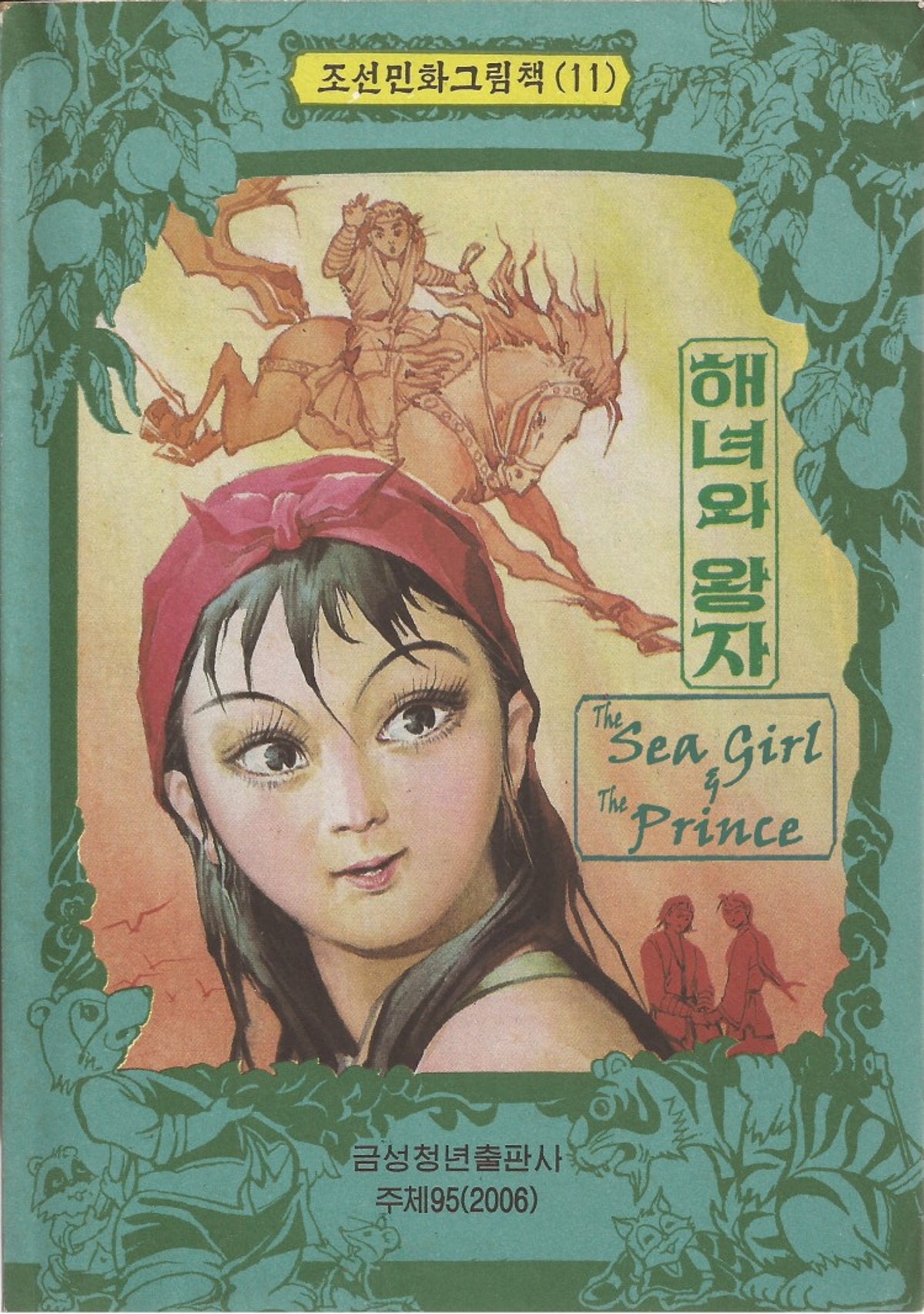

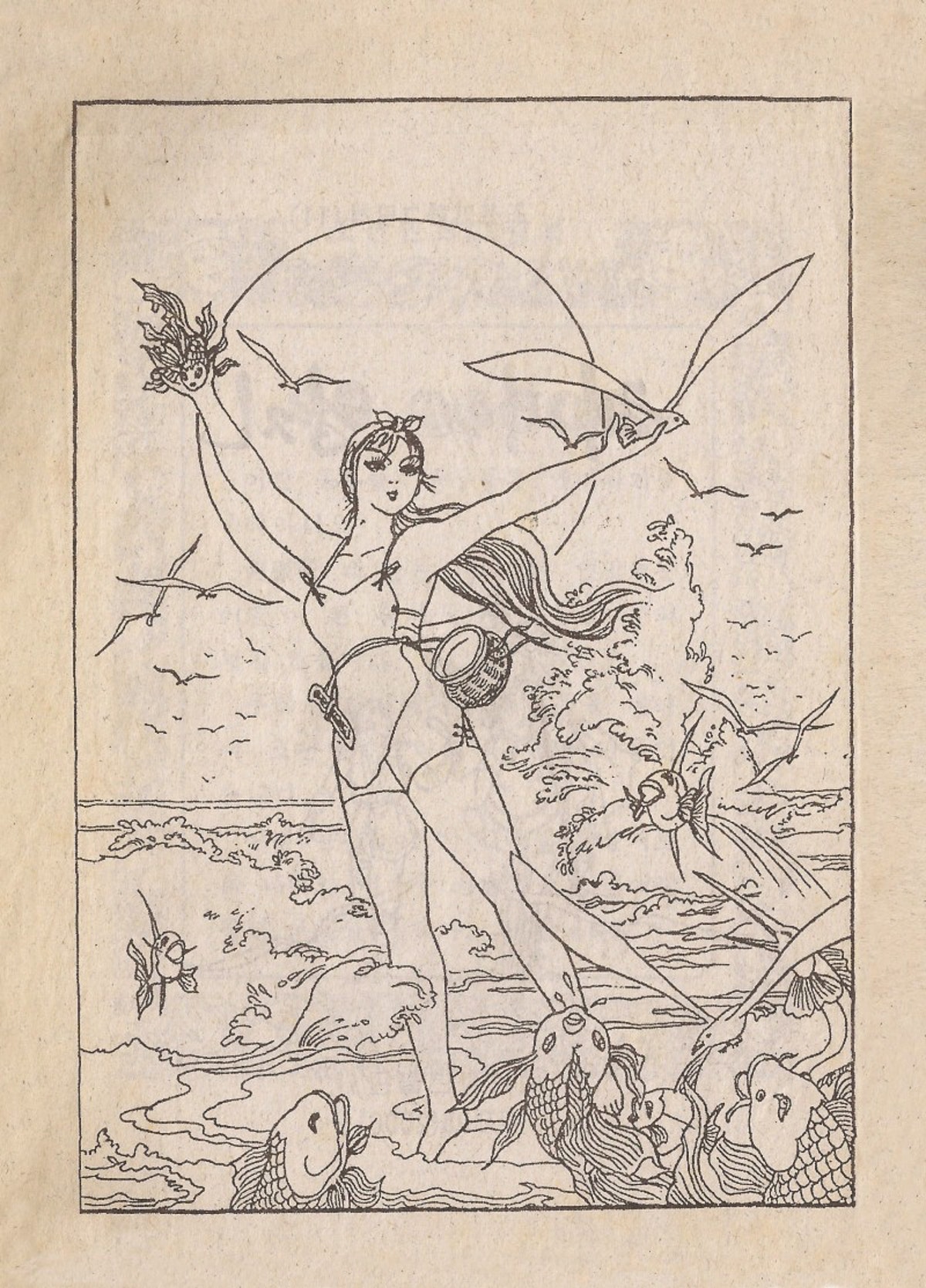

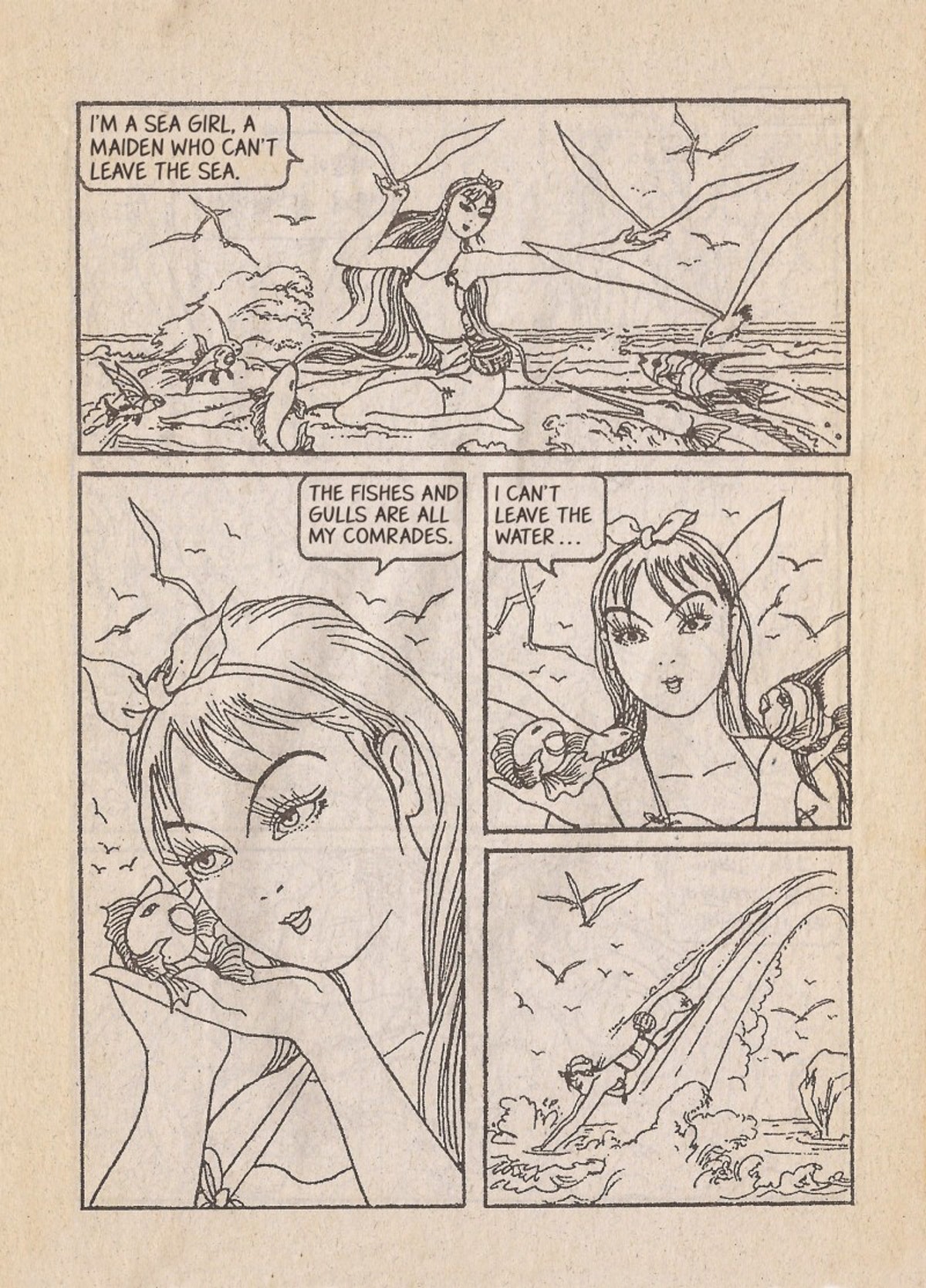

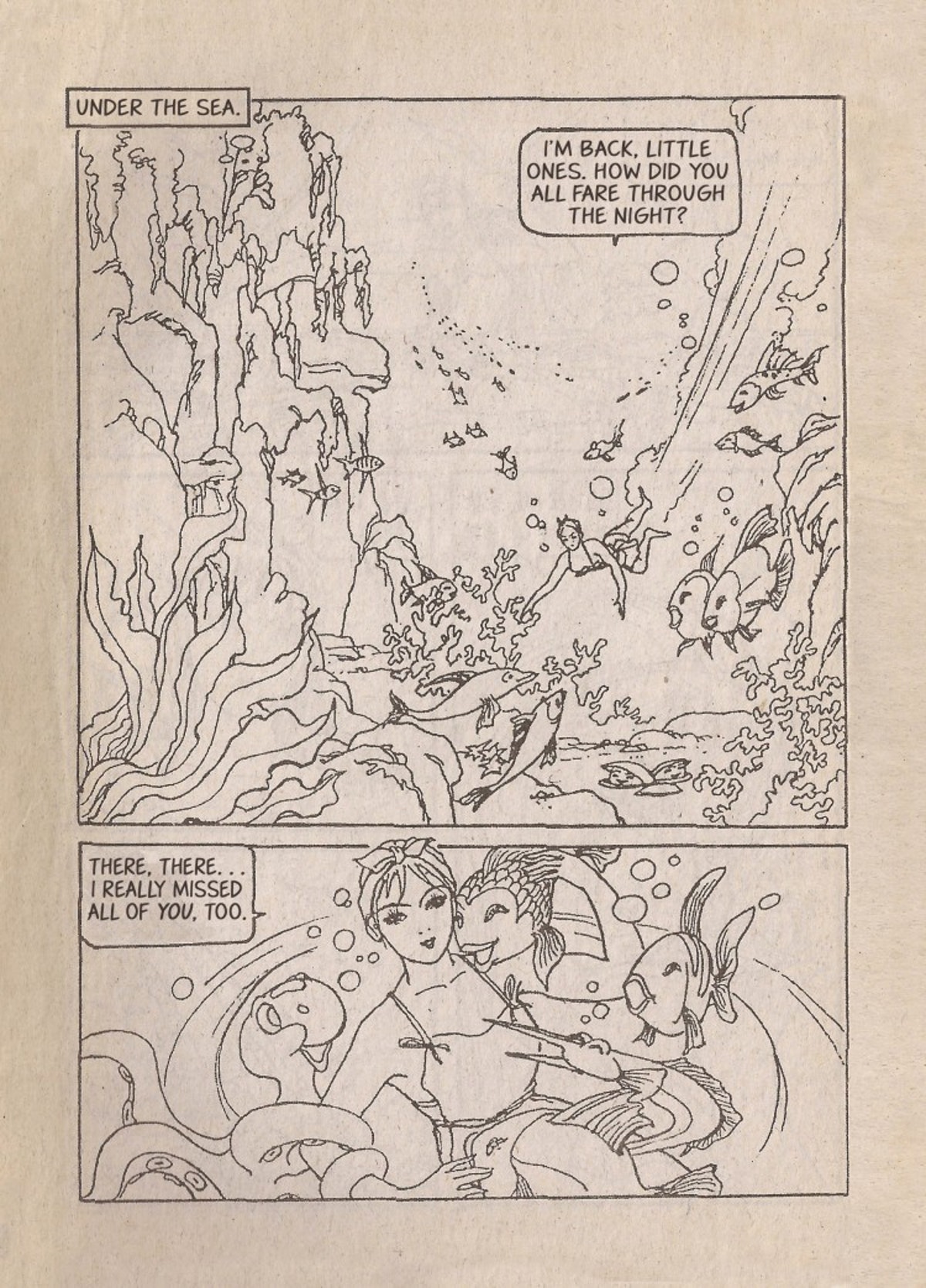

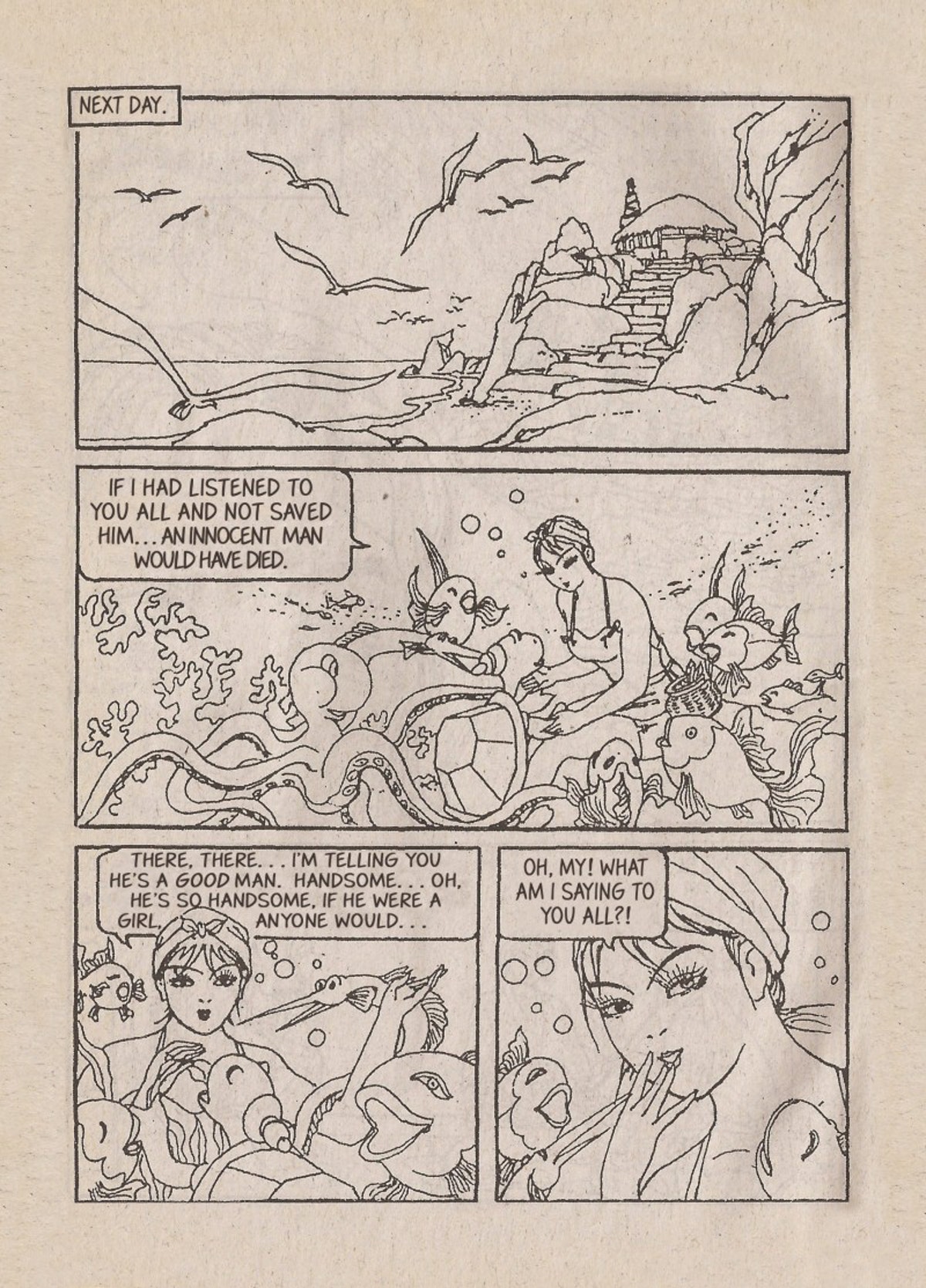

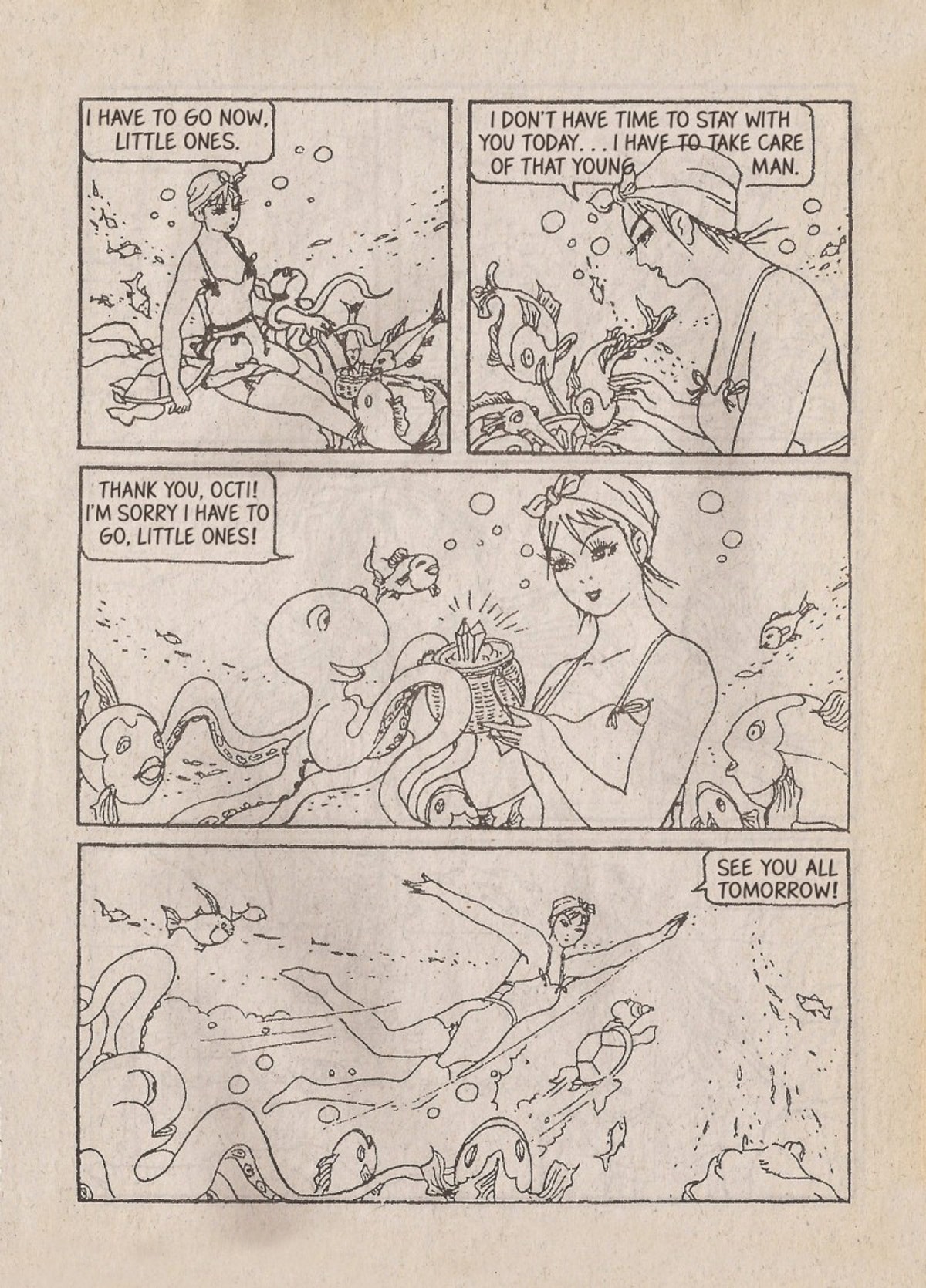

At first glance, The Sea Girl & the Prince would appear to be a retelling of Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Little Mermaid,” but it is almost nothing like it. The Sea Girl & the Prince shares more similarities with the Disney film The Little Mermaid. But while the titular Sea Girl does talk to anthropomorphic animal friends (and seems to breathe underwater), she is not a literal mermaid—she is a figurative mermaid based on the women divers of Jejudo, a small volcanic island off the southern tip of the Korean peninsula. Sea Girl is a literal “sea girl,” part of a long, real-life tradition of strong women who have been central to the economy and culture of the people of Jejudo until recent times. In that way, she fulfills the role of a realistic and strong woman character deemed necessary to romantic narratives by the Juche theory of literature created by Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il (an aesthetic ideology similar to Soviet Socialist Realism).

The Prince in Sea Girl does not even know he is a prince until near the end of the story, and there is no sea witch (although the villain of the story is a queen reminiscent of the one in Disney’s Snow White). The creators of Sea Girl clearly had access to Disney films, and also responded to the reunification allegory in the 2005 animated feature film Empress Chung, directed by Nelson Shin, which was the first South/North Korean co-production. Empress Chung also drew on a mixture of Korean folklore and Disney films for its source material, and its uplifting wedding ceremony at the end was an overt call for a peaceful reunification of the peninsula.

