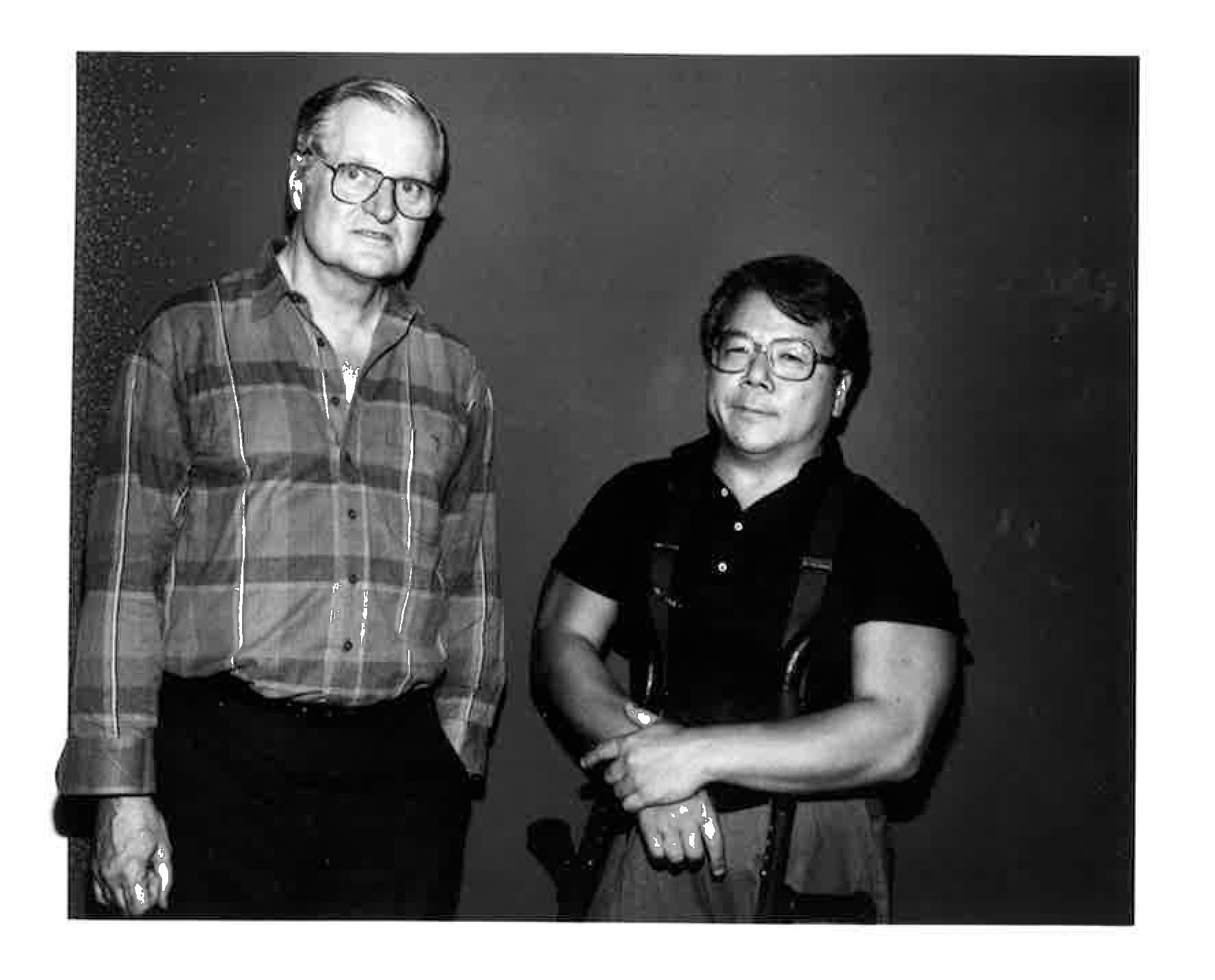

Photo Credit: Seiji Kakizaki. John Ashbery and Hiroaki Sato in September 1991, on the occasion of the publication of Sato’s translation of A Wave into Japanese.

Toward the end of 1973, I was about to move from my apartment on the Upper East Side to one in Chelsea when I received a card. To my surprise, it was from John Ashbery, saying he liked my translation just out, Spring & Asura: Poems of Kenji Miyazawa. Not that I’d known him in person. It was my fifth year in New York, where I’d moved as soon as I finished my graduate studies in English and American literature, in Kyoto, and I recognized the name Ashbery only because it was in one of the books I bought here, such as Donald Allen’s The New American Poetry, as I started translating Japanese poetry, though it’s possible that Michael O’Brien, the poet who had helped me translate Miyazawa, told me about him.

