44° 40’ 36.4” N 124° 4’ 45.9” W

Yaquina Head Lighthouse. Brick tower painted white, 28 meters high. Original Fresnel lens, visible at 31 kilometers. Blink pattern: two seconds on, two seconds off, two seconds on, fourteen seconds off.

Yaquina Head

We arrive in Portland, Oregon, to stay with Willey, my aunt’s boyfriend. In his youth Willey had been an EMT and a member of the Black Panthers; he had a daily routine that included a plentiful breakfast of ham and eggs, wheat semolina, and toast, reading the newspaper, and smoking two or three cigarettes on the balcony of his home.

I don’t smoke, but during my first day in that house I spent a long time on the balcony watching the river with its boats and seabirds. I guess that’s equivalent to smoking. The following day we took the highway south. My cousin—two meters tall—and I were squashed in the back seat of the red pickup Willey referred to as “my baby.” We spent a night at the snow-capped hotel where The Shining was filmed, en route to the crater of an extinct volcano that is now a sapphire-blue lake.

Two years later, when I returned to Portland with my mother and aunt, Willey drove us to the coastal city of Newport. It was September. In that same pickup, we traveled along a wooded highway, stopping at a diner halfway to our destination to eat cupcakes made from locally grown marionberries, served by a couple of kindly old men. I remember that I had my headphones on, and was looking out the window at the forests of bare trees with trunks that were first dark, then white, and finally red. In Newport, I felt I’d never before seen an ocean so gray, so cold. Even in summer, the whole city is shrouded in mist, and you have to search for your hotel among the clouds.

***

Even before I ever saw a lighthouse, I dreamed of one; it was abandoned, far from the coast. At the foot of the building was a garden and the house where I lived with my parents. In my childhood dream, I asked my father what he’d found during his exploration of the crumbling rooms. “Just the skeleton of a bat,” he said. I insistently asked for reassurance that the animal was dead, but he only muttered to himself, like someone in the trailer for a horror movie: “Dead, but alive.” The tip of the tower was visible: a dark garret where the bony hands of the bat’s skeleton stirred a cauldron containing a potion. The camera then zoomed in on the skull, which in a squeaky voice said, “I’m brewing my revenge on the person who killed me.”

***

In Moby Dick, Melville says that human beings “share a natural attraction to water.” At one point Ishmael offers an explanation for why people fritter away their savings and bonuses to visit such places as that sapphire-blue lake in the crater of a volcano, or a waterfall so high that the liquid evaporates before reaching the rocks, or a series of pools in the middle of the desert that are home to tiny prehistoric beings, or a natural well deep in the jungle. He explains the amazement we feel at the sight of the color now called International Klein Blue, or the turquoise of the Bacalar lagoon in Quintana Roo. Ishmael suggests that all men’s roads lead to water, and the reason why no one can resist its attraction is also why “Narcissus, who because he could not grasp the tormenting, mild image he saw in the fountain, plunged into it and was drowned. [. . .] It is the image of the ungraspable phantom of life; and this is the key to it all.”

That reflective power of water made Joseph Brodsky believe that if the “Spirit of God” moved upon its surface, the water would surely reproduce it. God, for Brodsky, is time; water is, therefore, the image of time, and a wave crashing on the shoreline at midnight is a piece of time emerging from the water. If this is true, observing the surface of the ocean from an airplane is equivalent to witnessing the restless face of time.

No civilization bordering the sea, with lakes, or with important rivers has been immune to the need to navigate those waters, to explore the furthest reaches of the oceans, to transport or be carried on the waves. And yet mariners appear as vulnerable aboard their ships as penguins do ashore. Although familiar and necessary, water is also unknowable and menacing. Despite the fact that it makes up the greater part of the human body, it can also take human life.

