kafe bu naree neex su baxee xeeñ: the aroma of freshly brewed coffee never lies. Take it from a true connoisseur of tasty morning brews. As I always get up early, my first order of business is to head straight to the kitchen and put some water to boil on the gas stove. Then, setting it on low heat, I attend to other matters. When I return to the kitchen and set eyes on the splashing bubbles, it triggers in me such powerful emotions! I feel like a beachwalker immersed in the songs of toiling washerwomen as nearby birds twitter along, their calls echoing. Ci-ri-pi-ci-ri-pi-pi. Then I add ground coffee to the hot water and stir up the mix into a froth. The aroma of the steaming brew gradually fills every nook and cranny in the house. That’s when I’m gripped to the bone, all my body overcome with joy and happiness. I’m in such a rapture that I can’t help telling myself: “What a lovely day! Well, now I know what my last wish should be on the day Death comes for me!”

Everything is in the first sip: how the dark liquid courses through your throat, winds its way down to warm the bowels, untangling each in turn. I would give anything for this early morning kick, but only when the coffee is real. By real coffee I mean my beloved Lavazza, Segafredo, or Tirma. And, most treasured of all, my delightful Malongo. I never miss a chance to grab a box of Malongo, seeing that it’s so hard to find in Dakar, a fact that never ceases to amaze me. These fine coffee beans are the real thing, and so unlike the black powder in small plastic pouches they make you dilute in hot water, with one or two sugar cubes added to sweeten the flavor. Such a godawful mixture: at the first sip you can’t help wincing, your face twisted into a pained grimace, like a child forced to take nivaquine. Why would anybody want to go through such an unpleasant thing?

It was an ordinary Monday morning. Ever since I got up at the first crack of dawn, I had been working at my desk. As usual, I got out of bed before my husband, Bàrtélémi Gomis. I lay on the outer edge of the frame to avoid stepping over and inadvertently disturbing his sleep. Later on, Bàrt would swing by the little room I have turned into my personal study, to ask where things stood with my writing, cracking a couple of jokes, before going on about his own morning routine. Apart from his office work, there are only two things Bàrt cares to talk about: soccer and politics. So it was last night, when he pulled no punches in his bashing of Donald Trump: “What a fine president these foolish Americans elected last week! So now they have a dickhead who’s a verified idiot and, on top of it, flutters and twitches his eyelids like a you-know-what.”

The photos of Bàrtélémi and Xadi-Leena, our daughter who passed away in early childhood, look uncanny, as if they are scrutinizing me. Sometimes, when I turn my eyes on them, it brings back old memories.

Yelen—the name we used to call Xadi-Leena, while she was still alive.

There is a third photo, with a larger frame, of the late Kinne Gaajo.

Kinne Gaajo was everything to me.

“Who was this Kinne Gaajo?” you may ask, dear reader. Would you? Could you? I presume the name of our poetess laureate must ring a bell in everyone’s memory, here in Senegal. During literary discussions, Kinne’s name always comes up, almost like clockwork. You see, people firmly believe that God must have endowed Kinne Gaajo with the gift of poetry. In the notebooks I retrieved in Caaroy following her death in 2002, there is a moment where she fancies government officials desperately looking for ways to draw tourists and arouse interest in Senegal, telling potential visitors: “What are you all waiting for? Come, come to the land of teraanga, where peace rules supreme. Think this is another failed African state? Think again, ladies and gentlemen, because jungle politics is certainly not our thing. By the by, did you know that this country boasts several writers held in reverence all over the world?” Then they would drop a few names, and Kinne Gaajo’s always came first on their list of world-renowned Senegalese writers.

