The dead don’t let us go, I say to my friend Sirius, putting my father’s letters in a drawer. It is the plight of Mezentius that I endure, attached to a dead man, hand in hand, mouth in mouth, in a sad embrace. The letters stopped arriving from the country of my childhood. The man who wrote them died a solitary death and was buried at the edge of a stream. But he is there, his skin touches my skin, my breath gives life to his lips. He is there, I say to Sirius, when I speak to you, when I eat, when I sleep, when I take a walk. It seems to me that I am dead, whereas my father, the dead man who refuses to leave me in peace, overflows with life. He possesses me, sucks my blood, gnaws my bones, feeds on my thoughts.1

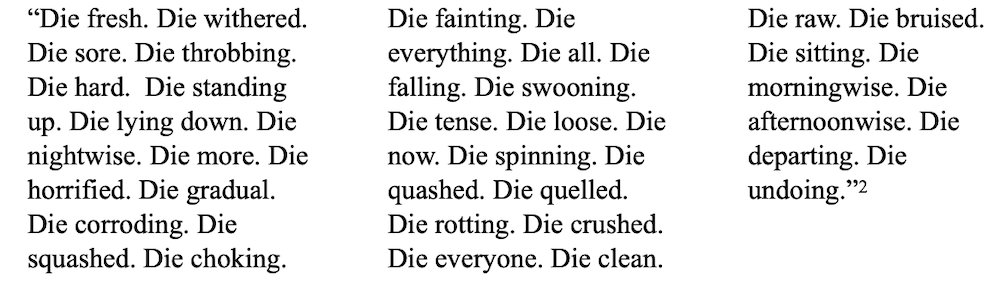

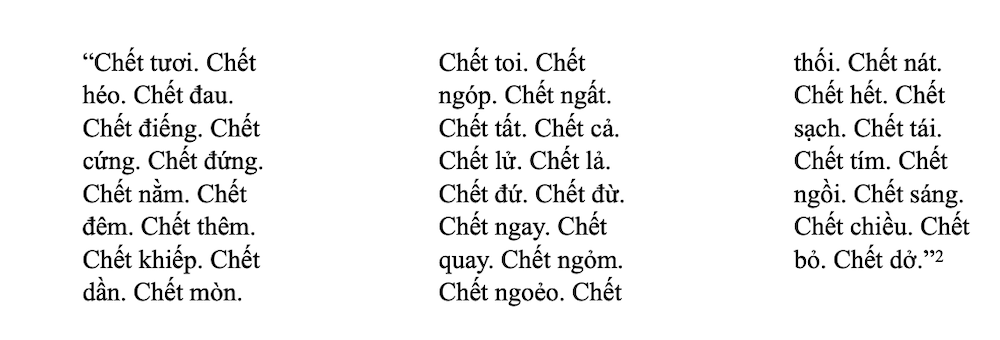

In the last letter, the dying man taught me a lesson of 36 deadly tricks. He called them the 36 documentations of secret agencies, 36 spells of horror, 36 faces of vanity, 36 tactics of being deadly, 36 stratagems of dying. All night long, I chant his weird song over and over like a crazy heart. Dripping drops of time, the tune flies far from the propaganda of a human life. When Sirius asks why I keep murmuring the lines, I say, It helps me learn my fathertongue, glide into my childhood siesta, melt into my red hot girdle of earth. The letters of the dead burn me, urge me to speak to them, speak them, have them speak me, even in my sleep. Every dream is a chamber where the language drills, like vital winds, hum me anew, blowing me closer to the waters where my father lies. Every night he still sleeptalks his fatal rhythm through my broken tongue.

All translations are by the poem’s assembler.

1. Linda Lê, Thư Chết, trans. Bùi Thu Thuỷ (Hà Nội: NXB Văn Học, Nhã Nam, 2013), 7. ↩

2. Trần Dần, Những Ngã Tư và Những Cột Đèn (Hà Nội: NXB Hội Nhà Văn, Nhã Nam, 2017), 259. ↩

“Chant Chữ Chết” © Nguyễn Hoàng Quyên. By arrangement with the author. English translation © 2020 by Nguyễn Hoàng Quyên. All rights reserved.

Read an interview with Nguyễn Hoàng Quyên about writing and translating “Learning Late Letters”