The earliest lighthouses are the product of a collective effort to signal dangerous areas or the proximity of coastlines and ports. Shipwrecks may be less common nowadays, but for a long time they were everyday occurrences: 832 in English waters in the year 1853, according to Jean Delumeau; the author quotes Rabelais’s character Pantagruel confessing to his fear of the sea and his terror of “death by shipwreck.” And citing Homer, Pantagruel adds, “it is a grievous, abhorrent and unnatural thing to perish at sea.”

The Hells of many mythologies can only be reached by boat, they are surrounded by water because, as Delumeau notes, in antiquity the ocean was associated in the collective mind with the most awful images of pain and death, the night, the abyss.

The Maya used to build monuments lit from within to signal places where it was possible or perilous to bring a boat ashore. The Celts used beacons to send messages along the coast. But it was the Greeks who gave these lights the name Pharos.

Fire indicating the sea’s end. In The Iliad, Homer speaks of burning towers with bonfires that had to be constantly fed, like the sacred flames in temples dedicated to Apollo. He compares the lustrous glow rising to the heavens from Achilles’s shield to the “blazing fire from a lonely upland farm seen by sailors whom a storm drives over the plentiful deep far from their friends.”

Apparently during the Trojan Wars there was a lighthouse at the entrance to the Hellespont, and another in the Bosphorus strait. Suetonius says there was once a lighthouse on the island of Capri, and Pliny the Elder mentions others in Ostia and Ravenna (he also warns of the danger of mistaking them for stars). Herodian refers to towers in ports “which by the light of their fires bring to safety ships in distress at night.” These are the precursors of the lighthouse whose name passed into so many Romance languages: faro in Spanish and Italian; phare in French; farol in Portuguese; far in Romanian. Precursors of the “Pharos” of Alexandria. On the island of Pharos, visited by Odysseus, which “has a good harbor from which vessels can get out into open sea,” there was a huge guardian lighthouse that Ptolemy I, the Macedonian general of Alexander the Great, ordered to be constructed in the third century BC.

It was a tower of some 135 meters, constructed from pale stone, with a glass dome crowned with flames and a statue of the god Helios. It’s said that its architect, Sostratus of Cnidus, chiseled his name in the stone, plastered over it, and then inscribed that of Ptolemy on top, knowing that the plaster would eventually crumble so it would be his name that survived. The flame was tended day and night, and ships’ crews could see it fifty-six kilometers offshore. It remained in existence longer than the Hanging Gardens, longer than almost any other of the seven wonders, until, in 1323, an earthquake brought it down. But Alexandria will always be the city of the lighthouse, a huge ghost set down in history.

“The same streets and squares will burn in my imagination as the Pharos burns in history,” says the narrator of Justine, the first book of Lawrence Durrell’s Alexandria Quartet. In this work, the protagonist merges with the city, both of them seductresses, tempestuous and unattainable.

Later, lighthouses began to spring up in other parts of the world. In Rome and the surrounding lands high towers, such as the one dedicated to Hercules in La Coruña, were located at the entrances to ports in imitation of Alexandria. It’s said that, in his madness, the emperor Caligula declared war on Neptune and attempted to insult him by collecting shells on the seashore, but as Neptune made no response, the emperor decided that he’d won. He celebrated this victory “by the erection of a tall tower, not unlike the one at Pharos, in which the fires were kept going all night as a guide to ships.”

Firewood was the first fuel source for lighthouses, followed by coal, and later pitch. Then came oil and gas lanterns, and with the availability of electric power, light bulbs were used in conjunction with the magnifying properties of Fresnel lenses: fantastic vitreous heads like prehistoric monsters that can transmit light for many kilometers.

The oldest lighthouses still in existence date from the Middle Ages. The Germans at times used beacons to warn sailors of the proximity of the coast. In those days the custodians of lighthouses were monks, who took on the task out of the kindness of their hearts. Their voluntary work was in contrast to the attitude of certain monarchs, who awarded themselves the rights to everything that washed up on their shores (men and women included). That is the reason for the prosperity of such lands as Normandy, where the swirling tides often swept ships onto the rocks. During this period giant pagodas that served as lighthouses were also being built in China.

