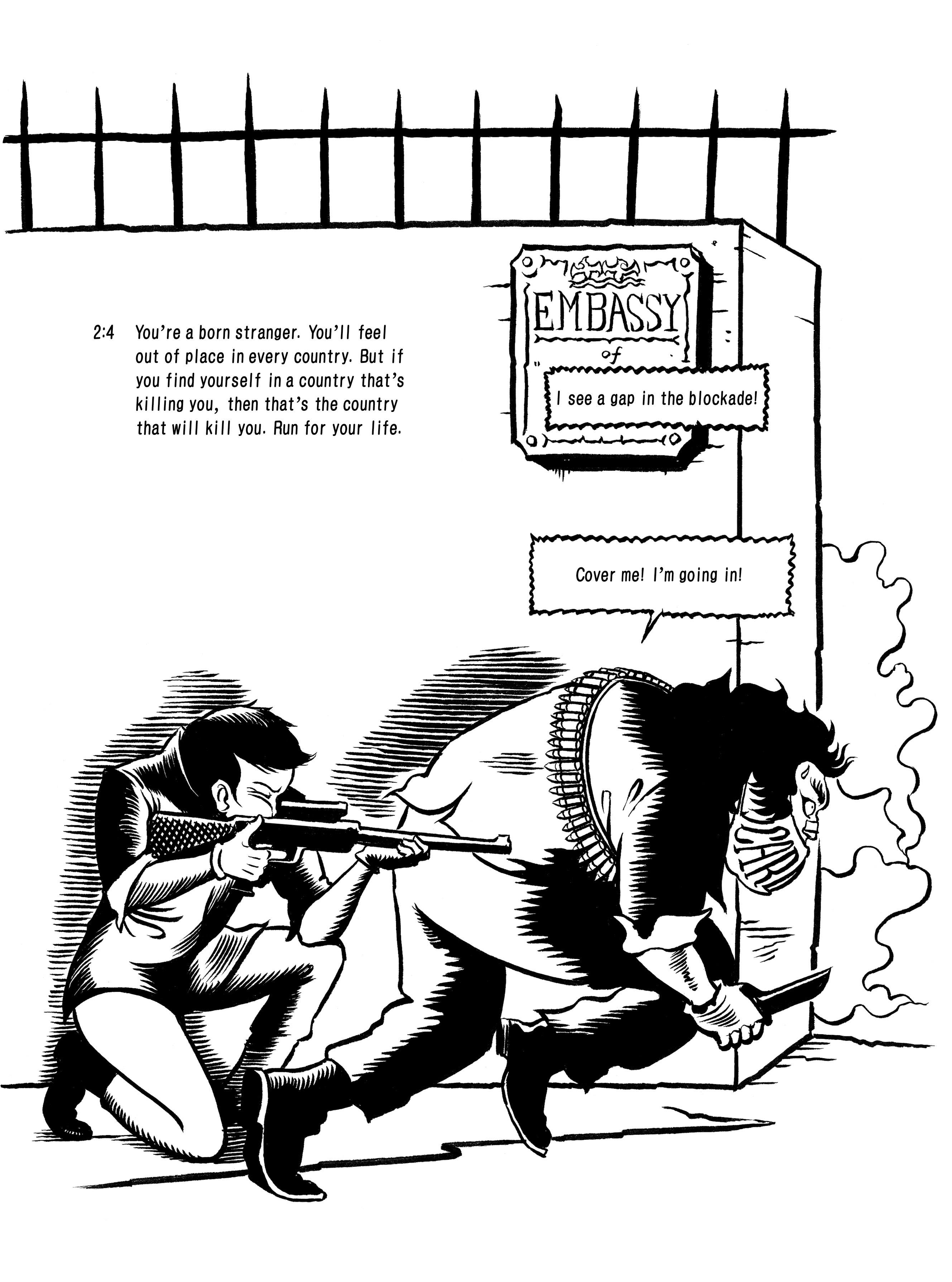

(A man with a knife and a woman with a gun crouch outside a wall marked "Embassy.") NARRATION: 2:4 You're a born stranger. You'll feel out of place in every country. But if you find yourself in a country that's killing you, then that's the country that will kill you. Run for your life. MAN: I see a gap in the blockade! Cover me! I'm going in!

