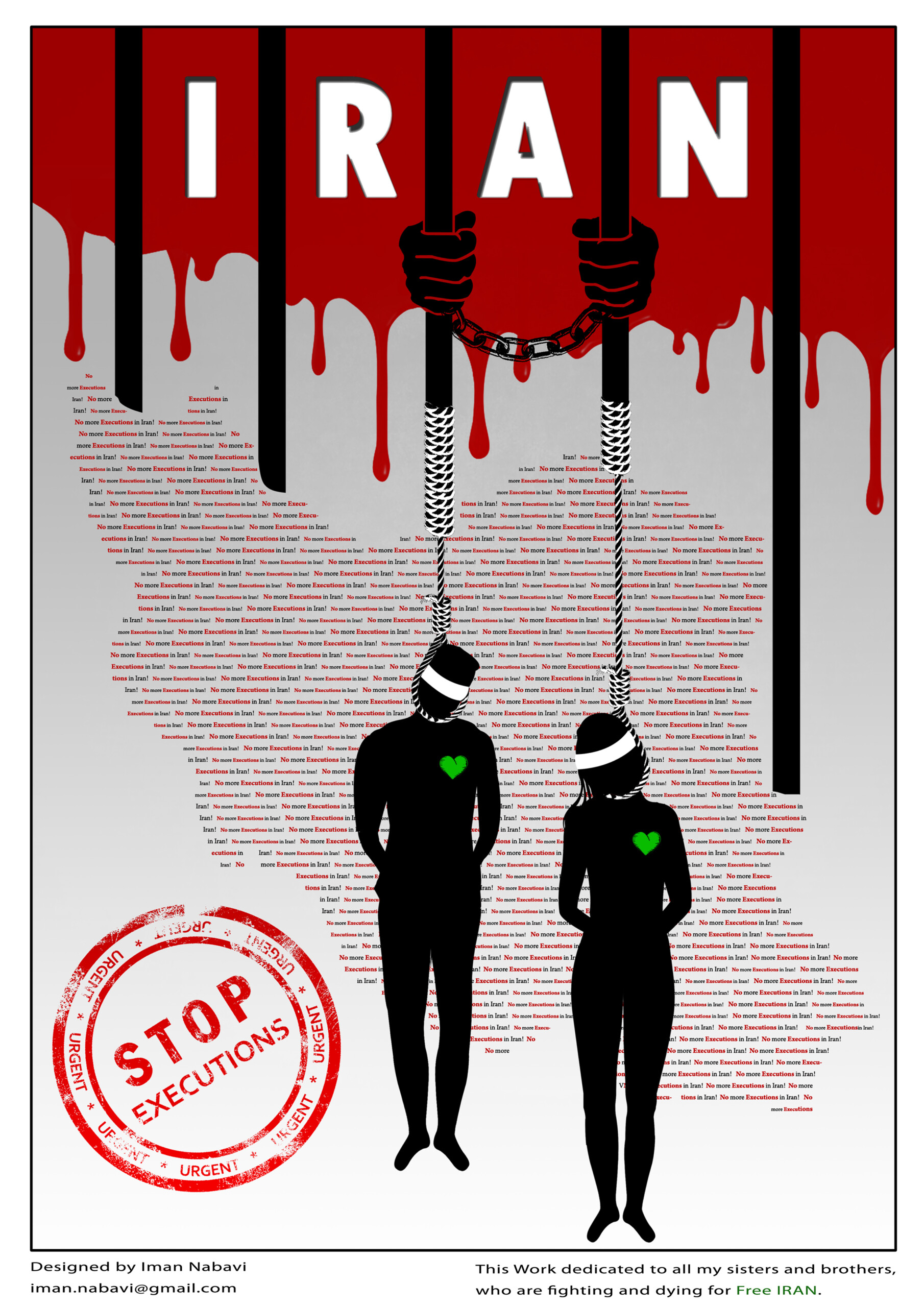

Poster designed by Iman Nabavi

Every night I wake up several times. I have nightmares of executions. Images from the ten public executions I witnessed as a reporter in order to write about them over the past several years keep moving in front of my eyes as if they are frames of a movie being rewound and fast forwarded. The most persistent image is that of the two men in their twenties who were hanged on the north side of Artists House Park. It was dawn, after the morning call to prayer. Their necks were broken by the rope, and, suspended in the air, their bodies kept swinging like two dolls. The screaming and howling of women, said to be their mothers and sisters, came from the police kiosk nearby, filling the air and swirling through the trees in the park.

