What is a language museum? Although language is central to human life, most people wouldn’t consider it a subject for a museum exhibit. It is only recently that museums have begun to approach language as a valuable topic of display per se. But how to describe, analyze, and exhibit language and language diversity in a museum? Given their oral and abstract nature, languages are particularly challenging to exhibit physically in museums—how then to tell the story of our most precious forms of intangible cultural heritage in a tangible form?

While academic language societies have existed for centuries, and several institutions dedicated to individual languages or to major figures in the development of national languages were created in the nineteenth century, the establishment of language museums is a phenomenon of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. The almost eighty language museums that exist today in Africa, Asia, Europe, and North and South America have different origins, contents, visions, and missions. The Canadian Language Museum’s mandate, for instance, is different from that of the Museum of the Portuguese Language in São Paulo or the National Museum of World Writing soon to be opened in Seoul. Yet several of these language museums share a preoccupation with issues arising from borders and classification.

Planet Word in Washington, DC, is the most spectacular language museum to have opened recently (it was inaugurated during the pandemic in 2020, closed, and then reopened in 2021). The museum’s stated mission is “to inspire and renew a love of words, language, and reading in people of all ages,” and its motto is “the museum where language comes to life.” Indeed, Planet Word is deeply immersive (not to mention fully voice-activated), and within its walls one immediately feels its curators’ enthusiasm and eagerness to share the wonders of language. Along three floors in the exquisitely renovated Franklin School building in Northwest Washington, the museum celebrates language, sparks the audience’s curiosity, and amuses and surprises visitors with core facts about language. The celebration happens even in the restrooms: in 2021, the museum was nominated for the America’s Best Restrooms contest for “showcasing how to ask, ‘Where is the bathroom?’ in multiple different languages, illustrating the many names for animal waste, [and] poking fun with euphemisms and synonyms”

Most of Planet Word’s exhibits engage visitors through multimodal interaction: spatial, visual, vocal, audio, and tactile. “It is a museum built on ideas and turned into experiences,” explained the museum’s CEO and founder, Ann Friedman, in an interview this summer. Planet Word is museum as activity rather than as container. The dazzling use of cutting-edge technology plays, to be sure, a major role in Planet Word’s celebration.

Each of the museum’s three floors hosts several exhibits, which invite visitors to experiment with various aspects of language. “Word Worlds,” for instance, is an interactive electronic painting exhibit in which younger visitors can use digital paintbrushes to change landscape and cityscape murals by choosing adjectives like “nocturnal,” “crepuscular,” and “surreal.” The sound, color, and motion of the scenes transform as the brush is dragged along the wall, reflecting some of the meanings and associations of these adjectives. Another highlight, “Unlock the Music,” is a popular karaoke-style room with friendly explanatory songwriting techniques for all ages. And in the “Words Matter” gallery, multiple videos tell the intriguing and often moving personal stories of various speakers as they reflect on aspects of language that have impacted their lives. Their storytelling, no less than their specific stories, powerfully foregrounds the elaborate ways in which language, stories, and lived experiences are deeply intertwined. Visitors who are so moved may record and share their own messages.

“We won’t tell you what’s right or wrong. We’re just here to celebrate the power, fun, and beauty of language.” This is one of the museum’s guiding principles. It’s particularly visible in exhibits like “I’m Sold!”, a well- designed and entertaining (especially if experienced in groups) gallery involving a series of screens in a spiral that delve into the language of marketing and advertising. Visitors are invited to learn about the bouba/kiki effect (and the relationship between shapes and sounds) and play with double meanings, provocations, puns, spoonerisms, and pragmatic implications, among other persuasion techniques. Rhetoric is the theme in the “Lend Me Your Ears” exhibit, in which visitors can watch and analyze famous speeches delivered in English—and even perform one using a teleprompter.

