This interview is part of a series produced via a partnership with the George Town Literary Festival, an annual literary festival taking place this year between November 24 and 27 in George Town, Penang, Malaysia.

Eric M. B. Becker (EB): You speak in the introduction of how you were seeking to create an anthology of “witness poems and essays” rather than “protest” or “resistance poems.” Can you tell us a bit more about this decision? Were there other anthologies of witness poetry that you looked to as a guide when you decided to compile Picking Off . . . ?

ko ko thett (KKT): Many thanks for the interview, Eric.

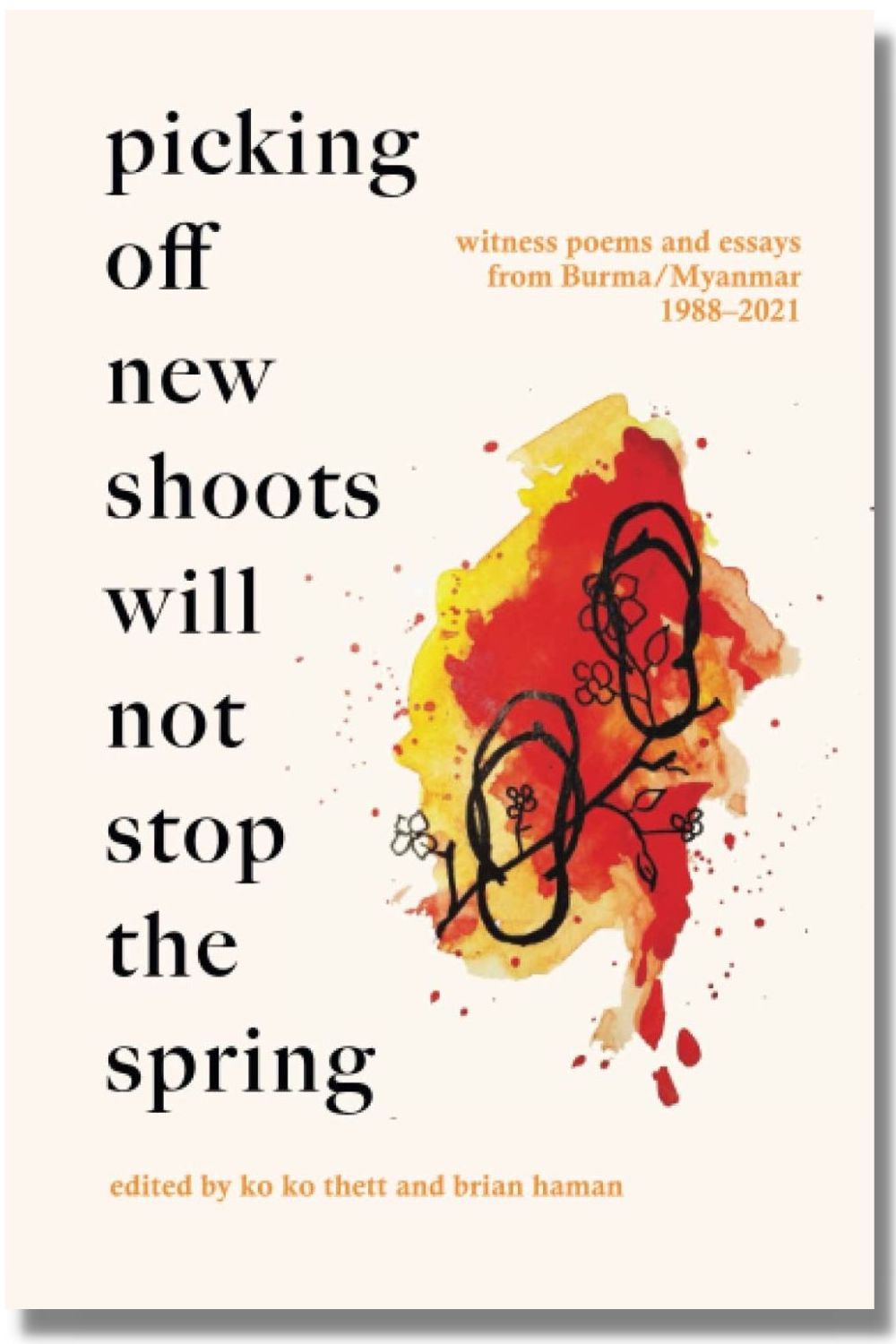

We must start with the title of the anthology, Picking Off New Shoots Will Not Stop the Spring, a protest slogan out of the 2021 Myanmar Spring. The Burmese protesters may or may not be aware that they are alluding to “You can cut all the flowers but you cannot keep Spring from coming” by Pablo Neruda.

Resistance poetry or protest poetry may be as old as Marxian revolutions. It must be The Witness of Poetry, a 1983 collection of essays by Czeslaw Milosz, that put the witness poetry on the map. To Milosz, who was subject to the twin totalitarianisms of the twentieth century, Nazism and Communism, poetry is not alienated or confessional but witness to events occurring to one’s community.

