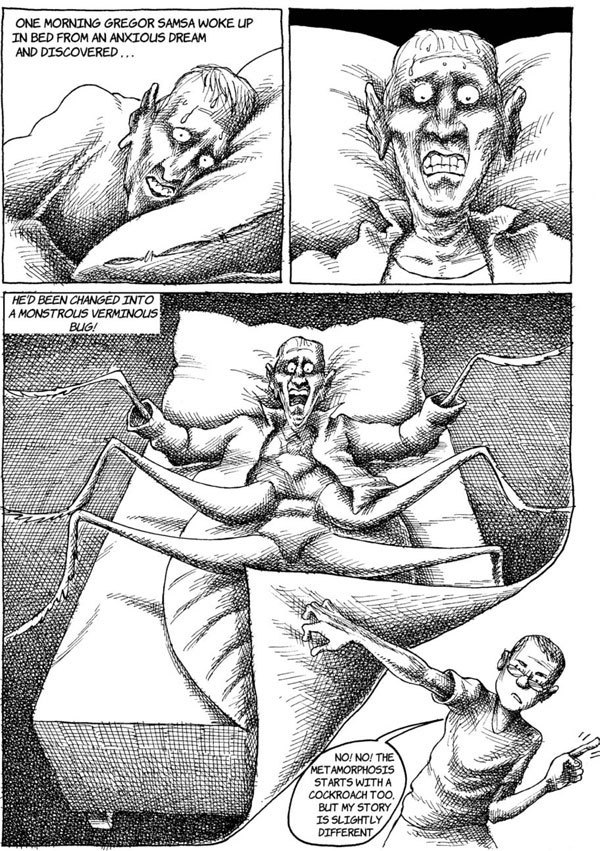

[One morning Gregor Samsa woke up from an anxious dream and discovered...] [He'd been changed into a monstrous verminous bug!] Mana: No! No! The metamorphosis starts with a cockroach too. But my story is slightly different.

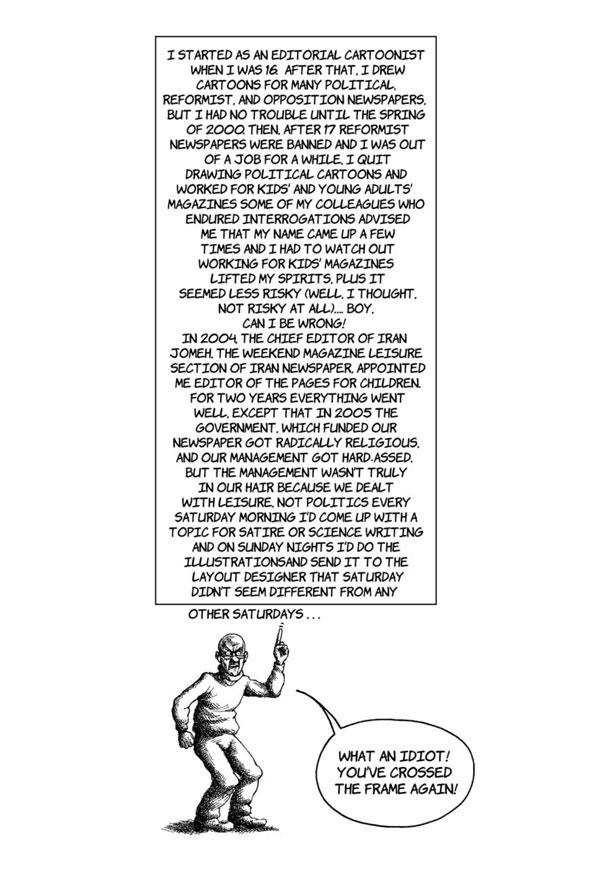

[I started as an editorial cartoonist when I was 16. After that, I drew cartoons for many political, reformist, and opposition newspapers but I had no trouble until the spring of 2000. Then, after 17 reformist newspapers were banned and I was out of a job for a while, I quit drawing political cartoons and worked for kid's and young adult's magazines. Some of my colleagues who endured interrogations advised me that my name came up a few times and I had to watch out. Working for kid's magazines lifted my spirits, plus it seemed less risky (well, I thought not risky at all...) Boy! Can I be Wrong! In 2004, the chief editor of Iran Jomeh, the weekend magazine leisure section of Iran newspaper, appointed me editor of the pages for children. For two years, everything went well except that in 2005 the government, which funded our newspaper, got radically religious. And our management got hard assed. But the management wasn't truly in our hair because we dealt with leisure not politics. Every Saturday morning I'd come up with a topic for satire or science writing and on Sunday nights I'd do the illustrations and send it to the layout designer. That Saturday didn't seem different from any other Saturday...] -What an idiot! You've crossed the frame again!

[I was thinking about what shit I should afflict my 10-year-old cartoon character, Soheil, with. It was May and Tehran had started to get warm...] Soheil: Admit it! You run our of ideas! Mana: You wish! I'll get you in big trouble this time! Just wait. Soheil: What are you drawing? It's not a...