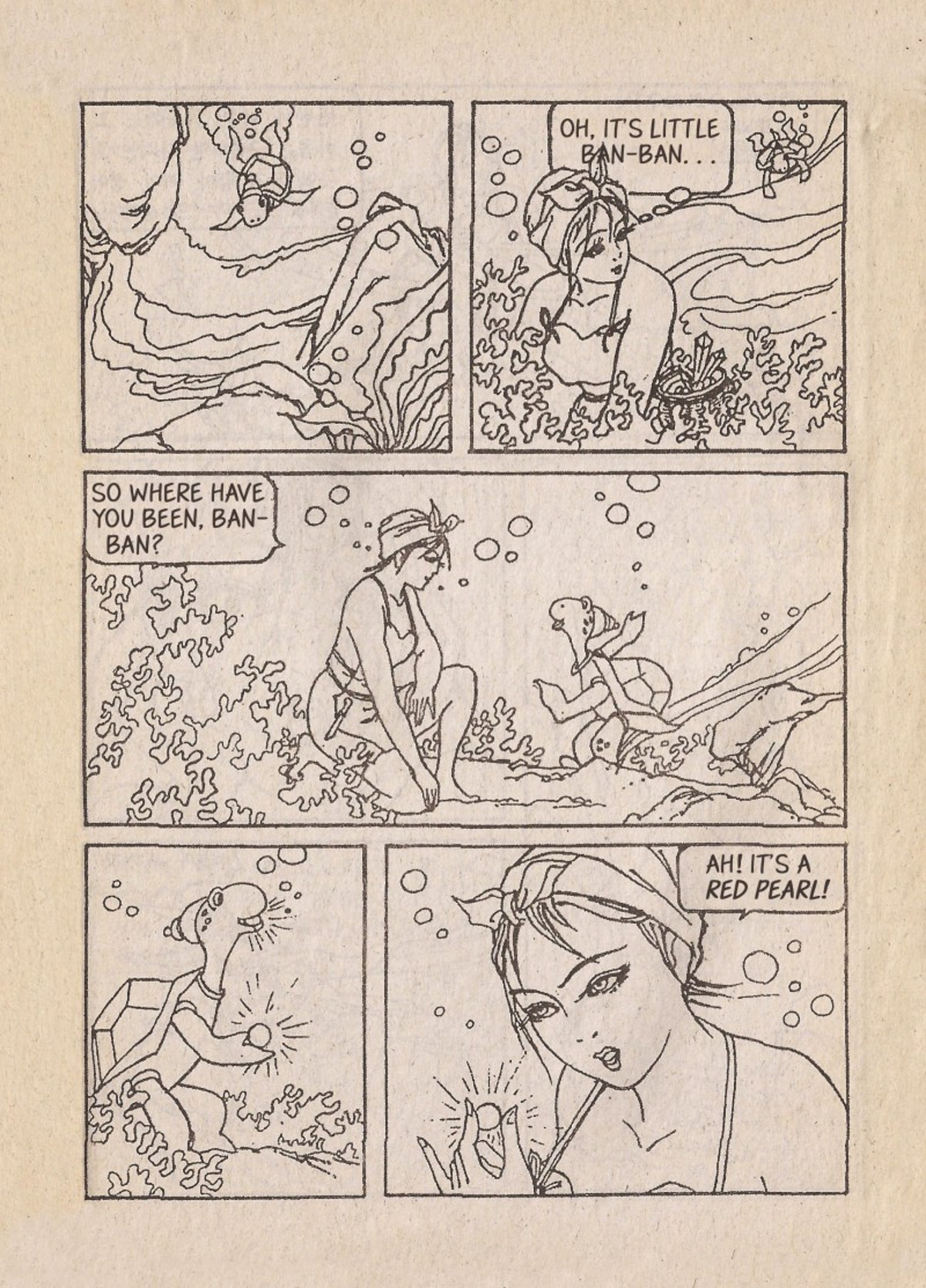

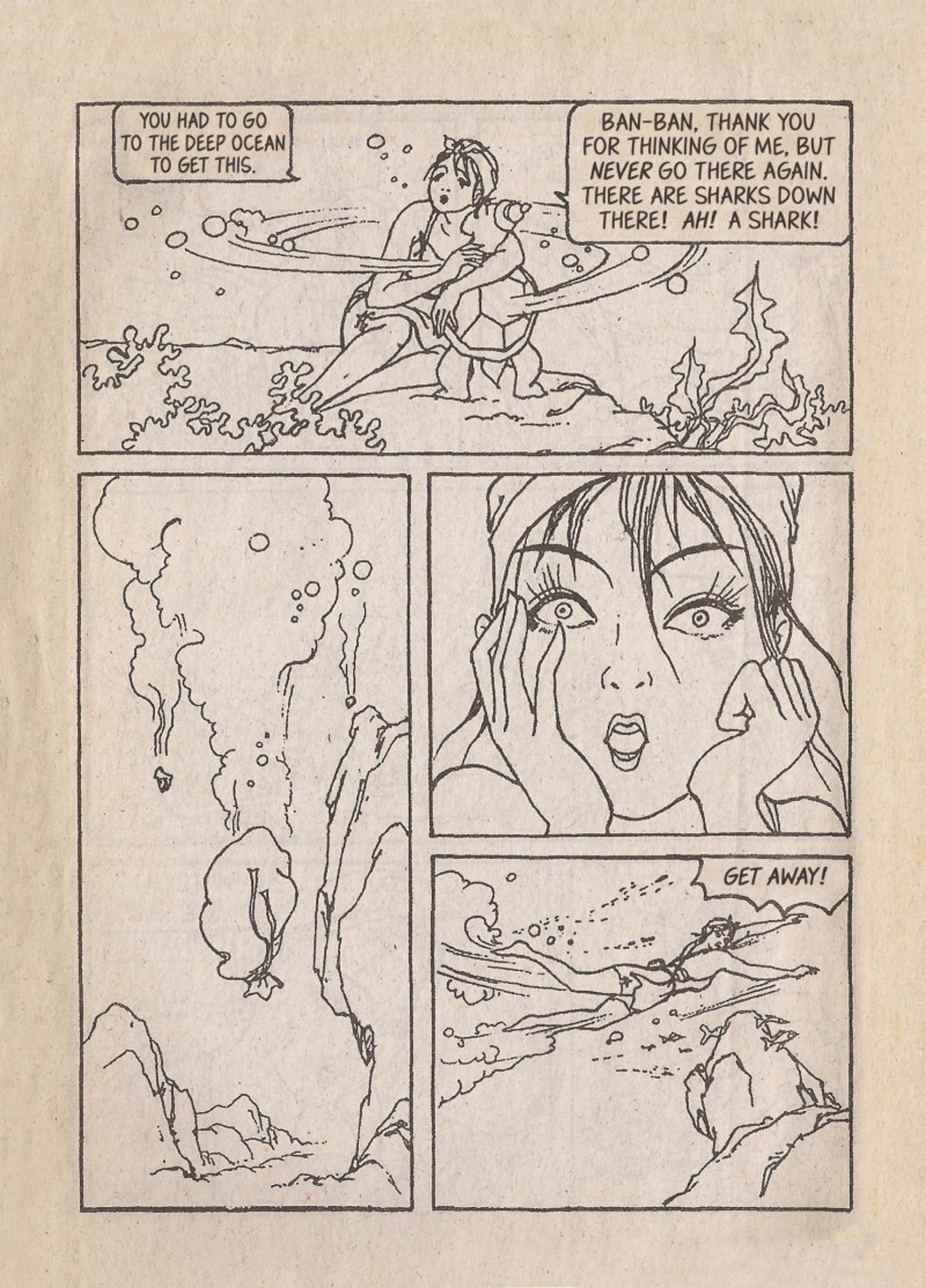

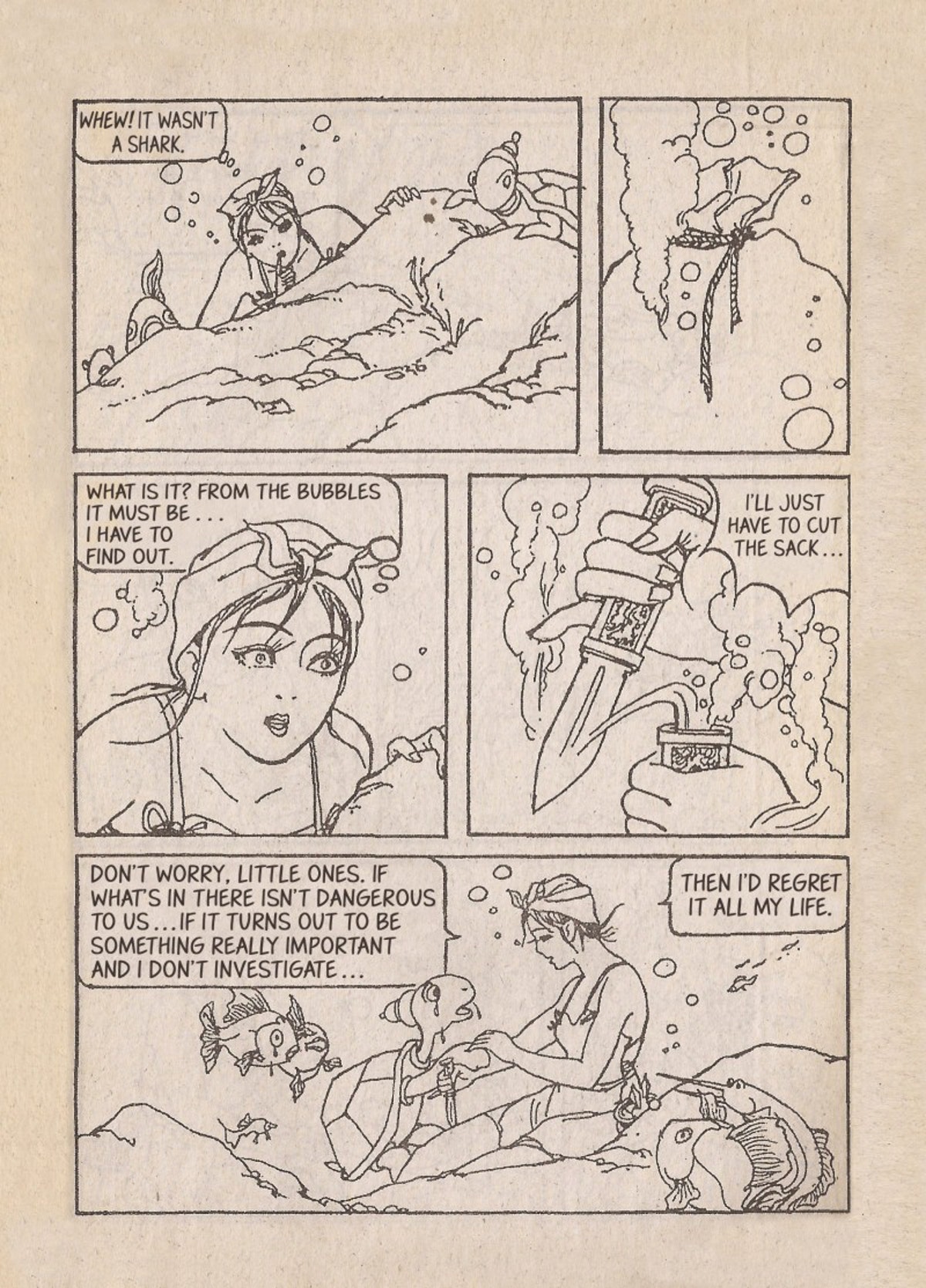

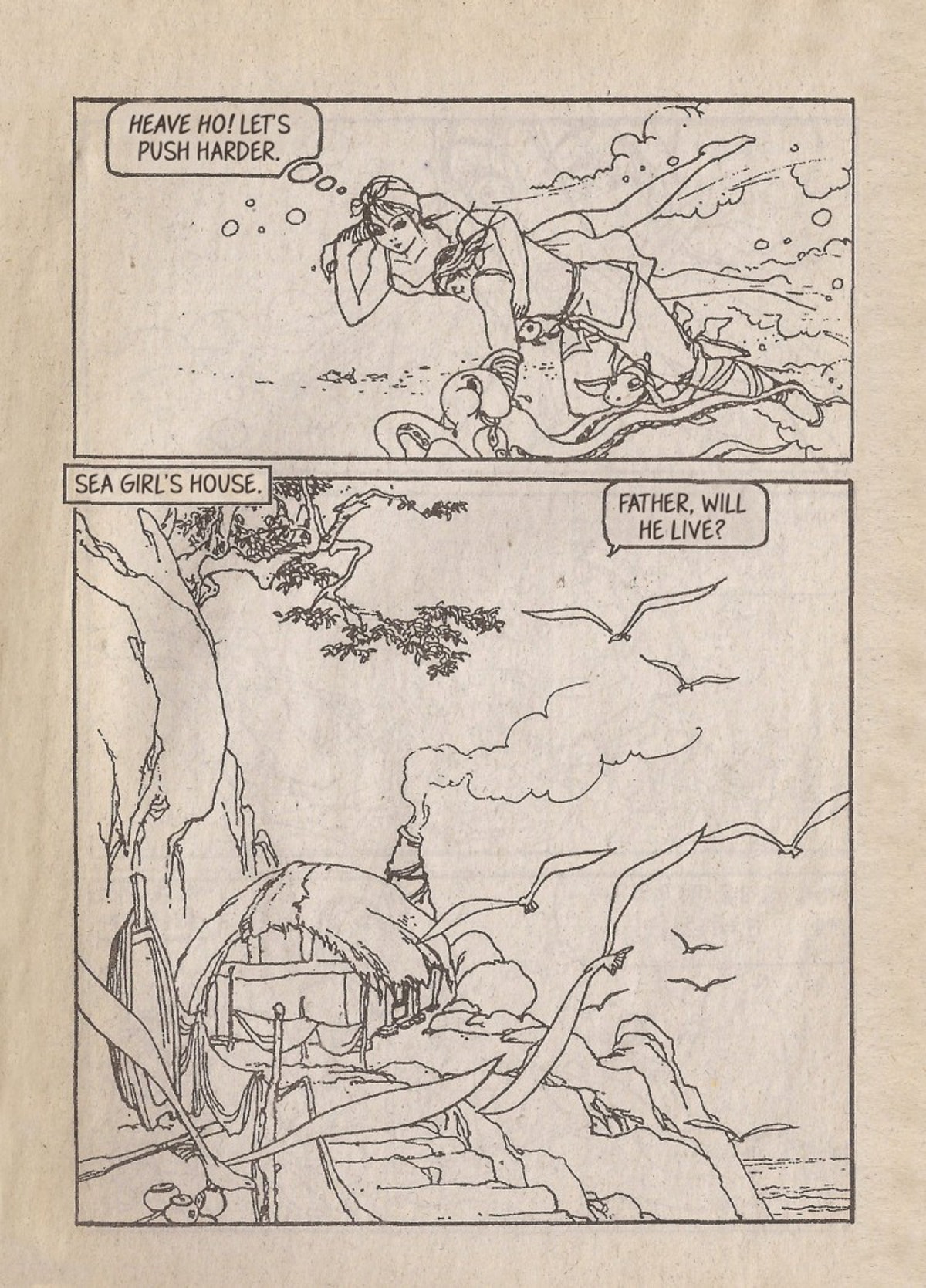

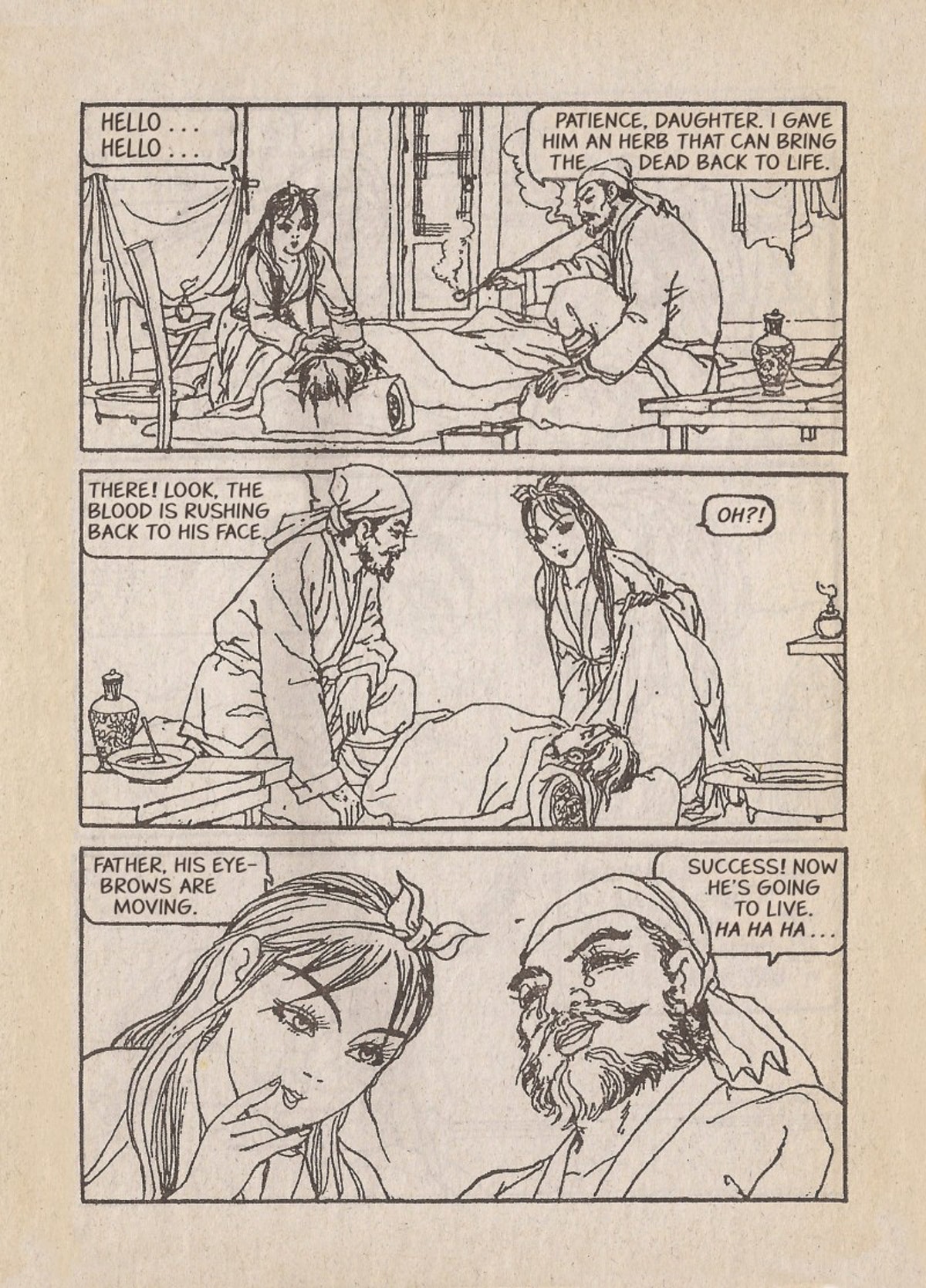

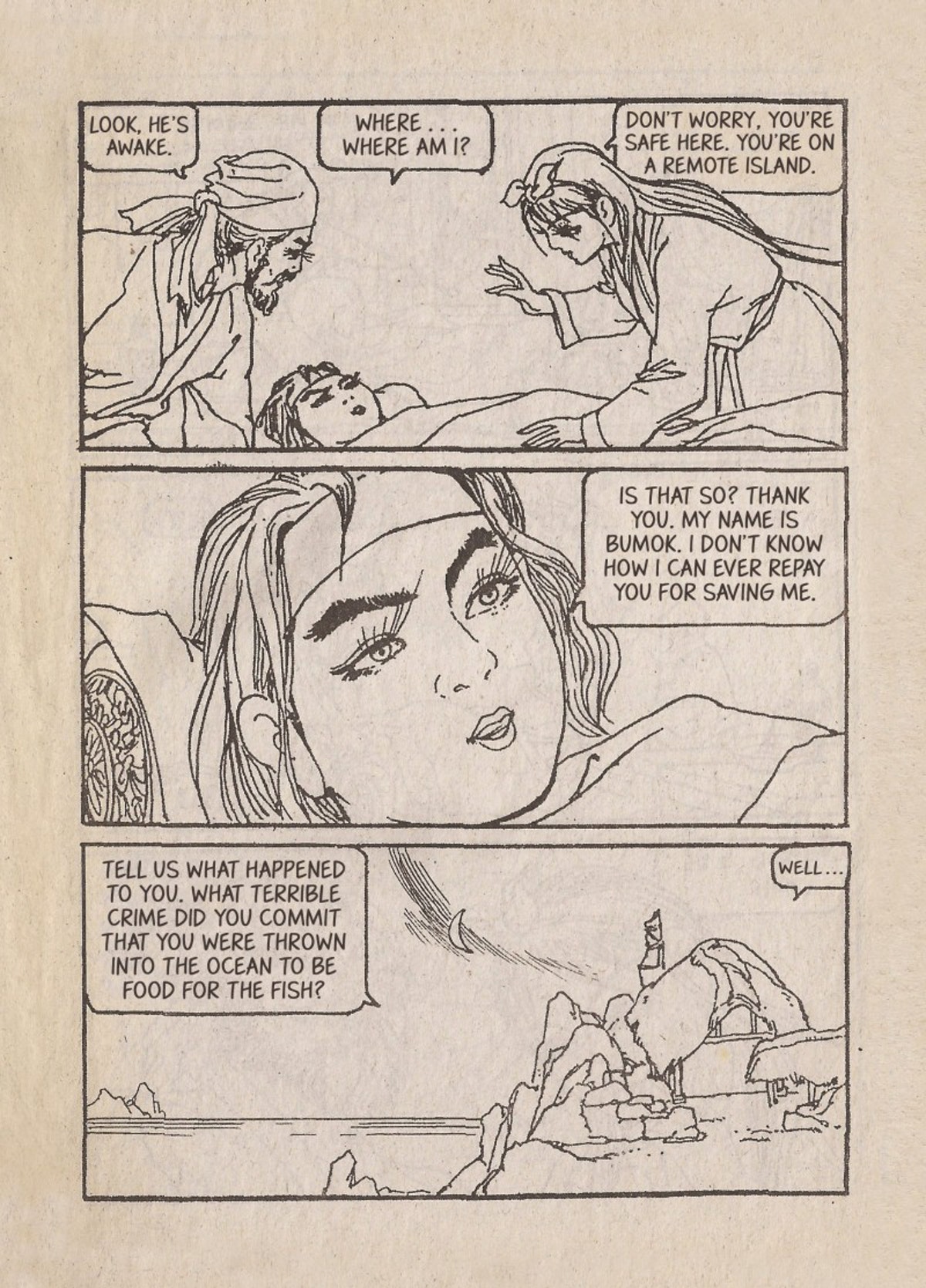

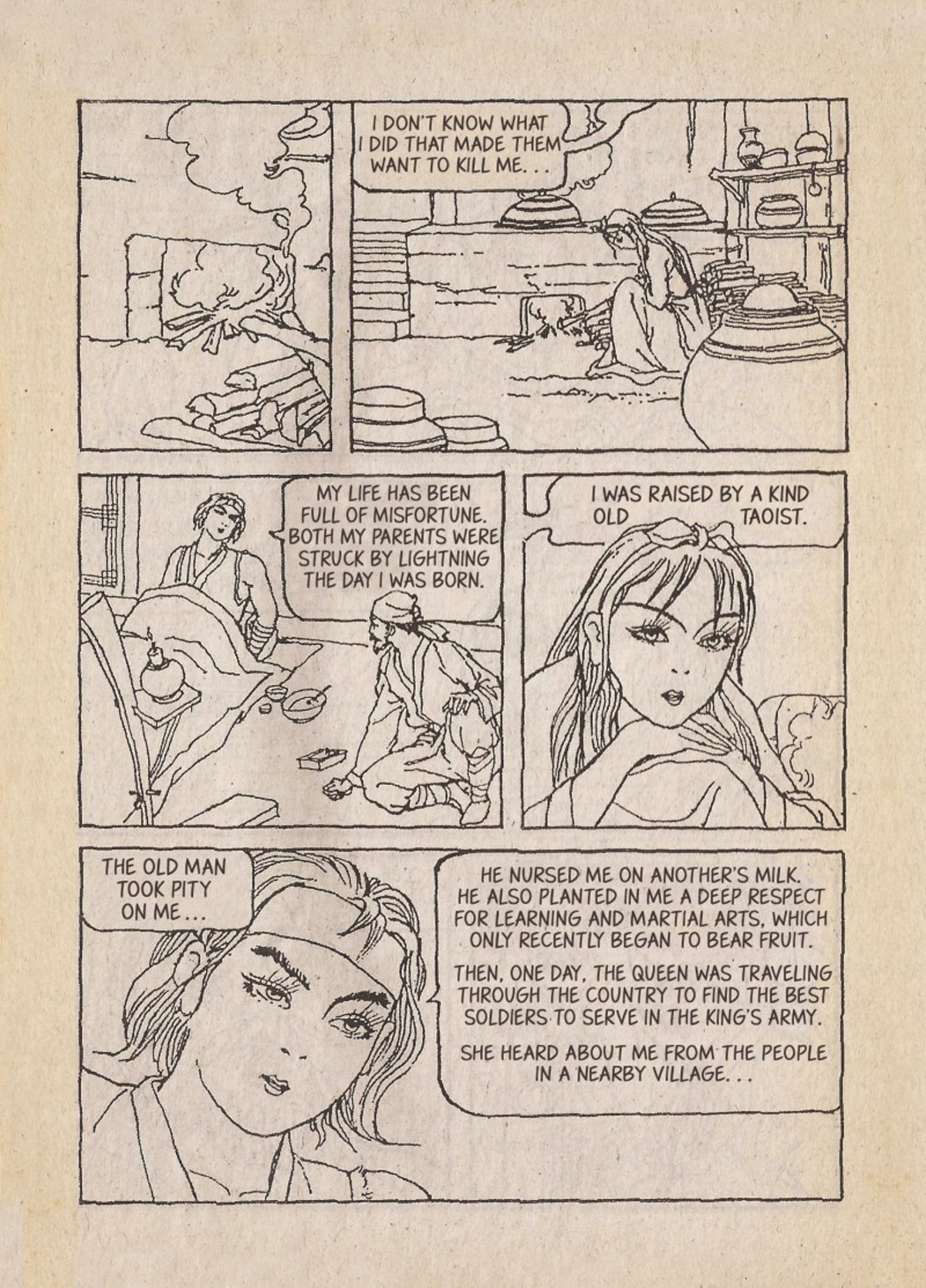

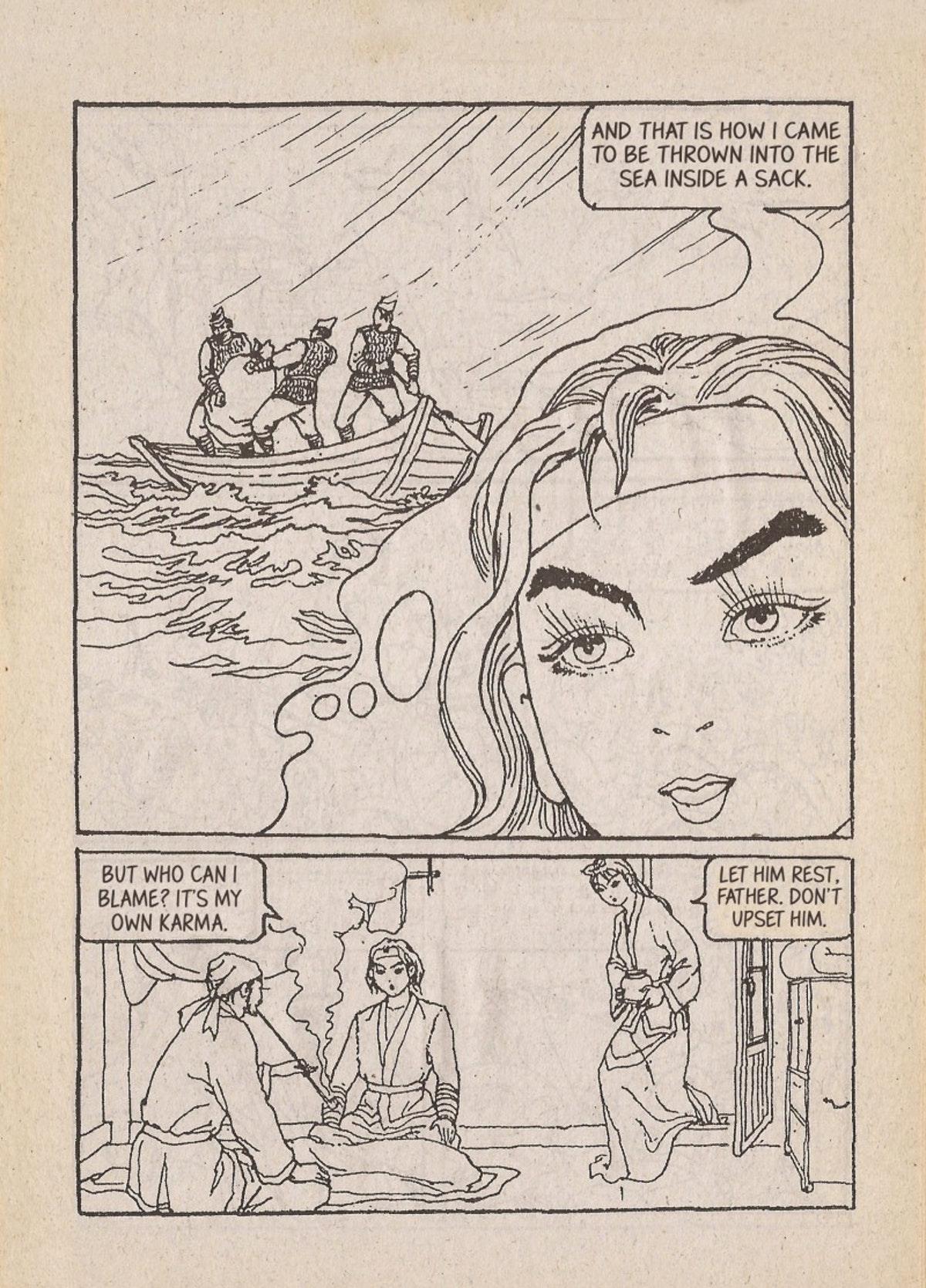

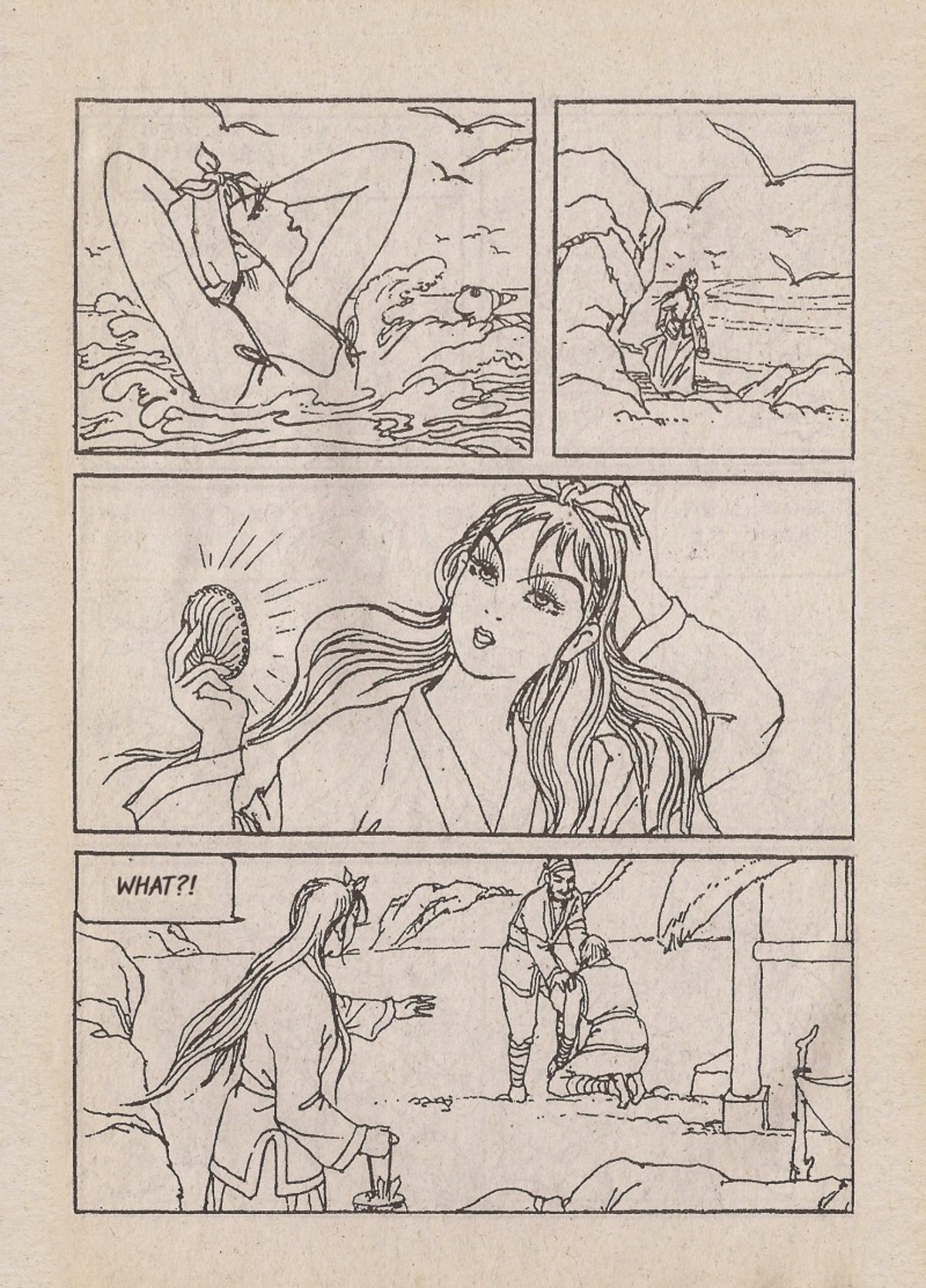

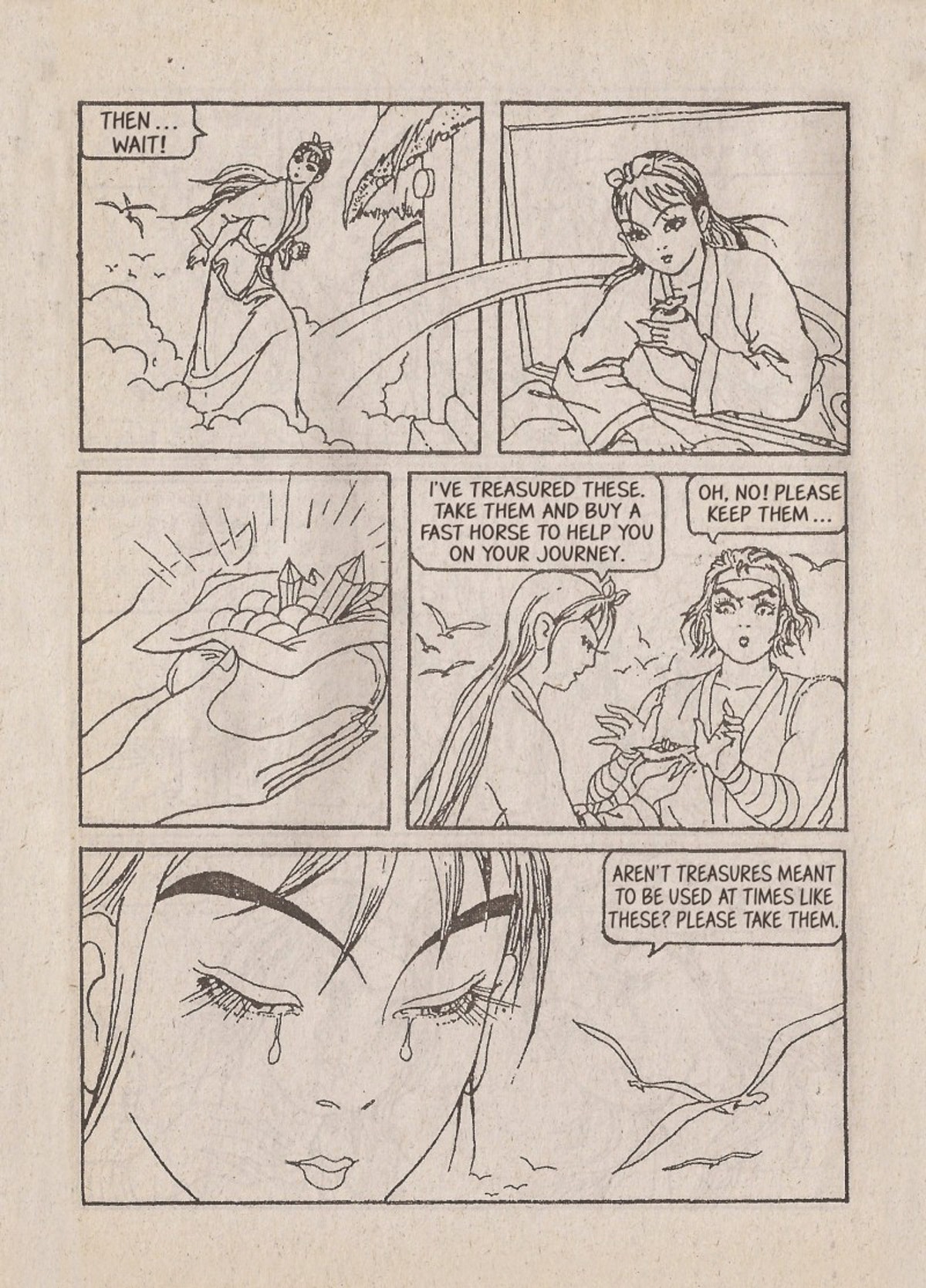

