From Drawn & Quarterly | Dog Days by Keum Suk Gendry-Kim, translated from the Korean by Janet Hong | Graphic Novel | 212 pages | ISBN 9781770467866 | US$24.95

What the publisher says: “Yuna never wanted to adopt a dog. But with her partner in mourning—and in desperate need of a boost in morale—she gives in to his humble request. And in the grand tradition of reluctant pet owners, she and their puppy soon become inseparable. The young couple even goes so far as to relocate from Seoul to soothe their new canine pal’s anxiety. After all, there’s nothing like a move to the country to set yourself right. Right?”

What Publishers Weekly says: “In Gendry-Kim’s windblown pen-and-ink illustrations, the dogs often loom over landscapes or dwarf the narrator, indicating the outsize place they occupy in their humans’ hearts. It’s a clear-eyed ode to the complications of living with both pets and people.”

What I say: Read enough comics and you’ll begin to notice the smaller things, including how some artists excel at depicting the subtle details of body language. What Keum Suk Gendry-Kim does here is especially impressive: the dogs that she’s illustrated move like, you know, actual dogs. Combine that with an affecting story of interpersonal drama and cultural conflict and you have a thoroughly absorbing graphic novel—and one that should resonate deeply with dog people everywhere.

From Riverhead Books | Clean by Alia Trabucco Zerán, translated from the Spanish by Sophie Hughes | Fiction | 272 pages | ISBN 9780593850510 | US$29.00

What the publisher says: “A young girl has died and the family’s maid is being interrogated. She must tell the whole story before arriving at the girl’s death. . . . Is this a story of revenge or a confession? Class warfare or a cautionary tale? Building tension with every page, Clean is a gripping, incisive exploration of power, domesticity, and betrayal from an international star at the height of her powers.”

What Maureen Corrigan at NPR says: “In its narrative structure Clean may sound like a suspense story, but it’s really a memoir-in-miniature narrated by Estela—a sharp woman who’s had to funnel her life into the rooms of her employers’ house. ‘Claustrophobia’ would have been a good alternative title for this novel, which is set almost exclusively in interior spaces.”

What I say: There’s a venerable tradition of the monologue as novel, and the way that Clean’s format shapes the reader’s perceptions of what they’re being told—and the looming sense of something terrible awaiting its characters—keeps the dramatic tension effective throughout. Alia Trabucco Zerán’s novel covers plenty of territory, from class struggle to fraught familial dynamics; in the end, it arrives at a place somewhere between tragedy and moral horror.

From 128 Lit | My Women by Yuliia Iliukha, translated from the Ukrainian by Hanna Leliv | Poetry/Fiction | 84 pages | ISBN 9798988447115 | US$20.00

What the publisher says: “Yuliia Iliukha’s My Women, translated from Ukrainian by Hanna Leliv, is an urgent and poignant story collection of women confronted by the countless brutalities of war. It locates the voices and devastating experiences of those who have been silenced, those who have lost loved ones, those who have fought and persevered, and those who have broken down.”

What I say: “I felt the inner need to talk about this war through the stories of women,” Yuliia Iliukha writes in the introduction to this slim but haunting volume. The stories told throughout are candid and sometimes visceral, as in the tale of a woman who “was eating herself for breakfast, lunch, and dinner.” In Hanna Leliv’s translation, the lives recounted here abound with a sense of loss, grief, and sometimes hope.

From World Poetry Books | The Light That Burns Us by Jazra Khaleed, edited by Karen Van Dyck, translated from the Greek by Peter Constantine, Viktoras Iliopoulos, Sarah McCann, Jason Rigas, Max Ritvo, Angelos Sakkis, Josephine Simple, Brian Sneeden, and Karen Van Dyck | Poetry | 192 pages | ISBN 9781954218246 | US$20.00

What the publisher says: “The English-language debut of Jazra Khaleed, one of Greece’s most radical poetic voices—now in an expanded edition—is an unapologetic indictment of the wrongs faced by immigrants, by a rudderless young European generation, by leftist activists in a Greece and a Europe blighted by neoliberal policies of deregulation and privatization.”

What I say: There’s a perceptible anger that runs through The Light That Burns Us when Jazra Khaleed describes the horrors of war. It’s present in these lines from “Requiem for Homs,” for example: “This war smells of soap and rope, / atropine and hydrocortisone, / this war sticks to hair, / bloats vertebrae, / burns the lips of elders.” Khaleed’s work manages to feel both idiosyncratic and widely applicable; that makes The Light That Burns Us a challenging and enduring read.

