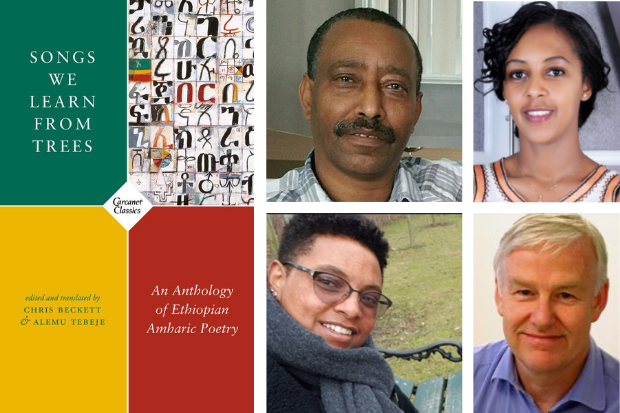

Clockwise from top left: Alemu Tebeje, Linda Yohannes, Chris Beckett, and Mihret Kebede.

Published by Carcanet Press in the UK last year, Songs We Learn from Trees is the first book of Amharic poetry in English translation. Editors Chris Beckett and Alemu Tebeje, themselves poets and translators, present over 250 pages of poetry ranging from folk and religious verse to work by contemporary and diaspora poets. While the anthology provides a representative survey of poems in Amharic, it is still only the tip of the iceberg, opening the door for readers to imagine how much more Ethiopian poetry remains to be discovered and shared with a global community through translation.

I sat down (virtually) with the editors and Mihret Kebede, one of twenty-eight contemporary poets featured in Songs We Learn from Trees, to talk about the anthology, the challenges of translating Amharic poetry into English, and Ethiopia’s vibrant literary scene.

Linda Yohannes (LY): Let’s begin by talking about how the anthology came about. What were you aiming to achieve with this book? And what does the title mean?

Chris Beckett (CB): I wanted to emulate Ethiopian poetry, to get away from writing English-type poems about my childhood in Ethiopia, so I went online and found a website called Debteraw, run by Alemu and dedicated to Tsegaye Gebremedhin. It turned out to be a different Tsegaye Gebremedhin than the one I was looking for—Ethiopia’s poet laureate—but I got to know Alemu as a result!

Alemu Tebeje (AT): After that we started translating poems together. The first poet whose work we translated was Bewketu Seyoum, whom Chris had met in Addis Ababa. We translated one of his poems, “Kezaf yetekeseme zema,” as “Songs we learn from trees,” and we then started sending out our translations to different magazines, like Modern Poetry in Translation, and they were accepted.

CB: There were hardly any Ethiopian poems in English translation before this. I bought The Penguin Book of Modern African Poetry, and there wasn’t a single Ethiopian poet in it. I thought, “We’ve got to do something about this!”

LY: Tell us about your experience translating Amharic poetry (and poetry in general). Mihret’s poem “The Planner” (“Akaj” in Amharic), translated by Uljana Wolf, for instance, is universal: I think an English reader could read the translation and get almost the full experience that an Amharic reader would have with the original. Other poems, meanwhile, are laden with experiences unique to Ethiopians and thus hard to get across in translation.

AT: Yes, it was challenging, to be honest, to translate the substance of some of these poems, especially the ones dealing with historical and social events. It’s hard work.

CB: A poem is not just the meaning. Some poems shout or cry, and it’s very difficult to convey the poet’s voice. I would have liked to have the Amharic original included in the anthology, or an accompanying CD. Quite a lot of the poems in the book were originally written in English, including Hama Tuma’s amazing poem “Just a Nobody.” But when you are translating, I think the most difficult thing is to capture the voice of the poet. Maybe we achieved that in a few cases, but I’m sure we haven’t in others. English just doesn’t sound like Amharic! We don’t have plosive consonants like k’ and p’. Amharic also has the flexibility that inflected language gives you in rhyming and structuring the poem.

Excerpt from “Truth, my child” by Bedilu Wakjira, translated by Hiwot Tadesse and Chris Beckett. Featured in Songs We Learn From Trees, published by Carcanet Press. Poem reproduced by arrangement with the publisher.

LY: I think you’re saying that even when something seems to be successfully reproduced in another language, there’s still a loss.

