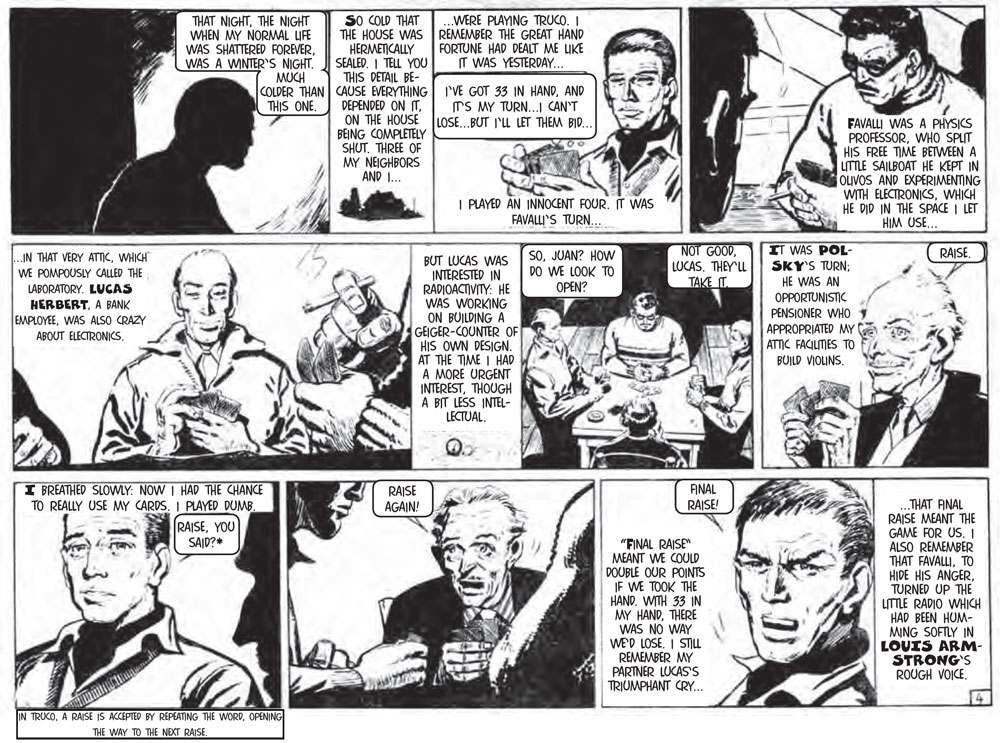

Man in shadow: THAT NIGHT , THE NIGHT WHEN MY NORMAL LIFE WAS SHATTERED FOREVER , WAS A WINTER'S NIGHT , MUCH COLDER THAN THIS ONE

SO COLD THAT THE HOUSE WAS HERMETICALLY SEALED . I TELL YOU THIS DETAIL BE CAUSE EVERYTHING DEPENDED ON IT . ON THE HOUSE BEING COMPLETELY SHUT THREE OF MY NEIGHBORS AND I ...

WERE PLAYING TRUCO . I REMEMBER THE GREAT HAND FORTUNE HAD DEALT ME LIKE IT WAS YESTERDAY ....

Juan to himself: I'VE GOT 33 IN HAND , AND IT'S MY TURN ... I CAN'T LOSE ... BUT I'LL LET THEM BID ..

I PLAYED AN INNOCENT FOUR . IT WAS FAVALLI'S TURN ...

FAVALLI WAS A PHYSICS PROFESSOR , WHO SPUIT HIS FREE TIME BETWEEN A LITTLE SAILBOAT HE KEPT IN OLIVOS AND EXPERIMENTING WITH ELECTRONICS , WHICH HE DID IN THE SPACE I LET HIM USE ..

..IN THAT VERY ATTIC , WHICH WE POMPOUSLY CALLED THE LABORATORY . LUCAS HERBERT , A BANK EMPLOYEE , WAS ALSO CRAZY ABOUT ELECTRONICS .

BUT LUCAS WAS INTERESTED IN RADIOACTIVITY : HE IWAS WORKING ON BUILDING A GEIGER - COUNTER OF HIS OWN DESIGN . AT THE TIME I HAD A MORE URGENT INTEREST , THOUGH A BIT LESS INTEL LECTUAL .

Lucas Herbert: SO , JUAN ? HOW DO WE LOOK TO OPEN ?

Juan: NOT GOOD , LUCAS . THEY'LL TAKE IT .

IT WAS POLSKY'S TURN ; HE WAS AN OPPORTUNISTIC PENSIONER WHO APPROPRIATED MY ATTIC FACILIMES TO BUILD VIOLINS .

Polsky: RAISE

I BREATHED SLOWLY : NOW I HAD THE CHANCE TO REALLY USE MY CARDS . I PLAYED DUMB .

Juan: RAISE , YOU SAID ? *

TRUCO , A RAISE IS ACCEPTED BY REPEATING THE WORD , OPENING THE WAY TO THE NEXT RAISE .

Polsky: RAISE AGAIN !

" FINAL RAISE " MEANT WE COULD DOUBLE OUR POINTS IF WE TOOK THE HAND , WITH 33 IN MY HAND , THERE WAS NO WAY WE'D LOSE . I STILL REMEMBER MY PARTNER LUCAS'S TRIUMPHANT CRY ...

Juan: FINAL RAISE !

THAT FINAL RAISE MEANT THE GAME FOR US . I ALSO REMEMBER THAT FAVALLI , TO HIDE HIS ANGER , TURNED UP THE LITTLE RADIO WHICH HAD BEEN HUMMING SOFTLY IN LOUIS ARMSTRONG'S ROUGH VOICE .

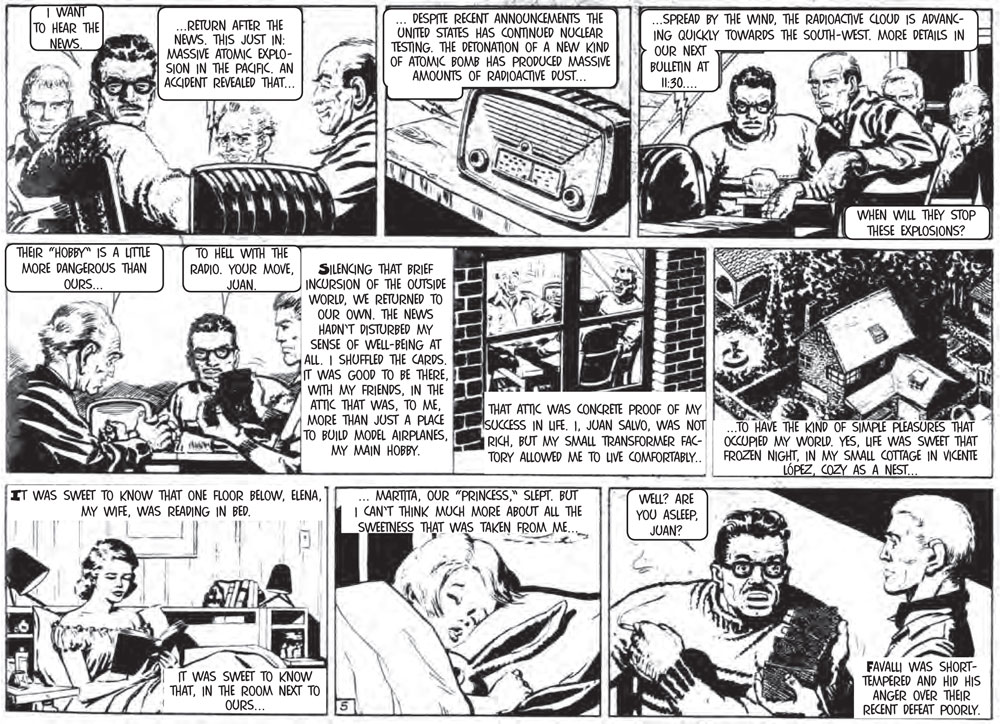

Favalli: I WANT TO HEAR THE NEWS .

