The Wanderer

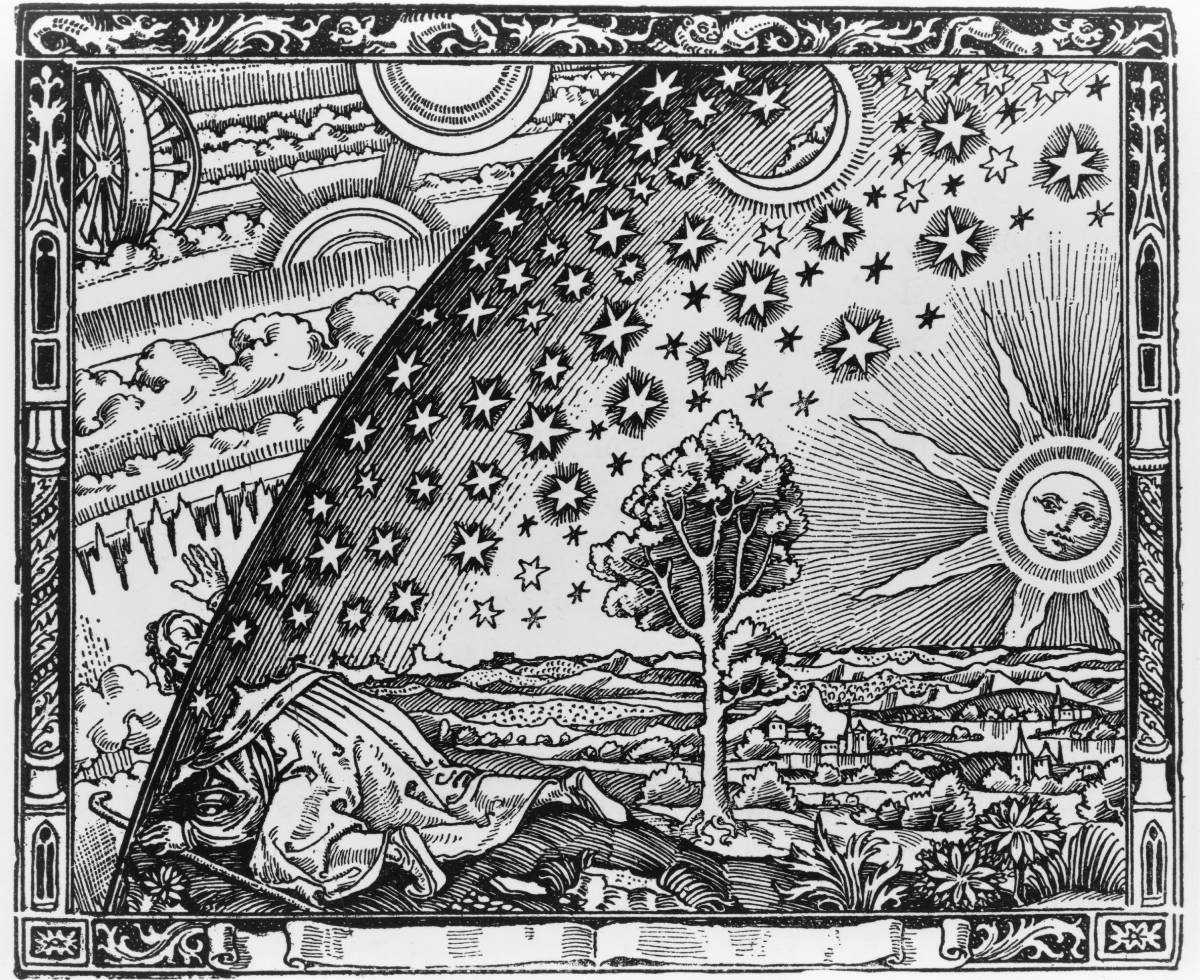

I’ll start with a well-known engraving of unknown authorship, published in 1888 by French astronomer Camille Flammarion. It depicts a wanderer who has reached the limits of the world and who, peeking his head out beyond the earthly sphere, delights in a view of an orderly, harmonious cosmos. I have loved this wonderfully metaphorical picture since I was a child, and it reveals new layers of meaning every time I look at it, conceiving the human so differently from Leonardo da Vinci’s vision of the static and triumphalist Vitruvian man as the measure of the universe and ourselves.