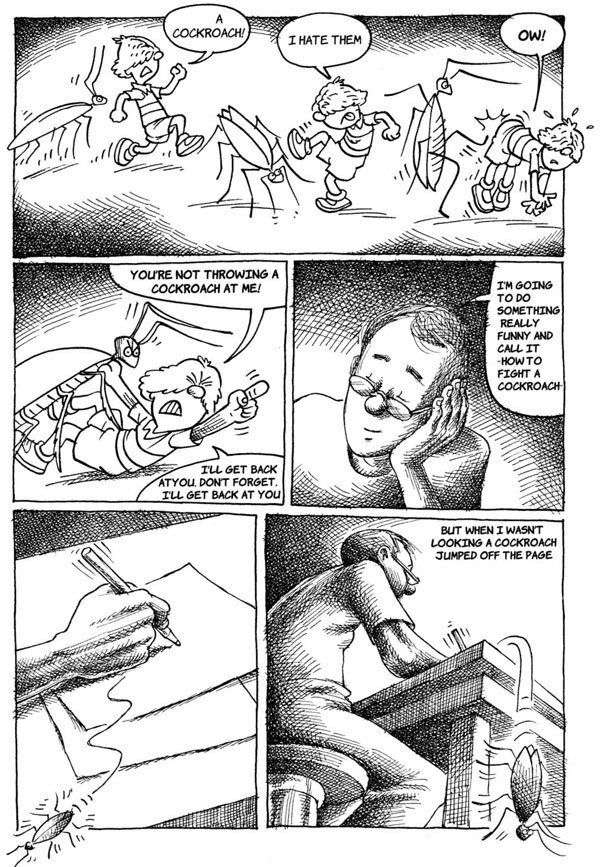

Soheil: A cockroach! I hate them! Ow! You are not throwing a cockroach at me! I'll get back at you. Don't forget. I'll get back at you. Mana: I'm going to do something really funny and call it how to fight a cockroach. [But when I wasn't looking a cockroach jumped off the page.]

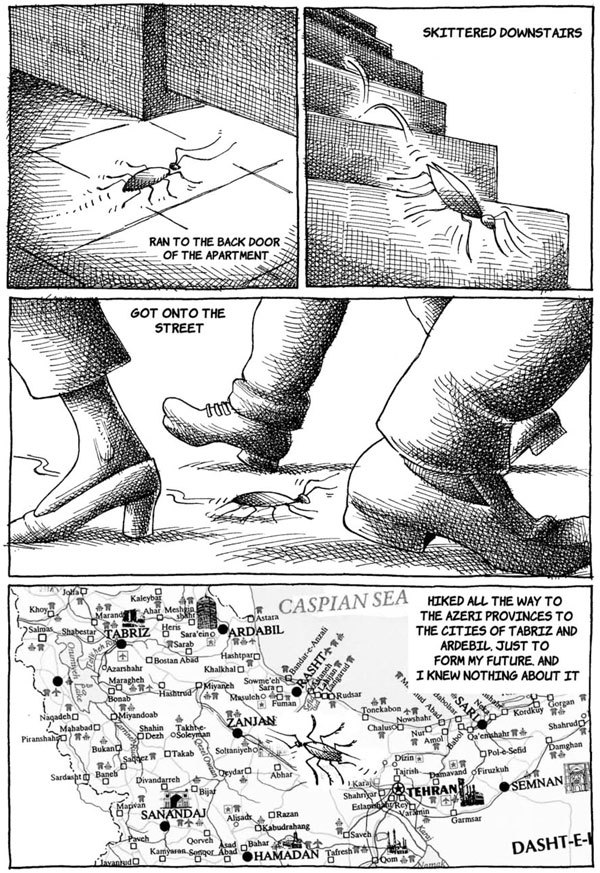

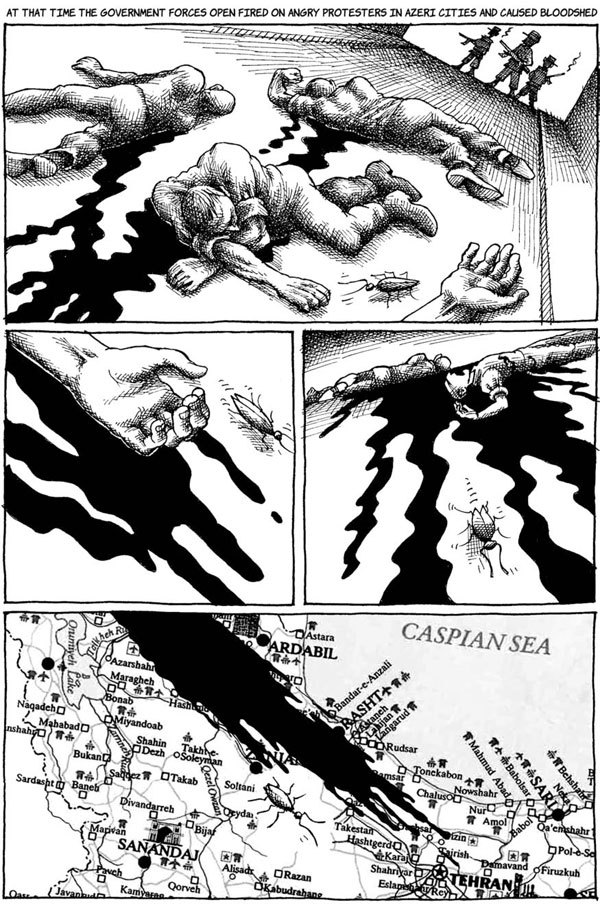

[Ran to the backdoor of the apartment. Skittered downstairs. Got onto the street. Hiked all the way to the Azarbayjan provinces to the cities of Tabriz and Ardabil. Just to form my future, and I knew nothing about it.]

[A good week was passed from the date that issue was published. I kissed Mansoureh goodbye I put my week's work on a CD and ran to Iran Jomeh's office...was feeling great At the office Mehrdad, the editor, called me] Mehrdad: Mana! Before you go to the layout room I want a word with you! Mana: Sure!

