The Mario Vargas Llosa House Museum in Arequipa is in the high-altitude “White City” in southern Peru, known for its dazzling white stone and penetrating blue light. The Nobel laureate’s ghostly apparition as a speaking hologram welcomes visitors to the two-story house with wooden balconies where he was born on March 28, 1936. Memorabilia chart both his presidential bid and his life in letters—though, as Vargas Llosa once told me with a stiff laugh, his election defeat in 1990 confirmed that “I wasn’t a politician but a writer.”

His birthplace opened as a museum four years after his 2010 Nobel Prize. But like all museums, it has been shuttered during the pandemic. Despite being one of the first countries to lock down, on March 16, Peru has the second-worst coronavirus toll in South America after Brazil (and, as of July, the sixth-highest in the world). Its excess death rate (mortality above the usual average) has been one of the worst anywhere. In a country where seventy percent of workers labor precariously in the informal sector, without social safety nets, Peru’s second-largest city, Arequipa, and its capital, Lima, saw an exodus as tens of thousands trekked back to their home villages. Today Arequipa finds itself at the epicenter of Peru’s dire health crisis. Yet in normal times, the city’s renown rests on its UNESCO World Heritage Center and Andean-Pacific gastronomy.

The museum guides’ claim that the ground shook at the writer’s birth is not as implausible as it sounds. The White City sits at the foot of three snow-capped volcanoes: El Misti, Chachani, and Picchu Picchu. When the Spanish refounded the Incan city in 1540, along a corridor to the Pacific from silver mines that stretched to Bolivia, the vaulted ceilings of its colonial churches and mansions were to withstand frequent earthquakes. Volcanic ash turned to stone (sillar), rough to the touch, is the ubiquitous raw material for unique mestizo architecture that marries baroque with Inca iconography (sculpted suns, pumas, and corn on church facades), and for the immense seventeenth-century cathedral on the Plaza de Armas, where the would-be president held one of his first campaign rallies.

He spent barely a year in this Andean city, of which he wrote, “I remember nothing.” His mother took him to Bolivia when he was one, and thence to Piura and Lima on the Peruvian coast. His fiction ranges across Peru’s three climate zones: the Pacific coast, the Andean sierra (mountains), and the Amazon jungle. Yet Arequipa’s conservatism, as a colonial city built on social as well as geological fault lines, marked his life and foreshadowed his fiction. And beyond the oeuvre of its most famous writer, these social, cultural, and geographical fissures run deep throughout the literature of Peru.

“Intermarriage and miscegenation were rife, but so too were growing anxieties about racial mixing.”

As Vargas Llosa wrote in his 1993 autobiography, A Fish in the Water (tr. Helen Lane), his parents were wed in this, his maternal grandparents’ house, on Bulevar Parra, south of the historic center. But his father, Ernesto Vargas, walked out before he was born. The shame of Dora Llosa’s abandonment with a “fatherless child,” in a family whose aristocratic airs belied modest means, drove them out of Arequipa. He attributes this marital “disaster” to his father’s crippling sense of social inferiority. An apprentice shoemaker turned radio operator, “his life with my mother was ruined by the sensation, which never left him, that she came from a world of names that meant something—those Arequipa families that boasted of their Spanish forebears, of their good manners, of the purity of the Spanish they spoke.” Ernesto’s bitterness was compounded by the perverse resolve of the writer’s paternal grandfather to “live with an Indian woman who braided her hair and wore wide skirts, in a little village in the central Andes”—which “filled my progenitor with shame.”

Vargas Llosa became a close observer of Peru’s stratified and regionally split society, its seemingly parallel yet intimately colliding worlds. His memoir excoriates the “national disease” afflicting “particoloured Peruvian society” and “poisoning the lives of Peruvians in the form of resentment and social complexes” that are “taken in with one’s mother’s milk.” His father had “white skin [and] light blue eyes,” but had come down in the world to a point where “Peruvians who believe that they are blancos (whites) begin to feel that they are cholos, that is to say, mestizos, half-breeds of mixed Spanish and Indian blood, that is to say poor and despised . . . one is always blanco or cholo in relation to someone else.”

