We bumped into each other on the train.

Antonio, returning from A Coruña:

me, heading to Vigo.

We greet with air kisses —smooch, smooch—

and he soon asks after Oscar.

I lie to him,

“haven’t seen him in a year”

and he wrings his hands.

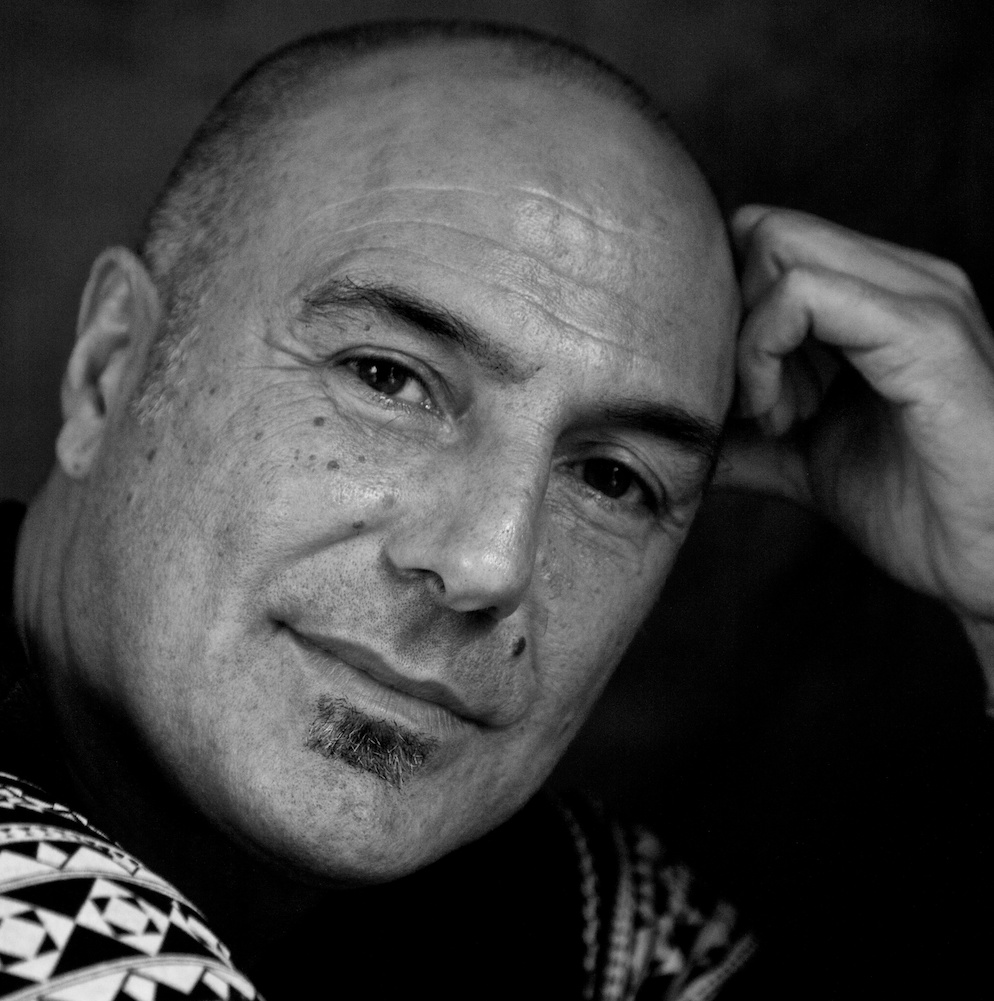

He’s put on weight.

“It’s the anti-depressants,”

he says indifferently

and flips his hair back.

It’s dirty. He laughs,

“didn’t find anyone with a shower

this weekend”

and his sweater smells strongly of tobacco and there’s a staleness

to his skin, a mustardy color,

but he’s still an incredibly good-looking man,

with that gaze you can dive into and lose yourself,

and half-open lips,

thirsting.

An inexplicable beauty,

as beauty always is.

He’s uncomfortable because I’m observing him

and from his knapsack he pulls out a book with a rumpled cover

and pages yellowed by sun and damp.

He waves it at me to

distract me:

it’s Mishima’s The Decay of the Angel.

He found it in a used bookstore and

admits he’s already read it a few times.

He’s obsessed by the character of Kinue

and from how he says it,

I suspect something in Kinue

reminds him of his own life.

“I dunno,”

I say to him,

“I read a Mishima novel a long time ago

and it didn’t really grab me.”

He’s taken aback:

“How could anyone not love

Mishima?”

“You really want to know?”

“Here goes! Kinue’s horrid, the quintessence of ugliness but she’s sure she’s the most beautiful

woman in the world and that she suffers as only beautiful women do when they walk down

the street and all eyes are on them, when she takes a bus and men rudely try to sit down

beside her, when she constantly feels men at dances drooling over her, men who would, if

they could, engage her in the most indecent acts.”