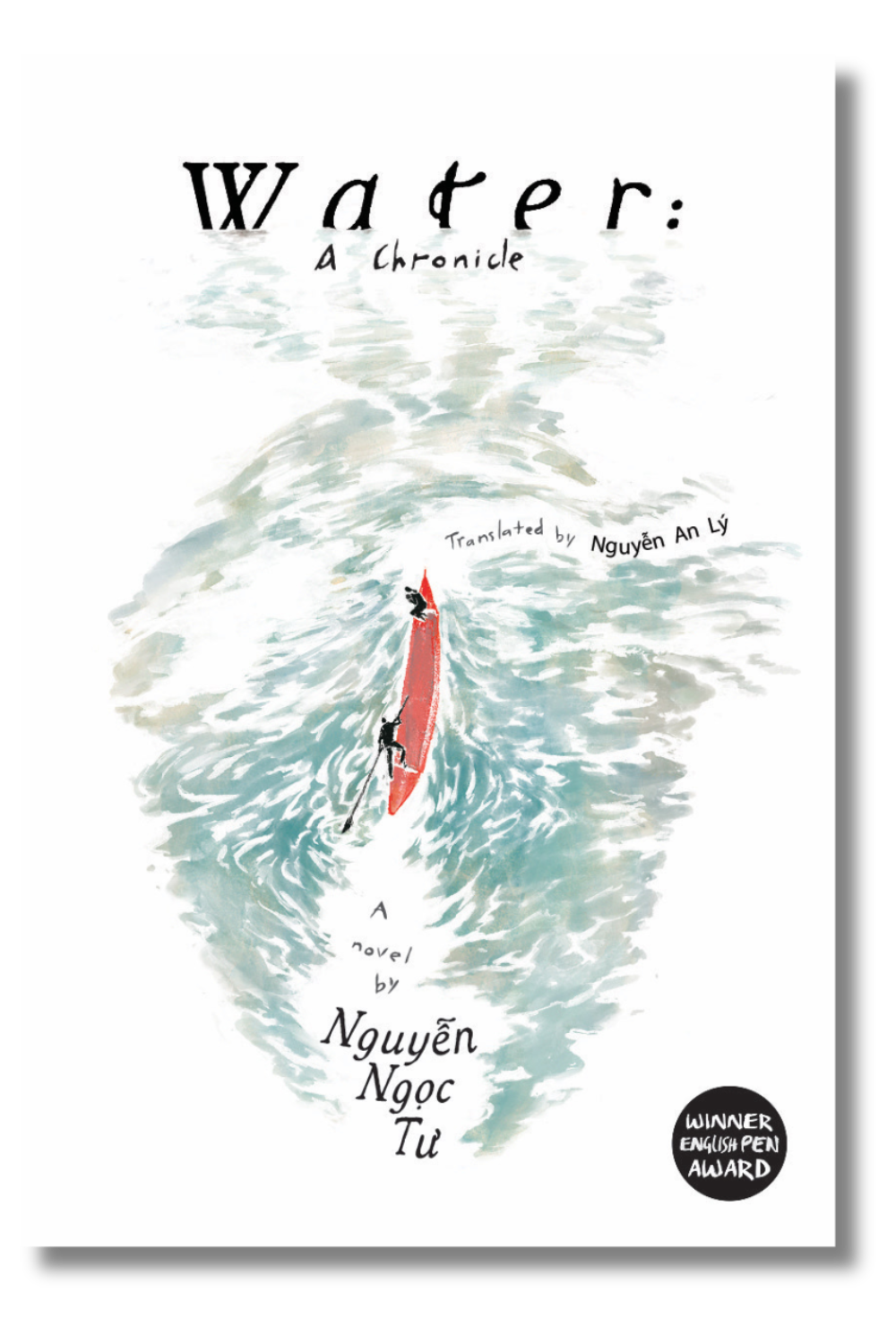

From Major Books | Water: A Chronicle by Nguyễn Ngọc Tư, translated from the Vietnamese by Nguyễn An Lý | Fiction | 122 pages | ISBN 9781917233002 | UK£11.99

What the publisher says: “At the heart of this watery ‘chronicle’ is a dual mystery: a holy man on an island empire, and a desperate mother seeking his heart to cure her child. The mosaic novel of nine stories circles this enigma like the river’s currents, carrying with it fragments of myth and life from the great river.”

What Thảo Tô at Asian Review of Books says: “Nguyễn Ngọc Tư plays with perceptions of reality, blending the supernatural with the real through her use of vernacular vocabulary—as opposed to extravagant literary language—building unique voices for her characters along the way. The laconic nature of her prose reflects her craft and confidence as an acclaimed short story writer who has won multiple awards in Vietnam.”

What I say: To immerse yourself in Water: A Chronicle to immerse yourself in Nguyễn Ngọc Tư’s tactile language, memorably rendered via Nguyễn An Lý’s translation: “They took the light away. They took the gold away. Darkness has inhaled the isle into its bottomless bowels.” In telling this kaleidoscopic tale of several interconnected lives, both writer and translator evoke a vivid sense of place. And the supplemental materials here, which explore the specific decisions that informed the translation, are especially informative for anyone curious about the process itself.

From Book*hug Press | Caesaria by Hanna Nordenhök, translated from the Swedish by Saskia Vogel | Fiction | 188 pages | ISBN 9781771669122 | US$24.95

What the publisher says: “On a remote country estate in nineteenth-century Sweden, a renowned obstetrician keeps a young girl named Caesaria as a trophy: she was the first baby he delivered by caesarean section. She lives a dollhouse existence, characterized by supervision and punishment, assault and incarceration. Told in lush, elegant, and dreamlike prose, Caesaria narrates her confinement in the doctor’s mansion and encounters with its mysterious inhabitants and visitors.”

What Daniel Pope at The Manchester Review says: “For much of the novel, the setting and farm animals dramatize the increasing violence that underpins the scientific appropriation of life and reproduction, but the true focusing agent of the novel’s themes is Master Valdemar, a young, wild-eyed man who may be a brilliant composer or may just be insane. Doctor Eldh, who meets Valdemar in his high-society circle, installs the man in the mansion so he can recover from an obscure psychic illness.”

What I say: There’s a moment a little less than halfway through Hanna Nordenhök’s Caesaria in which, in the span of a single paragraph, the narrator describes both cattle rutting and an accidental (human) disembowelment. It’s one of several points where this novel suggests a bleakness and a violence just below the surface of things; combine that with plenty of atmosphere and scientific mystery for a Gothic concoction that stays with you.

Looking for more reading suggestions? Check out Tobias Carroll’s recommendations from last month.

Disclosure: Words Without Borders is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and will earn a commission if you use the links above to make a purchase.