Radio Broadcast: ... RETURN AFTER THE NEWS , THIS JUST IN : MASSIVE ATOMIC EXPLO SION IN THE PACIFIC . AN ACCIDENT REVEALED THAT ...

Radio Broadcast: ... DESPITE RECENT ANNOUNCEMENTS THE UNITED STATES HAS CONTINUED NUCLEAR TESTING . THE DETONATION OF A NEW KIND OF ATOMIC BOMB HAS PRODUCED MASSIVE AMOUNTS OF RADIOACTIVE DUST ...

Radio Broadcast: ... SPREAD BY THE WIND , THE RADIOACTIVE CLOUD IS ADVANC ING QUICKLY TOWARDS THE SOUTH - WEST . MORE DETAILS IN OUR NEXT BULLETIN AT 11:30 .

Polsky: WHEN WILL THEY STOP THESE EXPLOSIONS ?

Polsky: THEIR " HOBBY " IS A LITTLE MORE DANGEROUS THAN OURS .

Favalli: TO HELL WITH THE RADIO . YOUR MOVE , JUAN

SILENCING THAT BRIEF INCURSION OF THE OUTSIDE WORLD , WE RETURNED TO OUR OWN . THE NEWS HADN'T DISTURBED MY SENSE OF WELL - BEING AT ALL . I SHUFFLED THE CARDS . I WAS GOOD TO BE THERE , WITH MY FRIENDS , IN THE ATTIC THAT WAS , TO ME , MORE THAN JUST A PLACE TO BUILD MODEL AIRPLANES , MY MAIN HOBBY . HHH .

THAT ATTIC WAS CONCRETE PROOF OF MY SUCCESS IN LIFE . I , JUAN SALVO , WAS NOT RICH , BUT MY SMALL TRANSFORMER FACTORY ALLOWED ME TO LIVE COMFORTABLY ..

... TO HAVE THE KIND OF SIMPLE PLEASURES THAT OCCUPIED MY WORLD . YES , LIFE WAS SWEET THAT FROZEN NIGHT , IN MY SMALL COTTAGE IN VICENTE LÓPEZ , COZY AS A NEST .

IT WAS SWEET TO KNOW THAT ONE FLOOR BELOW , ELENA , MY WIFE , WAS READING IN BED .

IT WAS SWEET TO KNOW THAT , IN THE ROOM NEXT TO OURS ..

... MARTITA , OUR " PRINCESS , " SLEPT . BUT I CAN'T THINK MUCH MORE ABOUT ALL THE SWEETNESS THAT WAS TAKEN FROM ME .

Favalli: WELL ? ARE YOU ASLEEP , JUAN ?

FAVALLI WAS SHORT TEMPERED AND HID HIS ANGER OVER THEIR RECENT DEFEAT POORLY .

Juan: OK , OK , FAVA ..

I BEGAN TO DEAL , STILL ENJOYING THE MOMENT .

THE FOUR OF US IN THAT WARM ATTIC , MORE THAN MADE UP FOR THE COLDNESS OUTSIDE , WITHERING THE PLANTS IN THE GARDEN .

WE WERE APART FROM THE WORLD , AS THOUGH THE LITTLE COTTAGE WERE AN IS AN ISLAND BARELY TOUCHED BY THE NOISE OF THE NEARBY STREETS ... LAND

THE WHINING CLUTCH OF A BUS , THE STEPS OF A COUPLE FLEEING THE COLD , THE SWIFT PASSING OF A CAR MAKING THE MOST OF THE LIGHT TRAFFIC ..

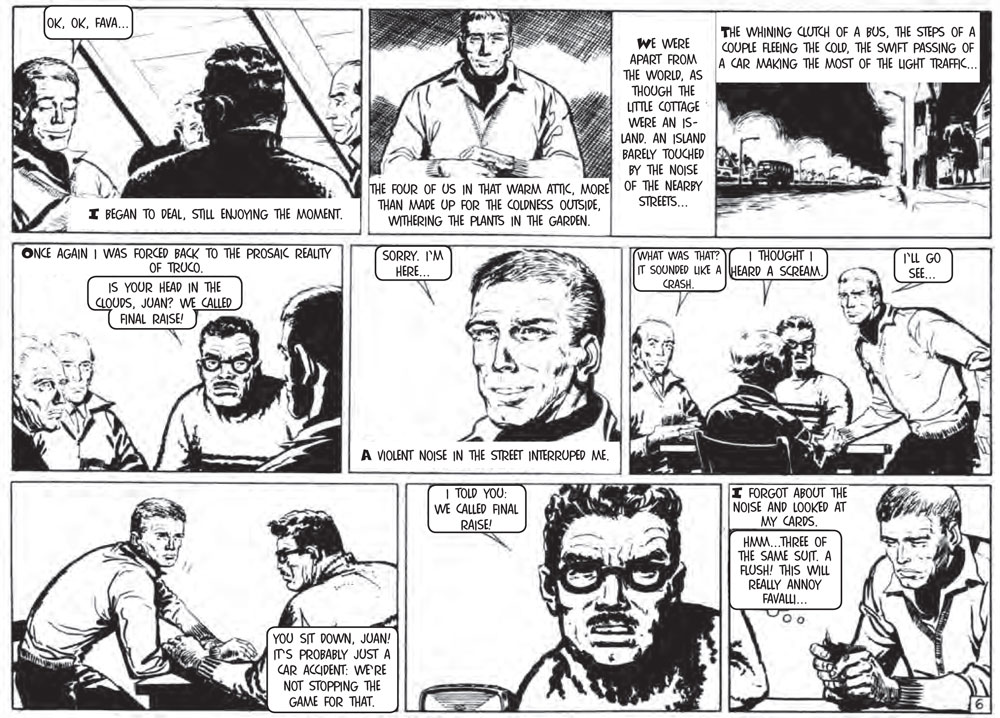

ONCE AGAIN I WAS FORCED BACK TO THE PROSAIC REALITY OF TRUCO .

Favalli: IS YOUR HEAD IN THE CLOUDS , JUAN ? WE CALLED FINAL RAISE !

Juan: SORRY . I'M HERE ,

A VIOLENT NOISE IN THE STREET INTERRUPED ME .

Lucas: WHAT WAS THAT ? IT SOUNDED LIKE A CRASH .

Favalli: I THOUGHT I HEARD A SCREAM .

Juan: I'LL GO SEE

Favalli: YOU SIT DOWN , JUAN ! IT'S PROBABLY JUST A CAR ACCIDENT : WE'RE NOT STOPPING THE GAME FOR THAT .

Favalli: I TOLD YOU : WE CALLED FINAL RAISE !

I FORGOT ABOUT THE NOISE AND LOOKED AT MY CARDS .

Juan: HMM ... THREE OF THE SAME SUIT . A FLUSH ! THIS WILL REALLY ANNOY FAVALLI ..

VICTORY ASSURED , I SUNG A FAMILIAR SONG TO MYSELF ..

Juan: POR EL RÍO PARANÁ ..

