With a heavy heart, I mourn the loss of my great professor and dear friend, poet Dr. Refaat Alareer, who was killed with a number of his family members by an Israeli airstrike on his sister’s home in Gaza on December 6, 2023.

Refaat was a professor of English literature at the Islamic University of Gaza for more than fifteen years, during which he taught thousands of students. His influence on the person I am today is immeasurable. I met him in 2017 when I was just a shy student, reluctant to speak in front of an audience, especially in English. He encouraged me to read my poems aloud and write short stories that he helped publish with Novell Gaza, the American Friends Service Committee, and other outlets. He believed in me more than anyone else and more than I believed in myself. He wrote my recommendation letters to both Almeria University for an Erasmus exchange program and to the American University in Cairo for a master’s degree in English and comparative literature. I became a teaching assistant at the Islamic University of Gaza because of his support and encouragement, and he helped me work as a researcher on an international project on gender violence in Palestinian folklore in partnership with Glasgow University and Culture for Sustainable and Inclusive Peace (CUSP). This project, which started in early 2022, was supposed to be finished and published by December 2023. However, Israeli warplanes killed Refaat before he could see the project come to light, and thus, the project remained incomplete.

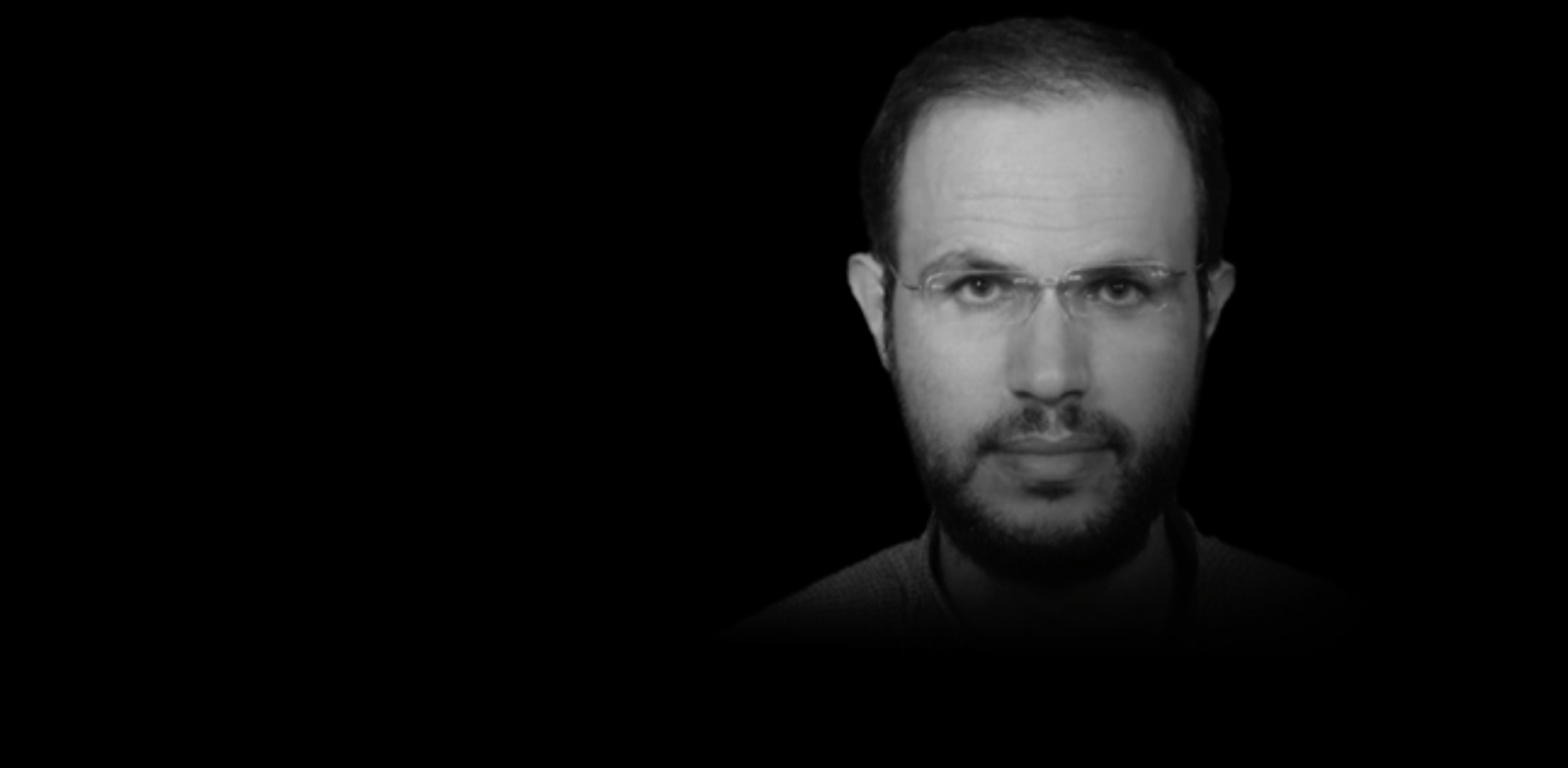

Dr. Refaat Alareer and students pose for a photo against a row of lush green hedges at Islamic University of Gaza.

For Refaat, teaching was more than just a job; it was a dynamic and transformative experience for himself and for his students. He wanted us to leave the classroom with a new pair of eyes, and with an exciting idea that we could take home and and contemplate for hours and days. He always encouraged us to share our newly developed thoughts with our friends and family, and to make note of their responses and counterarguments. One of his favorite activities at the beginning of each course was to rewrite a short story from the perspective of a different character, preferably the antagonist, or the least likable figure. In addition to achieving teaching outcomes like stirring the imagination and improving creative writing skills, this activity helped us deconstruct dominant narratives. It allowed us to extend our empathy, and to see the human in the outcast and the villain. Refaat was very biased in his love for Shakespeare; he read him with the passion and enthusiasm of a stage actor and he encouraged us to do the same. He particularly liked Shylock’s soliloquy, from The Merchant of Venice, and used to hold a competition for students to perform it: “Hath not a Jew eyes?” “If you prick us, do we not bleed?” He used to ask us if we, as Palestinians, identified more with Shylock, the oppressed Jew, or the Christian characters. Our answer was always Shylock. Refaat taught us about the Holocaust and the danger of anti-Semitism. He wanted us to be aware of the struggle of different oppressed nations and extend our solidarity to them. He always asked us to correct ourselves when we confused Zionism with Judaism.