During the 1960s, Japanese college courses in English poetry stayed with safe greats: Sidney, Shakespeare, Herrick, Dryden, Keats, Shelley, Tennyson, Browning, Dickinson, Whitman. I’d read Pound because my poetry teacher, Lindley Williams Hubbell, taught “Hugh Selwyn Mauberley” with notes that he mimeographed for us. Thanks to Hubbell, too, I’d read some Eliot, including “The Waste Land.” But even Hubbell, the 1927 recipient of the Yale Younger Poets prize for his Dark Pavilion, did not cover Beat poets, despite the fact that Ginsberg and others were all the rage in Japan around 1960, something I learned belatedly—only a few months ago, in fact—in writing about Kazuko Shiraishi’s book of poems in Yumiko Tsumura’s translation, Sea, Land, Shadow.

Ashbery had included his address, and it was, to my further surprise, on the street I was moving to. I wrote him at once to thank him. Was I also forward enough to tell him I’d be his neighbor soon and propose to meet him? Perhaps. Along with Spring & Asura, I had three other translations out that year: Poems of Princess Shikishi (a chapbook), Ten Japanese Poets, and a special issue of the Chicago Review, Anthology of Modern Japanese Poets. So, not long after settling down in the new apartment, I walked west, past just a half-dozen buildings, to see him.

That evening, when asked what I would like to drink, I said vodka—my drink since a few years earlier, when the two women who asked me to “teach” them haiku, Eleanor Wolff and Carmel Wilson, invited me to a restaurant called Napoleon. My college days in Japan just over, I wasn’t used to American restaurants with a battalion of liquor bottles or, for that matter, American etiquette. Thus, when Miss Wolff asked me, “What would you like to drink?” I was at a loss. Quickly discerning my plight, she, who had spent her youth in Paris, summoned a garçon—and the garçon recited a long list of liquors. Confused, I meekly said, “The first one.” That was vodka. Thus it had become my drink during the soirées before each haiku session at either of the two ladies’ places.

Ashbery fetched me a drink. He didn’t drink himself, saying he was on the wagon. I got drunk fast. And what did I prattle on about? The art of translation! I was full of myself, to be sure.

In the following days, and years, when I stepped out the front door of my building to go to work, I’d occasionally see him, and when he happened to see me, he’d smile. Most often, I’d see him walking away. In those days, in New York City, dogs could drop their feces anywhere on the street and their owners weren’t required to collect them. Was he negotiating those hazards as he walked? I had read a story about Wallace Stevens: a woman who lived in a house on a street Stevens took every morning to his insurance company would sometimes see him stop and walk backward a couple of steps, as if rearranging the rhythm of the verse he was composing in his head.

I learned—probably from Robert Fagan, the poet who was helping me translate at the time and for a long time afterward—that Ashbery was the poetry editor of Partisan Review, and I sent him Ozaki Hōsai’s haiku, a batch of 150, all translated in one line. Hōsai (1885–1926) was among the haiku writers who started ignoring the two basic requirements of the genre: the form of five-seven-five syllables—defining the haiku as a verse form of three lines is a foreign invention—and the inclusion of a seasonal indicator, kigo. To my surprise again, Ashbery accepted the whole set, without comment, and published it in the January 1979 issue of his magazine. For a magazine to accept so many haiku at once may have been unheard of, before or ever since, in Japan, let alone the United States.

In the summer of 1982, Hisao Kanaseki, a scholar of modern American literature whom I knew arrived in New York, under the aegis of the U.S. Information Agency, to visit a dozen artists, Ashbery among them. Since Ashbery lived on the same block, Kanaseki came to visit me after interviewing him and said Ashbery told him that he learned about the genre haibun—a short essay-like prose piece written with a haikai spirit, usually accompanied by a haiku or two—from the anthology of Japanese poetry that I translated with Burton Watson, which had come out in the previous year under the title From the Country of Eight Islands. I was happy, then, to see Ashbery’s book of 1984, A Wave, include “37 haiku,” composed all in one line, and six haibun. A few years later, when a chance arose for me to write a book about English haiku, in Japanese, I included four of Ashbery’s haibun.

When that book, Eigo Haiku, with the English title, Haiku in English: A Poetic Form Expands, came out in 1987, the Japan Society had an event for it, and its auditorium was packed—clearly because of the popularity of haiku, but also because of Ashbery’s participation. And because of him, a New Yorker writer came and during the reception talked to me, with a small tape-recorder in one hand. But I evidently failed to say anything that would have tickled the suave readers of the weekly. Whatever she might have written didn’t make it to “The Talk of the Town.”

One day in 1989, Ashbery telephoned me to say he was in trouble: a Japanese professor who had invited him to Japan for a round of readings told him he couldn’t come with his partner, though Ashbery told the professor he’d happily pay for his expenses. So I called Kanaseki, and Kanaseki called the professor, and the matter was settled. Kanaseki had much greater academic weight in Japan. In a recent letter, Ashbery’s partner, David Kermani, told me that the professor was “not a nice person” in Japan, either, so the two visitors took to calling him “Mr. T”—a popular figure in the U.S. entertainment business at that time.