In Flammarion’s version, we have man presented in motion, as a wanderer with a pilgrim’s staff, in a traveling cloak and cap. Although we cannot see his face, we can guess at its expression—a mix of pleasure, awe, and bewilderment at the harmony and magnitude of the world that is beyond what we can see. We can glimpse only a fraction of it from where we are, but this wanderer must be seeing a great deal more. Here we have clearly marked spheres, heavenly bodies, orbits, clouds, and rays—the almost inexpressible dimensions of the universe that no doubt get more and more complex, into infinity. The wheeled machines shown in the top left corner that frequently used to accompany angelic beings in illustrations of Ezekiel’s visions are yet another symbol of incomprehensibility. On the other hand, behind the wanderer’s back, there is the world, with nature represented by a massive tree and several other plants, and culture by a city’s towers. All that seems fairly conventional and banal, not to say boring. We may assume that what we are seeing in this engraving is the final moment of the wanderer’s long journey—he has succeeded where so many have failed: he has arrived at the ends of the earth. Now what?

My impression is that this mysterious engraving of unknown provenance is the perfect metaphor for the moment in which we have all found ourselves.

It’s a Small World

It’s shrunk considerably in the past century. We have blazed trails through it, made its rivers and forests our own, hopped across its oceans. Many of us can feel the finitude of the world. This is likely a derivative of the reduction of distances through globalization, and of the fact that just about any place on Earth may be gotten to, if one has the resources. And of how easy it is to learn about it—these days anything can be checked online, and communicating with anyone is quick and simple.

This is without a doubt a new historical experience of being human, and I’m curious who the first person was to have this sense that the world is ultimately a trifling thing, easily dealt with. Perhaps it was one of the new generation of businessmen, someone who “trades in hot air,” as the Dutch say, that Mr. Buy-Low-Sell-High who is eternally in motion, flying from continent to continent with a passport from some well-off nation. Morning in Zurich, evening in New York. Over the weekend he pops over to some tropical island, where he dreams marine dreams and sharpens his senses with cocaine. Or perhaps someone completely different—someone who has never set foot outside his county lines but has just bought his child a toy manufactured in some distant land, produced by people of whose existence he was totally unaware until this moment. The toy looks friendly and familiar, however, concealing its exotic qualities in a universalized shape.

In this new experience of the smallness of the world, some role must be played by triste post iterum, the post-trip sadness we experience when we come home after the intense experience of a long journey. It seems we reached some limits or experienced something we couldn’t have had we not been born in an era in which travel had turned into something more than a privilege or a curse, namely, an adventure. Then, setting down our suitcases in the entryway, we ask ourselves: Is that all? Was that it? That’s what all the fuss was about?

We’ve been to the Louvre and seen the Mona Lisa with our own eyes. We’ve climbed the Maya pyramids in the hopes of experiencing the drama of the passage of time that mercilessly destroys the creations of thousands of years. We have basked at Egyptian or Tunisian resorts, dining upon diluted ethnic cuisine that pleased everyone without exception. The Mongolian steppes, India’s crowded cities, the views from the sky-high Himalayas…

Even if we have not yet managed to see this or that, nonetheless up until the pandemic we lived with the awareness that traveling to places that we hadn’t seen before was viable—they were listed in the travel agencies’ brochures, where they were termed “destinations.” The world was within range, getting anywhere was possible, so long as we got together the money for it.

For the first time in our history, people are experiencing this overwhelming finitude of the world. In the evenings we watch the lives of others on the screens of our smart devices, watching people with whom just a hundred years ago we could never have crossed paths.

Observing them from a distance, we see that the repertoire of roles and possibilities is also finite, and that in fact people are similar to one another, more so than it might have seemed to our ancestors. They, as we remember, let their imaginations run wild as they described with glee the peoples inhabiting the antipodes that so excited former travelers.