Mehrdad: A couple of Azeri parents called and complained about the cockroach thing. I didn't pay close attention, but we have to watch out for ethnic sensitivities, you know. Mana: Ethnic sensitivities?! Mehrdad: Oh yes. In one of the cartoons a cockroach tosses out an Azeri word. Mana: You can't mean the namana! Are you kidding me? I often myself use the term whenever I can't get something I say. Namana? Mehrdad: I know. It happens. Just be aware of it from now on.

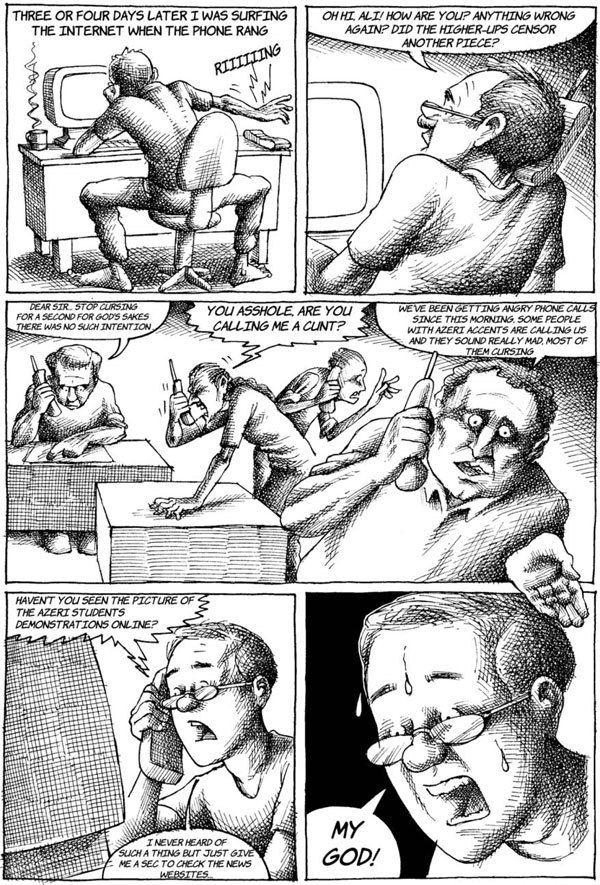

[Three or four days later I was surfing the internet when the phone rang.] Mana: Oh Hi Ali! How are you? Anything wrong again? Did the higher-ups censor another piece? -Dear Sir! Stop cursing for a second for God's sake. There was no such intention! - You asshole! Are you calling me a cunt? Ali:We've been getting angry phone calls since this morning. Some people with Azeri accents are calling us and they soud really mad, most of them cursing. Haven't you seen the pictures of Azeri students' demonstrations online? Mana: I've never heard of such a thing but just give me a sec to check the news websites. My God!

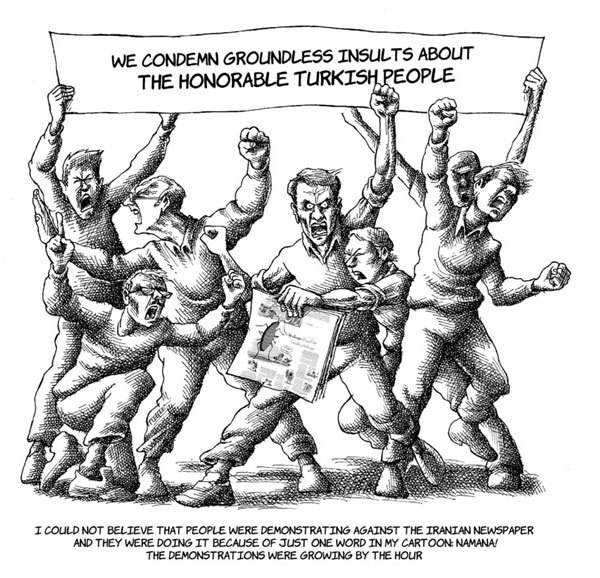

Crowds: We condemn groundless insults about the honorable Turkish people. [I could not believe that people were demonstrating against the Iranian newspaper and they were doing it because of just one word in my cartoon: Namana! The demonstrations were growing by the hour.]