Every so often a name spreads so far out that an entire community comes to believe nobody else is entitled to bear it. When you say Maryaama Ba, Sémbéen Usmaan, or Baaba Maal, everybody thinks of the one and only Senegalese in the whole wide world who goes by such a name. To the three public figures I have just mentioned, I can add Kinne Gaajo. It’s been some time now since she passed away, but she still lives on in our collective memory. She makes us all very proud. Streets have been named after her in Ñetti-Guy, Caaroy, where she used to live, and in Tilaabéri, her birthplace. Children declaim her poems with the same fervor they put into reciting “Black Woman” by Lewopóol Sedaar Seŋoor and “Xarnu bi” by Sëriñ Musaa Ka.1 However, on second thought you realize that our Kinne Gaajo is better known abroad. Throughout all these years that I have been working on her biography, I have come across many translations of her works, endlessly commented upon in top draw universities. As everyone knows, her collection of poems Biddéewi diggu-bëccëg has sparked many controversies and quarrels; a couple of days ago I saw on television two academics debating it so ardently that they nearly came to blows. One of them had just published a voluminous monograph on Kinne Gaajo, claiming there was nothing arbitrary about the two words combined in the title. According to him, there is more to it than meets the eye: these are stars that ordinary people like you and me cannot set their eyes upon, unless we have what it takes: unusual acumen, focus, and gusto. Well, that’s how this scholar read the poem. Whether or not the poetess herself, if she were still alive, would agree with such an interpretation, I don’t know. Does it really matter? By design, books are supposed to be showcased, but their authors are far better off staying out of public scrutiny. This way, everyone is free to read into them whatever they please. Writers should always add this cautionary note to their readers: “A pen I can own, but a mind I can’t and won’t.”

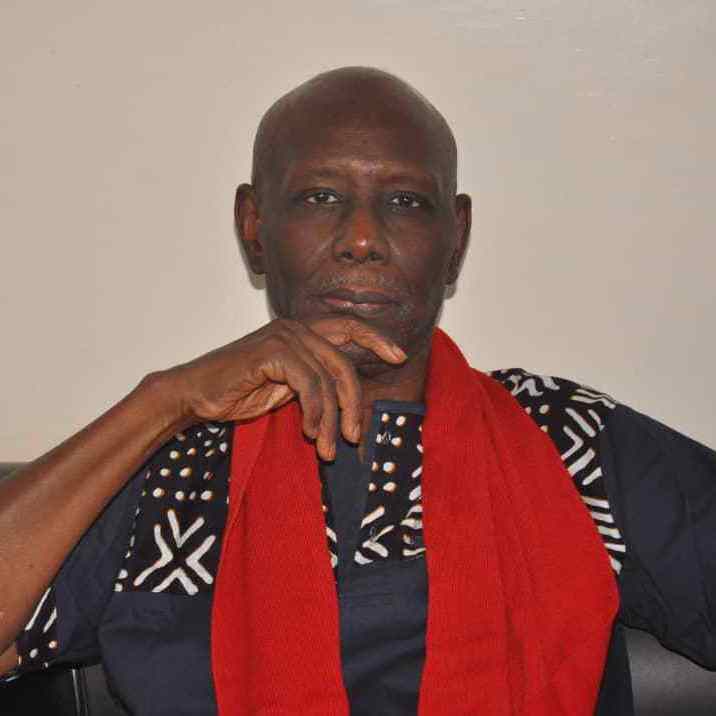

As I sip my now-cooled morning coffee, I stare intently at Kinne Gaajo’s oversized photo. Or I should say: the photo stares at me. I get the feeling it’s all up in my face, almost pressing down on my nose. When I close my eyes, I can sense her stern gaze boring into my forehead. Kinne is lying flat on the green grass. In the background, trees stretch their slender trunks high into the sky. To her right, three shining white pebbles are laid on the grass. One moment Kinne Gaajo is looking at me with a judgmental air, but the next moment, it is as if her eyes were merely looking over and above me, into distant horizons.

Nobody can look at this photo without a strange feeling of awe. You can’t help telling yourself that this woman is no ordinary human being.

Dear reader, please allow me to explain what I mean by that.