Today thanks to television series, film, and social media, everyone knows that people from overseas lands do not have many heads or just one leg with a big foot or a face on their chest, and although they may differ by skin color, height, or certain customs, those differences vanish into the background of a whole host of similarities. Others function similarly to us in our cities and countries, languages and cultures. They love, miss, desire, fear for the future, have trouble with their kids. On this fundamental similarity is based the enormous popularity of the latest invention: streaming platforms.

The traveler sees that everywhere is similar, as well—that hotels exist, that people eat off dishes, bathe in water, purchase souvenirs and presents for their loved ones, and even these are homogenized by the fact that in spite of being imitations of local craftsmanship, the majority are made in China.

We know, too, that from just about anyone on Earth we are separated by no more than six other people (along the lines of: I know someone who knows someone who knows this person who knows X, etc.), and from the time of Christ by only about seventy generations.

It used to be that the world was vast and unimaginable—now imagination is no longer useful to us, we have everything at our fingertips on our smartphone. There used to be blank spots on the carefully prepared maps of the world, fueling the imagination and acting as a warning to human hubris. When preparing for a journey, people assumed they would never return. Setting out, preceded by the drawing up of a will, was a limit event that began a process of initiation, a process of transformation, the result of which could neither be known nor well understood.

Paradoxically speaking, we lived in a world that was open to imagination, a world with barely sketched borders, filled with the unknown. That world demanded new stories and new forms, it shapeshifted ceaselessly, ceaselessly being created before our very eyes.

Today the world fits into our calendar, our watch. We can conceive of it, it fits within our imagination. Within three days, we can be anywhere we want (with a few uninteresting exceptions). The blank spaces on the maps have been filled in hermetically by Google Maps, which with vicious precision shows us every backstreet. In addition, it is more or less the same everywhere—the same things, artifacts, ways of thinking, money, brands, logos. Being exotic or unique is a scarce commodity, more and more it disappears from everyday life and becomes a gadget. Like in a Baltic resort where an entire Thai restaurant has been imported from Thailand, or in the lowlands of Central Europe, where a gigantic complex was set up in imitation of the tropics.

Thanks to the device that fits in your hand or on your lap, you can at any time talk with family thousands of kilometers away, in a different climate classification, at a totally different hour and even a different season. A tourist on an expedition in Tibet can connect in a few seconds with home in Skaryszew or Schenectady. People who would never have had the chance to meet can now be in touch through social media.

To our five senses the world has become—again—small. On the other hand, it is breathtaking to see the globe in a picture from space taken by a human being. A little blue-green orb dangling in an abyss. For the first time in history, we can perceive our planetary place—as finite and limited; fragile and prone to ruin.

Added to this is the feeling of being crowded, of finite space, crampedness, the constant presence of others—the feeling of finitude in experiencing the world becomes claustrophobic. No wonder that we’ve been dreaming more and more lately about trips in outer space, about leaving our old home, which has turned out to be too familiar, too tight, too cluttered.

This perception of the reduction and finitude of the world is intensified by being online and widespread surveillance. Yes, yes, we are already living in the panopticon—we are constantly being seen, watched, and analyzed.

The feeling of finitude makes everything banal, since only what does not yield to our understanding can awaken our enthusiasm and retain the wonderful status of mystery.

Sesamicity

Yet we frequently treat infinity as chaos, since it does not give us the chance to apply any cognitive framework, any structure to it. There are no maps of infinity. It also rejects man as its measure.

If a person should want to commune with infinity once more, then it’s enough to go online. Here, the overwhelming feeling that there is too much of the world teaches a certain cautious resignation—I’ll just go on my way, learning to ignore the curiosities that beckon on the side of the road, like Lot fleeing a burning Sodom with enough willpower not to turn around and look back, unlike his overly curious wife.

Let’s call it Lot’s Wife’s Syndrome now whenever we get stuck in front of our screen—a kind of contemporary catatonia. This syndrome affects millions of teenagers and incels who, particularly during the pandemic, despite warnings, have looked at the burning cities and been unable to tear their eyes away again.

