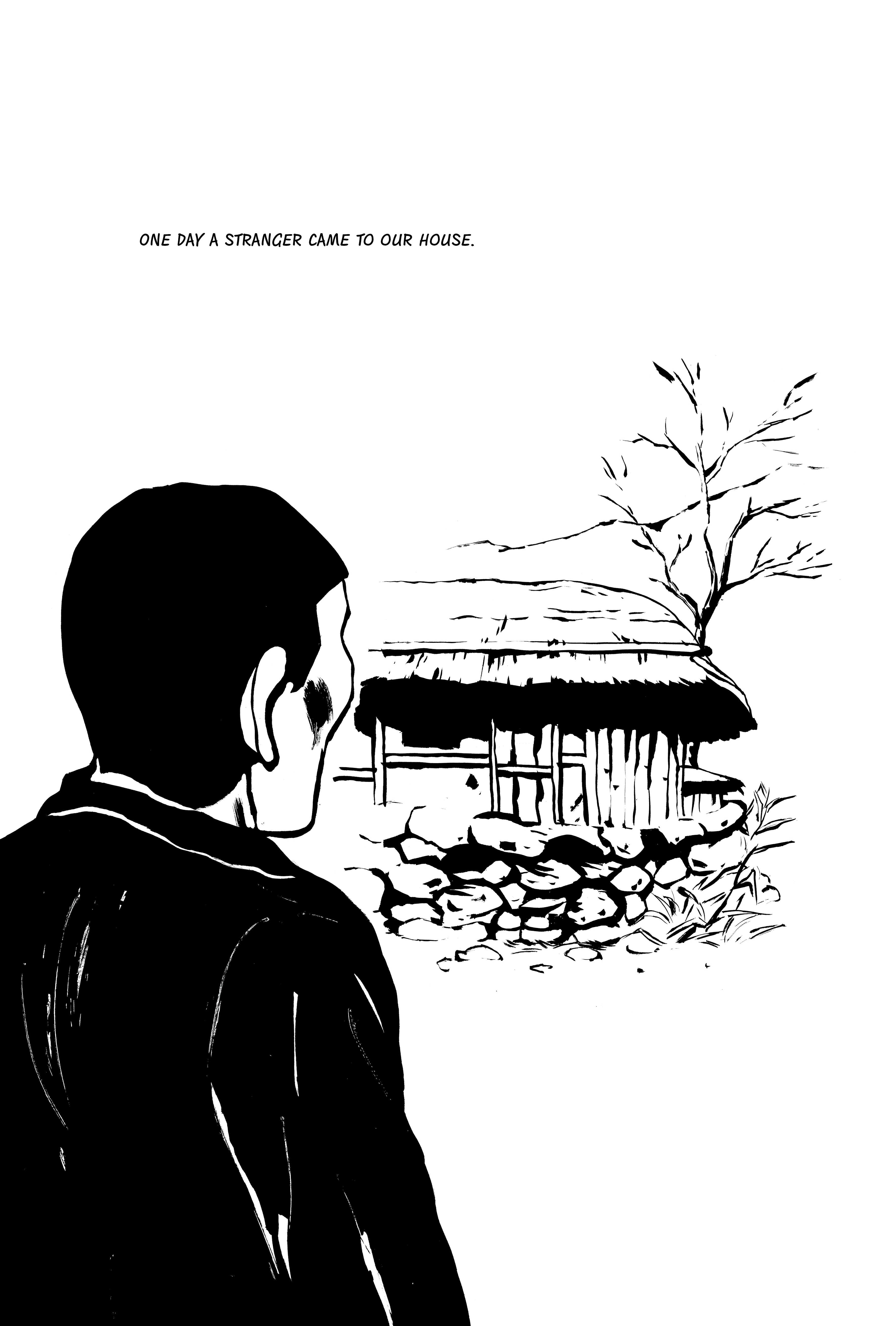

(Black-and-white drawing of a small house with a large figure of a man standing in front of it. His back is turned to viewers.) NARRATION: One day a stranger came to our house.