Writers have their peculiar ways, and far more than most ordinary people. Kinne Gaajo was no exception. In the picture, her face is painted white on the right side, red on the left, with a nguuka on her head, the lower ends twisted around the temples. A wood pipe is stuck in her mouth, and her eyes are bright like those of a savannah beast, say a lion or a cheetah. The inspiration behind this picture isn’t lost on me: Kinne Gaajo once offered me a Pongwa mask she bought in Libreville, Gabon. You see, she was redrawing the features of that mask on her own face. Some scholars may think this was the one and only time Kinne Gaajo, her face smeared with paint, summoned a photographer and bossily ordered: “Here, take my picture!” The job done, she paid the man, removed the paint from her face, and put her clothes back on. Well, it wasn’t. In fact, there are so many things about this enigmatic woman that are still shrouded in darkness. I remember that for months, every Friday she would paint her face white on one side, red on the other, wear her fancy headpiece and come pay us a visit, Bàrt and me, here in Sendikaa. The whole neighborhood would be watching, their eyes filled with compassion, feeling deeply sorry for her. “Poor girl, she’s completely lost it, hasn’t she? What a pity!”

Reader, as you hold this book in your hands, I can already see you struggling hard to puzzle the whole thing out, saying to yourself: “Goddammit! What’s all this got to do with you, lady? First of all, how come you are the one telling us about this Kinne Gaajo? What are your credentials? From what university did you graduate? What makes you think people will deem your words worth their time?” I smile wryly before countering: “You’re quite a wit, my friend. You see mischief everywhere, don’t you? Didn’t I just tell you Kinne Gaajo was a close friend of mine, that she was almost my soul-sister? Did I or didn’t I? Well, then let me make it my business to be a witness. That’s all there is to it. Look, my dear friend, I’m not prancing around like those academics deeply versed in literature, philosophy, or whatnot, and used to pontificating on Kinne Gaajo’s poems. Those heavies are too much for me to handle anyway. Every so often, I’m intrigued enough to read their writings on Kinne Gaajo, and you know what? It just makes my head spin, all I get out of it are bloody headaches, I don’t understand a word of what they’re saying. At some point I feel so dizzyingly confused I can’t help thinking that with all the stuff these smart people read into Kinne’s poems, whether it’s in Biir ak Biti, Abal ma sa Maam, or Guddiy Bomboloŋ, it’s quite likely a good deal of it is a figment of their own imagination.”

Kicking up a fuss isn’t my thing. There is only one goal I’m pursuing here: to get people to know a bit more about Kinne Gaajo. Be assured, reader, that if I knew someone out there more deserving of this lofty task than I, your humble servant, I would gladly defer to them. But you can look all around the world, and you won’t find anybody who can say they know Kinne Gaajo better than I do.

So reader, the fact that today you are holding Bàmmeelu Kocc Barma in your hands is not mere coincidence. A book can’t just write itself; somebody has to do it. That’s the first step. Once that task is complete, you, my dear friend, can then take the next one: go grab a copy and start reading. No sooner are you done with a chapter than you are on to the next, feverishly turning the pages. It’s like taking a pleasant stroll with the author, exchanging views on all kinds of topics. Now and then, feeling in a light mood, you are like two kids playing and toying around so much that the grown-ups must chidingly intervene: “Hey, you two little devils, what are you up to? Stop fooling around before you get hurt.” For weeks, maybe even for months, that’s how you and the writer will have it going. But in the end, this doesn’t get you any closer to each other. Here is a thing you need to know then, dear reader: once you’ve started delving into this book, and its characters are tickling you on the sides and pulling at your heartstrings, I’m sure the voice whispering into your ears will come to sound a bit familiar, but other than that whiff of familiarity, you will know next to nothing about your mysterious confidant.

It doesn’t always have to be like this.

The way I see it, a writer must tell her readers who she is before going any further. Imagine you are a long way from home, and you arrive at someone’s compound. You knock on the door, the gates are pried wide open, and now you stand in the courtyard. The first thing to do is greet your hosts politely, all the more so since you claim to have a story to tell and everybody in the compound must stop whatever they are doing and pay attention.