Surfing in search of some bit of information, I have often had the feeling that I was swimming in a vast ocean of data that was furthermore constantly in the process of self-formation and self-comment. Whoever was the first to term such an activity “surfing” was really a genius. The image of the lone person who, with the aid of a modest board, soars on the summit of a wave across a furious ocean is very much justified here. The surfer is transported by the element, and he himself has only a limited influence on his trajectory—he relies on the energy and movement of the wave. Let us note that this sense of being merely the object of motion that does not depend on us, and thus in a certain way of being guided, dragged along by the force of some mysterious inertia, resurrects the old idea of fatum, which we now understand differently—as the network of dependencies on others, as inheriting patterns of behavior not only in the biological but also in the cultural sense, the result of which is a lively and likely still developing discussion of identities.

Infinity burst in on the world of Homo consumens when that world began to be reminiscent of a hidden treasure trove. We said, “Open, Sesame,” and—lo, it is done! The trove is wide open, overwhelming us with the wealth of services offered, of goods, types, patterns, varieties, cuts, styles, trends. Everyone has likely experienced at least once this fairy-tale multiplicity of offerings, along with the disturbing suspicion that we would need several lives to take full advantage of them all.

It also isn’t clear how our lives were reduced to the acquisition of new goods, the purchasing of services from out of an inexhaustible array. In a story by the brilliant Philip K. Dick, factories controlled by some mad intelligence cannot stop production and must create for the infinite number of planned goods an ideal buyer, a superconsumer hypnotized by this cosmos of goods, a client for whom life will be trying and savoring variations of this or that, deliberating over lipstick brands, gadgets, perfumes, clothing, cars, toasters, aided by special shows and magazines that the superconsumer can consult on what to choose. This vision, so futuristic in the 1960s, has come to fruition faster than we thought. Today it’s a description of our here and now.

And yet the same is true for the consumption of intellectual goods. The resources of virtual libraries have become infinite—sitting at a computer, one really has the impression that man is maneuvering through an opened trove that can no longer be grasped—not the authors, not the titles, not the entries. It’s shocking to know that as I write these words, hundreds, if not thousands, of articles, poems, novels, essays, reports, and more are being written. Infinity reproduces itself by itself, spreading, and we attach to it the fragile tools of search engines in order to maintain the impression that we’re still in control.

My generation is dealing with this particularly badly—after all, we were raised during a time of scarcity and outright lack, many of us retain an instinct for stockpiling in case of crisis, inflation, and the like. This is why my husband collects newspapers and still cuts out clippings, while at the same time, with a Noah-esque sense of mission, he builds bookshelves for paper books.

Our generation and previous generations were trained to tell the world: YES, YES, YES. We kept repeating: I’ll try this and also this, I’ll go there and then there, I’ll experience this as well as that. I’ll take this, and what’s the harm in taking that one, too?

Now alongside us there is a generation that understands that the most humane and ethical choice in this new situation is learning to say: NO, NO, NO. I will give up this and that. I will limit that and that. I don’t need that. I don’t want this. I will let this go.

My Name is Million

One of the most important discoveries of recent years—among the discoveries that have made an impact on our very perception of the essence of man—was without any doubt the assertion that the human organism, like plants and animals, interacts with other organisms in its development and functioning—that organisms are linked by an absolute interdependence. Thanks to findings in biology and medicine—beginning with the groundbreaking ideas of Lynn Margulis, according to whom the driving mechanism of evolution and the formation of species was symbiosis, the interconnectivity of organisms, and continuing through the results of contemporary research—it has turned out that we are more of a collective being than an individual one, more a republic of many different organisms than a monolith, a hierarchically structured monarchy. “Your Body Isn’t All YOU: Only 43% of Your Cells Are Human,” proclaim the headlines in the popular press, likely instilling real anxiety in many. No matter how often you bathe, your body remains covered in populations of “neighbors”—bacteria, fungi, viruses, archaea. The majority dwell in the gloomy recesses of our insides. The current coronavirus pandemic further confirms this notion that would seem to come straight out of a horror movie—mankind may be colonized en masse. It sounds both unlikely and totally revolutionary, since until now philosophy and psychology have monadized us. The monadic man, an individual being “thrown” into existence, towered alone over plant and animal kingdoms as “the crown of creation.”