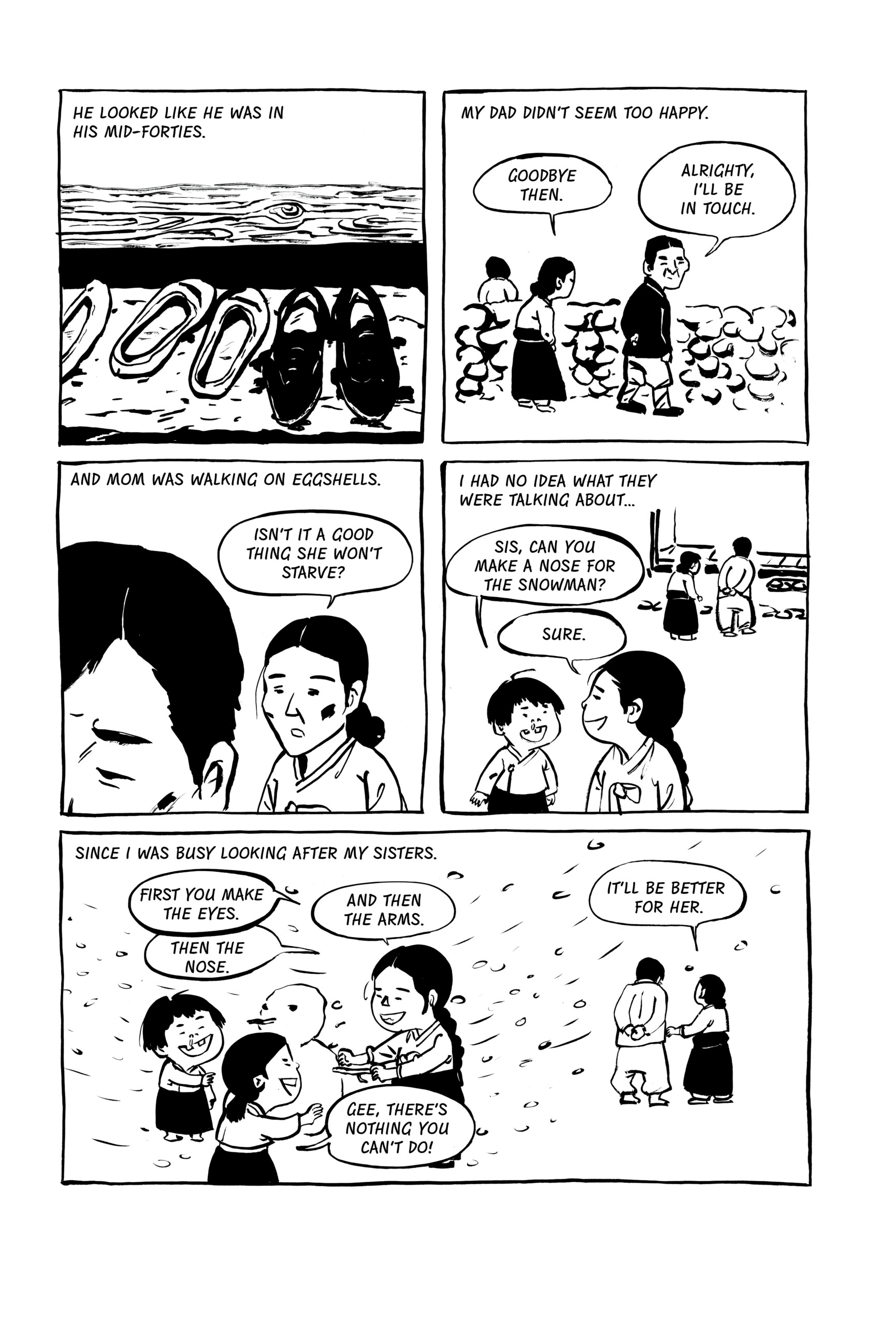

(Panel 1: An image of shoes. Panel 2: The stranger walks away from Mother, who is standing by a stone wall. Panel 3: Mother speaks to Father, whose back is turned to her. Panel 4: Ok-sun and Okja talk to each other while Mother and Father talk in the background. Panel 5: Ok-sun, Okja, and Okhui build a snowman together while Mother and Father talk in the background.) NARRATION: He looked like he was in his mid-forties. My dad didn't seem too happy. MOTHER: Goodbye then. STRANGER: Alrighty, I'll be in touch. NARRATION: And Mom was walking on eggshells. MOTHER (to FATHER): Isn't it a good thing she won't starve? NARRATION: I had no idea what they were talking about . . . OKJA (SISTER): Sis, can you make a nose for the snowman? OK-SUN (OLDER SISTER, NARRATOR): Sure. NARRATION: Since I was busy looking after my sisters. OK-SUN: First you make the eyes. Then the nose. And then the arms. OKHUI (SISTER): Gee, there's nothing you can't do! MOTHER (to FATHER): It'll be better for her.

(Panel 1: Mother speaks. Panel 2: Ok-sun looks over her shoulder. Panel 3: Ok-sun stands in the snow with her back to the viewer. Panel 4: A speech bubble emerges from inside a house. Panel 5: Mother and Ok-sun sit on the floor talking. Panel 6: Mother and Ok-sun continue talking, while Father sits in shadow in the background.) MOTHER (to OK-SUN): Ok-sun! Come in here for a minute. MOTHER: How'd you like to be adopted? OK-SUN: Adopted? MOTHER: There's an udon shop in Busan. MOTHER: The owners don't have any children, and they'd like to adopt you. What do you think?

