In the National Museum of Beirut, an exquisite Byzantine mosaic with animal motifs bears a gaping hole in one corner. The wall-mounted mosaic, The Good Shepherd, was damaged by a sniper during the Lebanese civil war of 1975–91, as militias overran this Egyptian-revival landmark on Damascus Road. Many Phoenician, Greco-Roman, and Byzantine treasures from the country’s multilayered past were safely bricked up in the basement or encased in concrete by the museum’s resourceful director, Maurice Chehab. But after the museum reopened in 1999, the battle-scarred mosaic was left unrestored as a fragile totem of the madness of war and the dedication of those who resisted it.

‘The Good Shepherd’ mosaic in the National Museum of Beirut (detail), its left corner damaged by a sniper. Originally from a church in Jnah, Lebanon, 5th–6th century CE. Copyright © Maya Jaggi.

Known simply by the Arabic for museum, “Mathaf” sits on the wartime Green Line that divided Christian East Beirut from the capital’s mainly Muslim West—a lethal strip of no-man’s-land where rival militias faced off. Farther north, toward the Mediterranean port, the yellow sandstone Beit Beirut (Beirut House) reopened in 2017 as the Museum of Memory. Built in the 1920s, this elegant neo-Ottoman apartment building became notorious as a snipers’ den. Saved from postwar demolition by a dogged campaign, its bullet-ridden structure has been scrupulously frozen in time. Upstairs, the gunmen’s sandbagged nests give a chilling insight into how militiamen, immune to incoming fire, would shoot clean across the building’s interior and out the other side, omnipotent lords of the streets they terrorized.

Yet such salutary reminders of the civil war are rare in a city seemingly intent on forgetting. Beirut’s ruined Ottoman heart was razed, not renovated, to be replaced by concrete souks and Dubai-style high-rises. This sanitized, soulless downtown is known to many Beirutis as “Solidere,” after the controversial company that transfigured it. The blackened ruin of the Holiday Inn still towers over the Bay of Beirut with its palm-lined Corniche. But it is officially forbidden to photograph the charred remains—a fiat defied by artists.

In Lebanon, “we’ve been champions of forgetting in a most negative way,” the novelist and essayist Dominique Eddé told me at a cafe in Clemenceau, western Beirut, this past fall. “The country has no inhibition toward destroying its past like a bulldozer. It’s merciless and fascinating—it speaks of a huge vitality. But how do people’s minds and memories adjust?”

The civil war was suspended some thirty years ago without a formal peace or reckoning. School textbooks leave off in 1943, with Lebanon’s independence from the French mandate. Even “civil war” is a moot term to describe a succession of wars and massacres among proliferating militias in shifting alliances, sponsored by foreign powers including Syria, Iran, Israel, and Saudi Arabia. Yet, with no consensus on history, and an official amnesia imposed from above, Lebanese literature—in Arabic, French, and English—has been a stubborn repository of personal memory; a space to question the formation of history, as well as sectarian identities made more rigid by war.

That the remembered past weighs heavily on the present was clear from the protests that began, in fall 2019, in Beirut’s Martyrs’ Square on the former Green Line. Spreading throughout Lebanon, they mobilized people across sectarian lines in an unprecedented rejection of the postwar status quo. The so-called October 17 Revolution—the country’s biggest demonstrations since the Cedar Revolution of 2005 ousted the occupying Syrian army—prompted the resignation of the prime minister, Saad Hariri, on October 29. Ostensibly sparked by a youthful rebellion against a tax on WhatsApp calls, it was stoked by widespread anger against corruption and economic mismanagement, amid the daily attrition of power cuts, lack of clean water, and festering trash heaps. But the mood was caught by men and women of all ages, Sunni and Shia, Maronite and Druze, joining hands in a 170-kilometer human chain that ran through Beirut, from Tripoli in northern Lebanon to Tyre in the south. Targeting an entire ruling class—some of whose sect-based parties are still headed by wartime militia leaders—these demonstrations have been hailed in some quarters as the definitive end of the war, and the beginning, at last, of a healing process of memory and reconciliation. As one slogan against those in power ran: “We are the popular revolution. You are the civil war.”