This was the picture that dominated our imaginations and our self-perception. Looking in the mirror, we saw a thinking, self-aware conqueror, separate from the world, frequently lonely and tragic. A white man’s face appeared in the mirror, and for some reason, we all agreed that “man” had a magnificent ring to it. Now I know that that wonderful Homo sapiens is only 43% himself. The rest is made up of those absurd and insignificant little creatures that have thus far been easy to exterminate with antibiotics and pesticides.

Becoming aware of our dependence on other beings, and even of our biological “multiorganismicity,” introduces into our thinking in this organic way an idea of the swarm, of symbiosis, of cooperation.

I believe that the sin for which we were exiled from paradise was not sex, nor disobedience, nor even finding out God’s secrets, but rather considering ourselves to be separate from the rest of the world, to be individual and monolithic. We simply refused to be in relationships. We left paradise under the watch of a God who was equally separate from the world, monolithic, monotheistic (I can’t shake the image of a God in gloves and a mask), and from then on, we began to cultivate the values of that state: striving for mythologized integration, for totality, egoization, monolithic monism, analytic thinking, divisive, on the basis of either-or (Thou shalt have no other gods before me), a monotheistic religion, discrimination, valuation, hierarchy, fencing off, separation, sharp black-and-white divisions and, finally, a narcissism of the species. We formed a limited liability corporation with God that monopolized and destroyed the world and our conscience. Thanks to which we totally stopped being able to understand the astonishing complexity of the world.

The traditional perception of the human being is undergoing dramatic changes today, not only as a result of the climate crisis, epidemic, and the discovery of the limits of economic development, but also through our new reflection in the mirror: the image of the white man, the conqueror in the suit or the safari helmet, fades and disappears, we see in its place something like one of the faces painted by Giuseppe Arcimboldo—organic, highly complex, incomprehensible, and hybrid—faces that are a synthesis of biological contexts, borrowings, and references. Now we are not so much a biont as a holobiont, that is, a group of different organisms living together in symbiosis. Complexity, multiplicity, diversity, mutual influence, metasymbiosis—these are the new perspectives from which we observe the world. Blurring before our eyes, as well, is a certain important aspect of the old system, which has seemed fundamental up until now—the division into two genders. Today it can be seen increasingly that human gender is more along the lines of a continuum with a range in concentration of features, rather than the old polar antagonism between two. Everyone can find their unique and proper place here. What a relief!

This new perspective, based on complexity, sees the world not as a hierarchically ordered monolith, but as multiplicity and diversity, as a loose, organic network structure. But the most important thing is that, in this perspective, for the first time we begin to perceive ourselves as complex and varied organisms—this is what the discovery of the ideas of microbiota and the holobiont has led to, along with the discovery of their stunningly powerful influence on our body and psyche—on the whole of what we term human.

I suspect the psychological consequences of such a state of affairs will turn out to be surprising. Perhaps we will return to seeing the human psyche as made up of many structures and layers. Perhaps we will begin to treat personality as a kind of cluster, and will no longer fear thinking of multiple personalities as totally normal and natural. In the social sphere, perhaps there will be a new and proper valuation of decentralized structures organized in networks, while the hierarchical state based on the excluding idea of the nation will become totally anachronistic. Perhaps at last monotheistic religions, showing an overwhelming tendency toward violent fundamentalisms, will not be in a position to meet the changing needs of the people and will begin to “polytheize.” It would seem that ultimately polytheism suits the idea of democracy much better.

Today, that traditional, elaborate construction of man apart from the rest of the world is collapsing. I imagine it like the collapse of a massive, rotted tree. And yet the tree does not cease to exist, after all—only its status changes. From now on it will be a place of even more intense life: the germination of other plants upon it, its colonization by fungi and saprophytes, settlement by insects and other animals. The tree itself will be reborn out of its growths, seeds, roots.