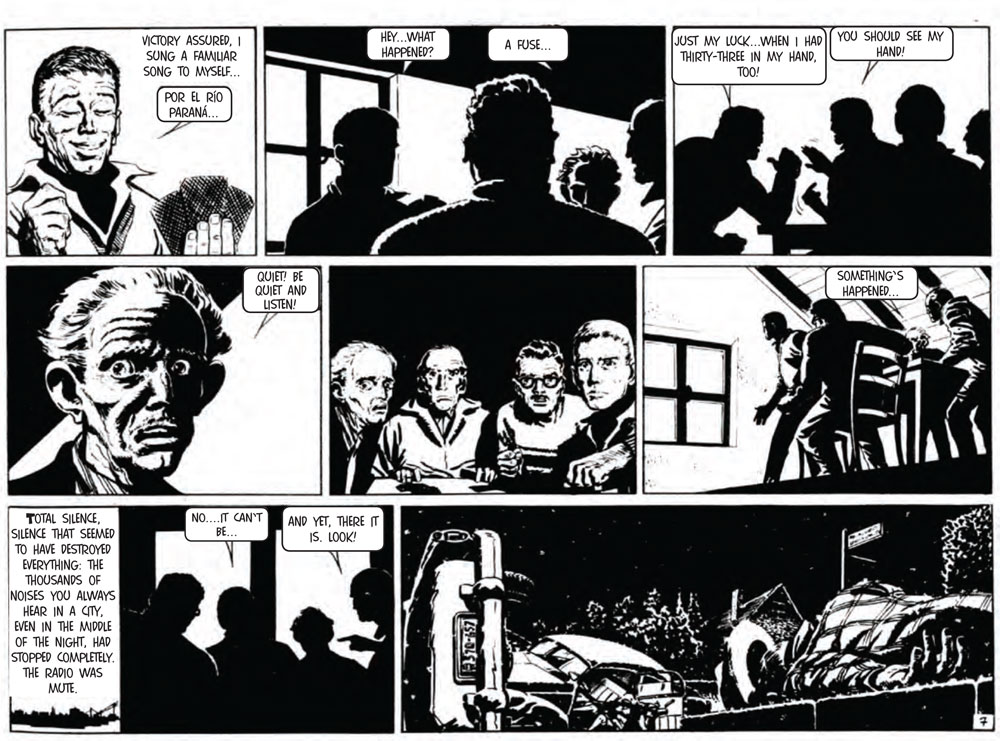

Juan: HEY ... WHAT HAPPENED ?

Lucas: A FUSE ..

Favalli: JUST MY LUCK .... WHEN I HAD THIRTY - THREE IN MY HAND , TOO !

Juan: YOU SHOULD SEE MY HAND !

Polsky: QUIET ! BE QUIET AND LISTEN !

Polsky: SOMETHING'S HAPPENED .

TOTAL SILENCE , SILENCE THAT SEEMED TO HAVE DESTROYED EVERYTHING : THE THOUSANDS OF NOISES YOU ALWAYS HEAR IN A CITY , EVEN IN THE MIDDLE OF THE NIGHT , HAD STOPPED COMPLETELY . THE RADIO WAS MUTE

Juan: NO .... IT CAN'T BE ...

Lucas: AND YET , THERE IT IS . LOOK !

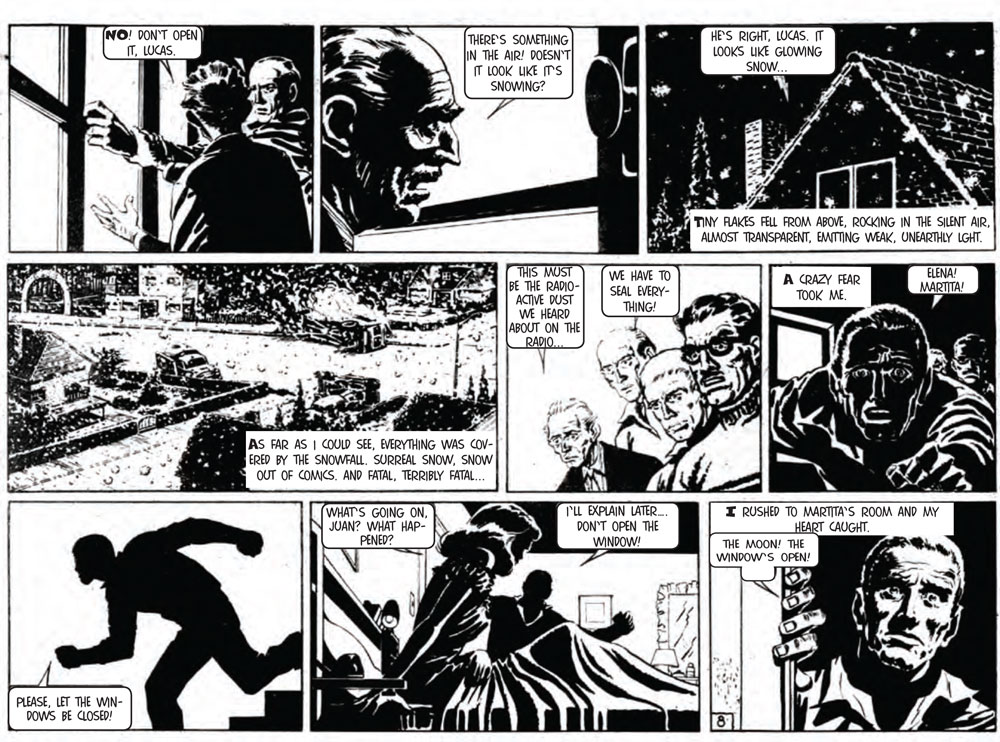

Polsky: NO ! DON'T OPEN IT . LUCAS ,

Polsky: THERE'S SOMETHING IN THE AIR ! DOESN'T IT LOOK LIKE IT'S SNOWING ?

Favalli: HE'S RIGHT , LUCAS . IT LOOKS LIKE GLOWING SNOW ..

TINY FLAKES FELL FROM ABOVE , ROCKING IN THE SILENT AIR , ALMOST TRANSPARENT , EMITTING WEAK , UNEARTHLY LGHT .

AS FAR AS I COULD SEE , EVERYTHING WAS COVERED BY THE SNOWFALL . SURREAL SNOW , SNOW OUT OF COMICS . AND FATAL , TERRIBLY FATAL ...

Polsky: THIS MUST BE THE RADIO ACTIVE DUST WE HEARD ABOUT ON THE RADIO ..

Lucas: WE HAVE TO SEAL EVERY THING !

A CRAZY FEAR TOOK ME .

Juan: ELENA ! MARTITA !

Juan: PLEASE , LET THE WINDOWS BE CLOSED !

Elena: WHAT'S GOING ON , JUAN ? WHAT HAPPENED ?

Juan: I'LL EXPLAIN LATER ..... DON'T OPEN THE WINDOW !

I RUSHED TO MARTITA'S ROOM AND MY HEART CAUGHT .

Juan: THE MOON ! THE WINDOW'S OPEN !

Juan: NO...WE LEFT THE CURTAINS OPEN , BUT THE WINDOW'S CLOSED .

I COULDN'T DO ANYTHING BUT HUG MY DAUGHTER , SQUEEZE HER ...

Martita: TOO TIGHT , PAPA !

Elena: WHAT'S HAPPENED , JUAN ? TELL ME !

Juan: SOMETHING HAPPENED OUTSIDE , SOMETHING TERRIBLE EVERYONE IN THE STREETS IS DEAD ..

Juan: FAVALLI SAYS IT MUST BE BECAUSE OF THE FLAKES ... I THINK THEY'RE RADIOACTIVE . WE HAVE TO KEEP EVERYTHING SEALED SO NOTHING CAN GET IN !

FROM THE OTHER ROOMS , WE HEARD THE PANICKED VOICES OF MY THREE FRIENDS . FAVALLI ASKED FOR PUTTY TO SEAL ANY OPENINGS ; POLSKY TRIED TO USE THE PHONE . LUCAS PACED BACK AND FORTH .