The “I’m Sold” exhibit on the first floor

Even before entering the museum, visitors are greeted not by a reproduction of the Tower of Babel or the Rosetta Stone, but by the immense “Speaking Willow” sculpture created by the Mexican artist Rafael Lozano-Hemme. This interactive sculpture—made of aluminum, speakers, electronics, LED lights, computers, SD cameras, and patch bays—is triggered whenever visitors walk under the tree’s branches/speakers, which release a chorus of 364 murmured language recordings. The label next to the sculpture explains, in English only, that “‘Speaking Willow’ celebrates the world’s interrelated linguistic diversity.”

Linguistic diversity is also the theme of “The Spoken World” exhibit on the third floor, where the museum recommends that guests begin their visit. In this magnificent space, iPad stations offering interactive videos are scattered around a twelve-foot-tall LED globe suspended in the middle of the Great Hall. In these videos, native speakers of thirty-one different spoken and signed languages of the world teach visitors about a unique feature of their language and invite them to pronounce or sign a word. The Quechuan language ambassador, for example, speaks about the Quechua language’s particular way of talking about time; the Hawaiian language ambassador explains Hawaiian’s use of vowels and the meaning of the name of their state fish; the Spanish language ambassador coaches visitors through rolling their Rs; and the Hebrew language ambassador explains the origin of the Hebrew word for “ice cream.”

Museums are not neutral, and language museums are no exception. These institutions make crucial choices about who and what get space, visibility, and resources, and which topics and perspectives are foregrounded. “The whole purpose of this museum,” Friedman stresses, “was to focus people’s attention on words, which I consider to be the overlooked, underappreciated, disregarded little artifacts of our lives.” The twenty-first century, she adds, “is the time when a museum can highlight words and language.” What words and language, then, are being highlighted at Planet Word?

Along the three exhibition floors, visitors can learn about topics ranging from aphasia and word taboos to constructed languages, dialects, and rhythm in poetry by engaging with voice-activated beacons. These beacons communicate through written texts, sound, photos, videos, and graphics. The beacons’ presentations, as well as the “First Words” exhibit on language acquisition, are shaped around clear and precise core questions that successfully entice the visitor: “How do we learn to speak our first language?”, “Do animals have language?”, “Is there a correct way to talk?” It is not always as clear, however, where the knowledge provided in the museum’s answers comes from. Planet Word often glosses over the contributions of linguists to these topics, and the role of different theories and perspectives in several of its answers.

The balance between the individual and the collective—and, in the case of languages, between universality and diversity—is always a hard one to strike. What story does “The Spoken World” (the exhibit on language diversity) tell us about languages? There are no written labels in this gallery, no clues regarding the choice of languages represented in this striking space, or any contextual information about the speech communities to which these individuals belong. Nor does the museum, in this exhibit or otherwise, address the various perspectives on what “a language” is (as opposed to language per se). A language may be defined in different ways according to different theories, whether by Saussure, Chomsky, Bloomfield, or Trubetzkoy, for instance. Is a language a discrete entity? Are languages marked by a border that ensures unity, like the boundary of a nation, or are they borderless? “The Spoken World will make clear our shared humanity,” the museum’s website explains, “and our responsibility to respect and seek to understand each other.” It is, admittedly, a beautiful exhibit, especially when the Great Hall is full of people and the multilingual voices echo across the gallery.

And yet in its mission to help visitors “respect and seek to understand each other,” the exhibit could broaden its scope, creating space for reflection on the asymmetrical power relations between languages, raising critical questions about endangered and indigenous languages, and promoting a better understanding of minority languages. It could include relevant discussions of Spanish that acknowledge the voices of more than forty million speakers of Spanish in the US, with all their variants of rolling Rs. This type of expansion could open up new possibilities for negotiating the intricate relations between cultures and languages. It could generate fruitful discussions about the importance of cultural heterogeneity and encourage conversations about speech communities and linguistic rights. Such expansion, furthermore, would be consistent with the founder’s core commitment to a strong democracy and her vision of Planet Word “as a museum for the entire community.”

At the moment, Planet Word orbits around the English language and is geared toward an Anglophone audience. The museum does not yet cater to multilingual visitors: there are no translations of the exhibits’ contents into other languages or other materials available for non-English-speaking audiences. Sign language interpretation is offered in the public speaking gallery (there is the option to give a speech in ASL) and most of the galleries and interactive exhibits include open captions.