Lots of Worlds in One Place

Likely never in history have the distances between generations been so vast. I am thinking about the deep gaps between generations, determined by the development of artificial intelligence and the avalanche of changes in the access to information. It would seem that human society has stratified into generational zones that differ from each other in terms of their approach to the world, to knowledge, the way of using and the quality of language, skills, mentality, type of political engagement and modes of life. Insofar as in a still very intensively globalizing world (up until the pandemic) the differences between cultures and ethnicities were gradually becoming blurred, so that everything began to resemble everything, the chasm between the generations grew. More and more clearly and louder and louder is the conflict between the old and the young verbalized, and this can be seen especially in the case of the pandemic, the effects of which are marked by the differences in the body’s resistance to the virus. But similar discrepancies had already occurred in the context of climate change and the need to prevent it. Here, too, the young acted against the old, rightly accusing them of a lack of long-term, forward thinking and a vision of recovery. That gap, however, is not just a conflict between old and young, but a kind of strange incompatibility of different age groups living in a single space.

The gap between grandchildren and grandparents is now greater than the former gap between New York and a little Polish city like Sandomierz. And the one between great-grandchildren and great-grandparents—here we would likely have to resort to interplanetary distances for comparison… Individual generations today have not only their particular languages, but also their own everyday rituals. They each have their own specific modes of consumption and distinct ways of life. They imagine the future differently, and rely upon the future in a different way, their relationship to the past is different, and they interact with the present differently, too. While grandchildren immerse themselves in ever newer apps, their grandparents watch their favorite shows on TV. Internet bubbles spread into the real world, which becomes particularly pronounced when it comes to seniors. It was a really remarkable experience for me to have these senior hours during the pandemic, when between ten and noon those over sixty-five went out into the streets and ran their errands in the different stores. Then, in the afternoon, the only people lining up in the supermarkets were thirty- and fortysomethings. The beginning of some sort of gloomy dystopia…

The breakdown of the population into generational tribes makes one realize how many realities coexist in the same space. They sometimes dovetail, overlap, affect each other, but they remain separate.

2020’s Strange Summer

Traditionally, great changes have followed cataclysms and wars. Apparently, just before the First World War, people had a feeling that it was the end of some era, some world. For many, the situation then had seemed unbearable, although they weren’t quite fully conscious of it yet. Today we can’t understand that enthusiasm that brought cheering crowds onto the streets to bid farewell to young men setting out for war. The brisk step of the soldiers, pumped up by the filming techniques of the time, which almost turned it into the prance of a puppet, led them somewhere beyond the horizon, where the trenches of Verdun and the Bolshevik revolution lay in wait. Their entire world order was about to slide into the abyss.

Let us not repeat their mistake.

Today, as 2020’s strange summer passes, we don’t know what will happen next. It seems that even the experts have stopped making predictions, not wanting to admit that they are like today’s meteorologists—unable any longer to predict the weather as a result of climatic turmoil.

The world around us has become too complex, and in multiple dimensions at the same time. The spontaneous, reflex response to this is that of the traditionalists and conservatives who treat this increase in complexity as a disease, as a disorder. As medicine, they offer us nostalgia, a return to the past and a clinging to tradition. Since the world has become too complicated, we must simplify. Since we cannot cope with reality, so much the worse for it. The longing for lost time shows up in our thinking, our fashion, our politics. In the latter, there is a belief that you can turn back time and enter the same river that flowed thirty or forty years ago. I don’t think we would fit into those lives we had then. We wouldn’t fit into the past. Not our bodies, and nor our psyches.

And if we were to take a step to the side? Beyond the well-trodden paths of the considerations, deliberations, and discourses, outside the systems of bubbles orbiting around a common center. To a place from which we could see better and more broadly, from where the contours of the broadest context are visible.

When Greta Thunberg called on us to shut down the mines, stop flying, and focus on what we have, and not on what we could yet get, I hardly think she was advocating for us to clamber back into horse-drawn carts and huts with hearths and smoke holes.

Undeniably, the pandemic turned out to be the black swan that—as happens with black swans—no one expected, the thing that will change everything.

My favorite example of the sudden appearance of the black swan is the events of late nineteenth-century London. People living in a tragically overcrowded and filthy city, thinking about the future, were worried that if traffic on the streets of the British capital were to continue developing so frenetically and rapidly, soon the heaps of horse dung would reach the second floor of every building.

Having initiated the search for solutions to this problem, plans for special gutters and dumps had already been patented, and satisfaction mounted with expectations of big businesses that would cart the horseshit out of town. And that’s when the car showed up.

