Almost every time a literary publication in the Western Hemisphere commissions a list of the best novels from India, they turn out to be a compilation of books written in the English language. For reasons of both colonial history—most of India was under the rule of the British Empire, first through the East India Company and then directly for 190 years, from 1757 to 1947—and of a continuous wave of fiction from Indian writers in English since Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children (1981), both list-makers and editors seem to forget that India is in fact a country with 20,000 tongues, which are variations of over 120 distinct languages.

The country has, in fact, twenty-two official languages, and of these, English is the most recent arrival. All the other languages—which include but are not limited to a range from Malayalam, Tamil, Kannada, and Telugu in the south to Urdu, Kashmiri, Punjabi, and Hindi in the north, from Marathi, Konkani, and Gujarati in the west to Bengali, Odia, and Assamese in the east—are of older vintage. What’s more, the literatures in each of these languages goes back much further than English literature in what is known today as the country of India.

Where, then, should a world reader look for books from India? Those written in English are an important, but by no means the only, port of call. Of course, they have a disproportionate share of voice because they are published with greater frequency in the Anglophone world, and because English is the professional, social, and now even personal language of the educated elite of India. However, there exist more than a dozen different literatures in the country, each in its own language, that can provide a far better sense of the almost bewildering diversity of voices, themes, forms, settings, characters, and historicities of literary India.

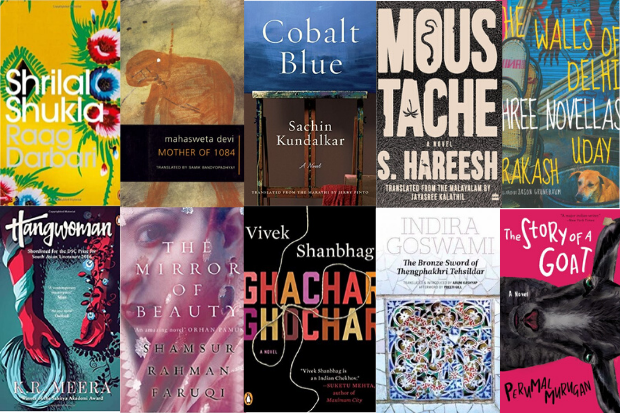

As a beginning, here is a list of ten novels from non-English languages, translated into English. The objective is not to create a best-of list, but simply to provide a flavor.

1. Moustache by S. Hareesh, translated from Malayalam by Jayasree Kalathil | HarperCollins India

S. Hareesh’s magical Malayalam novel, lyrically translated by Jayasree Kalathil, cares neither for a single story nor for a small cast of characters. Vavachan, a member of a so-called lower caste in the southern state of Kerala, puts on a moustache for the role of a policeman in a play—after which the moustache acquires mythical proportions through the imagination of the oppressed. This is a novel that is not so much a narrative as a collective journey.

2. Mother of 1084 by Mahasweta Devi, translated from Bengali by Samik Bandyopadhyay | Seagull Books

Activist-writer Mahasweta Devi’s clear-eyed novel, translated crisply by Samik Bandyopadhyay, chronicles the violent, extreme-left political movement that overtook Calcutta in the 1960s and 1970s through the eyes of a mother whose son, Brati, a part of this uprising, is killed in a police encounter. After his death, his identity is reduced to “Corpse Number 1084” in the morgue. And his mother, Sujata, through whose grief and pride, love and resilience, this novel unfolds, becomes the “mother of 1084.” In Sujata’s conflicts Mahasweta Devi merges both the external political turmoil—pitting class against class, society against the establishment, firebrands against the authorities—and the internal, familial one of the mother/wife/daughter figure who is seeking freedom and equality on behalf of herself as well as womenkind in general.

3. Cobalt Blue by Sachin Kundalkar, translated from Marathi by Jerry Pinto | The New Press

Sachin Kundalkar’s first novel, written in Marathi when he was just twenty-two, is a tender exploration of a love triangle bursting with the fullness of the multiple relationships that inform the lives of its protagonists. A young man moves in as a paying guest to a house occupied by a brother and sister, both of whom, unknown to him perhaps, fall in love with him. Jerry Pinto’s delicate translation privileges emotional fidelity over semantic proximity, which gives the novel both an intensity and a lightness.

4. Raag Darbari by Shrilal Shukla, translated from Hindi by Gillian Wright | Penguin

The Hindi writer Shrilal Shukla turns a mercilessly satirical gaze on the corruption and complicity that have long marked the governance systems of rural India in particular. An idealistic college student travels to his uncle’s village after graduation to tend to his failing health, and comes across an astonishing nexus between rich individuals and every arm of the administration to create a well-oiled machine that serves nobody but those in power. Translator Gillian Wright captures the nuances of Shukla’s acerbic pen, fortunate in that the English language lends itself to this form quite effectively. This novel can well lay a claim to being one among many seminal stories from India.

5. Hangwoman by K. R. Meera, translated from Malayalam by J. Devika | Penguin

In K. R. Meera’s novel, set—unexpectedly or otherwise for a writer from Kerala—in Bengal, twenty-two-year-old Chetna Grddha Mullick is thrown into a situation she might not have anticipated. Her father, Phanibhushan Grddha Mullick, the last male in a family with a lineage going back thousands of years, whose traditional occupation is hanging condemned criminals, is now too old to do the job. And there is a new prisoner waiting to be hanged. Choosing not to disrupt the family line, Chetna decides she will do the job. Or does she? Is it possible that she has been manipulated by the sensationalist media? This is an urgent, vibrant, rich, and relentless novel—whose translation by J. Devika is uncompromising on all parameters—that deftly constructs the messily complex theater in which the drama, and it is nothing less than a drama, plays out.