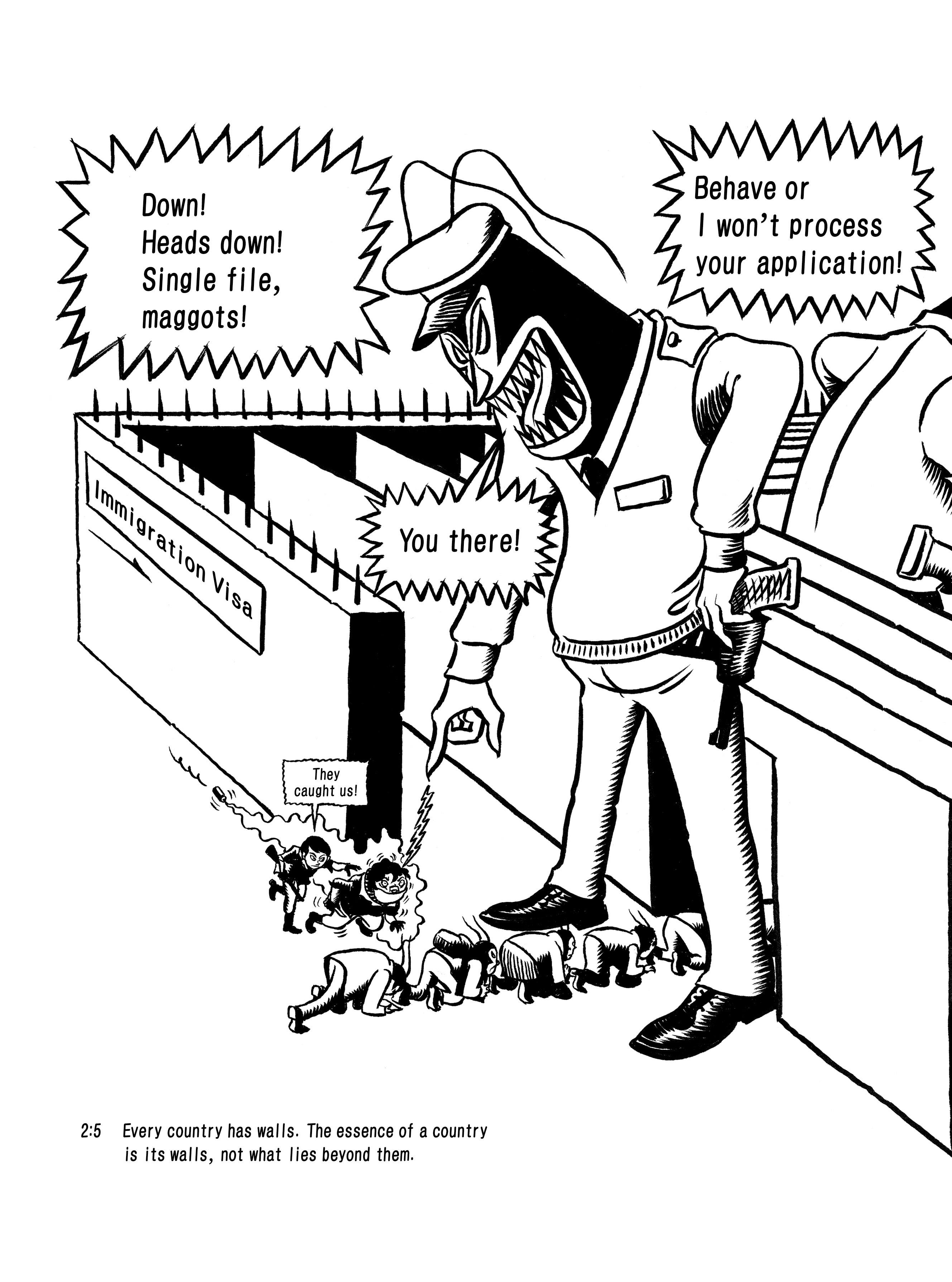

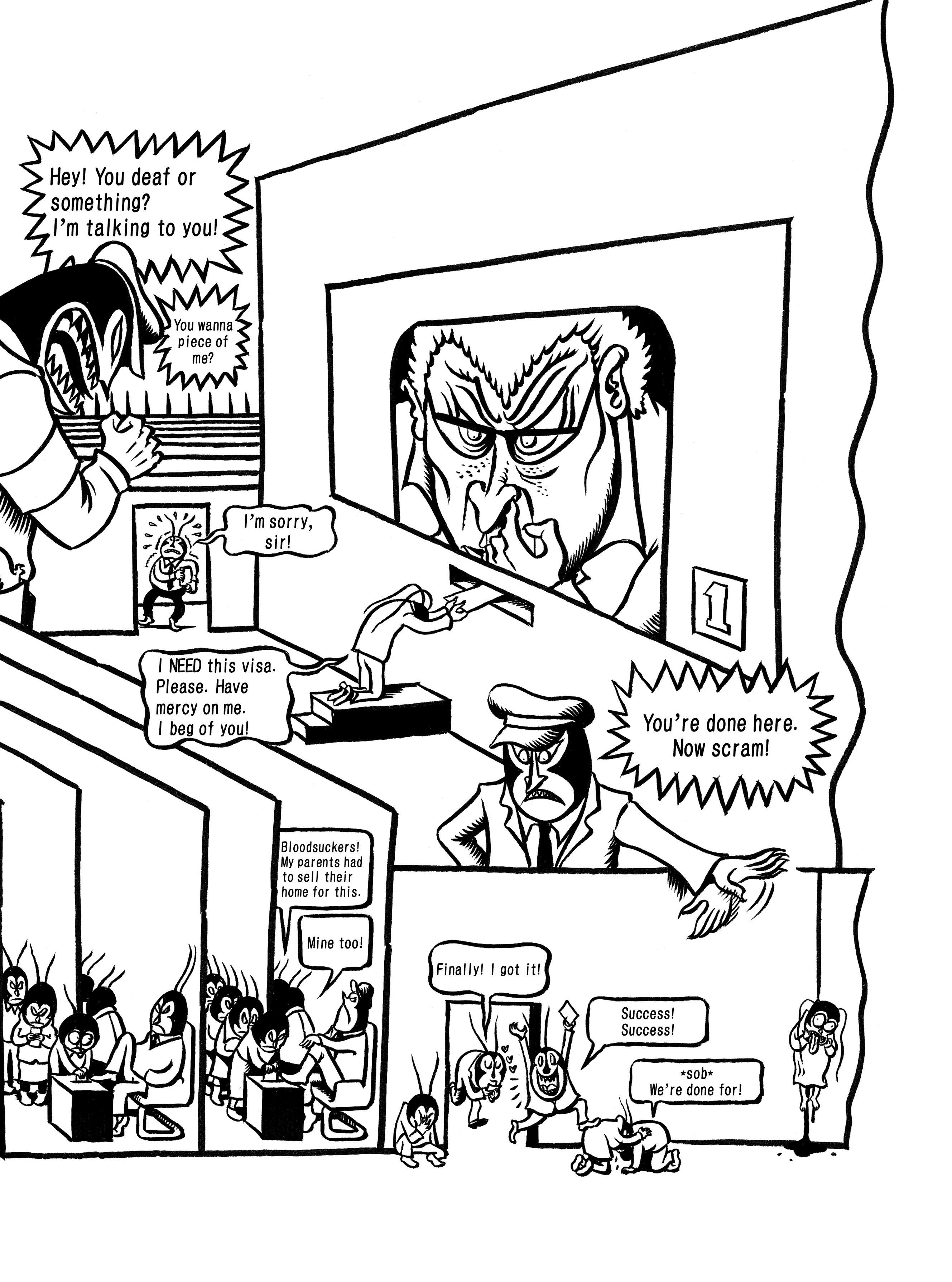

(Small cockroaches move through the visa maze as large cockroaches in uniform interrogate and yell at them. A few small cockroaches emerge at the end of the maze and celebrate their visas, while several others crouch on the ground crying.) LARGE COCKROACH 1: Hey! You deaf or something? I'm talking to you! You wanna piece of me? SMALL COCKROACH 1: I'm sorry, sir! SMALL COCKROACH 2: I NEED this visa. Please. Have mercy on me. I beg of you! SMALL COCKROACH 3: Bloodsuckers! My parents had to sell their home for this. SMALL COCKROACH 4: Mine too! LARGE COCKROACH 2: You're done here. Now scram! SMALL COCKROACH 5: Finally! I got it! SMALL COCKROACH 6: Success! Success! SMALL COCKROACH 7: *sob* We're done for!

(Small cockroaches move through the visa maze as large cockroaches in uniform interrogate and yell at them. A few small cockroaches emerge at the end of the maze and celebrate their visas, while several others crouch on the ground crying.) LARGE COCKROACH 1: Hey! You deaf or something? I'm talking to you! You wanna piece of me? SMALL COCKROACH 1: I'm sorry, sir! SMALL COCKROACH 2: I NEED this visa. Please. Have mercy on me. I beg of you! SMALL COCKROACH 3: Bloodsuckers! My parents had to sell their home for this. SMALL COCKROACH 4: Mine too! LARGE COCKROACH 2: You're done here. Now scram! SMALL COCKROACH 5: Finally! I got it! SMALL COCKROACH 6: Success! Success! SMALL COCKROACH 7: *sob* We're done for!