So, dear reader, allow me to first introduce myself: I’m Njéeme Pay.

In all likelihood you have never seen me, although you must have heard my name here and there, given that as a journalist I enjoy some sort of popularity in Senegal. I’m part of the pioneering generation that, back in the day, set up radios all over the country. As when a wrestler in his prime stakes his claim by planting a drum deep in the middle of the arena, what we did was meant as a gesture of defiance. Of course, when we decided on the name Péncoo FM, we knew we were asking for trouble, we knew the powerful would never let us do our job properly. But we did what we had to because our only drive, back then and right now, is to amplify the voice of the people, while making sure that anything said on air is true and accurate.

For us it was a simple equation: as long as they kept on with their wrongdoing, we, radio journalists, had to keep on airing the truth, nothing but the truth; as long as elected officials kept on misappropriating our taxpayers’ money, we, radio journalists, had to keep on screaming, “Thief! Stop the thief!” Anyone peddling bald-faced lies in public should be exposed, so we wasted no time in calling the bastards out: “You filthy liar! You’re such a disgrace! Shame on you!” All that, and more, we did out of a genuine desire to chase deceit and dishonesty out of the land, so that our dear Senegal could finally take off.

Doubtless, it was in my work as a radio journalist, when you and I were socializing every so often, that you got used to hearing my voice on the airwaves. For all that, you can’t claim to have ever set eyes on words written with my own hand. This is a first, and so in the coming days I’ll keep you company with this book I have decided to call Bàmmeelu Kocc Barma—Kocc Barma’s Gravesite. Once you have plunged into it, you’ll come to understand what this title means. Indeed, you’ll come to realize it couldn’t have been called otherwise.

Let me repeat: this is the story of the late Kinne Gaajo.

You and I are getting to know each other little by little, aren’t we? Good. Suppose you even forget about the book, just for a moment, and go on YouTube? There you’ll find short clips of Jaar ci digg bi. This radio show of mine consists of sit-down interviews with high-profile politicians. Believe me, the latter keep lying through their teeth, on and on. Yet I make sure the bastards don’t get away with it, I grill them so hard that, right then and there, they get tangled up in a web of inconsistencies and inaccuracies of their own making. Simply put, I never let them off the hook.

Now would be a good time for you to ask: “And what got you into this line of work, radio journalism?”

By way of an answer, let me tell you a little story.

Among God’s bits of wood, there are some who know what they want to be at a very early stage in life, long before they reach old age. God has endowed them with power and intelligence, so that they can muster enough courage to choose for themselves. One will say, “When I grow up, I want to be a doctor!” Another will say, “As for me, I won’t be happy until the day I’m dressed like a lawyer, in a black robe with white collars and cuffs. I’ll right wrongs, I’ll stand up and plead noble cases in court. I’ll speak up, I’ll be fearless, and I swear to never back down until I have prevailed against the powerful trying to lock up the weak in a dark hole.”

Today there stands in front of you someone who always wanted to be a journalist: me. The same year I was handed that little scrap of paper they pompously call “baccalaureate,” I enrolled in CESTI, the local school of journalism. I put all my pride and self-esteem into it, paving my road to success with steely determination and a driving sense of purpose. Nothing in that plan of mine could go wrong. So I thought, anyway.

As a journalist, all you have to do is collect and spread information. You create or add nothing to it, even though once in a while you may insert a little allusion here, make some word changes there, tweak it enough to sustain people’s interest. Take it from me: when it comes to spicing things up, I have no match. However, as far back as I can remember, there was never a time when, sitting at my desk, I was tempted to say, “Now, Njéeme, how about you spin a nice little yarn and cast it as news? Given that listeners tuning into Walf FM, Zik FM, or Péncoo FM are such gullible dimwits, you might as well take them for a nice little ride, eh?”