Two nights ago, I woke up with the memory of these women’s shrieks. Another night, with the image of one of the young men, his hands tied and his eyes covered, asking for water before he was hanged. The guard who stood next to him brought the water container to his lips, and the young man gulped it down in absolute silence. Really, how have I been able to peacefully drink water in all the years since I saw that scene? This time, I wake up and remember that the two men were hanged for stealing, by use of force, a bag that contained 70,000 Tomans (the price of seven baguettes). I take some pills and struggle to fall back asleep.

It’s seven in the morning when I wake up. These days, not only I but millions of Iranians start their mornings by checking social media for the latest news from the uprising. “Majidreza Rahnavard, one of the arrested protestors, was hanged this morning in Mashhad in the presence of an audience,” I read. I burst out crying out loud.

A long list of the names of the youth who have been sentenced to execution for the so-called crime of “enmity with God” was published a few days ago. I had seen Majidreza Rahnavard’s name on the list, but I never imagined that he would really be hanged. We all had thought the imminent threat was to Mahan Sedarat and Hossein Mohammadi and had been hashtagging their names on social media. But now Majidreza Rahnavard . . . He was sentenced and executed just twenty-three days after his arrest, without access to an independent lawyer, for the alleged crime of killing two guards.

There is word that regime officers called his family around seven in the morning (one hour after the execution), and informed them that their son had been hanged during the night, while they were asleep, in one of Mashhad’s streets in the presence of a crowd, and that he was buried in lot sixty-six of Behesht-e Reza. Behesht-e Reza is the main cemetery in Mashhad, one of Iran’s most sacred cities in the eyes of the religious—the site of the Holy Shrine of Imam Reza, the eighth imam of the Shiite Muslims, the city that has been in the spotlight in the past few months because of the movie Holy Spider.

I keep wondering who answered that phone call from hell, and what their reaction was. Did Majidreza’s mother let out a howl? Did his father faint? How did his family get themselves to Behesht-e Reza and the freshly dug grave of their son? Sometimes the paradoxes here become too much to bear; the cemetery Behesht [heaven] turns into hell for Majidreza Rahnavard’s family and millions of other Iranians. My tears start to fall. I imagine the moment Majidreza’s mother threw herself over the pile of soil on her son’s grave and screamed his name. My own mother’s words keep hammering over my head. She called me a few days ago to beg me not to take part in the “No More Executions” protests that were to be held after Mohsen Shekari’s execution, the first to be carried out of the young protestors arrested. When I told my mother that Mohsen Shekari too was another mother’s child, she cried on the phone and said, “You haven’t been a mother to understand what I’m saying. For my sake, don’t go, son.”

I click on the list of the arrested protestors who have been sentenced to death and anxiously read the names, one after the other, terrified of who might be next: “Saeed Shirazi, Mohsen Rezazadeh Gharegholou, Mahan Sedarat Madani, Sahand Nourmohammad-Zadeh, Mohammad Ghobadlou, Mohammad Boroughani, Saman Seydi, Mohsen Shekari, Toomaj Salehi, Majidreza Rahnavard, Mohammad Mehdi Karami, Seyd Mohammad Hosseini, Arian Farzamnia, Amin Mehdi Shokrollahi, Reza Aria, Mehdi Mohammadi, Mohammad Amin Akhlaghi, Behzad Ali Kenari, Javad Zargaran, Shayan Charani, Hamid Ghare Hasanlou, Farzaneh Ghare Hasanlou, Amir Mohammad Jafari, Reza Shaker, and Ali Moazzami Goudarzi[1].”

I can’t stop my tears when I get to Mohsen Shekari’s and Majidreza Rahnavard’s names.

Will another young person be hanged tomorrow, their name to be cut from this list?

[1] For the latest updates to the list, please check the Amnesty International and HRANA (Human Rights Activists News Agency) websites.

© by Anonymous. Translation © January 2023 by Poupeh Missaghi. All rights reserved.