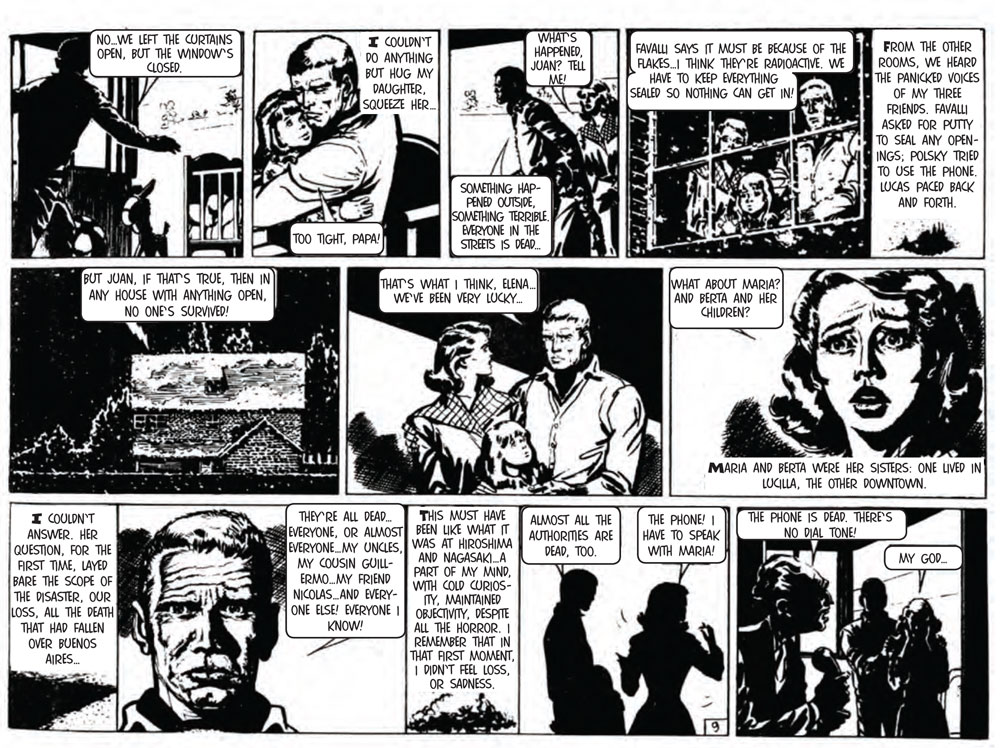

Elena: BUT JUAN , IF THAT'S TRUE , THEN IN ANY HOUSE WITH ANYTHING OPEN , NO ONE'S SURVIVED !

Juan: THAT'S WHAT I THINK , ELENA .. WE'VE BEEN VERY LUCKY ...

Elena: WHAT ABOUT MARIA ? AND BERTA AND HER CHILDREN ?

MARIA AND BERTA WERE HER SISTERS : ONE LIVED IN LUCILLA , THE OTHER DOWNTOWN .

I COULDN'T ANSWER . HER QUESTION , FOR THE FIRST TIME , LAYED BARE THE SCOPE OF THE DISASTER , OUR LOSS , ALL THE DEATH THAT HAD FALLEN OVER BUENOS AIRES ...

Juan: HEY'RE ALL DEAD .... EVERYONE , OR ALMOST EVERYONE MY UNCLES , MY COUSIN GUILLERMO ... MY FRIEND NICOLAS AND EVERY ONE ELSE ! EVERYONE I KNOW !

THIS MUST HAVE BEEN LIKE WHAT IT WAS AT HIROSHIMA AND NAGASAKIA PART OF MY MIND , WITH COLD CURIOSITY , MAINTAINED OBJECTIVITY , DESPITE ALL THE HORROR . I REMEMBER THAT IN THAT FIRST MOMENT , I DIDN'T FEEL LOSS , OR SADNESS ,

Juan: ALMOST ALL THE AUTHORITIES ARE DEAD , TOO .

Elena: THE PHONE ! I HAVE TO SPEAK WITH MARIA !

Polsky: THE PHONE IS DEAD . THERE'S NO DIAL TONE !

Elena: MY GOD...

Elena: MY GOD !

Juan: STAY CALM , ELENA . WE CAN'T AFFORD TO LOSE OUR HEADS ... WE'RE ALL IN DANGER .

Elena: MAYBE IT'S NOT AS BAD AS IT LOOKS ...

THE HUMAN MIND IS ABSURD . I REMEMBER THINKING ABOUT THE NATIONAL SOCCER TEAM . COULD THEY ALL BE DEAD ? COULD A SINGLE BLOW HAVE WIPED OUT THE WHOLE TEAM ? I SHOOK MY HEAD . I THINK MY MIND ....

FOCUSED ON THESE THINGS SO AS NOT TO GO MAD .

Elena: YOU HAVE TO SEAL EVERY THING , JUAN !

Juan: FAVALLI'S ALREADY DOING IT . IT'S LUCKY THEY WERE HERE .

IN THAT MOMENT ....

..WE HEARD A DISTORTED VOICE ...

Polsky: THE PHONE IS DEAD

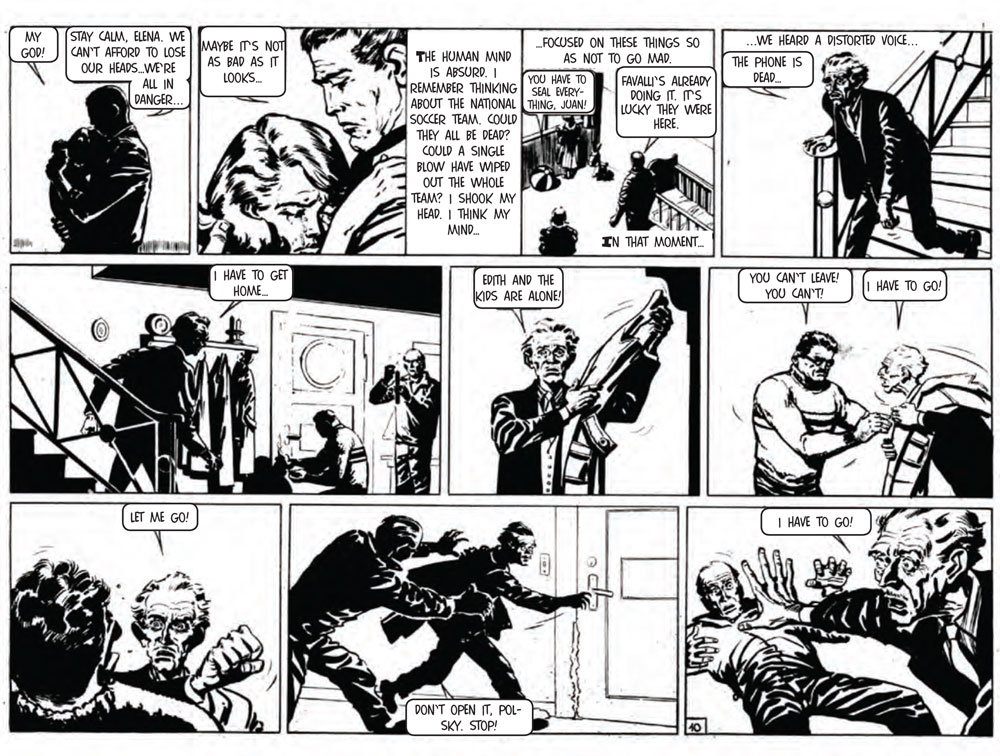

Polsky: I HAVE TO GET HOME

Polsky: EDITH AND THE KIDS ARE ALONE !

Favalli: YOU CAN'T LEAVE ! YOU CAN'T !

Polsky: I HAVE TO GO !

Polsky: LET ME GO !

Lucas: DON'T OPEN IT , POLSKY . STOP !

Polsky: I HAVE TO GO !

Polsky: EDITH . THE KIDS ....

Favalli: CLOSE THE DOOR , LUCAS ! NOW !