A story that could go like this: Once upon a time, there was a beautiful woman by the name of Sira Jànke. Her master, Simbi Nungaa, was a tyrannical husband with a scar-studded body that inspired nothing but dread. One day, Simbi Nungaa set out on a trip to Heaven, where he had an appointment with an angel whom he had asked to craft a bracelet out of a piece of the sun—you heard me right, the man didn’t want a bracelet made from mere gold or copper, but from the big yellow sun itself. So up went Simbi Nungaa toward the skies, up and up, cutting through clouds. Once he cut through the last cloud formation, he shot a glance back down at his house on Earth, deep in the Saxañoor forest. He couldn’t believe what he saw with his own eyes: his wife was gathering her belongings and running away from the household to seek refuge in her father’s compound! The truth is, until that moment, little did Sira Jànke suspect that when she entered into this marriage she had taken as husband an evil jinn who would regularly suck the blood out of people and eat human flesh. As Sira Jànke shut the door behind her, Simbi Nungaa thundered from Heaven, asking why she was taking their child with her. He worked himself into such a frenzy that he started kicking the clouds around him and, in an angry refrain, urged the angel-jeweler to make it fast:

Tëgg bi tëggal ma gaaw sama jabar a ngay dem!

Tëgg bi tëggal ma gaaw sama jabar a ngay dem!

Tëgg bi tëggal ma gaaw sama jabar a ngay dem!2

Simbi Nungaa kept at it, on and on, the thunder making his baritone voice reverberate, the whole celestial dome shaking. As he flew back to Saxañoor, kicking and trampling the clouds underfoot and the solar bracelet shining bright in his hand, concrete buildings collapsed, trees fell down, their roots yanked off the earth, and wild animals scattered all over the forest in a mad rush for shelter. What about our little Sira Jànke? Well, the poor girl knew she was done for. She was so frightened she could hear the heavy pounding in her chest. Ba-boom, ba-boom, ba-boom.

Now, dear reader, if you want to know what Simbi Nungaa, that mean-spirited demon, did to Sira Jànke when he found her by the curbstone of a well, ask a wandering storyteller the next time you come across one. The last time I, Njéeme Pay, was anywhere near the curbstone of a well, I was just a little girl running around Tilaabéri, my native village, with Kinne Gaajo, our bare feet covered in dust. It’s a golden rule with me: if I wasn’t there when it all happened, it’s none of my business.

I’m not what you would call “highly educated,” but here is what I can tell you with some assurance: there is nothing sillier than to stand in front of dignified heads of household and tell them a cock- and-bull story not even a toddler would believe. So put this in your head, dear reader: this book, Bàmmeelu Kocc Barma, is no work of fiction. And if you pester me with all kinds of questions, I’ll say this is not even about Kinne Gaajo’s life story, this is about her as living history. Why do this only now? To pay my debt, make our bond stronger, and deliver on a pledge I once made to Kinne Gaajo. Nothing else is driving me. Hopefully, soon enough you’ll get the point.

At this stage, you may feel like pulling out of this merry-go-round by asking me: “Do you really have a story to tell, lady? What’s this life story and living history nonsense? What’s all this beating around the bush? For God’s sake, can’t you cut straight to the chase, say your piece, and leave?”

Again, I smile wryly. My dear friend, you see, these embellishments can’t be helped. You know how it is with us women: we like to spice things up . . .

However, if you are in too much of a hurry and your patience is already wearing thin, we can bid each other farewell. Right here, no hard feelings. Sweet and pleasant is the company of our fellow humans, but when they’re gone, they’re gone. If you do leave, just don’t expect me to lean on your shadow to laugh or cry.

Are we on the same page, dear reader?

From Bàmmeelu Kocc Barma. © Boubacar Boris Diop. By arrangement with the author. Translation © 2022 by El Hadji Moustapha Diop and Bojana Coulibaly. All rights reserved.

1. “Xarnu bi” (“The Century”) is one of the earliest known poems written in Wolofal, the ajami script used by Sëriñ Musaa Ka (circa 1890–1966), a pioneer of Wolof literature. The poem deals with the 1929 global economic crisis.

2. The refrain roughly translates to “Jeweler, make it quick, my wife is leaving me!”