Politics of Rust – Product III (Indian Red) from Sandra Gamarra’s 2018 painting series, Políticas del óxido, inspired by eighteenth-century “casta paintings” that depict the offspring of racial mixing. This one is headed: “Spaniard. Highland Indian. Or Coffeed. Product Mestiso.” Red iron oxide on canvas, 130 x 130 cm. (Courtesy of the artist)

This insight propels the furious satire of Vargas Llosa’s first novel, The Time of the Hero (1962; tr. Lysander Kemp)—a founding classic of the so-called Latin American Boom. His father (who reappeared in his mother’s life when he was ten) was so appalled by his son’s writing poetry—and fearful that it signaled homosexuality—that he sent him to the Leoncio Prado military academy in Lima. This was a “window on the real country, Peruvian society in miniature,” Vargas Llosa told me in 2002 for a Guardian profile. “Because of grants you had all social classes and races—white, black, Indians, mestizos, mulattos, from the upper class to the very poor. It was an explosive climate where everybody was prejudiced, with tremendous tension and violence. I suffered because I was spoiled, but it was an extraordinary lesson.” With its brutal bullying and hazing, the cadet school became the novel’s microcosm of Peru under General Manuel Odría’s 1948–56 military rule. The coup that brought him to power had opposed the radical Apra party (Popular Revolutionary Alliance of America) that grew from a demand for Indian rights.

“Peru was the capital of the Spanish empire in South America. That was the beginning of the relationship between races,” Santiago Roncagliolo, a leading novelist of the post-“Boom” generation, told me over coffee during the second edition of Hay Arequipa (a literary festival founded in 2017 following Hay Cartagena in Colombia). After Pizarro’s arrival in 1531, Spain ruled swaths of the continent through Lima’s opulent court under the Peruvian viceroyalty of 1542–1821. “One civilization defeated another,” Roncagliolo said. “That’s very strong in the subconscious of Peruvian society.” Yet the cultural conquest was less absolute than elsewhere on the continent: Peru has forty-eight surviving indigenous languages, including Quechua, that of the vast Inca empire—the mother tongue of fourteen percent of Peru’s current population of almost thirty-three million.

“There’s a moral meaning in memory—and literature is in charge of making us remember.”

As the country prepares to mark its bicentenary of independence next year, “the colonial system is still alive in Peru,” the Madrid-based artist Sandra Gamarra told me. “The idea of race, of different levels of humanity, is in our culture.” The Spanish made marriage alliances with vanquished Inca nobility—witness an eighteenth-century oil painting in the Jesuit church in Arequipa of the 1572 wedding of a conquistador and an Inca princess (a version of this painting, as I wrote in the New York Times, was feted last year at the Prado in Madrid). Intermarriage and miscegenation were rife, but so too were growing anxieties about racial mixing. Gamarra’s recent series of sepia-like family portraits play on “casta paintings” in vogue in the eighteenth century, depicting mixed-race couples whose offspring are labeled with almost zoological precision. As peninsulares from Iberia vied with American-born criollos, their “impure” progeny were classified by caste: the child of a Spaniard and an Amerindian (mestizo or cholo); Spaniard and mestizo (castizo); mestizo and Amerindian (lobo). As enslaved Africans replaced Amerindian labor ravaged by European diseases such as smallpox and influenza, more terms were deployed for Spaniard and African (mulato) or African and Amerindian (zambo). Yet in this bizarre racial pecking order, education, wealth, and Catholicism might offer a ladder to social mobility. This was the pathological history underlying Ernesto Vargas’s anxieties.

Teresa Ruiz Rosas, a writer and translator from Arequipa whose parents ran a bookstore in the city, told me its reputation as La Ciudad Blanca was not just for its volcanic stone. Migration from the Andean highlands has changed its demography. “Arequipa and Lima are now so mixed. But in my youth, it was called a white city because it was dominated by people of European origin”—those, like the Llosas, who vaunted Spanish ancestors.

Beside the hotel bar where we spoke, Arequipa’s Convent of Santa Catalina—founded in 1575 and the biggest in South America—is as telling a microcosm as Vargas Llosa’s cadet school. Ruiz Rosas remembers the convent’s opening to a curious public in 1970. Inside, the street names and Mudéjar style bow to Moorish Andalusia with fountains, orange trees, and houses painted terra-cotta and brilliant blue. But its past is less picturesque. Wealthy families from surrounding haciendas paid lavish dowries in silver for a daughter to take the vows, a privilege reserved for descendants of Spaniards—though not always relished by the girls as young as twelve who were immured (one runaway set fire to the convent). Wealth oozes from an ex-dormitory filled with Cusco-school oil paintings (the extraordinary mestizo proselytizing art that flourished in the former Inca capital during the viceroyalty). Poor mestizas born out of wedlock joined the convent hierarchy beneath the “pure.” In its heyday, two hundred cloistered nuns—some in luxurious private suites with libraries and musical instruments—were outnumbered by indigenous servant women who ground corn flour, did the laundry, and emptied their chamber pots.