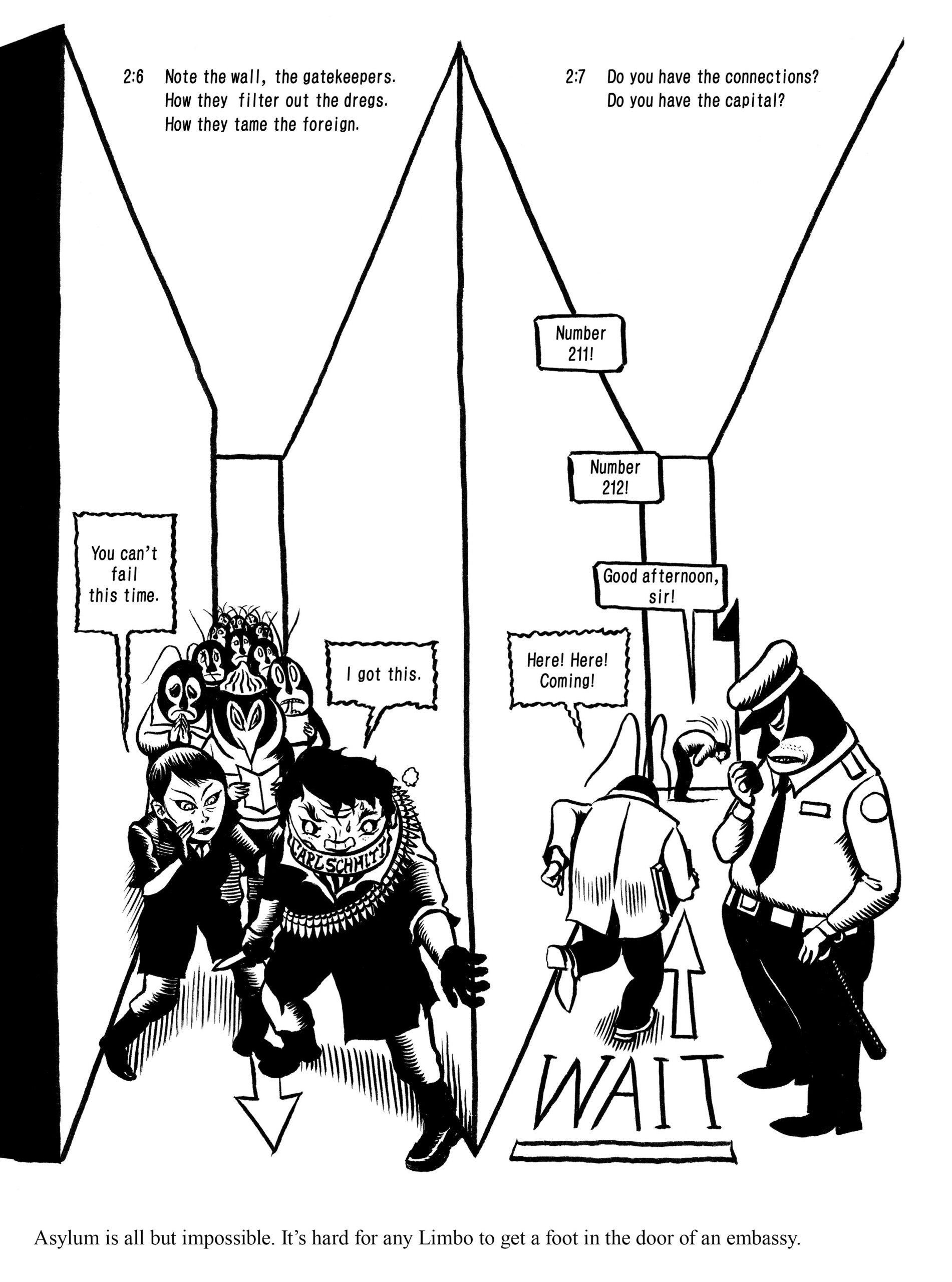

(The man and the woman stand in a packed hallway full of cockroaches. A cockroach guard waits around the corner.) NARRATION: 2:6 Note the wall, the gatekeepers. How they filter out the dregs. How they tame the foreign. WOMAN: You can't fail this time. MAN: I got this. NARRATION: 2:7 Do you have the connections? Do you have the capital? GUARD: Number 211! Number 212! SMALL COCKROACH 1: Good afternoon, sir! SMALL COCKROACH 2: Here! Here! Coming! NARRATION: Asylum is all but impossible. It's hard for any Limbo to get a foot in the door of an embassy.