In 1128, the Lanterna was constructed in Genoa; in 1449, one of its lighthouse keepers was Antonio Colombo who, according to several sources, was the uncle of the infamous seafarer Christopher Columbus.

***

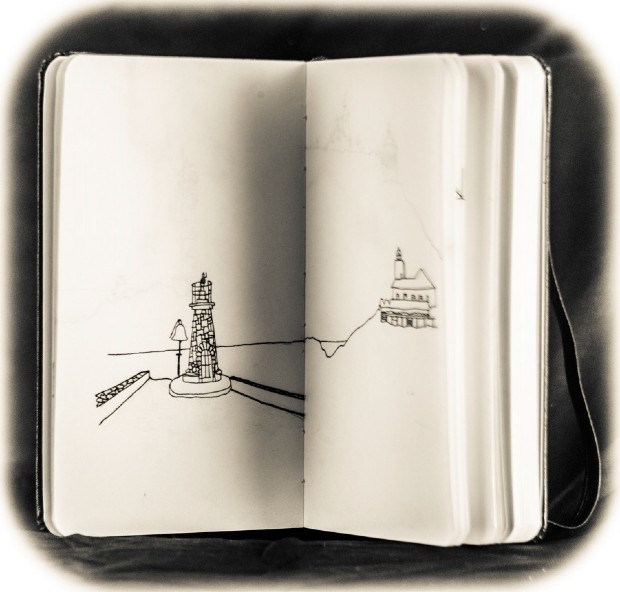

Sylvia Beach Hotel in Newport was opened on a whim by two women with an obsession for literature. It’s an enormous house full of cats and retired ladies who travel in groups and wear hats (close relatives of men who construct ships in bottles, of those who go on bird-watching vacations, and of those—of us—who collect tiny replicas of lighthouses). The hotel has a library in the attic and around forty rooms dedicated to well-known writers: there’s an Emily Dickinson, a Walt Whitman, a Jane Austen, plus a Shakespeare, a Melville, and a Gertrude Stein (although the premises take their name from Joyce’s patron, there is no bedroom dedicated to the author of Ulysses). The decor of the suites reflects the respective periods and tastes of the writers, with their complete works on the bookshelves. I would have loved to sleep in Virginia Woolf, with its Victorian furnishings and a window looking out to sea, giving a distant glimpse of Yaquina Head and, on its promontory, the lighthouse. I’d just started reading To the Lighthouse: it’s not clear to me now if it was a matter of chance or, knowing that I was going to visit such a building, I forced the coincidence.

The lighthouse in Woolf’s novel takes its inspiration from one located on the coast of Cornwall, where the author used to spend the summer with her family: a small white structure with many windows, built on an island. To the Lighthouse opens by a window, with Mrs. Ramsay’s promise to her son James that the following day, if the weather is good, they will visit the lighthouse near their summer home. Later, she repeats this promise while knitting a pair of socks for the tubercular son of the lighthouse keeper. Mrs. Ramsay imagines the keeper there, alone, week after week during the stormy season, the waves breaking against the lighthouse, rocking its foundations, covering it in surf. Directing her words to her daughters, Mrs. Ramsay says one should take lighthouse keepers “whatever comforts one can” because it must be terrible and very boring to be shut up there for months on end with nothing to do.

***

I live on an island, on the fifth floor of a red building. The plaque in the hallway says it’s the fifth, but for reasons no one has been able to explain to me, there are two second floors. I rarely leave this brick tower. When I do, it’s almost always at night, or to visit lighthouses.

There are four windows. Two have bars that were installed a while ago when a burglar managed to get into the neighboring apartment. The other windows look out onto a brick wall a meter away. That wall is so high that, looking up, you can’t see the sky. And neither can you see the ground below: the gap narrows and the bricks are lost in darkness. I’ve never suffered from claustrophobia, but I sometimes feel an uncontainable need to see the horizon. In this city of tall buildings, that horizon is difficult to find; in order to see anything at any distance you have to go up to a roof, to the river, or to one of the streets that cut across the whole island. From time to time I do one of those things. When I was taking art classes, I learned that my mind often follows the lead of my eyes, and if I restrict my gaze for too long, my thoughts become myopic.