The Santa Catalina walled convent in Arequipa, where only descendants of Spaniards could take the vows. Photo copyright © Maya Jaggi

“Behind Toledo Street” (tr. Psiche Hughes), Ruiz Rosas’s short story set in the convent—which won the 1999 Juan Rulfo Prize—grew from her shock at its claustrophobic penitence cells. A “self-made tourist guide” with “delicate mestizo features” and “flowing blue-black hair” relates how she tricked the Cuban gigolo who left her pregnant by locking him into a cupboard-like cell. She is from a “rugged land” of people “born to work like mules. And rather revengeful.” She knows the porous sillar walls will “guard the smell of his putrefying corpse like a secret.” Ruiz Rosas said, “I wanted the perfect crime without blood. Ever since the conquest, it was normal that indigenous women could be taken and left, no matter what happens to the ‘bastard’ children.” Rather than vengeance, the narrator sees her “obsessive need to punish” as a principled response to a legacy of injustice, exploitation, and denial.

That enduring legacy has divided the country’s fiction. For Roncagliolo, “there are two main streams in Peruvian literature all through the last century.” One, led by José María Arguedas, “documented the problems of Indian people, and thought literature was a social weapon.” The other he sees as led by Vargas Llosa, who “could also write about social justice, but was against social revolutions, and thought the novel was more the crafting of beauty, of a universe.” Writers who belong to the latter stream, developing an individual style, are “usually middle- or upper-class writers from the capital, connected with Europe.” The polished selected stories of Julio Ramón Ribeyro, who lived in Paris and died in 1994, fall into this second stream—though the title of a collection published in New York Review Books Classics as The Word of the Speechless (2019, tr. Katherine Silver) underlines his deep concern, too, for “the marginalized, the forgotten, those . . . without voice.” Roncagliolo (b. 1975), of a new generation, sought his own way to “write both about social justice and also with passion and craft; I don’t want to get trapped in either of those groups.”

Sensing the revolutionary potential of novels, the Inquisition had taken the precaution of prohibiting the entire genre throughout Spanish America (claiming it was bad for Amerindians’ spiritual health), along with all works of the imagination about native peoples. Under the free republic, exotic “Indianist” novels, such as Clorinda Matto de Turner’s Birds Without a Nest (1889; tr. J. G. H., emended by Naomi Lindstrom)— sometimes characterized as a Peruvian Uncle Tom’s Cabin—gave way to social realist Indigenista writers. Some were published in José Carlos Mariátegui’s avant-garde magazine Amauta (Quechua for “wise man”) in Lima in 1926–1930—the subject of an excellent touring exhibition at the Blanton Museum of Art in Texas through August 30.

“Some fiction did more to confirm a gulf of incomprehension than to bridge it.”

Indigenista writer Ciro Alegría, in his panoramic novel Broad and Alien Is the World (1941; tr. Harriet de Onís), wrote as someone who had spent time on his grandfather’s hacienda, and was sympathetic to noble Indian peons brutalized by feudal landowners. But Arguedas’s novels, including Yawar fiesta (1941) and Deep Rivers (1958)—both translated by Frances H. Barraclough—were a revolution in perspective. The son of a provincial judge in the highlands, rejected by his stepmother after his mother died young, Arguedas was cared for by Quechua speakers, and later anthologized Quechua songs as a trained anthropologist. Driven to protest, while remolding Spanish to express the Quechua tongue and cosmogony, “I tried to convert into written language what I was as an individual: a link . . . between the great imprisoned nation and the generous, human section of the oppressors,” he wrote in 1968. For Roncagliolo, “Arguedas is an amazing writer who lived in the sierra, who had a point of view no other writer had.” But the irreconcilability of his two worlds (and a spat with the Argentinian “Boom” author Julio Cortázar) drove him to suicide in 1969.

The chasm between coastal city and sierra widened during the armed conflict that erupted forty years ago, when civilians were caught between brutal guerrilla groups and state counterinsurgency forces waging their own “dirty war.” The Maoist guerrillas of Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path), led by the Arequipa-born philosophy professor Abimael Guzmán (jailed in 1992, and still in prison aged eighty-five), initially gained a foothold by sending teachers to desperately deprived rural areas. More than seventy thousand people were killed over two decades, driving an exodus from the Andean provinces that bore the brunt of the violence. Ruiz Rosas (who remembers Guzmán frequenting her parents’ bookstore) said the capital seemed oblivious to the unfolding terror until “bombs began to go off in Lima too, and people finally paid attention.”