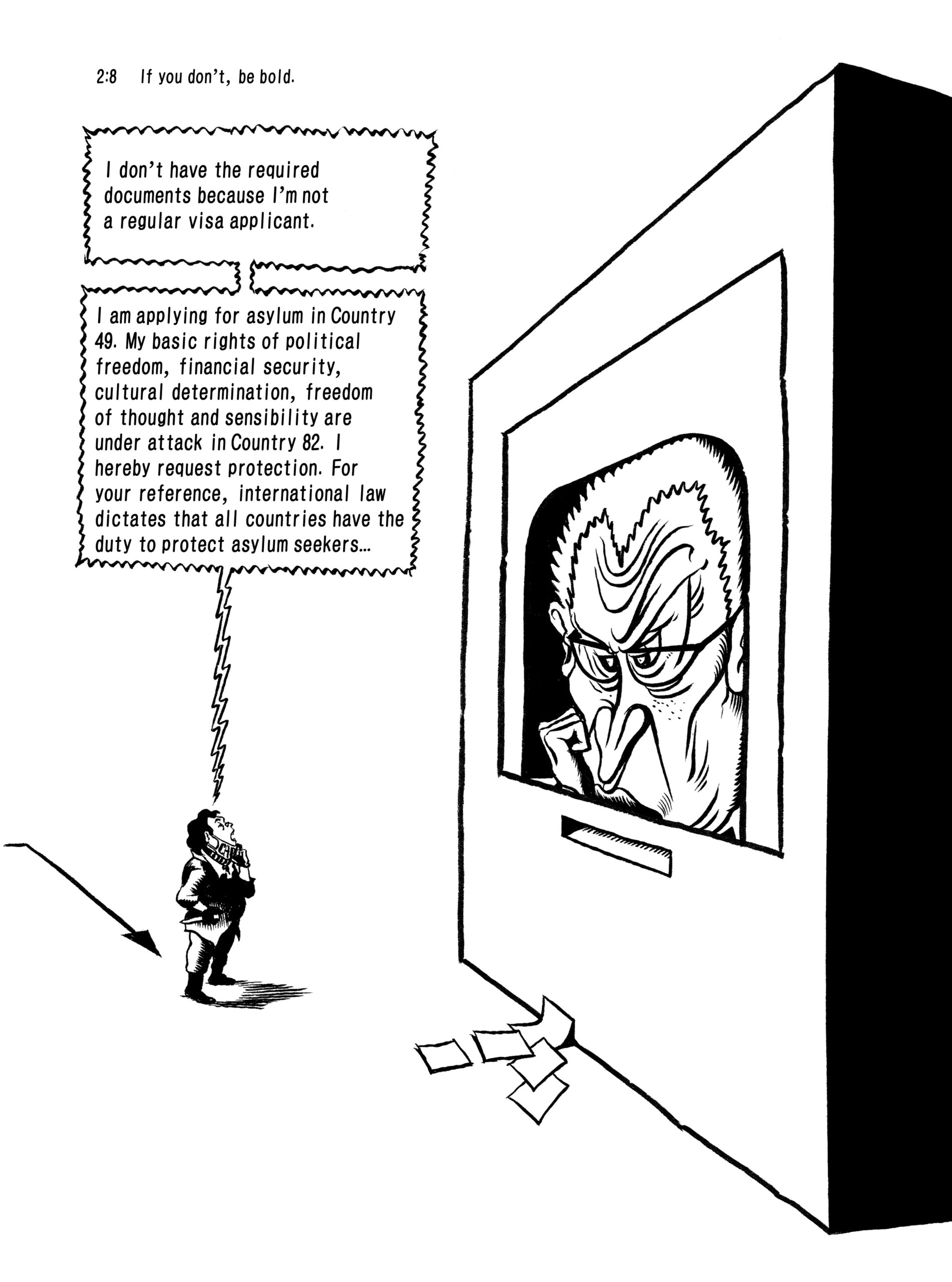

(The man from the previous panel stands before an enormous bureaucrat at a desk.) NARRATION: 2.8 If you don't, be bold. MAN: I don't have the required documents because I'm not a regular visa applicant. I am applying for asylum in Country 49. My basic rights of political freedom, financial security, cultural determination, freedom of thought and sensibility are under attack in Country 82. I hereby request protection. For your reference, international law dictates that all countries have the duty to protect asylum seekers...

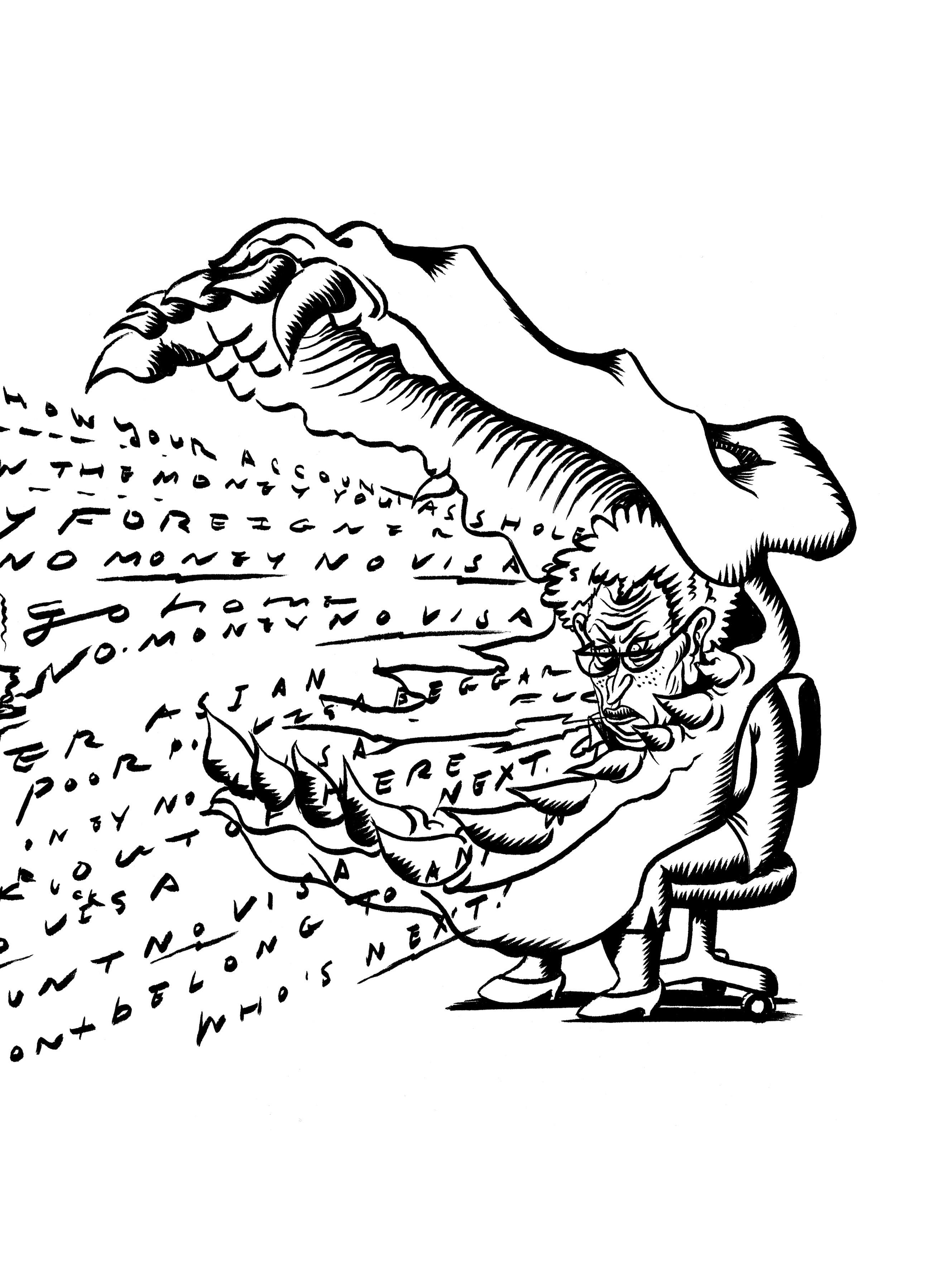

(The man disappears into a mass of barely legible words.)

(The bureaucrat, wearing the jaws of an enormous animal over his head, is the source of the mass of words enveloping the man in the previous panel.)

