When we first proposed a feature on Mexico in April 2014, our idea was to shift thematically away from the Words Without Borders Mexican Drug War Issue in 2012. Tapping into the celebratory mood of the 2015 cultural partnership between Mexico and the UK, and the showcasing of Mexico as the Market Focus at the 2015 London Book Fair, we simply wanted to share some of the best contemporary stories and poems we could find.

We agreed our feature need not be an obvious sequel to the vital issue of this magazine edited by Carmen Boullosa, which aimed to “document the [drug war] crisis and demand the world’s attention.” Rather, it presents a kind of step back from, or suspension of, the drug war topic—hence our title, “Mexico Interrupted.” If fiction—especially translated fiction—increases readers’ awareness of shared human experience across nationalities, then our intention with this feature was to share other, non-newsworthy Mexican realities. Our selection mirrors some of those realities, with all the heartache, fear of old age, fear for one’s children, thwarted ambitions, writer’s blocks, and professional snipes and gripes they might entail.

There’s an obvious irony in trying to promote diverse Mexican literatures by means of a handful of texts. Our method, though, was simply to read as many writers as we could, of all ages and publication histories. (For a more comprehensive though by no means exhaustive taste of contemporary Mexican fiction and nonfiction, look out for Pushkin Press’s anthology of the collaborative project México20, published in April.) A few months later we came together having each picked out a number of stories that we could really say had left a mark on us. We thought a theme would emerge. It didn’t; instead, three stories and a poem did. In this respect, “Mexico Interrupted” also appealed to us as a sort of anti-theme, since our varied selection confirmed the futility of us trying to neatly label writers simply because they all hail from the same country.

Of course, we didn’t have a crystal ball, and couldn’t have imagined the scene at the Raúl Isidro Burgos Rural Teachers’ College in Ayotzinapa, in southern Mexico on September 26, nor how many Mexicans’ worst fears about the links between their government and narco-related crime would subsequently be confirmed. The so-called drug war has gone from grim to grimmer: Rafael Lemus’s insight in this magazine in 2012 that “the federal government does not have a strategy—a clear, robust, sustainable strategy—for fighting organized crime” is a sad understatement in the wake of revelations about the Mexican federal government’s collusion with those criminals in kidnappings and killings.

Nor could we have foreseen that Mexico would mobilize itself to the extent that it has since September. Writing in the New Yorker at the end of last year, Francisco Goldman proposed: “The popular hashtag slogan ‘We are all Ayotzinapa’ really does have to mean all of us, both in Mexico and outside it. The civic movement that has begun must be sustained.” To a great extent, it has been. On November 20, tens of thousands of people protested in Mexico City, and throughout the country, demanding information about the whereabouts of the missing students, and political resignations: in short, the end to a cycle of impunity. Today, Horizontal.mx magazine, founded in late 2014, also runs community-style workshops and talks, providing fertile ground to reimagine Mexican politics and society “after Ayotzinapa.”

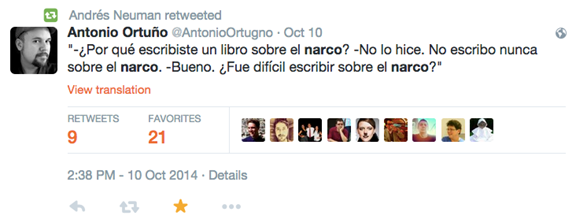

If anything, Ayotzinapa reinforced our hope that this feature would interrupt the burgeoning stereotype that Mexican literature = narcoliterature. The “interruption” does not call for an end to any kind of literature; on the contrary, it is a way to suggest that the term “Mexican literature” only makes sense if it refers to many literatures. A tweet by Antonio Ortuño in October 2014 reinforced what other Mexican authors, including Juan Pablo Villalobos, have written about the flipside of a narcoliterature “boom”:

(“Why did you write a book about narcos?” “I didn’t. I never write about narcos.” “Right. Was it hard writing about narcos?”)

This interruption, then, is also a continuation: a continued effort to focus on Mexico and draw attention to a country that asks to be discussed expansively. In a speech given at the London Book Fair in April 2014, the writer Valeria Luiselli suggested that “the more Mexican literature is read, the less clear it will be to everyone what Mexican literature really is. This is a good thing; a ‘happy ending’ of sorts, as anything that can be pigeonholed is not worth understanding.” Post-Ayotzinapa, arguably it goes deeper than that: any national literature that is pigeonholed by politics threatens to misrepresent that nation altogether.

Yuri Herrera and Luis Felipe Fabre both appeared in the 2012 Mexican Drug War issue. We’re delighted to show them in other guises in the run-up to their English language publications this year. Fabre’s poem is a tongue-in-cheek poetic diatribe against an internationally recognizable academic type (you could substitute his Sor Juana for Proust, Beckett, Dante to hilarious effect), while Herrera throws us into a familiar wedding reception scene, and into the caustic mind of an aging bachelor who must confront an old romantic rival—he’s an irresistibly despicable narrator. Laia Jufresa’s background as an illustrator feeds into her story about Cornerism. What is Cornerism? You’ll have to read it to find out; suffice to say, while Jufresa does not portray contemporary social reality, she does paint a lucid and haunting picture of a possible future. Agustín Goenaga, also appearing in Words without Borders for the first time, presents us with a highly personal, Raymond Carver-inflected metafiction.

If you’re going to try to get a sense of Mexican culture this year, whether on the encouragement of the UK-Mexico Year of Culture, or because you believe, like Goldman, that it is our responsibility as part of the international community to show solidarity with the Mexican people, let Mexico’s literatures be your mediator.

Thomas Bunstead and Sophie Hughes, East Sussex, England, and Mexico City, January 2015

Other noteworthy 2014/2015 publications by Mexican authors in English translation include:

- Mario Bellatín, Jacob the Mutant Paperback, translated by Jacob Steinberg and published by Phoneme Media

- Carmen Boullosa, Texas: The Great Theft, trans. Samantha Schnee (Deep Vellum)

- Álvaro Enrigue, Sudden Death, trans. Natasha Wimmer (Harvill Secker/Riverhead, Penguin)

- Luis Felipe Fabre, Sor Juana and Other Monsters, trans. John Pluecker (Ugly Duckling Presse)

- Yuri Herrera, Signs Preceding the End of the World, trans. Lisa Dillman (And Other Stories)

- Laia Jufresa, Umami, trans. Sophie Hughes (Oneworld)

- Valeria Luiselli, The Story of My Teeth, trans. Christina MacSweeney (Granta/Coffee House Press)

- Guadalupe Nettel, The Body Where I Was Born trans. J. T. Lichtenstein (Seven Stories)

- Sergio Pitol, The Art of Flight, trans. George Henson (Deep Vellum)

- Elena Poniatowska, Leonora, trans. Amanda Hopkinson (Serpent’s Tail)

- Daniel Sada, One Out of Two, trans. Katherine Silver (Graywolf Press)

- Daniel Saldaña Paris, Among Strange Victims, trans. Christina Macsweeney (Coffee House Press)

- Juan Villoro, The Guilty, trans. Kimberly Traube (George Braziller)

- Juan Villoro, God Is Round: Tackling the Giants, Villains, Triumphs, and Scandals of The World’s Favorite Game, trans. Thomas Bunstead (Restless Books)