Another problem with the apartment is the darkness. In my bedroom and in the living room a gray, muted, cloudy-day light filters through the windows. The only plant I’ve had here died after only a few weeks. I spend the whole day bathed in artificial light, and to see the sun—if the sky outside is clear and there’s no one else home—I have to press myself up against the bars of the other window and search it out above the buildings.

I wonder what will become of me, spending so much time without direct sunlight; I wonder if I’ll turn into one of those blind, transparent fish that live in subterranean rivers and caves.

It feels as if my nerves are a little more sensitive than the norm. I faint at the prick of a needle; almost all strong emotions give me a headache. Perhaps it’s that I’m not thick-skinned, and people seem a permanent source of danger.

Pain has this ability to become stronger when you think about it. If I concentrate hard on a part of my body, it ends up hurting. If I concentrate hard on myself, I hurt. For instance, right now, as I write this. By contrast, when I visit lighthouses, when I read or write about lighthouses, I leave myself behind. Some people like gazing into wells. That gives me vertigo. But with lighthouses, I stop thinking about myself. I move through space to remote places. I also move through time, toward a past that I’m aware I idealize, when solitude was easier. And in moving back in time I distance myself from the tastes of my own age, when lighthouses are linked with unfashionable adjectives like romantic and sublime. It’s difficult to talk about the topics generally associated with lighthouses: solitude, madness. Those of us who try have no option but to accept ourselves as quaint.

If I focus my attention on myself, the pain is magnified. On the other hand, when I think of myself in relation to a lighthouse, I feel brand new and so tiny that I almost vanish. What I feel for lighthouses is the complete opposite of passion, or at least it’s a passion for anesthesia. Analgesic addiction. I’d like to become a lighthouse: cold, unfeeling, solid, indifferent. When I see them, I sometimes have the sense that I really could turn to stone, and enjoy the absolute peace of rock.

I understand the objections to the desire to escape from the world. I know it can be an egoistic, arrogant desire, the attitude of someone looking down from above, from a tower. That’s why I find lighthouses so attractive: they combine that disdain, that misanthropy, with the task of guiding, helping, rescuing others.

***

Robert Louis Stevenson says that to tour lighthouses is “to visit past centuries,” which is exactly what he does in his book Records of a Family of Engineers. With the help of letters and diaries, he unearths the stories of his father, Thomas, his grandfather, Robert, and the latter’s stepfather, Thomas Smith: all engineers and inventors, pioneers in the creation of lighthouses.

The Scottish coast is a place of rough seas, stormy skies, bleak headlands, “savage islands and desolate moors.” The year was 1786, and along the whole coastline, only a single point shone out: the Isle of May, with a tower dating from 1635 on top of which was a grate with a coal fire. In 1791 the beacon was the cause of a conflagration in which the custodian of the lighthouse and five of his children died. The sole survivor was a girl who was found three days later, permanently transformed by the sight of the flames reflected in the sea.

The Isle of May was the only light on that coastline of shipwrecks and pirates: a single, inadequate light. For this reason, that same year the authorities decided to construct four more lighthouses. This task required engineers—not yet known by that name—whose responsibility it was to build the towers, light the fires, and, starting from nothing, create, organize, and recruit the members of a new profession: the lighthouse keeper. Stevenson’s grandfather and Thomas Smith teamed up with the Board of Northern Lights to illuminate certain strategic points on the coast.