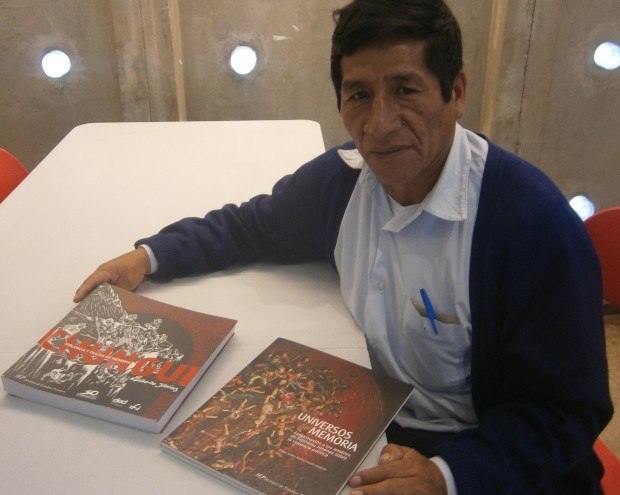

Andean artist Edilberto Jiménez, pictured in Lima with books of his work. An early chronicler of the “dirty war,” he based his art on Quechua testimony he collected of atrocities by both Shining Path guerrillas and state forces: “People in Lima couldn’t believe this happened in Peru.” Photo copyright © Maya Jaggi

The first chroniclers of this war were Andean artists. Edilberto Jiménez, a bilingual sociologist and retablista, drew on Quechua testimony he collected of atrocities by both guerrillas and state forces for his drawings and retablos (boxed tableaux of wooden figures, traditionally of Catholic scenes). As he told me in Lima in 2018, although many of his works were “destroyed by the army and police,” those that survived shocked recent audiences in the capital: “People couldn’t believe this happened in Peru.”

Short stories by Andean writers followed from the mid-1980s. But the novelist Karina Pacheco, cofounder of an independent publishing house in Cusco, Ceques Editores, told me media attention was scant because of a centralist focus on Lima writers. Early novels to emerge from the conflict included Julio Ortega’s Ayacucho, Goodbye (1986, tr. Edith Grossman) and La violencia del tiempo (The Violence of Time, 1991) by Miguel Gutiérrez, who died in 2016 and has been hailed as an heir to Arguedas. Yet some fiction did more to confirm a gulf of incomprehension than to bridge it. For Pacheco, Vargas Llosa’s novel Death in the Andes (1993; tr. Edith Grossman) “reflects the vision of part of Peru toward the other Peru.” That whodunit followed the real-life disappearance of eight journalists in the early 1980s, which Vargas Llosa was involved in investigating. In “The Story of a Massacre,” a 1983 essay in Making Waves (1996, tr. John King), he wrote that the “Indians in sandals and colored ponchos that they glimpsed herding flocks of llamas were as exotic” to the Lima journalists as to any tourist. But that essay’s nuances seem lost in the novel’s atmosphere of menace, where pre-Columbian rites symbolize Shining Path’s orgy of blood, and high-Andean culture becomes conflated with primitive barbarism.

“For my generation, it’s very difficult to see who’s good and who’s bad.”

In 2003, when Peru’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission concluded that state forces shared the blame for atrocities against civilians over two decades, its explosive report deeply unsettled assumptions about who the civilized were, and who the barbarians. Alonso Cueto’s The Blue Hour (2005; tr. Frank Wynne), which won the Premio Herralde de Novela, is among the novels that reflect this shifting moral ground. A Lima lawyer searches for a woman from Ayacucho whom his late father (an army commander) had imprisoned, but who had escaped at the “blue hour of first light”— and whose son the lawyer believes to be his half-brother. The novel led many Peruvian readers not only deep into the Andes (“all [Limeños] know about this place is that they think the handicrafts are pretty”) but into Lima’s own barriadas (shanty towns). While the lawyer’s wife assumes him to be having an affair with “some chola,” he learns that his father’s lover, whose relatives were all killed by Shining Path, had been held in a “barracks policed by torturers.” In such a “divided world,” the “line between them and us is razor thin.” Only the woman’s love and forgiveness, while redeeming the father, stretch credulity.