Translation, however, is intrinsic to the use of language. And despite their invisibility at Planet Word, translation and transfer in their many forms—intralingual, interlingual, intersemiotic—are nonetheless very present in the museum. During my repeated visits, I noticed a lot of cross-linguistic and intercultural interaction. In fact according to an interactive multilingual display on the first floor speakers of more than 926 languages have visited the museum in the past two years. As a whole, Planet Word can be described as a “translation zone” where different speech communities meet and intense interaction and negotiation take place across languages and cultures.

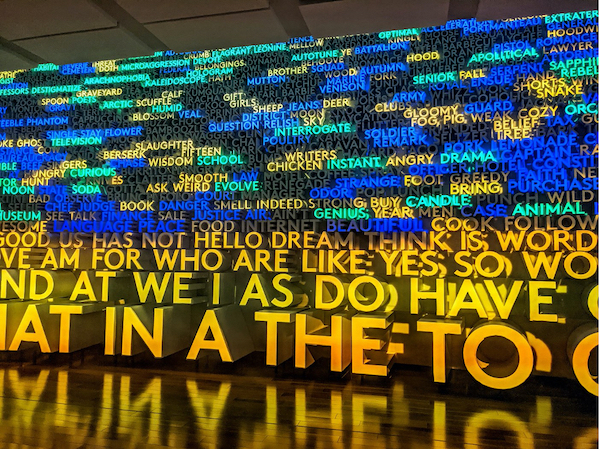

As for “highlighting words,” as Friedman put it, more than a thousand three-dimensional words are highlighted in the impressive exhibit “Where Do Words Come From?”, whose massive, twenty-foot-tall talking wall tells the story of the English language. The immense artifact interacts with the audience by asking questions and responding with a mesmerizing combination of sound, light effects, and animation. I found particularly interesting the contrast between the presumably solid, fixed, stable material of the “wall,” on the one hand, and the fluidity and movement of the words projected on it, on the other. The wall does a wonderful job of showing the fusion and friction of the various linguistic layers that make up the English language. It celebrates, in a fun and specific way, the cross-fertilization with other languages that was essential to the development of English, thus revealing its irreducible hybridity (and, by extension, that of other languages). This linguistic friction, however, is certainly not just fun.

The 20-foot-tall wall of words in the “Where Do Words Come From?” exhibit

Words, as we know so well in the US today, can be used to harm, divide, and kill. With some modifications, Planet Word’s talking wall could be made more vociferous against prejudice and racism. As an instrument to understand more deeply how words are involved in social, economic, and politic inequalities, it could acknowledge more forcefully the diversity of its audience and highlight the many Englishes that exist, celebrating both national and international variances and change. The wall, like the museum, is still very young. I feel strongly that Planet Word will have a more transformative impact on the future of the community it wants to serve when it makes the effort to speak out in multiple voices and become more deeply representative of its various speech communities.

Museums can be agents of change in society. A strong driving force behind this monumental project by Ann Friedman is literacy. A former language-arts teacher, Friedman believes that “being literate is essential to a strong democracy.” Planet Word “strives to have a measurable impact on literacy outcomes,” and the exuberant library on the second floor epitomizes this core value more than any other space in the museum. In this grand, dimly illuminated room packed with books from floor to ceiling, visitors can pull forty-nine titles from the shelves—from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll and Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi to Haroun and the Sea of Stories by Salman Rushdie and The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank—and lay them on special cradles with RFID chip readers. When the book is opened, an overhead projection animates a spread of pages and recounts a selected passage or offers a comment on the book by the author or a famous reader. There is also a marvelous “Poetry Nook” with seventy-five minutes of poetry videos and nine delightful voice-activated dioramas of classic children’s literature.

The magical library

“How do we get America reading again? How do we create buzz around words and language?” Friedman asks. I am not sure about “getting America reading again” and some of the assumptions that entails, but there is no doubt that Planet Word is an extraordinary place creating a fantastic buzz around words and language.

Copyright © 2022 by Tal Goldfajn. All rights reserved.