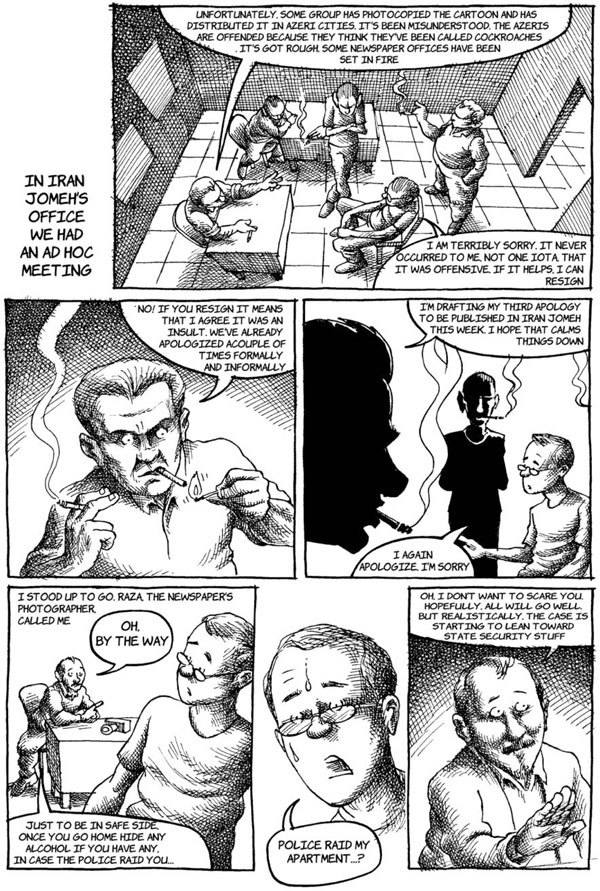

[In Iran Jomeh's office we had an ad hoc meeting.] -Unfortunately some group has photocopied the cartoon and has distributed it in Azeri cities. It's been misunderstood. The Azeris are offended because they think they have been called cockroaches. It's got rough. Some newspaper offices have been set in fire. Mana: I'm terribly sorry. It never occurred to me that it was offensive. If it helps I can resign. - No if you resign it means that I agree it was an insult. We've already apologized a couple of times formally and informally. - I'm drafting my third apology to be published in Iran Jomeh this week. I hope that calms things down. Mana: I again apologize. I'm sorry. [I stood up to go. Reza, the magazine's photographer called me] Reza: Oh by the way. Just to be on the safe side, once you go home hide any alcohol if you have any. In case the police raid you... Mana: Police raid my apartment...? Reza: Oh I don't want to scare you. Hopefully, all will go well, but realistically, the case is starting to lean toward state security stuff.

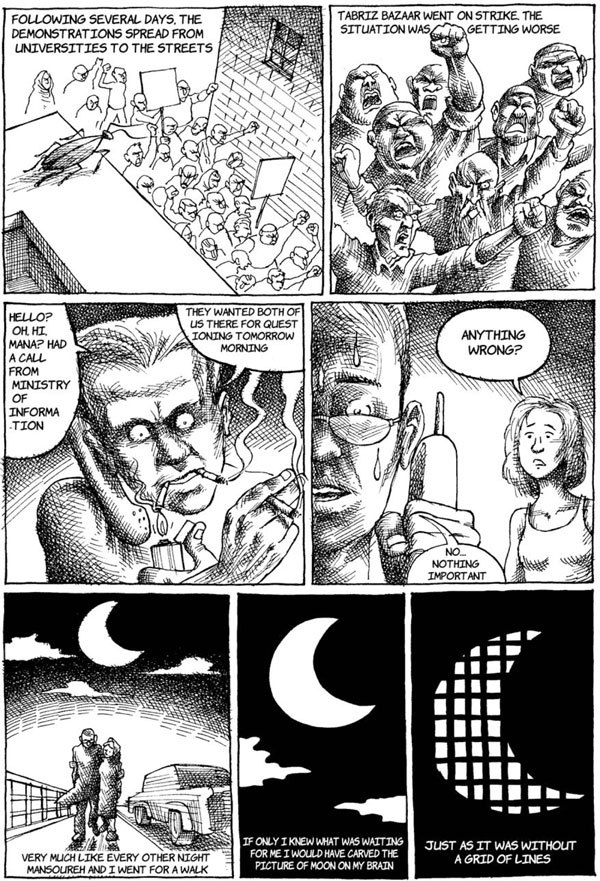

[Following several days, the demonstrations spread from universities to the streets. Tabriz Bazaar got on strike. The situation was getting worse.] -Hello? Oh, Hi, Mana? Had a call from the ministry of information. They wanted both of us there for questioning in the morning. Mansoureh: Anything wrong? Mana: No...Nothing important. [Very much like any other night Mansoureh and I went for a walk. If only I knew what was waiting for me I would have carved the picture of moon on my brain. Just as it was without a grid of lines.]

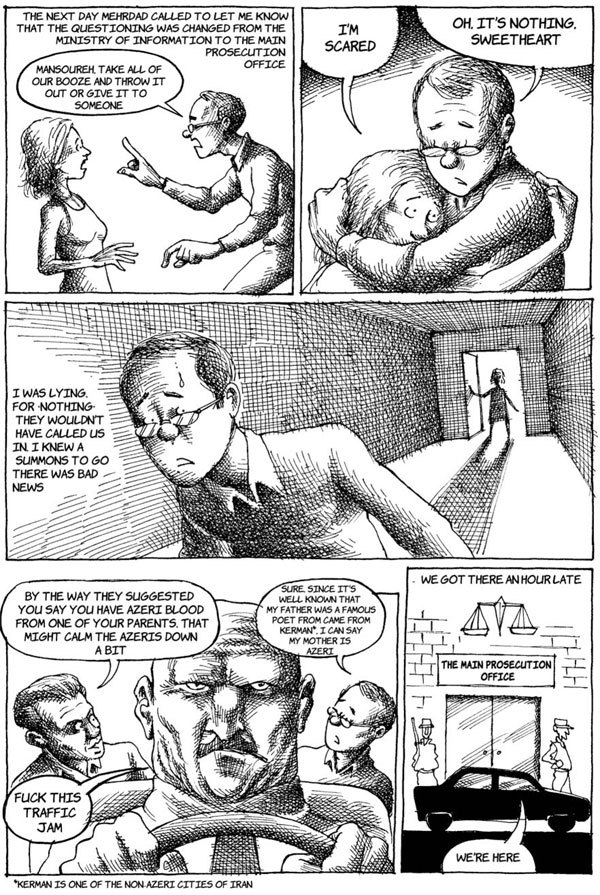

[The next day Mehrdad called to let me know that the questioning was changed from the ministry of information to the main prosecution office.] Mana: Mansoureh! Take all of our booze and throw it out or give it to someone. Mansoureh: I'm scared! Mana: Oh It's nothing sweetheart. [I was lying. For nothing they wouldn't have called us in. I knew a summons to go there was bad news.] Mehrdad: By the way they suggested you say you have Azeri blood from one of your parents. That might calm the Azeris down a bit. Mana: Sure. Since it is well known that my father was a famous poem from Kerman I can say my mother is Azeri. Mehrdad: Fuck this traffic jam. [We arrived there an hour late.] - We are here.