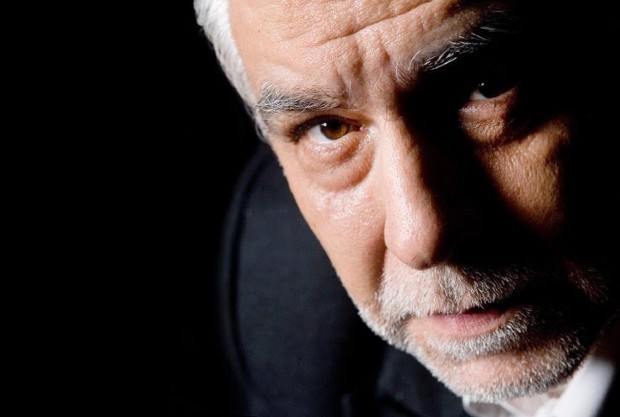

“There’s a moral meaning in memory—and literature is in charge of making us remember,” Cueto told me one morning in Arequipa. His narrator’s father is an “ambiguous figure he had thought was rude and ruthless, but who had been kind.” In the son’s “search for the past to redeem his father’s faults, he understands his father, his family, his country, and himself.” Peru, for Cueto, is a “country full of languages and cultures, with cities where people gather from different areas and try to live with each other. Conflict, discrimination, and violence are very frequent. It’s much improved, more integrated, than forty years ago, when Shining Path started—but it’s not an integrated country.”

Lima novelist Alonso Cueto: “Peru is much improved, more integrated, than forty years ago, when Shining Path started—but it’s not an integrated country.” Photo copyright © Daniel Mordzinski

More ambiguous and less redemptive than The Blue Hour is Roncagliolo’s Red April (2006; tr. Edith Grossman), which won the Alfaguara Prize and the 2011 Independent Foreign Fiction Prize. During Holy Week of 2000 in Ayacucho, as burnt corpses turn up with limbs torn off, a Lima prosecutor investigates a suspected serial killer. The child of a mother from Cusco and a white soldier from the capital, he struggles with his own prejudices against the “unfathomable” locals, whose ancient beliefs are held in almost superstitious dread. As one character tells him with dramatic irony: “You don’t know these half-breeds . . . They’re violent people.” The novel hints at how insidiously the investigator’s own prejudices become part of the problem. For others, it was “them or us.” For him, “We waged a just war . . . But sometimes I have difficulty distinguishing between us and the enemy.”

The son of an exiled politician, Roncagliolo’s understanding of Peru’s bitterly riven society stemmed not only from his childhood during the armed conflict (“This was my war; I grew up in it”), but also his work with the Human Rights Commission in the 1990s, when he witnessed the “scars of war.” Peru, he learned, was a “country of people who hated each other. Everyone supported killing the other side”: people from the mountains versus the cities; the poor versus the rich. “There was no middle point, no dialogue, and no contact. After fifteen years of killings and kidnappings, and not being able to leave your city because the highways were dangerous, that makes people racist because they don’t know each other.” Red April was sparked by the Atocha bombing of 2004 in Madrid (where he was living) and the response to terrorism: “I’d seen all these things before, and they were wrong.” Although, like Death in the Andes, his novel uses the crime thriller genre, “it was a different time,” he told me. “In 1993 we were aware of the cruelty of terrorism. But ten years later, there was also consciousness of the cruelty of the state. For my generation, it’s very difficult to see who’s good and who’s bad.”

The Blue Hour and Red April, anointed by international prizes, raised awareness of the Andean holocaust in the rest of the country, according to Pacheco. “A lot of readers in Peru approach political violence through fiction and films to get closer to a broader spectrum of people—and stories affect people more deeply” than nonfiction. To her own novels, which include No olvides nuestros nombres (2008; Do Not Forget Our Names), have been added other women’s voices, such as that of Claudia Salazar Jiménez, whose first novel, Blood of the Dawn (2013; tr. Elizabeth Bryer), traces the impact of sexual violence on three women during the conflict—and won Las Américas Prize for Narrative in 2014. (Like Daniel Alarcón, who writes mainly in English, she lives in the US.)

“The curfews imposed during the pandemic have stirred memories of the war years.”

The past decade has seen an outpouring of testimonial literature from different sides of the conflict. “New voices have arisen that would have been impossible twenty years ago,” Roncagliolo said, “because now you can talk about the past from many points of view.” But the “real change is readers. They’re not just middle-class white people from the city. Everybody’s gone to school.”