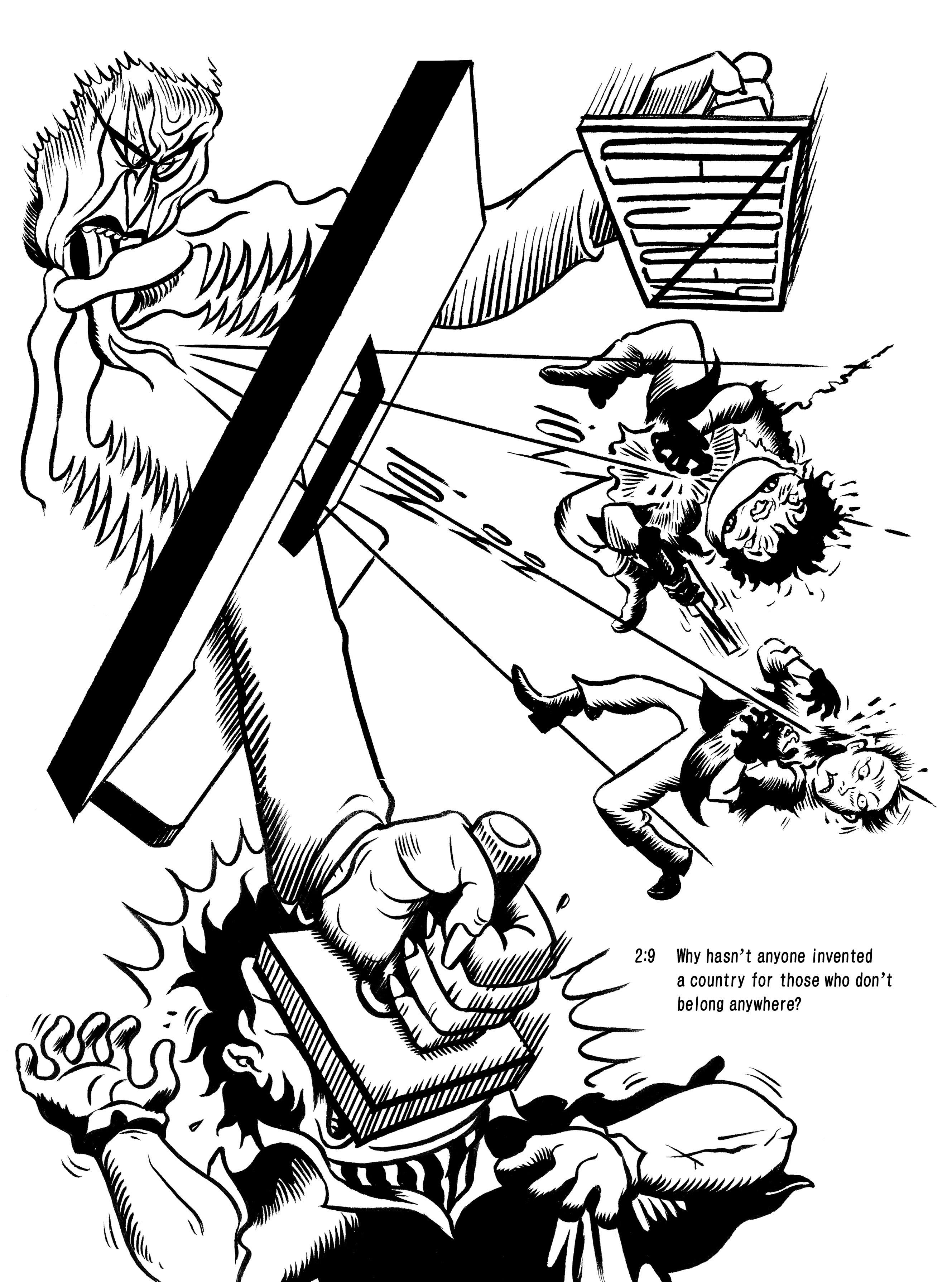

(The enormous bureaucrat sends the man and woman flying out the door and stamps them with a huge "Rejected" stamp.) NARRATION: 2:9 Why hasn't anyone invented a country for those who don't belong anywhere?