The engineer as artist. Stevenson describes his father’s and grandfather’s profession as if he were talking about Romantic poets. The engineer, as a Wordsworth or a Coleridge, makes his plans with an eye to the natural world. His task does not involve language, but nature itself. For this he needs the ingenuity (the word engineer is derived from Medieval Latin ingeniator, meaning someone who creates or uses an engine) and intuition, which Stevenson calls a “sentiment of physical laws and of the scale of nature.” His “feelings” have to capture the smallest detail. To calculate the height of waves, for instance, the engineer had to take into account the slope of the ground, the configuration of the coastline, the depth of the water near the shore, and the species of plants and shellfish on the site. His observations and instinct stood in for the instruments that would come later with the Industrial Revolution. Stevenson recounts that he often watched his grandfather for hours on end, counting the waves, noting when they receded and when they broke. His task was to predict the unpredictable: how the new structure would affect the tides, increase the strength of the waves, hold back rainwater, or attract lightning. And all this done in the open air while sailing angry, inhospitable seas or, back on land, with only a tent to sleep in.

Villagers also constituted a threat. Superstitious, accustomed to war and violence coming from the sea (the Vikings had arrived in ships), they believed a man saved from the waters would be the ruin of his rescuer. On one occasion, Thomas Smith was mistaken for a Pict (the Scottish tribe that spoke Pictish) and if it hadn’t been for Robert Stevenson coming to his aid, he might have been summarily hanged. Years later, Robert himself was suspected of being a spy: when he happened to ask about the state of the lighthouse in one village, they almost put him to death.

In 1814, Sir Walter Scott traveled to Scotland with Robert Louis Stevenson’s grandfather aboard the lightship Pharos, accompanying a team of lighthouse inspectors. During the voyage Scott wrote a diary in which he mentions Bessie Millie, an old woman who lived in Stromness and earned a living selling favorable winds to seamen. No one ventured to set sail without first visiting Bessie Millie, who prayed for the winds to follow the sailors on their voyage. In order to reach her house, which Scott described as “the abode of Eolus himself,” he had to walk along a series of dangerous, steep, rocky paths. Bessie was close to ninety, skinny and wizened as a mummy, and had a kerchief that matched the pallor of her cadaveric body tied around her head. Her blue eyes shone with the gleam of madness. “A nose and chin that almost met together, and a ghastly expression of cunning” gave the impression that she was Hecate, the Greek goddess of the night and ghosts, says Scott.

The family of Stevenson’s grandfather was replete with pious women and moribund children, but neither poverty nor illness quenched his thirst for knowledge. In the winter months, when voyages were impossible, he sought shelter at the University of Edinburgh. He studied math, chemistry, natural history, agriculture, moral philosophy, and logic within the stone walls that housed Charles Darwin and David Hume during those same years.

He was the first person to construct a lighthouse on a marine rock, far from the coast. Bell Rock had been the cause of many shipwrecks, and it was said to be haunted by the ghost of a pirate. Years later, Robert Louis Stevenson’s father also contributed to the development of lighthouses when he transformed the Fresnel lens by combining it with metal to increase its strength.

“Perhaps it is by inheritance of blood,” says Robert Louis about Cape Wrath, “but I know few things more inspiriting than this location of a lighthouse in a designated space of heather and air, through which the sea-birds are still flying.”

***

Impossible to imagine a lighthouse without including the sea. They are a single entity, but also opposites.

The sea stretches out to the horizon; the lighthouse points to the sky.

The sea is in constant motion; the lighthouse is a static watchtower.

The sea is changeful, a “battlefield of emotions,” as Virginia Woolf might put it. The lighthouse is a stoic, immovable man.

The sea attracts by its distant sound, beyond the dunes. The rays of the lighthouse call out through mist and high tides.

The sea is a primeval liquid; the lighthouse is solidity incarnate.

The sea, the sea, is a biological, mythological metonym for the feminine. The lighthouse is masculine, phallic.

The sea is the empire of nature. The lighthouse is the artifice that, in its dignified smallness, opposes nature.

Excerpt from On Lighthouses © Jazmina Barrera. By arrangement with the publisher. Translation © 2020 by Christina MacSweeney. All rights reserved.