THE SLAM SHOOK THE WHOLE HOUSE .

IT HAPPENED SO FAST , AND I WAS SO SHOCKED , THAT I COULDN'T INTER VENE . THEN AGAIN , I WOULDN'T HAVE BEEN IN TIME TO STOP HIM .

IT WAS ELENA WHO SAW WHAT HAPPENED ....

Elena: LOOK , JUAN ! POLSKY LEFT !

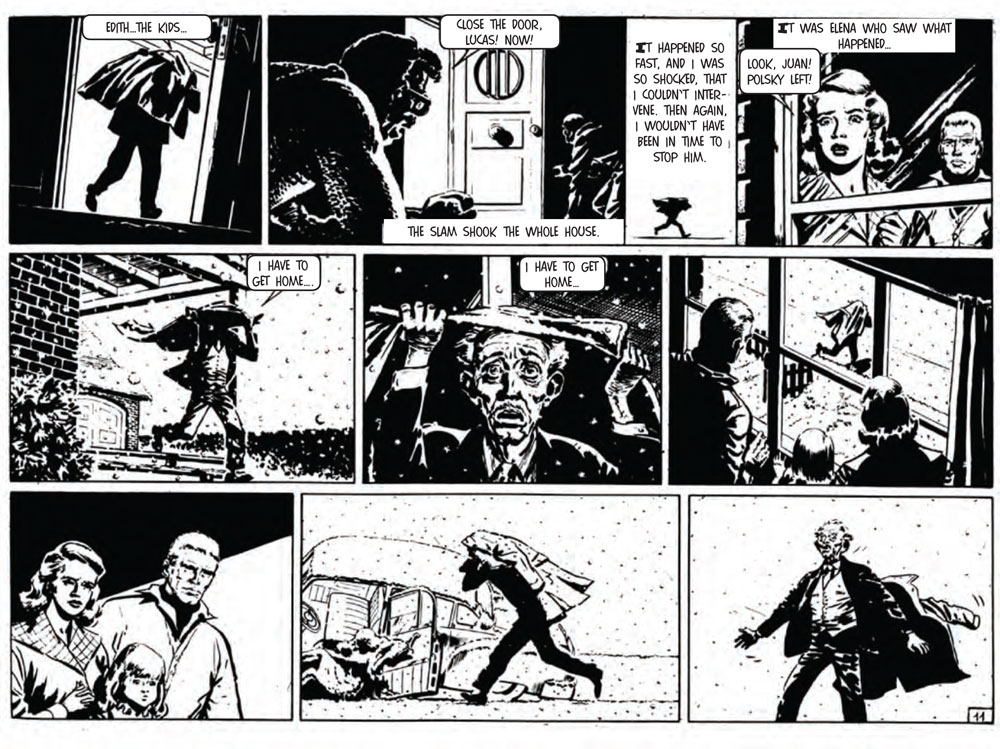

Polsky: I HAVE TO GET HOME ...

Polsky: I HAVE TO GET HOME ...

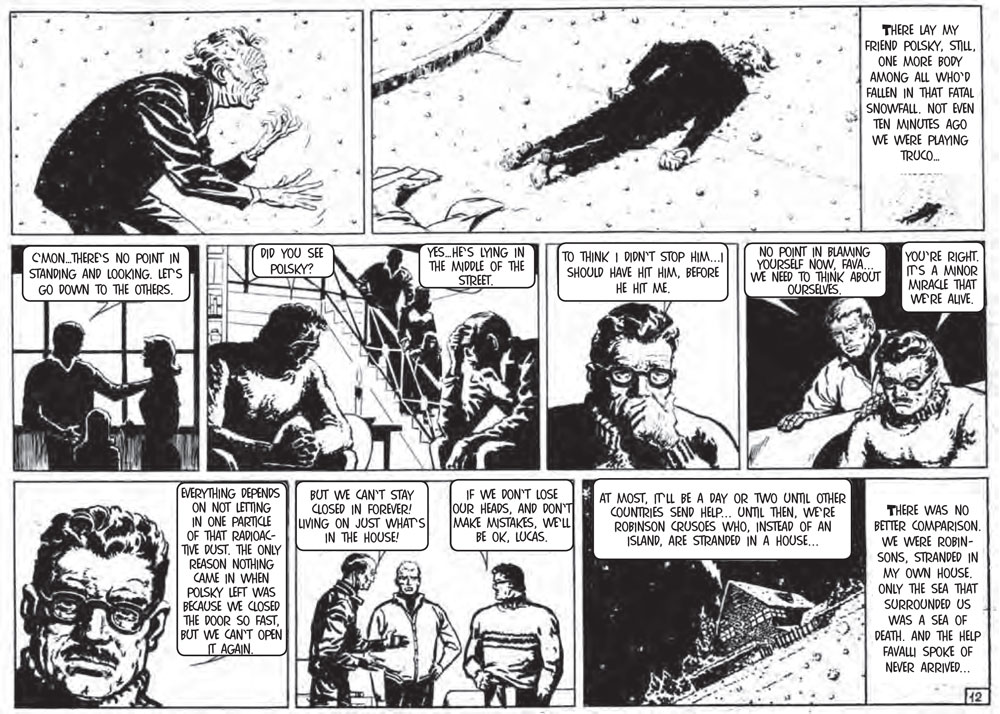

THERE LAY MY FRIEND POLSKY , STILL , ONE MORE BODY AMONG ALL WHO'D FALLEN IN THAT FATAL SNOWFALL . NOT EVEN TEN MINUTES AGO WE WERE PLAYING TRUCO ...

Juan: CMON . THERE'S NO POINT IN STANDING AND LOOKING . LET'S GO DOWN TO THE OTHERS .

Favalli: DID YOU SEE POLSKY ?

Juan: YES . HE'S LYING IN THE MIDDLE OF THE STREET .

Favalli: TO THINK I DIDN'T STOP HIM .. SHOULD HAVE HIT HIM , BEFORE HE HIT ME .

Juan: NO POINT IN BLAMING YOURSELF NOW , FAVA . WE NEED TO THINK ABOUT OURSELVES .

Favalli: YOU'RE RIGHT . IT'S A MINOR MIRACLE THAT WE'RE ALIVE .

Favalli: EVERYTHING DEPENDS ON NOT LETTING IN ONE PARTICLE OF THAT RADIOACTIVE DUST . THE ONLY REASON NOTHING CAME IN WHEN POLSKY LEFT WAS BECAUSE WE CLOSED THE DOOR SO FAST , BUT WE CAN'T OPEN IT AGAIN .

Lucas: BUT WE CAN'T STAY CLOSED IN FOREVER ! LIVING ON JUST WHAT'S IN THE HOUSE !

Favalli: IF WE DON'T LOSE OUR HEADS , AND DON'T MAKE MISTAKES , WE'LL BE OK , LUCAS ,

Favalli: AT MOST , IT'LL BE A DAY OR TWO UNTIL OTHER COUNTRIES SEND HELP ... UNTIL THEN , WE'RE ROBINSON CRUSOES WHO , INSTEAD OF AN ISLAND , ARE STRANDED IN A HOUSE ...

THERE WAS NO BETTER COMPARISON . WE WERE ROBINSONS , STRANDED IN MY OWN HOUSE . ONLY THE SEA THAT SURROUNDED US WAS A SEA OF DEATH . AND THE HELP FAVALLI SPOKE OF NEVER ARRIVED ...