AT: I can give you an example of this. I wrote a poem, “Basha Ashebir be London” (“Basha Ashebir in London”), inspired by Mengistu Lemma’s “Basha Ashebir be America” [a poem in which an Ethiopian traveler to the United States experiences discrimination and culture shock]. In my poem, I bring Basha Ashebir to Oxford Street, where a dog owner asks him to pet his big dog, but since Basha doesn’t like dogs, he hits it, and then a policeman comes and imprisons him. The dog here is symbolic. I talked to Chris about translating the poem, but in this dog-loving society, we thought it might not be well-received. So we didn’t do it.

CB: Ah, I remember. Maybe I was wrong—should we give it another try?

LY: Since you mentioned Lemma, one of Ethiopia’s most beloved twentieth-century poets, let’s talk about how the older forms of Amharic poetry are viewed by the young generation of poets. Alemayehu Moges, for one, said there are at least sixteen types of Amharic poems: Sengo Megen, Fukera, Mushamushe, Sibikil, and so on. You say in the book that Yewel Bet, lines with two sections of six syllables each, is the most basic and common type. To what extent are contemporary writers studying and writing in these older forms?

Mihret Kebede (MK): When I started writing poems, I studied the structures of Amharic poetry. I had a notebook where I wrote different styles of poems and copied verses by my favorite poets, Gebre Kristos Desta and Mesfin Habtemariam, both of whom are also painters. I used to collect these older poems and artworks, because I’m a painter and visual artist by training. But after some time, I found myself thinking differently. I also saw that my peers were writing in their own way (even though there are some enduring forms like Tsegaye Bet), and I enjoyed that. I know these older forms are taught at schools and in the literature department at the university, but I don’t see many writers using them or even talking about them.

“There were always spies coming to attend our events.”

AT: I think poetry has gone through a lot of turbulence in Ethiopia, and its role has changed in different political eras. We can say that, during the time of Mengistu [the president of Ethiopia from 1977 to 1991], poetry was dead. There were no opportunities for young writers to publicly share their work. But since Mihret and friends started the Tobiya event [a popular monthly poetry and jazz show in Addis Ababa], I see that a lot of new poets are coming up, and it’s really great. I haven’t studied the writing styles the young are using, but there must be some influence from earlier generations.

CB: I think just by reading older poets, you’ll be influenced in some way. In the UK we have Shakespeare, whose work we all have inside us, even if we don’t talk or think about it. In Ethiopia, you also have the Azmari minstrels, who belong to a poetic oral tradition that is still very present, unlike in Europe or America.

LY: What you said about the Derg’s military regime [officially “the Provisional Military Government of Socialist Ethiopia,” which ruled Ethiopia from 1974–91] is interesting, Alemu, because some authors have claimed that the Derg was a period in which we experienced “the closure of the Ethiopian mind.” What do you think happened during those decades?

AT: During the time of Colonel Mengistu, everything was censored. Two friends and I (one went on to write the Ethiopian national anthem; another is a great playwright and poet in exile) once got together and compiled our poems and submitted them to Kuraz, which was one of the two publishers in Ethiopia during Mengistu’s time. We got rejected. Kuraz was owned by the Ethiopian Workers’ Party, and everything had to be submitted to the government censorship department. Even plays and actors were censored. I remember a play in which one of the actors looked too much like Mengistu, and the managers were asked to replace him. It was too close for comfort, I guess! Everything had to praise the revolution and the party. But earlier, during the time of King Haile Selassie I [the Ethiopian king who ruled from 1930–74], protest poems really flourished and poetry played an important role in various social movements. And those good old days seem to be coming back thanks to events like Tobiya Poetry and Jazz.

LY: Tobiya Poetry and Jazz is very big right now—each month close to two thousand people attend. I’ve never been, but people seem to love it, especially Frash Adash [a satirical monologue on social and political issues], which my husband always makes sure he doesn’t miss when it’s released on YouTube (and always makes sure that I sit down and watch with him)! You can feel the energy in the room—it’s a space where people come together to share and reflect on the issues that affect their public and private lives. It seems we’re seeing a poetry revival, partly inspired by Tobiya, but maybe also due to the opening up of political and intellectual space in Ethiopia today.