Cognitively, the black swan may be a turning point, but not because it will bring about an economic crisis or make people aware of their fragility or mortality. After all, the results of the pandemic are many and quite varied. The most important one, however, or so it seems to me, is the fracture of the deeply internalized narrative that we control the world and are the masters of creation.

Perhaps man as a species must boast about the power he has had thanks to his reason or his creativity, and this leads him to the idea that he is the most important—he himself and his interests. But from another perspective, a different view, he can feel equally necessary as the important eye of a network, as a bearer of energy, and above all as someone who will be responsible for the whole of this complicated structure. Responsibility is a factor that allows us to maintain a sense of our importance and does not degrade the construct, built with great difficulty over many centuries, of the supremacy of Homo sapiens.

I believe that our life is not only the sum of events, but also the complex interweaving of meanings that we ascribe to those events. Those meanings create a marvelous fabric of stories, concepts, ideas, and can be considered one of the elements—like air, earth, fire, and water—that physically determine our existence and shape us as organisms. The story is thus the fifth element that makes us see the world in this, rather than in any other, way, makes us understand its infinite diversity and complexity, as well as organize our experience and pass it on from generation to generation, from one life to the next.

Kairos

The engraving from Flammarion’s work shows a kairotic moment. Kairos is one of those lesser gods who, in comparison with the Olympians, seem rather insignificant and who tend to flit off somewhere to the peripheries of mythology. He is a particular kind of god, and he has a particular kind of hairstyle. It is his signature—bald on the back of the head, with just one lock of hair hanging over his face by which he can be caught as he approaches; once he has passed, there is no way to grab him. He is the god of opportunity, of the fleeting moment, the incredible possibility that opens up just for a moment and that must be seized without hesitation (by the bangs!), so that it doesn’t pass you by. Not noticing Kairos results in missing an opportunity for transformation, metanoia—one that is the result not of a long process, but of a moment pregnant with possible effects. In the Greek tradition, Kairos defines time—not that mighty stream of it known as chronos, but rather exceptional time, the decisive moment that changes everything. Kairos is always associated with a decision made by man, and not with destiny or fatum, or external circumstances. The symbolic gesture of grasping Kairos by a lock of hair means reflecting that here comes a change, a reversal of the trajectory of fate.

For me, Kairos is the god of eccentricity, if by eccentricity we mean abandoning the “centric” point of view, the well-trodden paths of thinking and acting, going beyond areas that are well known and somehow agreed upon by communal thought habits, rituals, and stabilized worldviews.

Eccentricity has always been treated as a quirk, as marginal. And above all whatever is creative, brilliant, and moving the world in a new direction must be eccentric. Eccentricity means a spontaneous, and at the same time joyous, contestation of what is pre-existing and considered normal and obvious—it is a challenge to conformism and hypocrisy, a kairotic act of courage, seizing the moment and changing the trajectory of fate.

We’ve put off general knowledge and lost our sense of holistic perception somewhere. Before our eyes, the last scholars of true erudition are passing away—people like Polish authors Stanisław Lem or Maria Janion, capable of grasping the affinities of knowledge in areas seemingly distant from one another, great eccentrics who were able to peek outside the sphere of the agreed-upon order. Once, at least, we tried to comprehend the world as a whole, building its cosmogonic and ontological visions, asking questions about its meaning. But somewhere along the way we became compartmentalized in much the same way that the capitalist factory proletarianized artisans who could still produce a whole product, turning them into laborers making only one component of it, unaware of the whole.

The process of society’s self-division into bubbles is a process of an unimaginable, total proletarianization. We shut ourselves in and cushion our embubbled sphere of experiences, blocking our access to the lives and thoughts of others. In addition, we prefer it this way, we’re fine with it, and other people—the people whose understanding or even just whose notice would require of us stepping outside—don’t concern us much.