Refaat was very supportive of the youths who passed through his classroom. He believed in us and helped us discover our potential. He saw students as the real changemakers in Palestine. He was patient with us, giving us time to grow, to make mistakes, and to improve, and he carefully guided us as we did. I don’t recall him ever dismissing anything that a student had to say in class as useless or too mundane, even when we, the student’s classmates, were not patient enough to listen to the end. He was adamant about our creativity. He always asked us to write a story or a poem as part of the course assessment or to improve a grade, then tried to publish as many of our works as possible. Refaat was always thinking of his students and coming up with different initiatives to connect us to the world. The blockade on Gaza made it next to impossible to have visiting professors or writers come and share their knowledge with us. Refaat broke down this barrier by organizing online sessions every semester, using his connections to host guest professors, speakers, and activists from around the world.

His care for his students didn’t end when they graduated. He always recommended us for jobs, projects, and scholarships, going above and beyond to get many of his students employed. He disliked wasted potential and wanted to see us financially independent in a country with one of the world’s highest unemployment rates. For example, while it is customary for only a single student to be appointed as a teaching assistant each year in the Department of English at the Islamic University of Gaza, when he was the department’s vice chair, he helped appoint five graduate students as TAs, and I was one of them.

Nothing I write could do him justice or communicate how great of a teacher, friend, poet, and activist he was. He was very strong and very stubborn. I always believed that people like him never die . . .they somehow transcend death and pain and come back to us as a source of hope, strength, and belief. In a way, we already see how far-reaching his words are now. His poem “If I Must Die” has being translated into more than two hundred and fifty languages, and his verses are chanted at protests all around the world. As we navigate the waves of sorrow at losing him, it is important for us to remember that he was targeted because of his words and his message and that it is our duty to carry it and amplify it. After all, he told us: “If I must die,/ You must live,/ to tell my story.”

© 2024 by Nadya Siyam. All rights reserved.