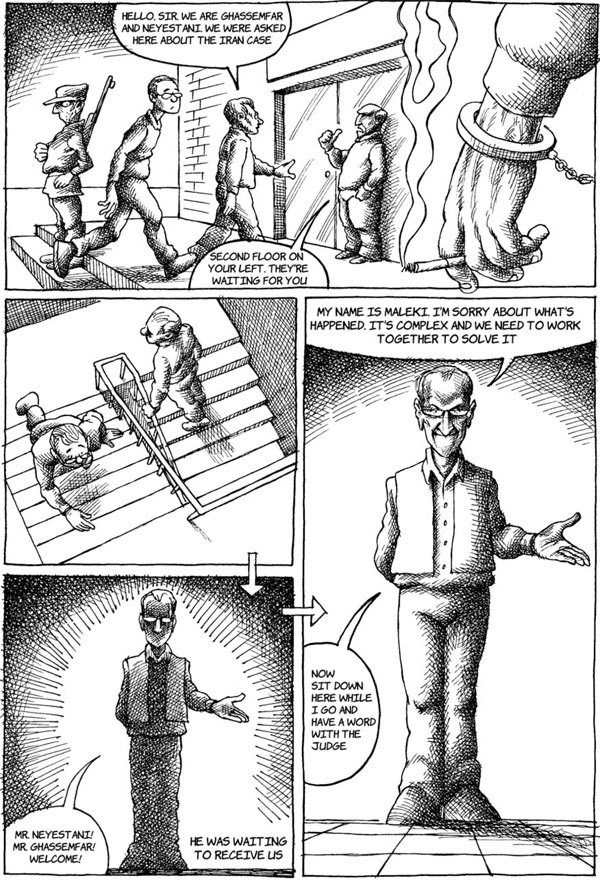

Mehrdad: Hello Sir. We are Ghasemfar and Neyestani. We were asked here about the Iran case. - Second floor on your left. They are waiting for you. - Mr. Neyestani! Mr. Ghasemfar! Welcome. [He was waiting to receive us.] -My name is Maleki. I'm sorry about what's happened. It's complex and we need to work together to solve it. Now sit down here while I go to have a word with the judge.

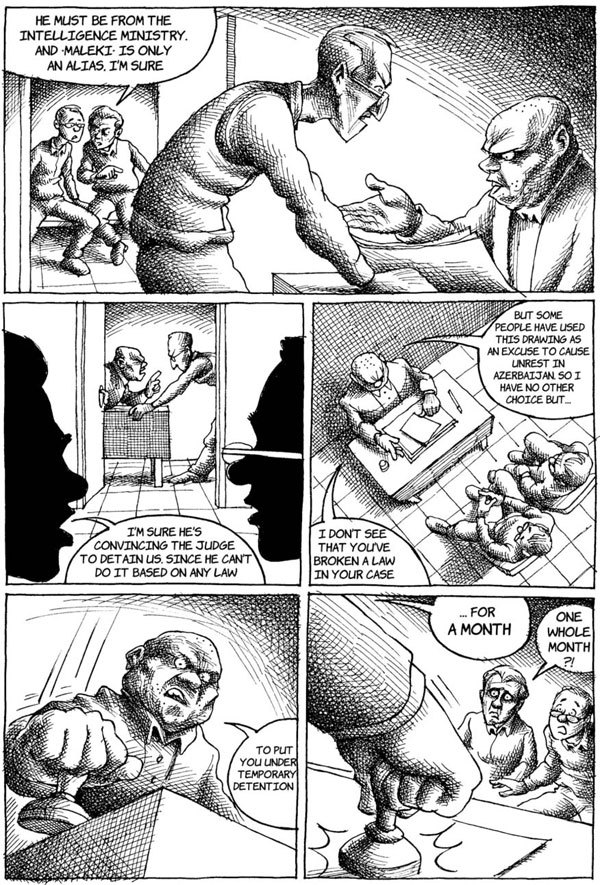

Mehrdad: He must be from the Intelligence ministry and 'Maleki' is only an alias, I'm sure. I'm sure he is convincing the judge to detain us since he can't do it based on any law. Judge: I don't see that you've broken any law in your case. But some people have used this drawing as an excuse to cause unrest in Azerbaijan. So I have no other choice but...to put you under temporary detention...for a month. Mehrdad: One whole month?