The public sphere does exist, of course—but more as a surrogate, an appearance, a game, a spectacle against the backdrop of threadbare decorations appropriated by the authorities and their rituals. In the well-trodden centers, the old sites of the exchange of ideas, there is no longer any air. The agora has been transformed into a collection of ruts and tracts along which we move mechanically. Universities have abandoned their proper roles, transforming into a grotesque pastiche of themselves—instead of creating knowledge and platforms of mutual understanding, they have shut themselves up behind their walls and portals, defending access to knowledge and jealously concealing the results of their research from each other. In competing for grants and lines on their CVs, scholars have turned into rival laborers.

Not seeing the whole, we remain dependent on local, individual segments of the great jigsaw puzzle that is the world—the given world, and the world we are building on top of it.

In what I write, I have always tried to steer the reader’s attention and sensitivity toward the whole. I’ve taken pains over total narrators, provoked with fragmentary forms, suggesting the existence of constellations that extend beyond a simple sum of composite parts and create their own meaning.

It strikes me that literature, as a never-ending process of telling stories about the world, has a greater capacity than anything else to show the world with a totality of the perspective of mutual influences and connections. Understood broadly, as broadly as possible, it is in its nature a network that connects and shows the enormity of the correspondence between all the participants of being. This is a very sophisticated and particular way of interpersonal communication, precise and at the same time total.

Writing this essay, I am constantly harking back to literature, now bringing up Kairos, now referring to Flammarion and the anonymous engraving that he dug up from somewhere so that it could serve as illustration for his book L’atmosphère. Météorologie populaire. I know that for many people literature is regarded as a trivial entertainment and comes down for them to just “something to read,” something without which it would be possible to live a happy and fulfilled life. Yet in its broadest sense, literature is above all an Open Sesame to the points of view of other people, visions of the world filtered through the inimitable mind of every individual. It cannot be compared with anything else. Literature, including the most ancient, oral, creates ideas and marks out perspectives that sink deeply into our minds and format them, whether we like it or not. It is literature that forms the matrix of the philosophers (what is Plato’s Symposium if not a work of good literature?), and it is from literature that philosophizing begins.

It would be difficult to create a vision of literature for our new times, especially since the well-informed tell us that the final reading generation has just matured. However, I would like for us to give ourselves the right to create new stories, new concepts, and new words. At the same time, I know that in the great, fluid, flickering universe that is the world, there is nothing new. This is a variable configuration that sets things up in a variable way, creates new associations, new concepts. The term “Anthropocene” is only thirty years old, but thanks to it we are able to understand what is happening around and to us. It’s made up of two well-known Greek words: ánthrōpos (man) and kainós (new) and indicates how great man’s influence is upon the functioning of natural processes on a global scale.

What would you say to ognosia?

Ognosia (French ognosie, Polish ognozja)—a narratively oriented, ultrasynthetic process that, reflecting objects, situations, and phenomena, tries to organize them into a higher interdependent meaning; cf. → plenitude. Colloquially: the ability to approach problems synthetically by looking for order both in narratives themselves and in details, small parts of the whole.

Ognosia focuses on extra-cause-and-effect and extralogical chains of events, preferring the so-called → welding, → bridges, → refrains, → synchronicities. A connection is often suggested between ognosia and → the Mandelbrot fractal set as well as → chaos theory. It is sometimes perceived as an alternative type of religious attitude, i.e. → altreligion, which seeks the so-called consolidating force not in some superbeing, but rather in inferior, “low” beings, the so-called → ontological odds and ends.

A handicap in terms of ognosia is manifested in the inability to perceive the world as an integral whole, that is, seeing everything in isolation; this creates a disturbance in the function → of insight into situations, synthesizing and associating apparently unrelated facts. In ognosia therapy frequently used are methods of treatment through the novel (short stories are also used on an outpatient basis).

Let us create a library of new terms. Let’s fill them with ex-centric contents, a table the center hasn’t heard of. We will after all lack the words, terms, expressions, phrases, and who knows if we might not lack whole styles and genres to describe what is to come. We will need new maps as well as the courage and humor of travelers who won’t hesitate to stick their heads outside the sphere of the world-up-to-this-point, beyond the horizon of existing dictionaries and encyclopedias. I’m curious what we will see there.

“Ognosia” © Olga Tokarczuk. By arrangement with the author. Translation © 2022 by Jennifer Croft. All rights reserved.