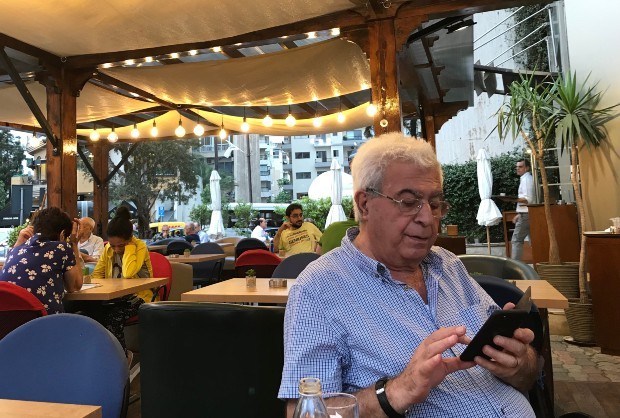

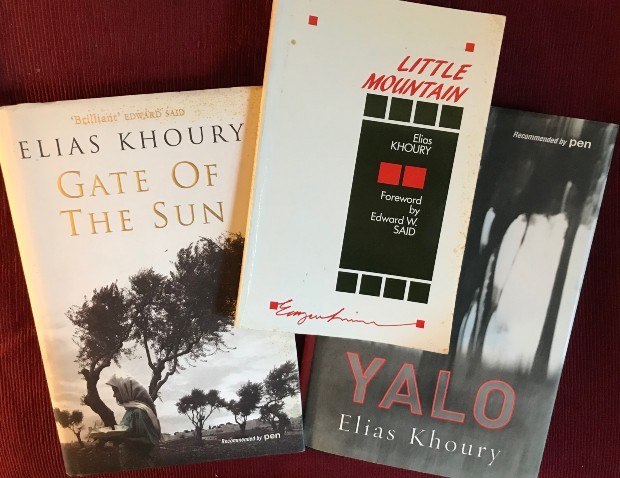

On the eve of the protests, I spoke with Elias Khoury, one of Lebanon’s leading novelists and formerly global distinguished professor at New York University, who has described Beirut as the “capital of amnesia.” We met near his home in eastern Beirut after tire-burning protests—a harbinger of the October 17 demonstrations—had erupted in the Palestinian refugee camps of Sabra and Chatila in south Beirut. The 1982 massacres in these camps—among the worst atrocities of the civil war—are at the heart of Khoury’s 1998 masterpiece Gate of the Sun (whose English version by Humphrey Davies won the inaugural Banipal Prize for Arabic Literary Translation in 2006, when I was a judge). The novel—which now has a sequel, Children of the Ghetto: My Name is Adam (2016; translated by Davies in 2018)—wove a tentative oral history of the Palestinian Nakba (catastrophe) of 1948 from the persistent memories of love, flight, and dispossession that Khoury heard in Beirut’s camps.

Writer Elias Khoury at a café in Achrafieh, Beirut, fall 2019: “The civil-war collapse of the nation-state exploded the Lebanese novel.” Copyright © Maya Jaggi.

“The dominant amnesia is not really about forgetting,” Khoury cautioned. “The militia leaders now in government imposed a collective amnesia, but that doesn’t prevent each community from having its own memory. It creates separate memories that can emerge at any time and cause another war.” In Gate of the Sun, he wrote that “memory is the process of organizing what to forget.” Yet, “especially after terrible wars like ours, that work wasn’t done,” he told me. “You have to forget in a decent way; to mourn so you can live. But you need to feel the victims are respected.” Instead, “when the Syrians imposed peace, there was a general amnesty [in 1991] so none of the war criminals governing us could be questioned. At least 17,000 people disappeared during the war. Till now, we don’t have a hint of where they’re buried.”

We were sitting on a café terrace in traffic-filled Sassine Square, in Achrafieh, the hilly district known as Little Mountain where Khoury was born in 1948 into a Lebanese Christian family. A leading journalist and critic who worked with the poets Mahmoud Darwish and Adonis when prewar Beirut was a dynamic hub of Arabic publishing, he said the war reinvented Lebanese fiction: “The novel is the outcome of the bourgeois nation-state. But here, the collapse of the nation-state exploded the novel. Civil war opened the windows of reality, bringing in colloquial Arabic and an avant-garde stylistic approach to the details of daily life.”

Khoury’s wartime involvement with left-wing and Palestinian forces (Christian and Muslim) had exiled him to West Beirut. Little Mountain, written in Arabic in 1977 in the midst of the fighting (and published in Maia Tabet’s English translation in 1989), was one of the war’s first novels—along with Etel Adnan’s Sitt Marie Rose (1977) in French. A picaresque narrative of a youthful urban guerrilla, his family home raided by militiamen wearing crosses who target him as a traitor, it expressed the author’s disillusionment as all sides became implicated in atrocities, and melded memoir, pastiche, and fable into a restless, fragmented, postmodern form.