6. The Bronze Sword of Thengphakhri Tehsildar by Indira Goswami, translated from Assamese by Aruni Kashyap | Zubaan

The last work of fiction by the Assamese writer Indira Goswami, The Bronze Sword of Thengphakhri Tehsildar, is a remarkable work that uses folklore, songs, and stories passed orally down generations to construct a novel. Its subject is the first woman revenue collector of the state of Assam, back in the 1850s, who traveled on horseback to collect taxes. While initially employed by India’s colonial British rulers, Thengphakhri’s switch to become an insurgent—and a freedom fighter—is one of the key narratives of this novel, which also offers context for some of the violent political movements in the state more than a century later. Coming as it does from a part of India that has suffered greatly from not being considered an integral part of the country by people in other states, this novel, translated movingly by Aruni Kashyap, is especially important in staking a claim amongst the literatures of India.

7. The Mirror of Beauty by Shamsur Rahman Faruqi, translated from Urdu by the author | Penguin

A vast saga of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century India, when the end of the centuries-old Mughal Empire and the establishment of British colonial power led to collisions of social culture and individual behavior, The Mirror of Beauty charts a complex trajectory through the life of the stunningly beautiful Wazir Khanam. An entire world comes to life over the thousand-plus pages of a novel that could only have been written in Urdu, for one could argue that no other language can fuse the form and content of sensual opulence with philosophical reflections. The author’s self-translation bends English to the will of Urdu to recreate that lushness.

8. Ghachar Ghochar by Vivek Shanbhag, translated from Kannada by Srinath Perur | Penguin

The big bang economic liberalization of India in 1991 was the equivalent of a switch thrown suddenly to open up the middle class to the prospect of a sudden improvement in income, wealth, and property ownership. Thousands of families in dozens of cities across the country found themselves climbing out of stagnant earnings and low-intensity consumption to join the ranks of carefree consumers. Something, however, got left behind in the mad rush to acquire homes, cars, gadgets, and lifestyles—honesty and ethics. Ghachar Ghochar is the story of a Bangalore family caught in this transition from a life of strained means to one of sudden affluence. Shanbhag skilfully creates a moral knot in the lives of the members of this family as they struggle to deal with their newfound prosperity, which threaten the values they had lived with earlier. The title of the novel, a phrase coined by one of the characters, signifies an impossibly snarled drawstring, which effortlessly represents the state of affairs for the main characters. This slim novel, translated with great creative integrity by Srinath Perur, leaves you with the aftertaste of having read a monumental work of fiction.

9. The Story of a Goat by Perumal Murugan, translated from Tamil by N. Kalyan Raman | Grove Press, Black Cat

“I am fearful of writing about humans; even more fearful of writing about gods,” writes Murugan in the preface to his first novel after withdrawing temporarily from writing following open threats of violence against him and his family in response to his best-known novel, One Part Woman. Writing in the form of a fable this time, Murugan asks what happens to the nonconformist in a rigid, intolerant society, but locates his narrative in the world of goats instead of humans. Far from being strident, however, this is a gentle novel that brings an unexpectedly comforting touch.

10. The Walls of Delhi: Three Stories by Uday Prakash, translated from Hindi by Jason Grunebaum | Seven Stories Press

Delhi is not only the capital city of India but also, arguably, the space that best represents the bewildering confusion of a country at cross-purposes with its past and future, where thousands of different groups of people try every moment to negotiate survival, well-being, success, identity, relationships, and, most of all, shortcuts to wealth. Naturally, one individual’s accomplishment is often another’s ruination. The Walls of Delhi, a collection of three stories by Uday Prakash, captures this gestalt with scenarios that would be completely unreal if they weren’t so plausible in the maelstrom that is modern urban India. In one story, a sweeper finds a stash of money hidden away by someone trying to evade taxes, using it to take his distinctly underage lover to Agra for a glimpse of the fabled Taj Mahal. In a second story, a Dalit—a member of the oppressed “castes” in India’s repulsive but extant “caste system” of discrimination on the basis of a person’s lineage—finds his identity stolen by an “upper caste” man who is trying to cash in on the benefits of affirmative action. And in the third, a family tries to cure a baby of its “illness” of extreme intelligence, represented by an ever-growing head. The fiction here is a fascinating projection of reality.

Postscript: A Ballad of Remittent Fever by Ashoke Mukhopadhyay, translated from Bengali by Arunava Sinha | Aleph Book Company

One of my favorite books, and one that I recently had the joy of translating, A Ballad of Remittent Fever is told through the stories of three generations of doctors who face a sweeping range of diseases, epidemics, and pandemics, as well as the constant battle between scientific rationalism and dogmatic tradition playing out in the lives and deaths of patients. The doctors themselves are driven by their mission as well as by personal demons, but they always affirm life. The novel provides a journey through public health and private lives over the course of seventy years in Calcutta and Bengal, as it tells the stories of one doctor’s obsession with curing those whom others have given up on, another’s for his cousin, and that of a third for finding the identity of a mysterious man in the hills.

Copyright © 2022 by Arunava Sinha.

Disclosure: Words Without Borders is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and will earn a commission if you use the links above to make a purchase.