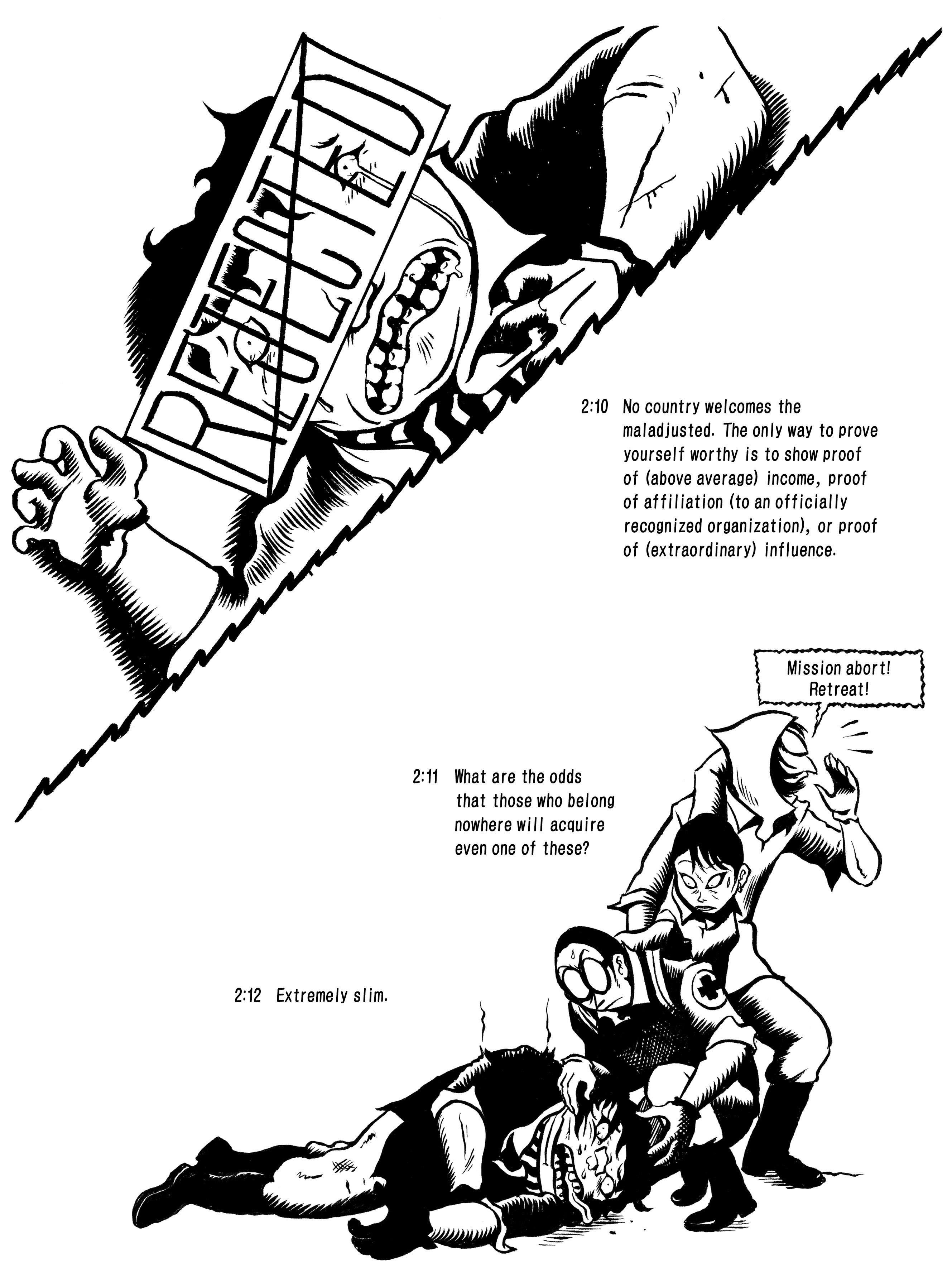

(Panel 1: The man's face has been squashed by the stamp and now reads "Rejected." Panel 2: Three of the man's renegade comrades crowd around him.) NARRATION: 2:10 No country welcomes the maladjusted. The only way to prove yourself worthy is to show proof of (above average) income, proof of affiliation (to an officially recognized organization), or proof of (extraordinary) influence. HOODED MAN: Mission abort! Retreat! NARRATION: 2:11 What are the odds that those who belong nowhere will acquire even one of these? NARRATION: 2:12 Extremely slim.