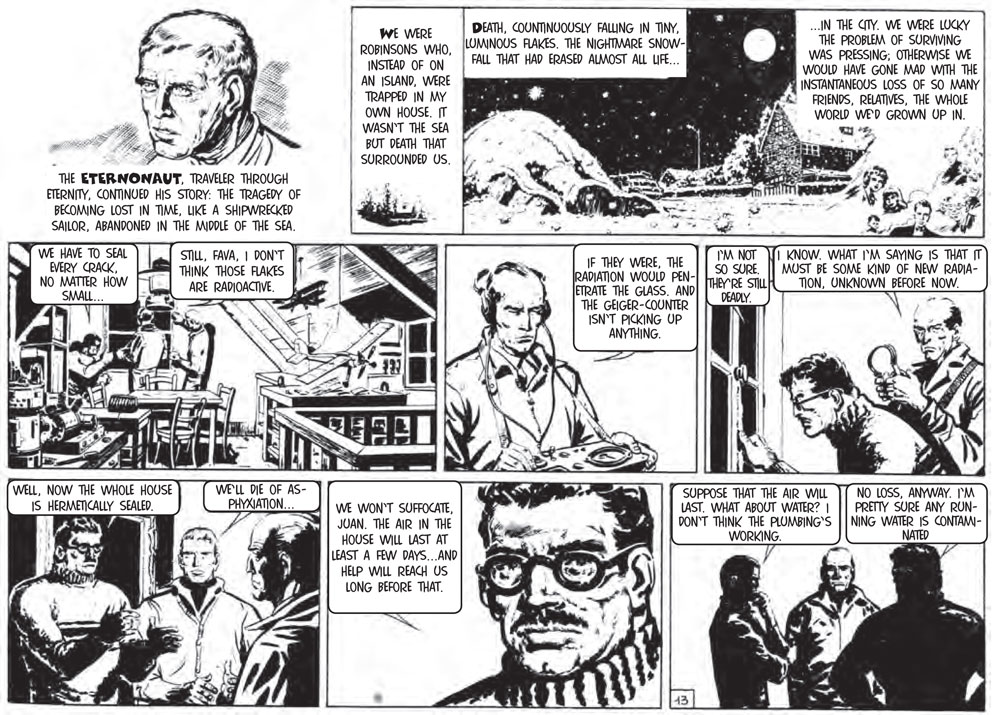

THE ETERNONAUT , TRAVELER THROUGH ETERNITY , CONTINUED HIS STORY : THE TRAGEDY OF BECOMING LOST IN TIME , LIKE A SHIPWRECKED SAILOR , ABANDONED IN THE MIDDLE THE SEA .

WE WERE ROBINSONS WHO , INSTEAD OF ON AN ISLAND , WERE TRAPPED IN MY OWN HOUSE . IT WASN'T THE SEA BUT DEATH THAT SURROUNDED US .

DEATH , COUNTINUOUSLY FALLING IN TINY , LUMINOUS FLAKES . THE NIGHTMARE SNOW FALL THAT HAD ERASED ALMOST ALL LIFE ...

... IN THE CITY . WE WERE LUCKY THE PROBLEM OF SURVIVING WAS PRESSING ; OTHERWISE WE WOULD HAVE GONE MAD WITH THE INSTANTANEOUS LOSS OF SO MANY FRIENDS , RELATIVES , THE WHOLE WORLD WE'D GROWN UP IN .

Favalli: WE HAVE TO SEAL EVERY CRACK . NO MATTER HOW SMALL...

Lucas: STILL , FAVA , I DON'T THINK THOSE FLAKES ARE RADIOACTIVE .

Lucas: IF THEY WERE , THE RADIATION WOULD PENETRATE THE GLASS . AND THE GEIGER - COUNTER ISN'T PICKING UP ANYTHING .

Favalli: I'M NOT SO SURE THEY'RE STILL DEADLY .

Lucas: I KNOW . WHAT I'M SAYING IS THAT IT MUST BE SOME KIND OF NEW RADIATION , UNKNOWN BEFORE NOW .

Favalli: WELL , NOW THE WHOLE HOUSE IS HERMETICALLY SEALED .

Juan: WE'LL DIE OF AS PHYXIATION .

Favalli: WE WON'T SUFFOCATE , JUAN . THE AIR IN THE HOUSE WILL LAST AT LEAST A FEW DAYS ... AND HELP WILL REACH US LONG BEFORE THAT .

Juan: SUPPOSE THAT THE AIR WILL LAST . WHAT ABOUT WATER ? I DON'T THINK THE PLUMBING'S WORKING .

Favalli: NO LOSS , ANYWAY . I'M PRETTY SURE ANY RUNNING WATER IS CONTAMINATED

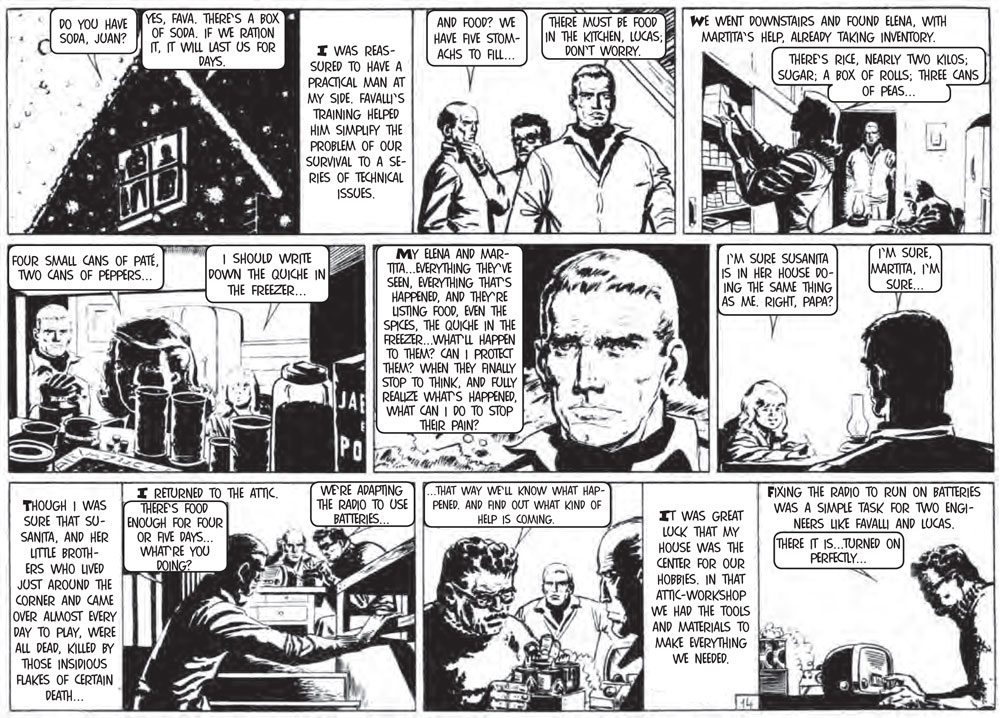

Favalli: DO YOU HAVE SODA , JUAN ?

Juan: YES , FAVA . THERE'S A BOX OF SODA . IF WE RATION IT , IT WILL LAST US FOR DAYS .

I WAS REASSURED TO HAVE A PRACTICAL MAN AT MY SIDE . FAVALLI'S TRAINING HELPED HIM SIMPLIFY THE PROBLEM OF OUR SURVIVAL TO A SERIES OF TECHNICAL ISSUES .

Lucas: AND FOOD ? WE HAVE FIVE STOMACHS TO FILL ...

Juan: THERE MUST BE FOOD IN THE KITCHEN , LUCAS ; DON'T WORRY

WE WENT DOWNSTAIRS AND FOUND ELENA , WITH MARTITA'S HELP , ALREADY TAKING INVENTORY .

Elena: THERE'S RICE , NEARLY TWO KILOS ; SUGAR ; A BOX OF ROLLS ; THREE CANS OF PEAS ...

Elena: FOUR SMALL CANS OF PATÉ , TWO CANS OF PEPPERS ...