First edition of Elias Khoury’s novel Little Mountain in English translation (Maia Tabet; University of Minnesota Press, 1989) with later novels. Copyright © Maya Jaggi.

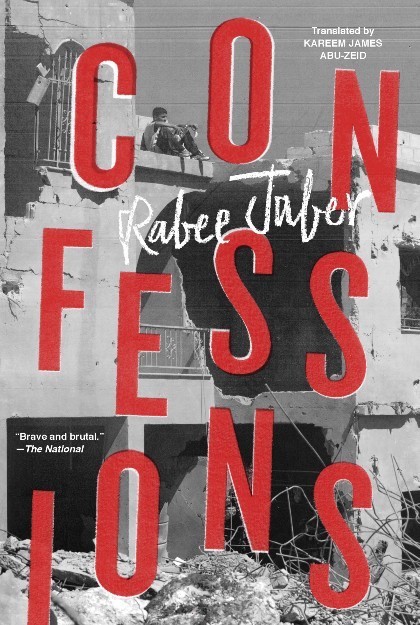

Khoury is among Lebanese novelists whose fiction unsettles sectarian identities. His novel Yalo (2002; translated by Peter Theroux in 2008), exploring memory and truth through a man’s unreliable confessions under torture, has an antihero who is Syriac and Kurd, Muslim and Christian. In Jabbour Douaihy’s Chased Away, Nizam is born a Muslim and raised a Christian. In Rabee Jaber’s punningly titled Confessions (2008; translated by Kareem James Abu-Zeid in 2016), the narrator, Maroun, is the adopted son of a man from Achrafieh who orphaned him, killing his parents at a roadblock before kidnapping the boy and naming him after his own dead son. Maroun pieces together an unspoken history of his adoptive father’s atrocities—including the Karantina massacre of 1976 near Beirut port—from fragments of hearsay. Blanketed in silence, and without a solid framework of historical facts, such characters struggle to make sense of their own memories.

Khoury is among Lebanese novelists whose fiction unsettles sectarian identities. His novel Yalo (2002; translated by Peter Theroux in 2008), exploring memory and truth through a man’s unreliable confessions under torture, has an antihero who is Syriac and Kurd, Muslim and Christian. In Jabbour Douaihy’s Chased Away, Nizam is born a Muslim and raised a Christian. In Rabee Jaber’s punningly titled Confessions (2008; translated by Kareem James Abu-Zeid in 2016), the narrator, Maroun, is the adopted son of a man from Achrafieh who orphaned him, killing his parents at a roadblock before kidnapping the boy and naming him after his own dead son. Maroun pieces together an unspoken history of his adoptive father’s atrocities—including the Karantina massacre of 1976 near Beirut port—from fragments of hearsay. Blanketed in silence, and without a solid framework of historical facts, such characters struggle to make sense of their own memories.

The Paris-based novelist Amin Maalouf traces fluid identities back to the region’s pluralistic past in novels such as the Prix Goncourt–winning The Rock of Tanios (1992; translated by Dorothy S. Blair in 1995), set in early nineteenth-century Lebanon as the seeds of sectarian bloodshed were sown. Jaber, too, looks beyond living memory for clues to the present. His novel The Druze of Belgrade, which won the International Prize for Arabic Fiction (the “Arabic Booker”) in 2012, is set in the aftermath of the 1860s civil war, as 500 Druze rebels found guilty of massacring Christians are ordered to a Balkan jail by the Ottoman pasha. When one bribes his way out, a hapless hawker in Beirut port—ironically, a Christian—is incarcerated in his stead. An unlucky innocent, he could just as easily be of the wrong faith or sect at a checkpoint a century later. Jaber, a major novelist and journalist who rarely gives interviews, once told me that, to him, such books are not historical novels, because “the world doesn’t change as much as we like to think. The same violence gets repeated,” including “arbitrary arrests though people are not guilty. This is our world. Though it may be imaginary to other people, to us it’s real.”

This absurd quality can loom larger in childhood memories, as in Lamia Ziadé’s graphic memoir that breaks the comics mold, Bye Bye Babylon: Beirut 1975-79 (2010; translated from French by Olivia Snaije in 2011), or the macabre surrealism of Mazen Maarouf’s Arabic short stories, Jokes for the Gunmen (2015; translated by Jonathan Wright in 2019). Both reveal a child’s-eye bewilderment at violence. But Ziadé’s wry commentary and vivid inventory of all that is gone, including cinemas and sweet shops (“I’ll remember it always”), contrasts with Maarouf’s darkly oblique take on lingering trauma. His Beirut—though transformed on the surface—is haunted by repressed memories. In one story, a man “unable to smile” stops the heart of a homeless person “who lived under a bridge that had acquired a bad reputation in the war” simply by announcing himself as the angel of death.

