It's not just the dearth of young girls in sailor uniforms with big eyes, tiny noses, and hair so long as to render actual movement nearly impossible that separates Akino Kondoh's work from that of most Japanese manga. Trained as a fine artist, Kondoh moves from manga to animation to painting to sculpture, and these different practices come back to inform her manga, most obviously seen in the movement that fills the pages of her comics. She is one of few manga artists in Japan who is just as involved in the world of fine arts as she is in the world of comic arts. Whatever medium she is working in, however, she always comes back to her “ideal girl,” Eiko, whose narrow eyes and light lines are reminiscent of the women of traditional Japanese ukiyo-e, those old woodblock prints depicting life in the pleasure quarters of the old cities. But Eiko is thoroughly modern, living in her tiny apartment in what one assumes is Tokyo.

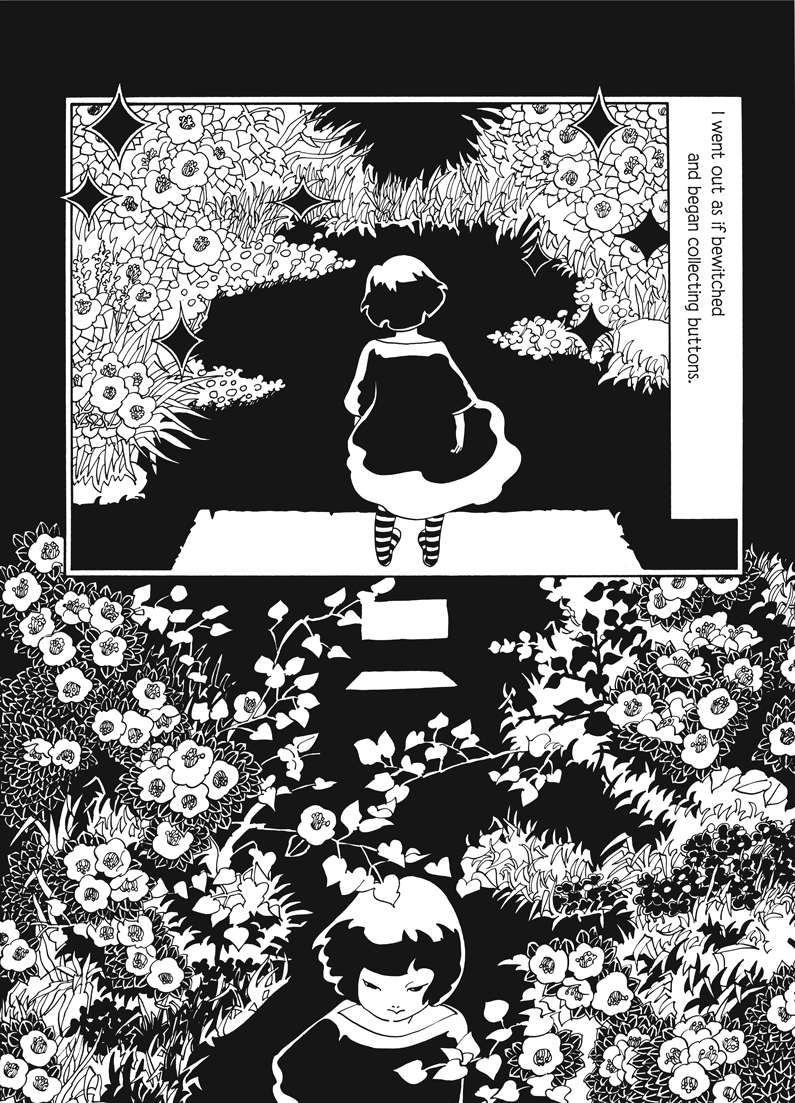

The cramped quarters of that city (and of Japan in general) are reflected in Kondoh's work, with motifs like closets and boxes popping up over and over again. Eiko is often depicted performing small, everyday acts, like clipping her nails or getting out some underwear, activities from which she suddenly escapes as her confined everyday world opens up into expansive new spaces: a city in her dresser drawer, hundreds of copies of her own self dancing around her in the rain.

Focusing so thoroughly as it does on this transformation of the mundane into the magical, “Ladybirds' Requiem” is possibly my favorite of all Kondoh's stories. Although much of her work deals with insects and metamorphoses, the way she takes something as simple as killing a ladybird with her curtain and turns it into a grand gesture neve fails to make me think about myself and my relationship with the world around me. I admire Kondoh's concise, simple sentences, and the way they pair so well with the minimalist drawing style she favors.

However, when I went to translate the story, I was reminded again of how deceptively complicated simplicity can be. Finding the words in English to convey the somewhat matter-of-fact tone of the Japanese, while still teasing out the sly humor and lyricism was hard enough. When translating manga, you always have to be aware of those little boxes and bubbles into which your words must fit. Those words are printed on a page, like a novel or a short story, but the constraints imposed are similar to subtitles for a film. This kind of translation is its own art, much like the original manga: not text, not comics, but something more than both.

One especially devilish example of this simplicity is the funeral gift Eiko gives to the ladybird: o-koden, an envelope of money brought to funerals as an offering to the dead person. Most people in North America do not bring envelopes of money to funerals. Or to any event really. But the custom in Japan for nearly every major event–weddings, births, deaths–is to give an envelope of money. The type of envelope and the amount of money depend on many factors, and getting all this right is the subject of many etiquette columns. So how do you translate a word for which even the concept barely exists in English?

I took to Twitter, my go-to place when I am wondering about actual English word usage. One follower noted that you often bring food and flowers when someone dies, but this clearly does not work in this situation. “Sympathy gift” was suggested, but I felt that that is for the grieving loves ones, while o-koden is an offering to the deceased. “Memorial gift” was close, and it was enough to start a Google search. After picking around through the results, I settled on “funeral gift.”

All of Eiko's efforts collecting the buttons and then sewing them into her skirt are done with a sense of respect and a satisfaction in the work itself. Getting just the right word here was essential to me, since the mood and the weight of the story depend on this line. These gifts of money in envelopes have to be returned to the giver in the form of an actual gift of some kind: a lacquerware tray, a set of porcelain cups, a hand mirror. So using “funeral gift” here made the “return gift” of the last line possible, even if conveying the full weight of those two words is impossible in a language without such customs.

Of Kondoh's many stories featuring Eiko, only one other has been translated into English so far (in Ax). I want more. I want people to have a have a chance to see more of her intricate yet expansive world. I hope that this story in Words Without Borders triggers an avalanche of delicately penciled bugs and boxes and buttons in bookstores all over North America.