Lurgio Gavilán Sánchez’s When Rains Become Floods: A Child Soldier’s Story (2012; tr. Margaret Randall) is the testimony of a Quechua-speaking boy who followed his brother into Shining Path, was then recruited into the army, and escaped the war to become a Franciscan priest and anthropologist. Also in English translation is Renato Cisneros’s novel The Distance Between Us (2015; tr. Fionn Petch), a son’s fictionalized search through family history for his late father, a military leader during the conflict.

José Carlos Agüero’s Los rendidos: Sobre el don de perdonar (The Surrendered: On the Gift of Forgiveness; 2015) are the reflections of a poet and historian whose parents were Senderistas. Marco Avilés, whose family migrated to Lima from the Andean city of Abancay, confronts attitudes that underpinned—and outlived—the years of violence, in books such as De dónde venimos los cholos (Where We Cholos Come From, 2016). As Avilés has written of joining a Lima newspaper: “I’d crossed the border from one country into another. Both were called Peru, but they had nothing to do with one another.”

Cusco novelist Karina Pacheco: “A lot of readers in Peru approach political violence through fiction and films—to get closer to a broader spectrum of people.” Photo copyright © Daniel Mordzinski

Literature in (and translated from) indigenous languages may be vital in bridging this gulf. More than seventy-five percent of those who died in the war were mother-tongue speakers of Quechua or other native languages. Pacheco, who doubts “we’ve made a really deep reflection on this as a society,” said the “Spanish language still has all the opportunities in Peru.” The country officially became bilingual in 1975, when Quechua was recognized. But the past decade has seen a marked shift. Hugo Coya, a writer and filmmaker, launched the first indigenous-language programs on national radio and television in 2016, when he was director of Peru’s TV and Radio Institute, beginning with Nuqanchik (Quechua for All of Us). Speakers of Quechua, he told me from Lima, still suffer discrimination and “linguistic shame. Because it’s been synonymous with poverty and backwardness, it may be spoken almost clandestinely inside people’s homes. But it’s not true it’s only in the sierra. Quechua is spoken all over the country.” Of the million inhabitants of San Juan de Lurigancho, Lima’s most populous district, sixty percent are Quechua speakers. Audiences for recent, internationally prizewinning films in Quechua and Aymara “were spectacular. Spanish-speakers have discovered how rich these languages are. It’s important to preserve and revitalize them aggressively.”

Felix Lossio Chávez, a sociologist and academic who was, until May, general director of cultural and creative industries at Peru’s Ministry of Culture (created in 2010), is mindful that “more than twenty percent of Peruvians don’t have Spanish as their main language.” He pointed to a growing interest in bilingual and trilingual books—including children’s literature—which have government support. The National Literature Prize created an indigenous-language category in 2018 to cover a tiny but growing number of books. That year, thirty-eight new publications in those languages were registered at Peru’s national library. Within a year, the figure had risen to sixty-three. Such publishing is now part of a new official reading strategy geared to “biblio-diversity.” But this year’s Lima Independent Book Fair, which gives vital support to regional publishers, was canceled owing to the coronavirus.

The curfews imposed during the pandemic have stirred memories of the war years. Roncagliolo had thought Peru a “more civilized place now than it was then, trying to build a state for everybody.” But watching events from lockdown in Barcelona, he felt the virus had accentuated “all Peru’s unsolved problems. I’ve seen really cruel scenes these last days—people saying, ‘let others die, not me’—that reminded me of the bad old times.” For Pacheco, the truth commission and the writing that flowed from it “helped to see that racism, inequality, and exclusion were the main causes of the big tragedies we’ve lived—the emergence of Shining Path and the devastating repression by army forces.” But she puts a failure to stem these inequalities down to “our pandemic racism.”

Lóssio is more optimistic that, while more needs to be done to “level the floor—the access to cultural infrastructure is extremely unequal—we’re more open to reading different points of view.” From lockdown in Lima, he told me: “Through books and films and art, we’re closer to understanding the complexity of what happened in the political violence and reconciling the distance we had.”

As coronavirus amplifies the country’s deep inequalities, and Peru faces its greatest challenge in generations, that understanding will be crucial.

© 2020 by Maya Jaggi. All rights reserved.

Further Reading on WWB:

Geography of the Peruvian Imagination

History of a Conversion: A Political Profile of Mario Vargas Llosa

The Ingenious Gentleman of the Andes—On Translating Cervantes’s Classic into Quechua