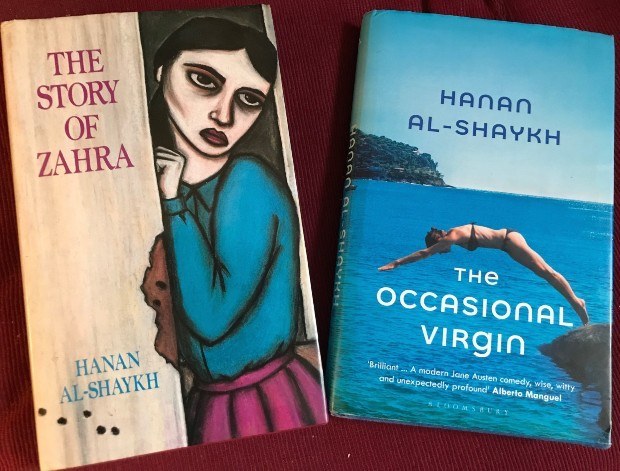

By ossifying religious identities, the civil war also stymied women’s rights. The memory of a sniper terrorizing her Beirut neighborhood on the Green Line was the trigger for Hanan Al-Shaykh’s influential Arabic classic The Story of Zahra (1980; translated by Peter Ford in 1986)—a novel that shocked many readers (including the nine publishers who turned it down) by refusing to take sides in what Al-Shaykh saw as a “men’s war.” A prominent journalist when war broke out—and recognized as a founding rebel in a special issue of Banipal magazine last year—she once told me that “there were two wars happening: the civil war, and the one fought all the time with family and traditions.” Her self-harming antiheroine, Zahra, experiences rape, back-street abortions, and electroconvulsive therapy at the hands of men in peacetime before finding sexual pleasure with a stranger she suspects is a rooftop sniper. Written forty years ago in London, the novel was groundbreaking not only in its richly colloquial language and sexual frankness, but for its insight into how warlords of all stripes mirrored the power of fathers and clerics.

Writer Hanan Al-Shaykh: “There were two wars happening: the civil war, and the one fought with family and traditions.”

Decades after the ambiguous liberation Zahra seized in wartime—and despite Beirut being one of the Arab world’s freest cities—women still grapple with straitjacketing notions of femininity and honor. Al-Shaykh revisits these themes with scathing humor in her novel The Occasional Virgin (2015; translated by Catherine Cobham in 2018), whose protagonists are Lebanese women in the diaspora. In Alexandra Chreiteh’s Always Coca-Cola (2009; translated by Michelle Hartman in 2012), the main characters are Beiruti women in their twenties—a generation steeped in global brands, and for whom the Israel-Hezbollah war of 2006 looms larger than the civil war. Yet they face many similar constraints to their mothers and grandmothers. Women’s rights have been held back, not simply by custom or religion, but by a sclerotic confessional system that enforces archaic laws—such as that preventing mothers from passing their nationality to their children. Women’s freedom has been a potent rallying cry in the recent protests alongside the icon of the “kick queen”—a viral image of a protester’s defensive kick at the groin of a politician’s bodyguard.

First edition of Hanan Al-Shaykh’s wartime classic The Story of Zahra in English translation (Peter Ford; Quartet Books, 1986) and her latest novel, The Occasional Virgin (Catherine Cobham; Bloomsbury, 2018). Copyright © Maya Jaggi.

If the collapse of the nation-state reinvented the Lebanese novel, its reconstitution could galvanize literature. Eddé commends young historians charting the civil war one day at a time, striving to encompass multiple memories and points of view—rather as fiction has done. But as she wrote in Le Monde before last December’s intensifying crackdown, Lebanon could face “much suffering” at the hands of a “vicious circle of manipulators” before the sectarian system falls or a consensus on history is reached.

“You agree on history when you create a secular democratic state,” Khoury said. His words to me as dusk fell on Achrafieh carried both warning and hope: “Every community here has its memory. When we arrive at a collective memory of the war, we’ll have a country.” In massing together as individuals under the Lebanese flag, the protesters not only proclaimed the end of the civil war. They also brought the prospect of a shared memory—and a new literary chapter—a step closer.

© 2020 by Maya Jaggi. All rights reserved.