MK: When I moved to Addis Ababa from Dessie, where I’m from originally, the first thing I did was try to find poets. I soon found out about the Pushkin Cultural Center, where there was a monthly poetry reading organized by the playwright and poet Gashie Ayalnew Mulatu. After the first time, I never stopped going, and that’s where I met all of my contemporary friends and poets. Musicians from the Yared Music School formed a band called Hara Sound, and at their very first performance at the Alliance Ethio-Française in 2008, they invited me to read a poem. I proposed that we invite many other poets and prepare music for each poem. They got excited about that, and we started to rehearse with all the poets: Demissew Mersha, Misrak Terefe, Frezer Admasu, Abebaw Melaku, and Dr. Fekade Azeze. It was a very new approach, and the reception from the audience was amazing, so from then on, we started doing more poetry and jazz events. In 2011, we started Tobiya Poetry and Jazz at Ras Hotel, and it’s still running. It has inspired a lot of similar events within Addis Ababa and other parts of the country. Recently, we published our international poetry and jazz collaboration with the Institute for Spatial Experiments/Studio Olafur Eliasson titled Wax and Gold: Poetry and Jazz (featuring writing in Amharic, English, and German).

Tobiya Poetry and Jazz monthly event in Addis Ababa

AT: Technology also creates a lot of opportunity. As you say, Linda, the political space is more open now, even though many barriers remain, including indirect censorship of publications and poets. The road is not entirely cleared of obstacles, political or otherwise, but poetry is coming back to our society.

MK: Yes, it’s not like we haven’t faced challenges. We resisted attempts to silence Tobiya during the previous government. There were always spies coming to attend our events. One time I received a call from the government office telling us to stop the event. They said, “We’ve been following you for six months, and you are always going against the government. Either stop it or we will.” We had to negotiate with them. One time, they came through the backstage without notice and recorded our show, using their own camera crew. Our jazz musicians and poets managed to improvise on stage, but the audience was a little bit confused and came to ask us what was wrong because all the poems were about love or the landscape [as opposed to critical sociopolitical topics].

CB: Despite the poetry revival you mentioned, Linda, the thing that really stuck out for me as we were putting together the anthology was how few women poets we came across. We knew Mekdes Jemberu and Meron Getnet, and thankfully Lemn Sisay told me about Tobiya, so the next time I was in Addis, I met Mihret and Misrak Terefe. Women prose writers of the Ethiopian diaspora, like Maaza Mengiste and Aida Edemariam, have exploded, but I think poets are just as worthy of note. One example is Kebedech Tekleab, the fantastic painter-poet who lives in New York. Of course, poetry is still not the road to riches, whether local or global!

We should also emphasize that Ethiopia is not just Amharic! Since Alemu and I know very little about Oromo, Tigrinya, or any other Ethiopian literatures, I feel our anthology is only the tip of the iceberg. That makes me proud but humble, too. I hope there’ll be many more anthologies . . . for example, I’d love to be involved in an anthology of Ethiopian women poets.

| LY: On the topic of languages, we seem to agree that there is a need for a more decentralized poetry scene in Ethiopia. As you were saying earlier, Chris, poets are not really driven by financial aspirations, so their work can thrive away from centers of power and money. What do you think is the way forward for poetry in Ethiopian languages other than Amharic? |

MK: Though a poet recently presented in Afan-Oromo at Tobiya, and the amazing poet Yohannes Molla writes in Guraginya as well as Amharic, it’s rare to see writers working in the other languages of Ethiopia. This is of course for historical reasons. We need to create platforms where people are heard in different languages, but unfortunately our languages have become politicized and are used as a tool to divide us.

“The politics of ethnicity is toxic everywhere.”

AT: We have to think about the fact that for historical reasons, Amharic is the lingua franca of Ethiopia. It has been the official language since the seat of the Ethiopian state moved to Lalibela. Today, if you combine native speakers and second-language speakers, Amharic is probably the most widely spoken language in the country. So when a writer publishes or presents their work, they often think about the reach of their medium. If you want a large audience, Amharic will inevitably be your first choice. But that doesn’t mean writers should be discouraged from expressing themselves in their chosen language or mother tongue. I think the way forward is to respect individual choice and encourage writers of different languages. At the same time, if we’re going to live under the umbrella of Ethiopia, one country, it’s useful to have a common language that most of us speak.

LY: I don’t think we can talk about Ethiopia today without mentioning what we’re seeing in the news. There’s the war in Tigray, and we’re also hearing reports of violence across the country. Our politics seem to be about our differences rather than what we might have in common. As poets, what do you think about the current political situation, and how do you think poetry comes into it?

CB: The news is so distressing. The politics of ethnicity is toxic everywhere. And the funny thing is that just a few years ago I was noticing how many poems there were about how, despite ethnic differences, we have to remember we are all Ethiopians. Yet here we are. It’s something poets have been sensitive to for many years, I think, this brewing ethnic tension. And that’s the subject of poetry. Poetry has to deal with difficult topics, and Ethiopian poets are dealing with this one.