I ask if that’s how he feels

and he pulls out a wrinkled cigarette from the pocket

of his shirt.

“I can’t offer you one,”

he says,

“it’s my last.”

“No problem: I don’t smoke anymore.”

“To your health, then,”

and he lights the cigarette.

He exhales smoke the way a flautist, in fine-tuning the air,

extracts from it a strange music.

The smoke slips away,

“to be honest, I admit that I’m

bored,”

and he looks out the window.

“Bored by what?”

“By all this: by the city, by Monday morning trains, by hookups, by all those who fall for me, those

who go wild for me, those who are starstruck, entranced when they see me, and who shower

me with promises,

marvelous promises: a beach getaway, a trip to Barcelona to get wasted, brand-name clothes, a

nice cologne, dinner in an expensive restaurant.

Some swear they’re serious, and at times

I’d say they’re serious, but in the end,

they are all scared to death.”

“Scared?”

“Terrorized.”

“I don’t get your drift.”

“Having something like me at your side means responsibilities and obligations. It seems

everyone’s

waiting for something and, in reality, they’re

too self-satisfied to wait for anything

that’s not a paperweight

sitting

right on top of the table.

A stunning companion who provokes

admiration from friends

and envy from enemies

exclamation from passersby

and joy at a fulfilling reflection in the mirror.”

I interrupt his soliloquy:

“It seems like you’ve been thinking about this for awhile.”

He taps a finger to his head:

“I’m on my own, by myself and with lots of time to think.

I’ve been learning this for 25 years.

Do you know

how it feels to know exactly how everything will play out?”

He finishes the cigarette and stubs it out in the armrest ashtray.

“They approach me and get an idea of me and expect me to surprise them without budging an

inch from their idea of me, and I’m not playing that game.

They love me not for myself but for what I represent, and when I give them proof, when I extract

from beauty what I actually am, it paralyzes them.”

“You mean you play them?”

“In a way, yes:

Some I just piss on in the library storeroom,

to others I just say no, that I don’t care to be with them,

that I’d rather smoke and watch them, that I’d rather drink coffee then spill it down my shirt, that I have no cash, that I need cash,

that I’ve a fine to pay, that I have insomnia, that my Dad’s a Fed, that I still haven’t finished

high school, that I’ve been arrested three times, that I’m a sleaze, I have panic attacks, I’m

impatient, that some nights my wrists tremble and glasses fall out of my hands and I don’t

know what to do with my hands and I wring my fingers.”

“Sounds hard to take.”

“And what about them? Don’t they have it worse? It’s not me who tragically realizes that love is

rotten to the core.

My tragedy is

confronting the truth that no one can love me: they don’t love me, or even need me:

they just possess me.”

He tenses and twists

his lip in a histrionic

wince

at the corner of his mouth.

It’s clear he’s ready for another cigarette.

He stands and bums one from a girl at the far end of the car.

Her face goes suddenly bright and a shudder of nervous laughter rises from the girls with her.

They poke each other. A gum-bubble bursts on one’s face and makes her blush.

He returns sucking anxiously on the cigarette.

“You see? Everything seems easy at first . . . but that initial reaction is not to me but to the beauty

that imbues me.”

“You’re just obsessed. You’re handsome

but it’s no big deal.”

“Don’t be so superficial!”

“I’m not being superficial:

I can see you’re not a happy guy.”

“How can I be happy if I can’t find anyone who loves me?”

“And you? Do you love anyone?”

“No one gives me time to!”

“Maybe you don’t give them the chance?”

“I give them plenty of chances, but they always end up turning back to their money, their

bookshelves, their shirts . . . even you,

do you think I don’t see how you’ve looked at me

all these years? It’s an opaque, cowardly desire, the most cowardly of all because you fear I’ll notice. Or worse: not that I’ll notice but that other people will.”

“I think you’ve got me wrong, you’re mistaken.”

“Do you think I don’t see the pack of tobacco tucked in your jacket,

though you say you’ve stopped smoking?”

“I think that beauty is too narrow a path for those whom it keeps from sleeping.”

He bursts into a splendid peal of laughter, all teeth

and I pull a Walkman out of my jacket—

“It’s not tobacco, it’s music”—

and set it down on the seat beside me.

He picks it up and leans back,

“I knew it was music: I was only trying to bug you”

and unbends his legs. They’re long.

He slides one forward aside my seat

to give it a stretch.

He sighs,

“we still have half an hour before Vigo,

want to head to the toilets?”

Fálame © Esquío 2003 Antón Lopo. English Translation © 2021 Erín Moure. All rights reserved