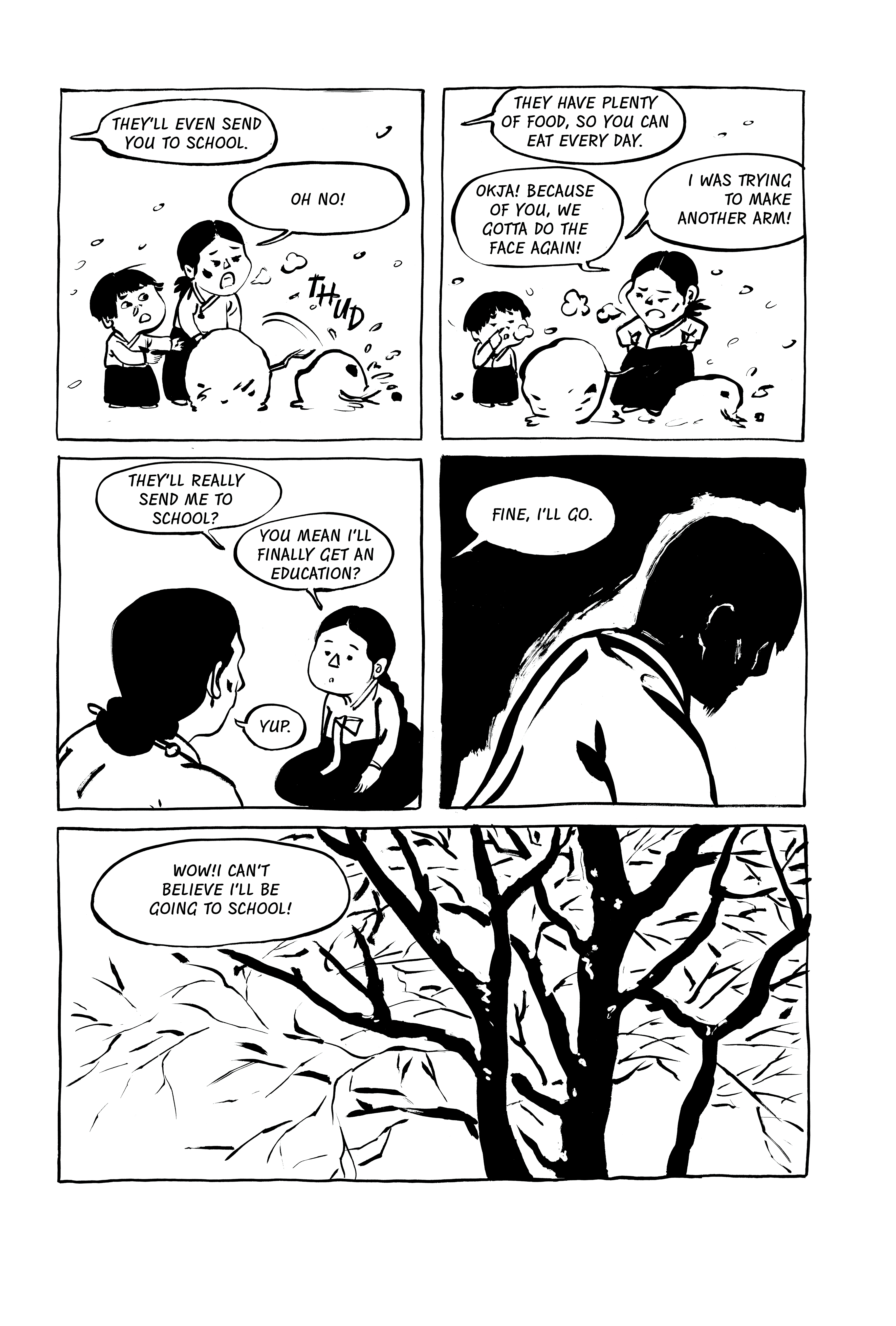

(Panel 1: Okhui and Okja look concerned as the head falls off a snowman. Panel 2: The girls argue as they look at the ruins of the snowman. Panel 3: Ok-sun speaks to Mother, whose back is turned to the viewer. Panel 4: Father stands with his face downcast and his head in shadow. Panel 5: A bare tree in winter.) MOTHER: They'll even send you to school. OKHUI: Oh no! MOTHER: They have plenty of food, so you can eat every day. OKHUI: Okja! Because of you, we gotta do the face again! OKJA: I was trying to make another arm! OK-SUN: They'll really send me to school? You mean I'll finally get an education? MOTHER: Yup. OK-SUN: Fine, I'll go. OK-SUN: Wow! I can't believe I'll be going to school!

(Panel 1: Ok-sun speaks while Father's legs are visible in the background. Panel 2: Mother looks concerned. Panel 3: Father, seated on the floor, holds a pipe in his mouth. Panel 4: Father smokes his pipe. Panel 5: Ok-sun grins and opens the door. Mother is visible in the background.) OK-SUN: But can I come home if I want? OK-SUN: This isn't goodbye forever, right? MOTHER: You come back any time. MOTHER: But don't waste this opportunity. Try to stick with it. Study hard and listen to your elders. OK-SUN: Am I dreaming? OK-SUN: Papa! I'm finally gonna go to school! OK-SUN: Okhui! Okja! I'm gonna go to school!

(Snow falls on a country landscape). NARRATION: I never should have said yes.

(Snow continues to fall on the country landscape from the previous page.) NARRATION: I had no idea I wouldn't be coming back. Never in my wildest dreams did I think I'd be saying goodbye forever.

(Panel 1: Mother and Ok-sun stand facing the stranger. Panel 2: Mother speaks to Ok-sun, who looks over her shoulder as she follows the stranger. Panel 3: The stranger walks away with his back to the viewer. Ok-sun follows, waving without looking back as Mother waves good-bye.) NARRATION: Early in the morning, while everyone was sleeping... MOTHER: Please look after our Ok-sun. STRANGER: Humph, I told you there's no need to worry. NARRATION: I left home. MOTHER: Take care of yourself. NARRATION: If I looked back... MOTHER: Make sure you listen to your elders. OK-SUN: Don't worry about me. I'm your daughter, ain't I? Ma, you just worry about yourself.