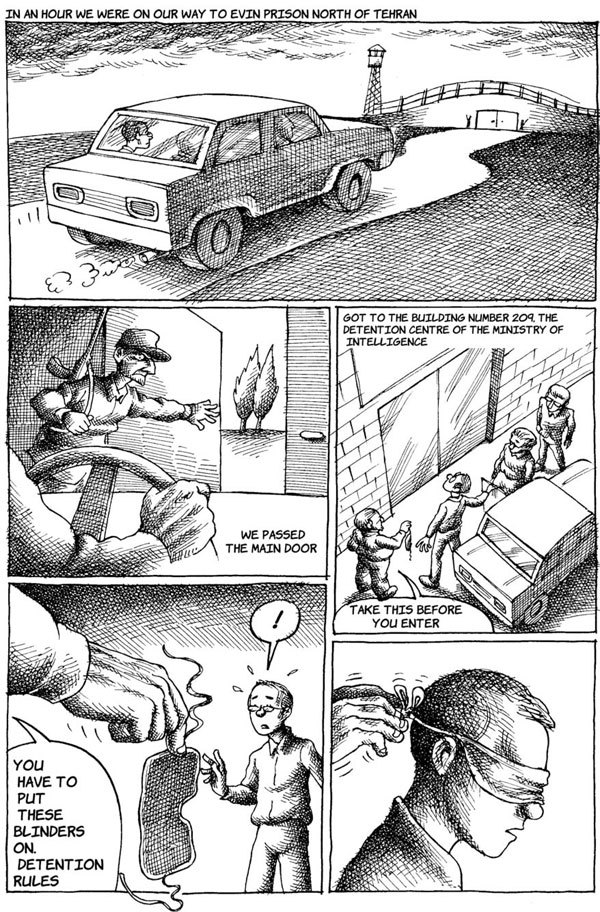

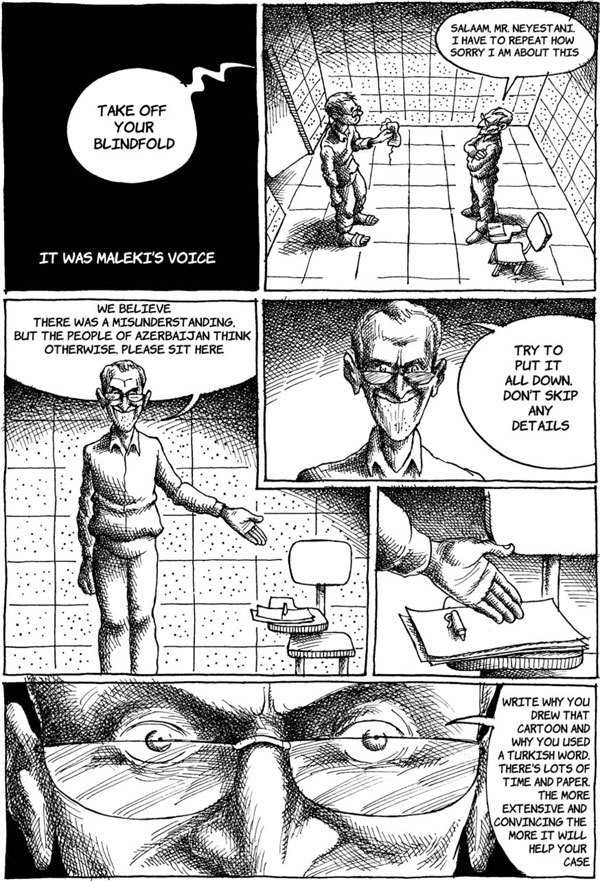

[We passed the main door. Got to the building 209: the detention center of the ministry of Intelligence.] -take this before you enter! You have to put these blinders on. detention rules! Mana: !

- Take off your blindfold. [It was Maleki's voice.] Maleki: Salam, Mr. Neyestani. I have to repeat how sorry I am about this. We believe there was a misunderstanding. But the people of Azerbaijan think otherwise. Please sit here. Put it all down. Don't skip any details. Write why you drew that cartoon and why you used a Turkish word. There is lots of time and paper. The more extensive and convincing the more It will help your case.

Maleki(reading): And since summer was approaching and the weather was getting warmer and our house was full of cockroaches, I decided to make cockroaches the theme for that issue of the kids' magazine...the word 'namana' is always used in Farsi. I didn't have its Turkish roots in mind. Maleki: your answer isn't convincing Mr. Neyestani. Mana: Not my fault if reality isn't convincing. Maleki: Mr. Neyestani! Don't forget we are not against you. But the Turkish people of Azarbaijan are. They believe that whole thing was designed to humiliate Turks and their culture. They won't accept any other explanation. We'll continue our conversation tomorrow. Do try to find more solid reasons. You can take the pen and the papers with you. You are also allowed to keep your glasses. Mana: What do I have to write in my cell? Maleki: Write about the Iranian cartoonists that you know. Write anything you know about them. This is a unique chance for us to explore your information and complete your records.

[I had to write whatever I knew about my fellow cartoonists. But not being a social person I fortunately knew next to nothing about any of them, so I decided to fill the pages with some gossip, or even words about the quality of their cartoons] Mana (writing): For instance Mr. SH is a good example. Since his hands shake severely so now shaky lines are his style...Or Mr. M who is a paranoid type who knows nothing about drawing and sketching but thinks he is a big shot. Also, most of the times he picks his nose in public. [The fact that I didn't write anything important about people made me feel I wasn't a traitor.]

[At that time government forces open fired on angry protesters in Azeri cities and caused bloodshed.]