MK: Since 2015, I’ve been working on a collection of what I call #evolutionarypoems, which trace the social and political dynamics in the country. I’ve now written 166 evolutionary poems, and I’m just one person. If you follow others’ work, you can see chronologically what has been happening and notice that things are repeating themselves. Sometimes I don’t have to write another poem: the poem I wrote back in 2017 could be used instead. We are in a vicious circle, unfortunately.

I also don’t think these problems originate from within the country alone; there is a link to global capital and power relations. We need to be conscious of that to solve this situation.

LY: Before we wrap up, what are you reading these days?

AT: I recommend Hama Tuma and Gemoraw. The latter is mainly known for Berekete Mergem, but he wrote and published work in English, Amharic, Swedish, and Chinese. Much of his unpublished work is held by Sweden’s central library.

MK: I recommend watching the monthly Tobiya Poetry and Jazz event, which has now moved to the Ethiopian Airlines Skylight Hotel, on the YouTube channel of our media partner Arts TV World. Readers may also be interested in the poetic Saturdays event at Fendika Cultural Center, a vibrant hub for Ethiopian folk and jazz music. A book I enjoyed recently and would recommend is Silence Is Not Golden: A Critical Anthology of Ethiopian Literature by Taddesse Adera and Ali Jimale Ahmed.

CB: I recommend visiting Carcanet’s Youtube channel for great readings by poets from the anthology, including Lemn Sissay, Misrak Terefe, Alemtsehay Wodajo, Zewdu Milikit, Makonnen Wodajeneh, and Alemu, too.

Chris Beckett was born in London but grew up in Ethiopia. His second collection of poems, Ethiopia Boy, was published by Carcanet/Oxford Poets in 2013. Sketches from the Poem Road, a collaboration with Japanese artist Isao Miura, was shortlisted for the Ted Hughes Award 2015. His translations (with Alemu Tebeje and others) have been published in Modern Poetry in Translation, PN Review, The Missing Slate, and Asymptote Journal. With Gale Burns, he co-hosts The Shuffle reading series in Covent Garden. He is a trustee of the Anglo-Ethiopian Society and the Poetry Society.

Mihret Kebede is a multidisciplinary artist/poet who graduated from Addis Ababa University School of Fine Arts and Design in painting with distinction in 2007 and earned her MA in arts from the same school in 2016. She has participated in several local and international art exhibitions, workshops, poetry performances, art residencies, and collaborative art projects. Beyond her artistic practices, she is also known for organizing local and international art events and festivals. She is a co-organizer and founding member of Addis video art festival and popular monthly poetry and jazz event Tobiya Poetic Jazz and a founding director of Netsa Art Village, an artists’ collective that was closed by government officials in 2015 after seven years of serving Ethiopia’s contemporary art scene. Her poems and essays are included in Wax and Gold: Poetry and Jazz, published by Institut für Raumexperimente/Studio Olafur Eliasson and Tobiya Poetic Jazz; and in the first-ever anthology of Ethiopian Amharic poetry in English, Songs We Learn from Trees, published by Carcanet Press. She is currently a PhD candidate at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna with a working title Conversing with Silence.

Alemu Tebeje is an Ethiopian journalist, poet, lyric writer, and human rights campaigner who left Ethiopia in the early 1990s and now lives in London, close to Grenfell Tower. He studied Ethiopian languages and literature, and journalism, at the universities of Addis Ababa and Wales, respectively. He runs the website www.debteraw.com. His poems have been published in Amharic, Chinese, and English, and have been projected on buildings in Denmark, Italy, the US, and the UK by the artist Jenny Holzer. He has published one collection of poems, Greetings to the People of Europe! (Tamrat Books, 2018), which includes the script of a sketch commissioned by BBC Radio 4 for its migrant reimagining of Homer’s Odyssey, “My Name is Nobody.” With Chris Beckett, he cotranslated and coedited the very first anthology of Ethiopian poetry in English, Songs We Learn from Trees, and set up a small publishing company called Tamrat Books to bring the beauty of Ethiopian poetry and letters to an English-language readership.

Related Reading:

“The World Between: Writing from Ethiopia and Italy” by Maaza Mengiste

“Please Come for Me!” by Misrak Terefe, translated by Chris Beckett and Yemisrach Tassew

“The True Story of ‘Faccetta Nera'” by Igiaba Scego, translated by Antony Shugaar