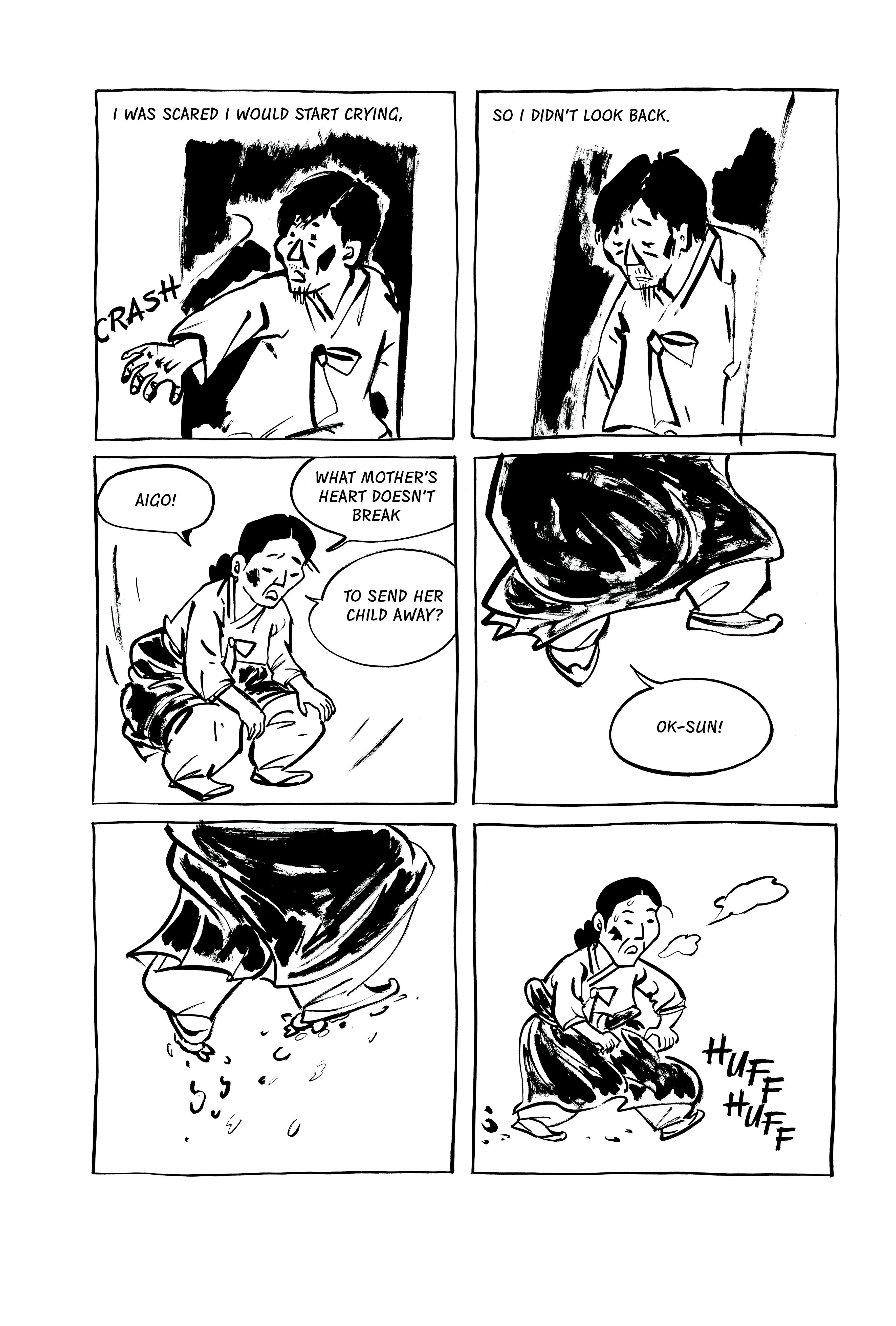

(Panel 1: Father stands in a doorway. Panel 2: He looks downcast. Panel 3: Mother crouches on the ground. Panel 4: Mother's legs appear alongside a speech bubble. Panel 5: Mother's feet walk through the snow. Panel 6: Mother breathes heavily.) NARRATION: I was scared I would start crying, so I didn't look back. MOTHER: Aigo! MOTHER: What mother's heart doesn't break to send her child away? MOTHER: Ok-sun!

(A tear rolls down Mother's cheek as she looks at the bare trees and the snow.) MOTHER: Ok-sun, my baby girl. At least you won't go hungry now.

(The small figures of Ok-sun and the stranger walking away are visible in the distance on a snowy hill.)