Martita: I SHOULD WRITE DOWN THE QUICHE IN THE FREEZER ...

MY ELENA AND MARTITA ... EVERYTHING THEY'VE SEEN , EVERYTHING THAT'S HAPPENED , AND THEY'RE LISTING FOOD , EVEN THE SPICES , THE QUICHE IN THE FREEZER ... WHAT'LL HAPPEN TO THEM ? CAN I PROTECT THEM ? WHEN THEY FINALLY STOP TO THINK , AND FULLY REALIZE WHAT'S HAPPENED , WHAT CAN I DO TO STOP THEIR PAIN ?

Martita: I'M SURE SUSANITA IS IN HER HOUSE DOING THE SAME THING AS ME . RIGHT , PAPA ?

Juan: I'M SURE , MARTITA , IM SURE...

THOUGH I WAS SURE THAT SUSANITA , AND HER LITTLE BROTHERS WHO LIVED JUST AROUND THE CORNER AND CAME OVER ALMOST EVERY DAY TO PLAY , WERE ALL DEAD , KILLED BY THOSE INSIDIOUS FLAKES OF CERTAIN DEATH ...

I RETURNED TO THE ATTIC .

Juan: THERE'S FOOD ENOUGH FOR FOUR OR FIVE DAYS . WHAT'RE YOU DOING ?

Favalli: WE'RE ADAPTING THE RADIO TO USE BATTERIES ...

Favalli: ... THAT WAY WELL KNOW WHAT HAPPENED , AND FIND OUT WHAT KIND OF HELP IS COMING .

IT WAS GREAT LUCK THAT MY HOUSE WAS THE CENTER FOR OUR HOBBIES . IN THAT ATTIC - WORKSHOP WE HAD THE TOOLS AND MATERIALS TO MAKE EVERYTHING WE NEEDED .

FIXING THE RADIO TO RUN ON BATTERIES WAS A SIMPLE TASK FOR TWO ENGINEERS LIKE FAVALLI AND LUCAS .

Favalli: THERE IT IS ... TURNED ON PERFECTLY .

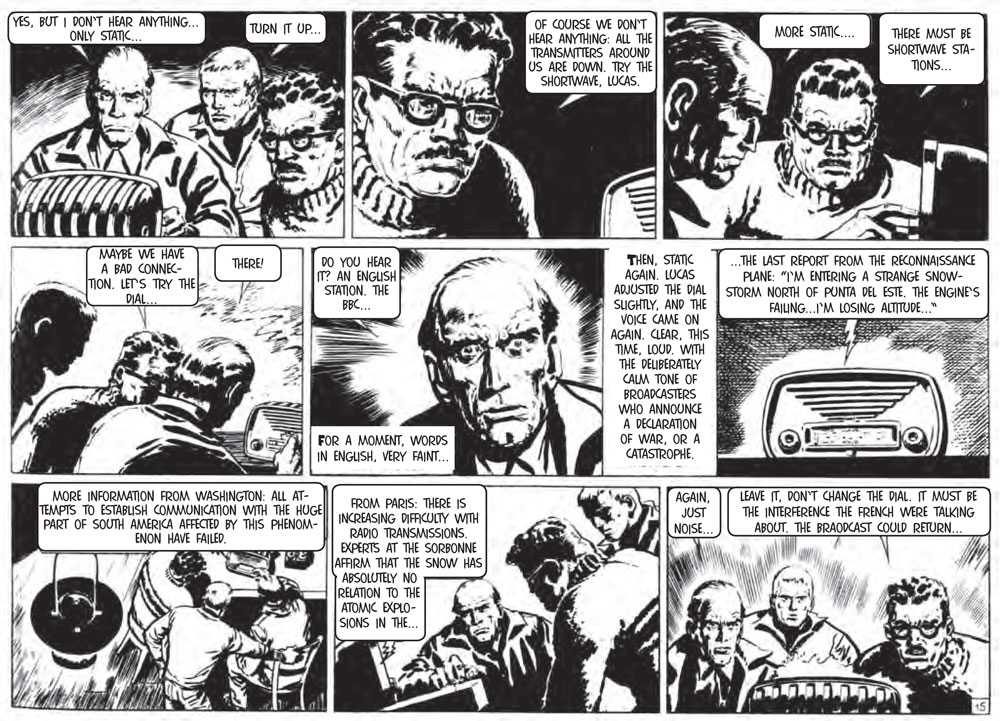

Lucas: YES , BUT I DON'T HEAR ANYTHING ... ONLY STATIC .

Juan: TURN IT UP ..

Favalli: OF COURSE WE DON'T HEAR ANYTHING : ALL THE TRANSMITTERS AROUND US ARE DOWN . TRY THE SHORTWAVE , LUCAS .

Lucas: MORE STATIC ....

Favalli: THERE MUST BE SHORTWAVE STATIONS ...

Favalli: MAYBE WE HAVE A BAD CONNEC TION . LET'S TRY THE DIAL .

Lucas: THERE !

Lucas: DO YOU HEAR IT ? AN ENGLISH STATION . THE BBC ...

FOR A MOMENT , WORDS IN ENGLISH , VERY FAINT ...

THEN , STATIC AGAIN . LUCAS ADJUSTED THE DIAL SLIGHTLY , AND THE VOICE CAME ON AGAIN , CLEAR , THIS TIME , LOUD . WITH THE DELIBERATELY CALM TONE OF BROADCASTERS WHO ANNOUNCE A DECLARATION OF WAR , OR A CATASTROPHE .

Radio Broadcast: ... THE LAST REPORT FROM THE RECONNAISSANCE PLANE : " I'M ENTERING A STRANGE SNOW STORM NORTH OF PUNTA DEL ESTE . THE ENGINE'S FAILING ... I'M LOSING ALTITUDE ... "

Radio Broadcast: MORE INFORMATION FROM WASHINGTON : ALL AT TEMPTS TO ESTABLISH COMMUNICATION WITH THE HUGE PART OF SOUTH AMERICA AFFECTED BY THIS PHENOMENON HAVE FAILED .

Radio Broadcast: FROM PARIS : THERE IS INCREASING DIFFICULTY WITH RADIO TRANSMISSIONS . EXPERTS AT THE SORBONNE AFFIRM THAT THE SNOW HAS ABSOLUTELY NO RELATION TO THE ATOMIC EXPLOSIONS IN THE ..

Lucas: AGAIN , JUST NOISE ,

Favalli: LEAVE IT , DON'T CHANGE THE DIAL . IT MUST BE THE INTERFERENCE THE FRENCH WERE TALKING ABOUT . THE BROADCAST COULD RETURN .