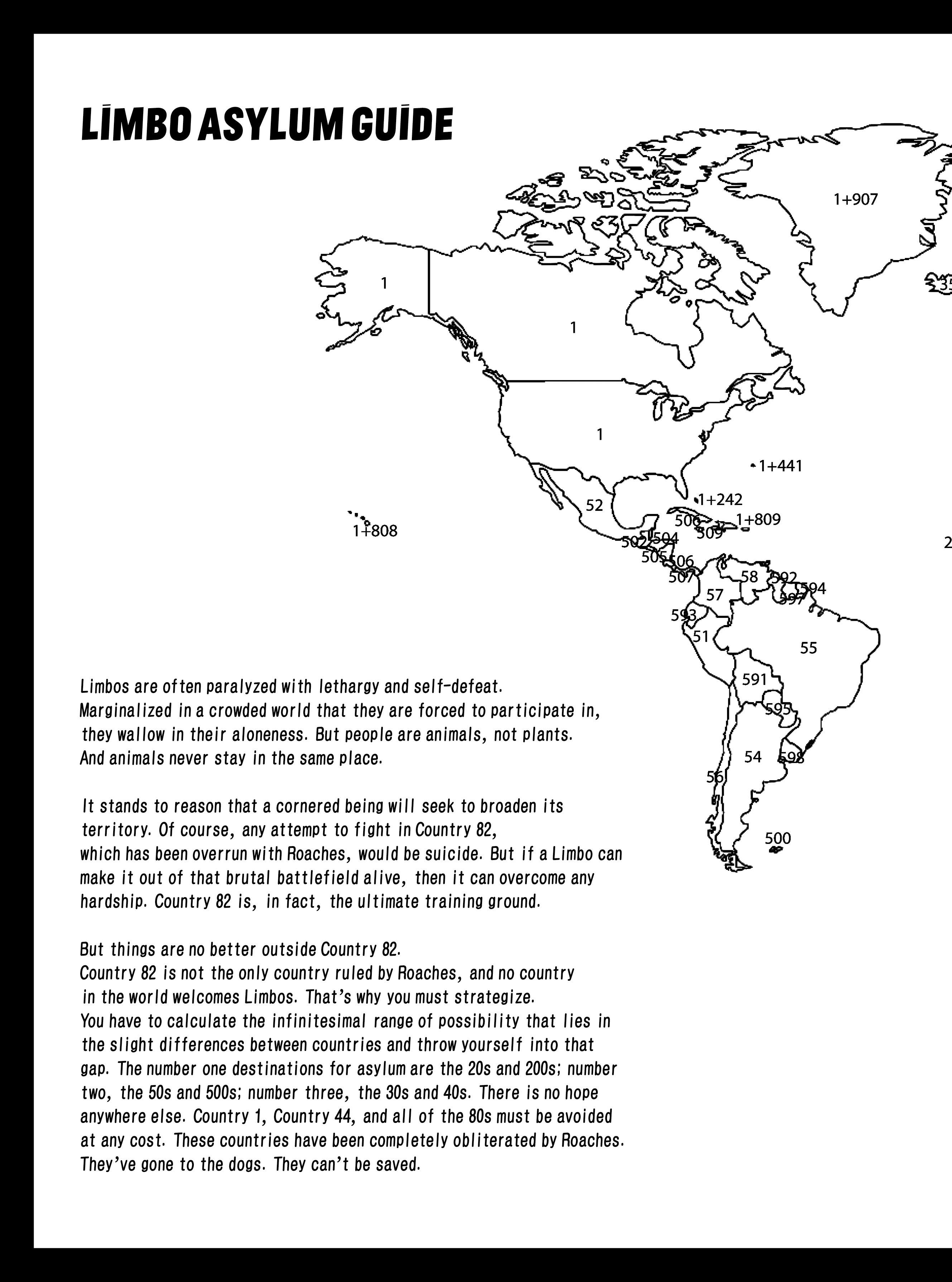

(A black-and-white map of the Western Hemisphere. Each country is numbered.) LIMBO ASYLUM GUIDE *Limbos are often paralyzed with lethargy and self-defeat. Marginalized in a crowded world that they are forced to participate in, they wallow in their aloneness. But people are animals, not plants. And animals never stay in the same place. *It stands to reason that a cornered being will seek to broaden its territory. Of course, any attempt to fight in Country 82, which has been overrun with Roaches, would be suicide. But if a Limbo can make it out of that brutal battlefield alive, then it can overcome any hardship. Country 82 is, in fact, the ultimate training ground. *But things are no better outside Country 82. Country 82 is not the only country ruled by Roaches, and no country in the world welcomes Limbos. That's why you must strategize. You have to calculate the infinitesimal range of possibility that lies in the slight differences between countries and throw yourself into that gap. The number one destinations for asylum are the 20s and 200s; number two, the 50s and 500s; number three, the 30s and 40s. There is no hope anywhere else. Country 1, Country 44, and all of the 80s must be avoided at any cost. These countries have been completely obliterated by Roaches. They've gone to the dogs. They can't be saved.

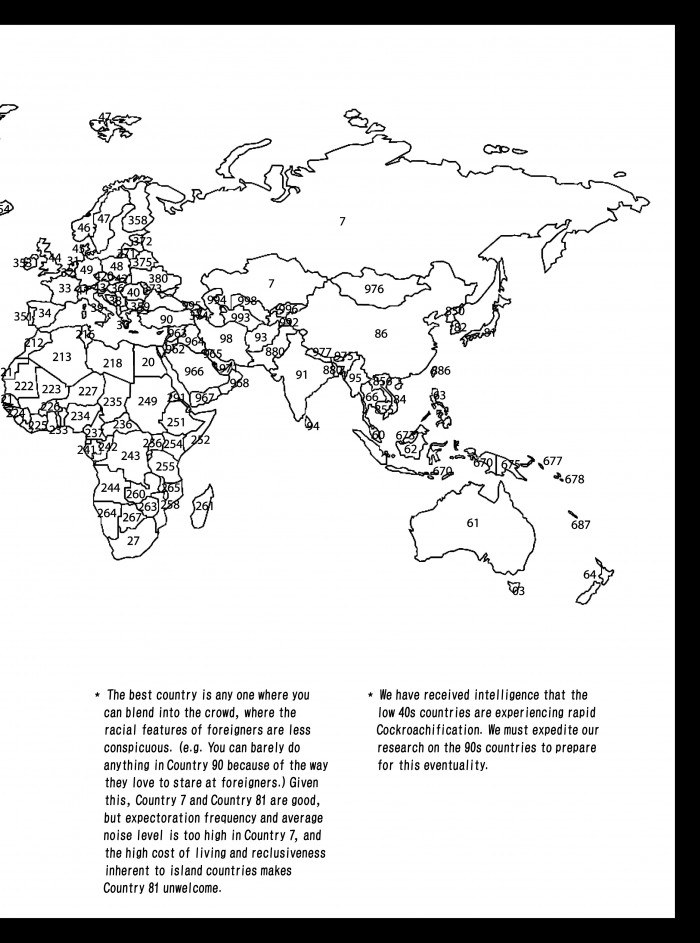

(A black-and-white map of the Eastern Hemisphere. Each country is numbered.) *The best country is any one where you can blend into the crowd, where the racial features of foreigners are less conspicuous. (e.g. You can barely do anything in Country 90 because of the way they love to stare at foreigners.) Given this, Country 7 and Country 81 are good, but expectoration frequency and average noise level is too high in Country 7, and the high cost of living and reclusiveness inherent to island countries makes Country 81 unwelcome. *We have received intelligence that the low 40s countries are experiencing rapid Cockroachification. We must expedite our research on the 90s countries to prepare for this eventuality.