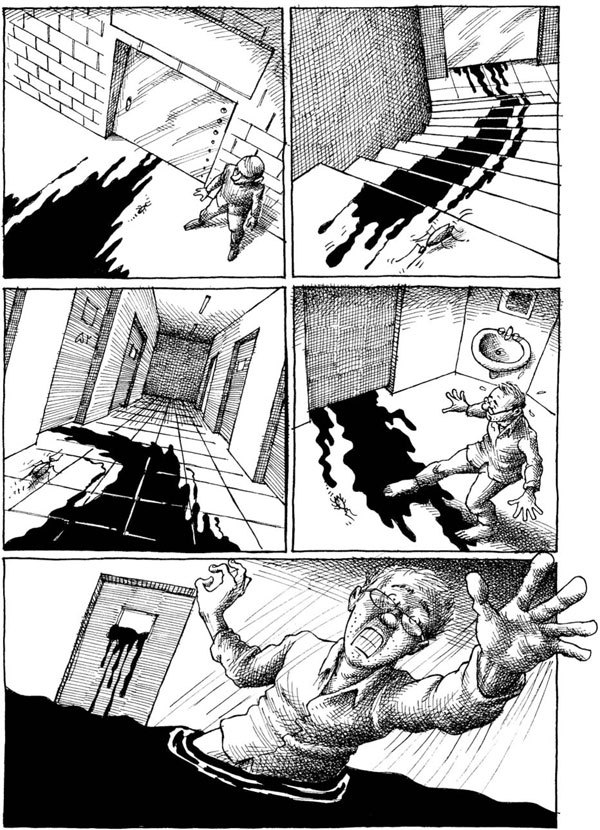

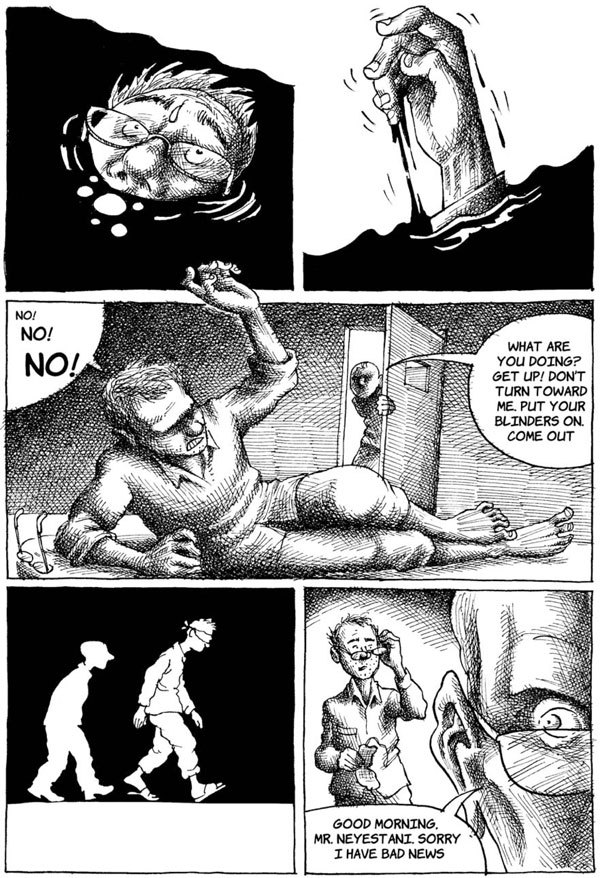

Mana(having a nightmare): No! No! No! - What are you doing? get up! Don't turn toward me. put your blinders on. come out. Maleki: Good morning Mr. Heyestani. Sorry I have bad news.

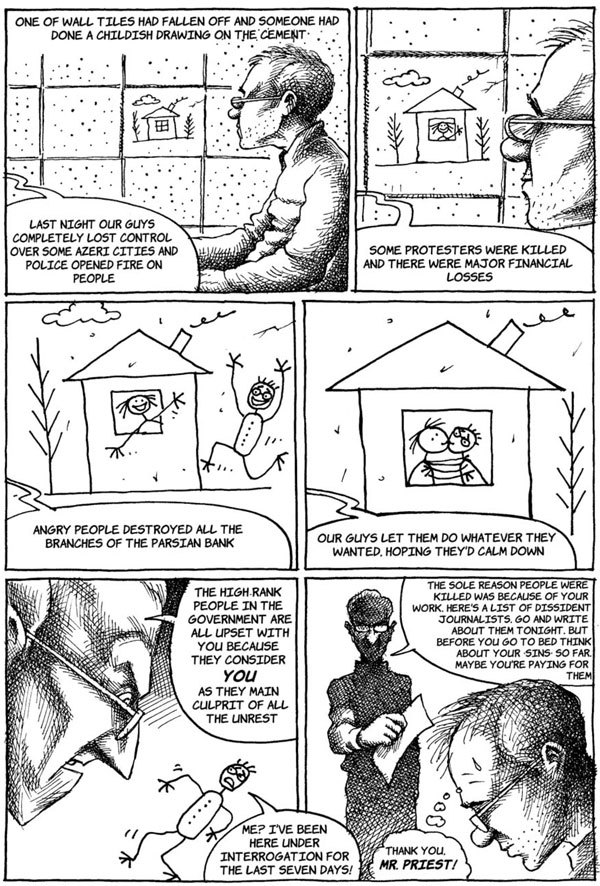

One of the wall tiles had fallen off and someone had done a childish drawing on the wall.] Maleki: Last night our guys completely lost control over some Azeri cities and police opened fire on people. Some protesters were killed and there were major financial losses. Angry people destroyed all the branches of the Persian Bank. Our guys let them do whatever they wanted hoping they would calm down. The high rank people in the government are all upset with you because they consider you as the main culprit of all the unrest. Mana: Me?! I've been here under interrogation for the last seven days! Maleki: The sole reason people were killed was because of your work. Here's a list of dissident journalists.