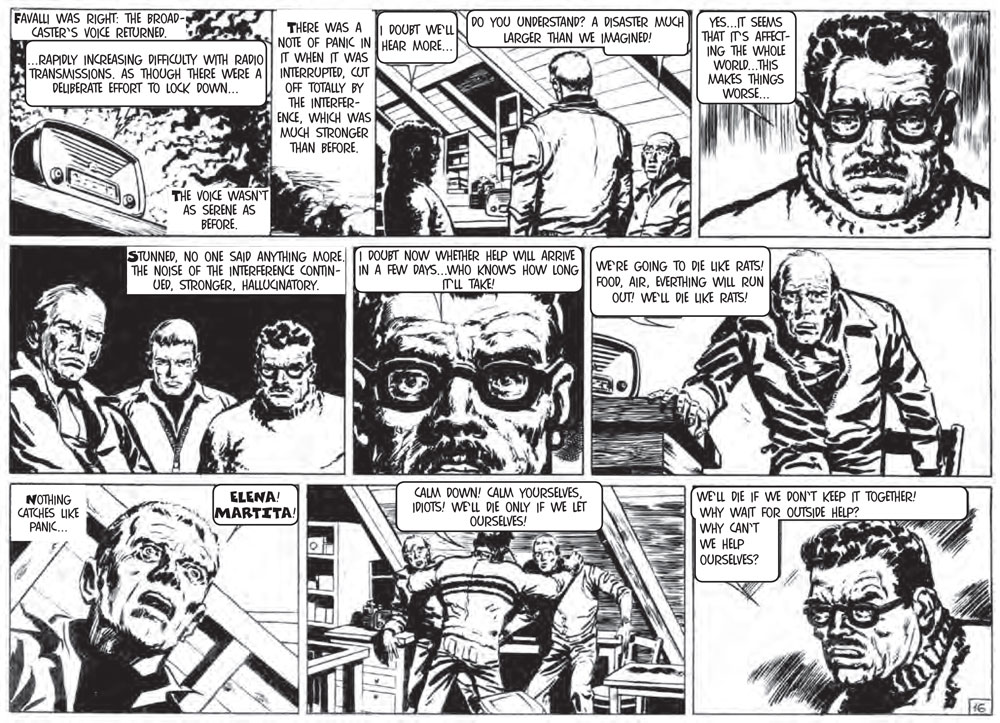

FAVALLI WAS RIGHT : THE BROAD CASTER'S VOICE RETURNED .

Radio Broadcast: RAPIDLY INCREASING DIFFICULTY WITH RADIO TRANSMISSIONS . AS THOUGH THERE WERE A DELIBERATE EFFORT TO LOCK DOWN ...

THE VOICE WASN'T AS SERENE AS BEFORE .

THERE WAS A NOTE OF PANIC IN IT WHEN IT WAS INTERRUPTED , CUT OFF TOTALLY BY THE INTERFERENCE , WHICH WAS MUCH STRONGER THAN BEFORE .

Favalli: DOUBT WE'LL HEAR MORE ..

Lucas: DO YOU UNDERSTAND ? A DISASTER MUCH LARGER THAN WE IMAGINED !

Favalli: YES ... IT SEEMS THAT IT'S AFFECT ING THE WHOLE WORLD ... THIS MAKES THINGS WORSE...

STUNNED , NO ONE SAID ANYTHING MORE . THE NOISE OF THE INTERFERENCE CONTINUED , STRONGER , HALLUCINATORY .

Favalli: I DOUBT NOW WHETHER HELP WILL ARRIVE IN A FEW DAYS ... WHO KNOWS HOW LONG IT'LL TAKE !

Lucas: WE'RE GOING TO DIE LIKE RATS ! FOOD , AIR , EVERYTHING WILL RUN OUT ! WE'LL DIE LIKE RATS !

NOTHING CATCHES LIKE PANIC ...

Juan: ELENA ! MARTITA !

Favalli: CALM DOWN ! CALM YOURSELVES , IDIOTS ! WE'LL DIE ONLY IF WE LET OURSELVES !

Favalli: WE'LL DIE IF WE DON'T KEEP IT TOGETHER ! WHY WAIT FOR OUTSIDE HELP ? WHY CAN'T WE HELP OURSELVES ?

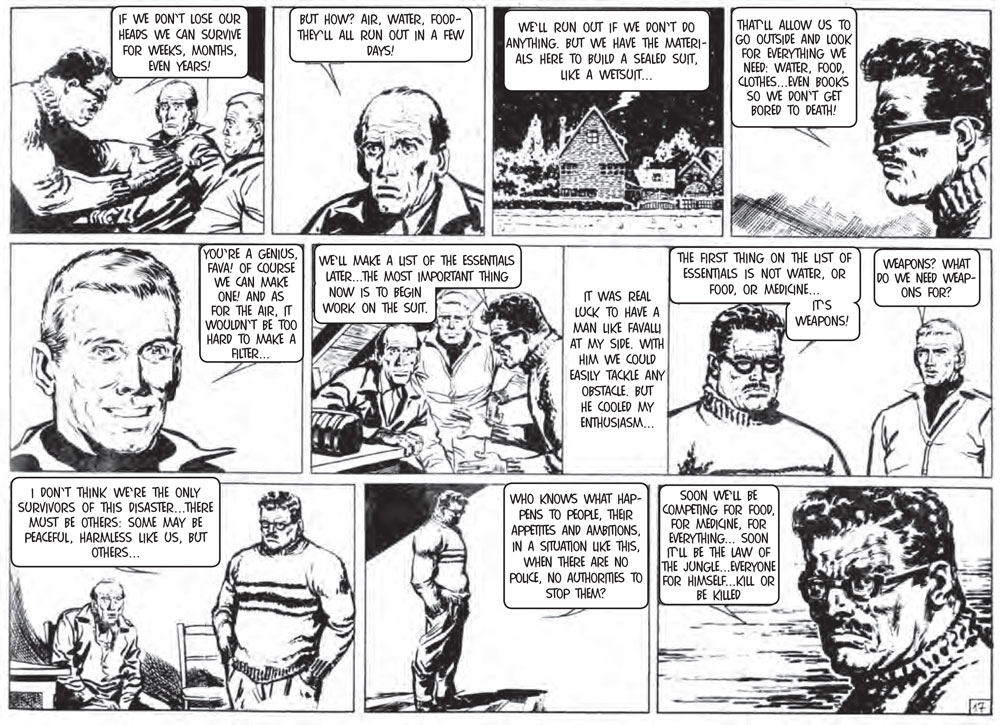

Favalli: IF WE DON'T LOSE OUR HEADS WE CAN SURVIVE FOR WEEKS , MONTHS , EVEN YEARS !

Lucas:

BUT HOW ? AIR , WATER , FOOD THEY'LL ALL RUN OUT IN A FEW DAYS !

Favalli: WE'LL RUN OUT IF WE DON'T DO ANYTHING . BUT WE HAVE THE MATERIALS HERE TO BUILD A SEALED SUIT , LIKE A WETSUIT ...

Favalli: THAT'LL ALLOW US TO GO OUTSIDE AND LOOK FOR EVERYTHING WE NEED : WATER , FOOD , CLOTHES ... EVEN BOOKS SO WE DON'T GET BORED TO DEATH !

Juan: YOU'RE A GENIUS , FAVA ! OF COURSE WE CAN MAKE ONE ! AND AS FOR THE AIR , IT WOULDN'T BE TOO HARD TO MAKE A FILTER .

Favalli: WE'LL MAKE A LIST OF THE ESSENTIALS LATER ... THE MOST IMPORTANT THING NOW IS TO BEGIN WORK ON THE SUIT .

IT WAS REAL LUCK TO HAVE A MAN LIKE FAVALLI AT MY SIDE . WITH HIM WE COULD EASILY TACKLE ANY OBSTACLE . BUT HE COOLED MY ENTHUSIASM ...

Favalli: WITH THE FIRST THING ON THE LIST OF ESSENTIALS IS NOT WATER , OR FOOD , OR MEDICINE ... IT'S WEAPONS !

Juan: WEAPONS ? WHAT DO WE NEED WEAPONS FOR ?

Favalli: I DON'T THINK WE'RE THE ONLY SURVIVORS OF THIS DISASTER ... THERE MUST BE OTHERS : SOME MAY BE PEACEFUL , HARMLESS LIKE US , BUT OTHERS ...

Favalli: WHO KNOWS WHAT HAPPENS TO PEOPLE , THEIR APPETITES AND AMBITIONS , IN A SITUATION LIKE THIS , WHEN THERE ARE NO POLICE , NO AUTHORITIES TO STOP THEM ?

Favalli: SOON WE'LL BE COMPETING FOR FOOD , FOR MEDICINE , FOR EVERYTHING ... SOON IT'LL BE THE LAW OF THE JUNGLE ... EVERYONE FOR HIMSELF ... KILL OR BE KILLED