So it was Ashbery, and his book A Wave, that I chose when the Tokyo poetry publisher Shoshi Yamada agreed to do a book by an American poet in my translation. My translation, as you can imagine, endlessly flummoxed the publisher’s editors, however much they were used to some of the more intractable modern Japanese poetry. Ashbery’s poetry, in stark contrast to his art reviews in New York and other magazines, was infamously “opaque,” or, as Larissa MacFarquhar put it in the New Yorker, of the kind that made readers wonder “why he had to go so far out of his way to contort his sentences, if ‘sentences’ was even the right word for whatever they were.”

There also was my cultural and literary deficiency. For example, I didn’t know that Sabrina in “Description of a Masque” originally came from Milton’s masque Comus (though I had majored in English literature) until my poet friend Geoffrey O’Brien pointed it out to me. I had thought the name referred to the heroine of Billy Wilder’s film of that title starring Audrey Hepburn. So I provided my translation of Ashbery’s “Masque” with half a dozen footnotes, though that was an exception.

Ashbery, who had lived in France for about ten years, said that when his poems were translated into French, he helped his translator. But I did not bother him with my translation. It wasn’t just that he evidently didn’t know Japanese, but I knew that once I started asking him questions, I would have drowned him.

I must add that I was particularly presumptuous in translating A Wave. At the time, I read somewhere an article about him—perhaps in the New York Times Magazine—that Ashbery worked for a set amount of time every morning, without fail. I decided to copycat him and tried to work on translating A Wave for a certain amount of time every day, regardless.

Nami Hitotsu came out in 1991. It looked more impressive, I dare say, than the original, from Viking. With 300 pages, it was three times heftier than the ninety-page original. Shoshi Yamada is famous for turning out beautiful books, and my translation was stylishly produced, with the cover design incorporating the sculptor Masaaki Noda’s painting “Inducement.” The book came with a pamphlet, a selection of writings on Ashbery—an essay Geoffrey O’Brien wrote for the book, as well as excerpts from commentaries by Harold Bloom, Helen Vendler, Alfred Corn, Richard Howard, Charles Berger, and Anita Sokolsky. In my translator’s afterword, I contrasted Ashbery with Gary Snyder, who had written a blurb for Spring & Asura. To do so, I quoted the two poets’ autobiographical statements included in Paris Leary and Robert Kelly’s anthology, A Controversy of Poets, and ended with my translation of Snyder’s poem “Civilization.” In essence, I wanted to have Ashbery represent “culture,” Snyder “nature.”

When I received copies from Tokyo, I took a couple to Ashbery. During some chitchat, he asked how it came about that I translated a book of his. I told him that back in 1973 he had sent me a card complimenting Spring & Asura. He said he didn’t remember doing that at all.

A few weeks later, we had a party with him and several other poet friends of mine reading in Lenore Parker and Robert Fagan’s loft. My photographer friend Seiji Kakizaki, who had taken some memorable shots at the party for my first books eighteen years earlier, was on hand to take some good photos.

Nami Hitotsu was praised by a number of Japanese poets. Among them was Kazuko Shiraishi, who wrote a long review, concluding that through my translation she could see “one gleaming wave” in the offing of “mystery and maze.” But Nami Hitotsu didn’t sell—in fact, the publisher, Shoshi Yamada, lamented a few years later that of all the books it had published, Nami Hitotsu was the worst seller. It is still available from the publisher, if not from Amazon or any other bookseller.

I might have expected something like that. I hadn’t asked for a translation fee. And, knowing that it would cost a bundle if the publishers got involved, I talked to Ashbery. He agreed to skip his publisher, giving his personal permission for the translation and its publication free of charge.

Following Nami Hitotsu, there appeared two Ashbery books in Japan, as far as I can tell. One is Selected Poems of John Ashbery in the Shichōsha series of modern American poetry in collaborative translation. The series is based on the idea that if a translator and a poet work together, the result will be best—that a poet should be able to transform a mere translation into “poetry.” In the case of the Ashbery volume, which came out in 1993, the poet was Ōoka Makoto, a prolific literary critic who himself did a good deal of translation from French, and the translator the scholar of American literature Iino Tomoyuki.

(As I write this, I remember my vague puzzlement two decades ago. In 2000, when Ōoka spoke at the annual Sōshitsu Sen Lecture Series at Columbia University, Ashbery was in the audience and at the dinner that followed, and I wondered why. Now I know. Ōoka had worked on Ashbery’s poems.)

In 2005, Iino Tomoyuki published a book of essays on Ashbery under a title that may be translated John Ashbery: Poetry “in Praise of Possibilities,” abundantly quoting Ashbery’s original poems, followed by his own translations. The established house Kenkyūsha, famous for its English-Japanese and Japanese-English dictionaries, published the book.

Have these two books affected Japanese readers’ understanding of John Ashbery? That is hard to guess. Some may have found inspiration in the way he wrote; but Japanese poets have been writing in quite unconventional ways for a long, long time.

© Hiroaki Sato. All rights reserved.