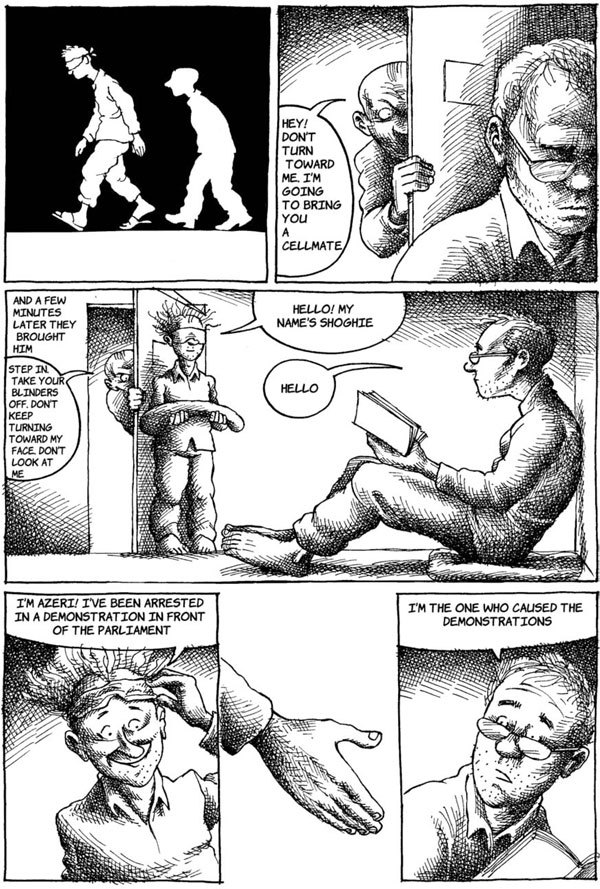

Maleki: Hey! Don't turn toward me. I'm going to bring you a cellmate.

[And a few minutes later they brought him]

Maleki: Step in. Take your blinders off. Don't keep turning toward my face. Don't look at me.

Shoghie: Hello! My name's Shoghie

Mana: Hello

Shoghie: I'm Azeri! I've been arrested in a demonstration in front of the parliament

Mana: I'm the one who caused the demonstrations

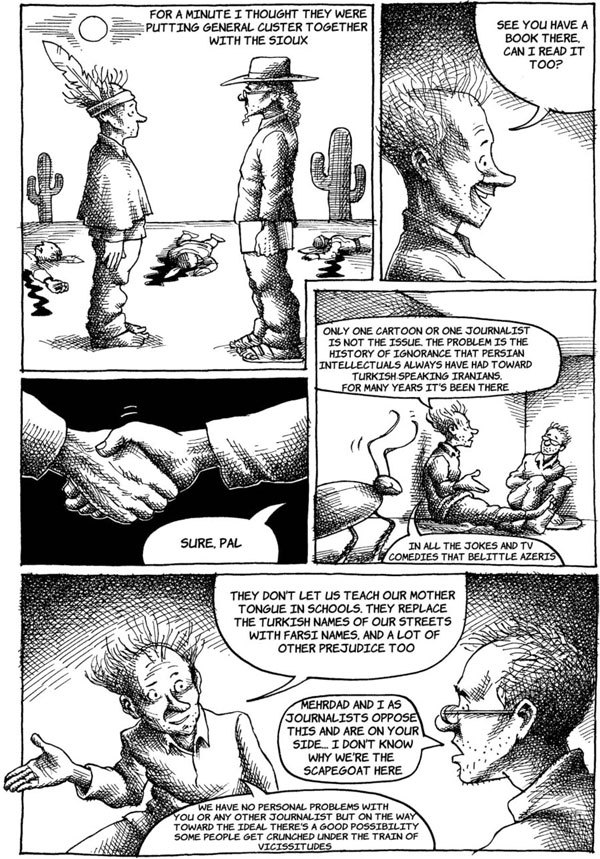

[For a minute I thought they were putting General Custer with the Sioux]

Shoghie: See you have a book there. Can I read it, too?

Mana: Sure, pal.

Shoghie: Only one cartoon or one journalist is not the issue. The problem is the history of ignorance that Persian intellectuals always have had toward Turkish speaking Iranians. For many years it's been there...

Shoghie: ...in all the jokes and TV comedies that belittle Azeris

Shoghie: They don't let us teach our mother tongue in schools. They replace the Turkish name of our streets with Farsi names. And a lot of other prejudice too.

Mana: Mehrdad and I as journalists oppose this and are on your side... I don't know why we're the scapegoat here.

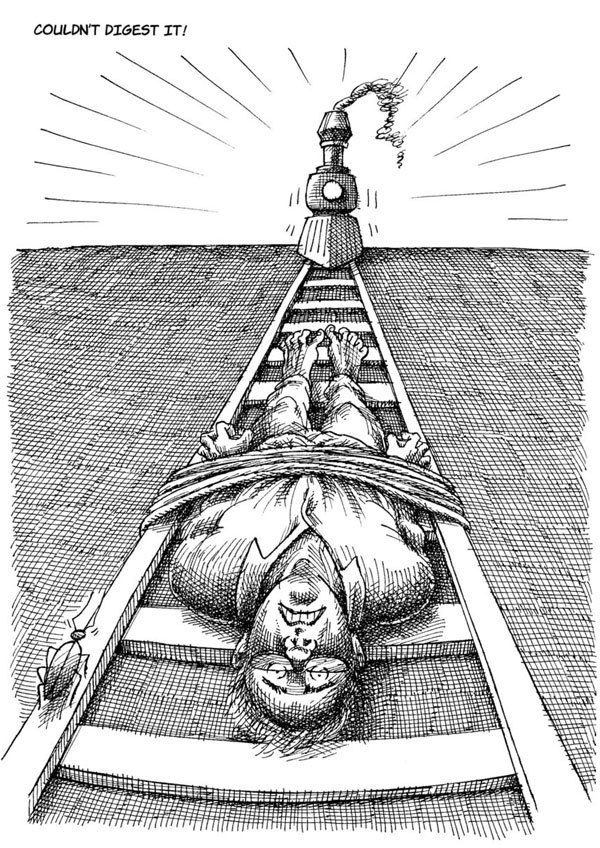

Shoghie: We have no personal problems with you or any other journalist but on the way toward the ideal there's a good possibility some people get crunched under the train of vicissitudes

[Couldn't digest it!]