My coeditor Brian Haman and I took the argument a step further to say that witness poetry can be distinguished from protest poetry in that the former doesn’t necessarily have a collective political agenda. Witness poetry is subjective and individual as opposed to protest poetry. All protest poems may be considered witness poems but not all witness poems are protest poems.

In my opinion the distinction is quite crucial because contemporary mass social movements, even in Myanmar, comprise a multitude of issues, from gender to labor. Different individuals are engaged in resistance for different personal reasons, not with a common ideological goal. The only common goal they have may be to topple the junta and restore democracy. A good example of a witness poem would be a eulogy by a father who wrote about his son, who was shot dead by security forces in Yangon.

EB: Can you give us a look into the selection process? Given the situation inside Myanmar, was it difficult to locate work?

KKT: It wasn’t difficult to locate work. People began to voice very clearly and loudly, some more articulate than others, against the Myanmar coup soon after it happened in February 2021. They usually published on social media, and the internet was not shut down by the junta in the first few weeks of the protests. And there are online Burmese language journals such as Moemaka, edited out of the Burmese diaspora.

In fact we conceived the project after we noticed an overwhelming number of quality witness writings online. We thought we must preserve them in a durable format, not least in memory of those who were killed in protests.

The challenge I had, as an initial reader in Burmese, given the abundance of work, was winnowing out some writings. It was painful because I wanted everyone’s voice to be heard. We tried our best to balance between the number of established authors and that of what I call “participatory poets and writers” who usually wrote for social media.

EB: What was the reception, if any, to the anthology inside Myanmar? What risks did contributors take (if any) by participating in the anthology?

KKT: Due to safety concerns the hard copy of the anthology remains to be distributed in Myanmar. And very few Burmese people read English. I have no idea how the book will be received in the country. The reviews outside the country have been very positive though the case of outlandish Myanmar doesn’t get as much attention as Iran or Ukraine in the mainstream media.

Contributors inside Myanmar took considerable risks in participating in the anthology. A number of known writers adopted pseudonyms. There are also works by poets and protesters who were murdered by the security forces in the protests or in custody. There are also works by authors who have been jailed since February 2021.

EB: Can you describe the so-called Transitional Period between 2010 and 2020, when Myanmar was between military dictatorships, in terms of what that period meant for writers?

KKT: Since what was then Burma became independent in 1948, the country enjoyed press freedom until 1962, when the first military putsch ended parliamentary democracy. The 2010s were a decade when the military-led government cautiously lifted some of the censorship it imposed on the country since 1962. The decade also coincided with the arrival of the internet and smartphones. Myanmar people took to social media like fish to water as if the internet was social media. Social media became a vehicle for hate speech as well as environmental campaigns.

There was a burgeoning of new books, journals and new creative ideas enabled by the new-found freedom. Many of the bestselling books in that period were reprints of political tomes from the 1950s that were banned from 1962 to 2010.

In Myanmar poetry, there used to be only one national trend everyone followed in the past—anticolonial khitsan movement in the 1930s, social realist sarpaythit in the 1950s, khitpor and modern movements in the 1970s, etc. In the 2010s however the smartphone generation smashed that hegemony as they began to experiment with new types of poetic imports, from Flarf to deep image. The decade was a very exciting time to be a Myanmar poet. And yet a number of writers were jailed for irking the authorities in the so-called Transitional Period.

EB: What has happened to some of these important writers who were long persecuted by the dictatorship that lasted until 2010 and are now living under yet another?

KKT: Most of the writers in the country must lay low these days. Conflict is widespread, rule of law is nonexistent, and political murders are daily news. A number of lawyers have been jailed for representing dissidents. A number of publishers have been forced to shut down. Writers such as Ma Thida and San Nyein Oo have managed to leave the country in their own different ways. Poet Maung Yu Py was jailed for anti-coup protests in March 2021 and released in September 2022. A number of poets died fighting. Their works are featured in the anthology.

EB: Governments may censor writers or, as in two cases you cite in your introduction, simply eliminate them. On the other hand, there are often underground channels through which poetry and other work can circulate. What is the case in Myanmar?

KKT: In the 1990s I was a samizdat poet at a Yangon campus. Even under a most repressive censorship regime or even in a most watched jail cell, writers and artists will find channels to express themselves. Some poets have written on prison walls with their thumb nails. These days the internet is an obvious channel, but the authorities also know how to use technology to crack down on dissent. In contemporary Myanmar, as Burmese author Wendy Law-Yone observes, there is no writer who has been jailed for their publications. Writers, especially poets, have been jailed or killed by the junta mainly because they were in the frontlines of anti-coup resistance.

Read the poem “Spring” by Nga Ba and translated from Burmese by ko ko thett, originally published in Picking Off New Shoots Will Not Stop the Spring.

ko ko thett’s comfort zone is Burmese, but he also enjoys the discomfort of English, a language most of which he learned, and is still learning, as a poet. He has published and edited several poetry collections and translations and flown to a decent number of literary events, from Sharjah to Shanghai. His poems are widely translated, and his translation work has been recognized with an English PEN Translates Award. ko ko thett’s most recent poetry collection is Bamboophobia (Zephyr Press, 2022). He lives in Norwich, UK.

Copyright © 2022 by Eric M. B. Becker. All rights reserved.