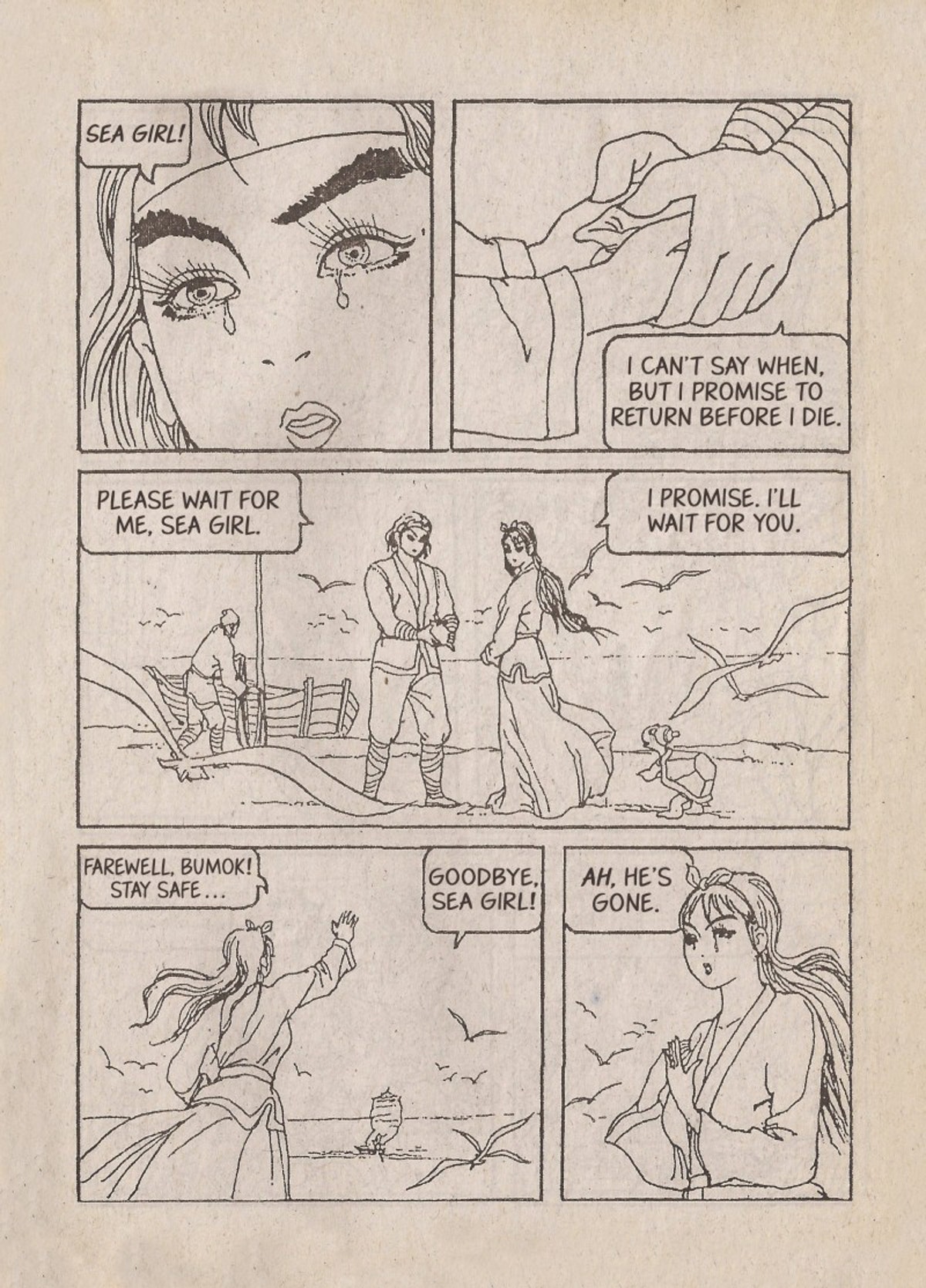

Aside from the ideology-laden introductory page, The Sea Girl & the Prince is stylistically similar to the Shoujo manga produced in Japan and the romantic serial stories characteristic of South Korean manhwa in the 1960s. Most of the propaganda is subtle: at the end of the story, when it turns out the Prince is the long-lost son of the King, the King expresses regrets about not having raised him at court. But one of the King’s advisers says that it was a good thing. Being brought up in obscurity by an old Taoist, the prince was raised by the people and is thus the child of the people. The Prince’s love for them is authentic—as equals—and they in return will love him when he rules the kingdom. In fact, much of the plot of Sea Girl revolves around equanimity. In this excerpt, Sea Girl saves the Prince from drowning, but near the end of the story, the Prince will save her. Bereft because of the evil Queen’s trickery (which has made Sea Girl believe the Prince has abandoned her for another woman at court), she will go blind and try to kill herself by leaping from a high precipice into the ocean. The Prince is able to save Sea Girl only because she gave him her sea jewels, which he used to buy himself a swift “dragon” horse.

The Sea Girl, from Jejudo (the very southern point of South Korea), eventually marries the Prince (from the area meant to be Pyongyang, the capital of North Korea), and together they symbolically reunify the nation. The last page of the graphic novel is a repeat of the first page with the Prince added in the background.

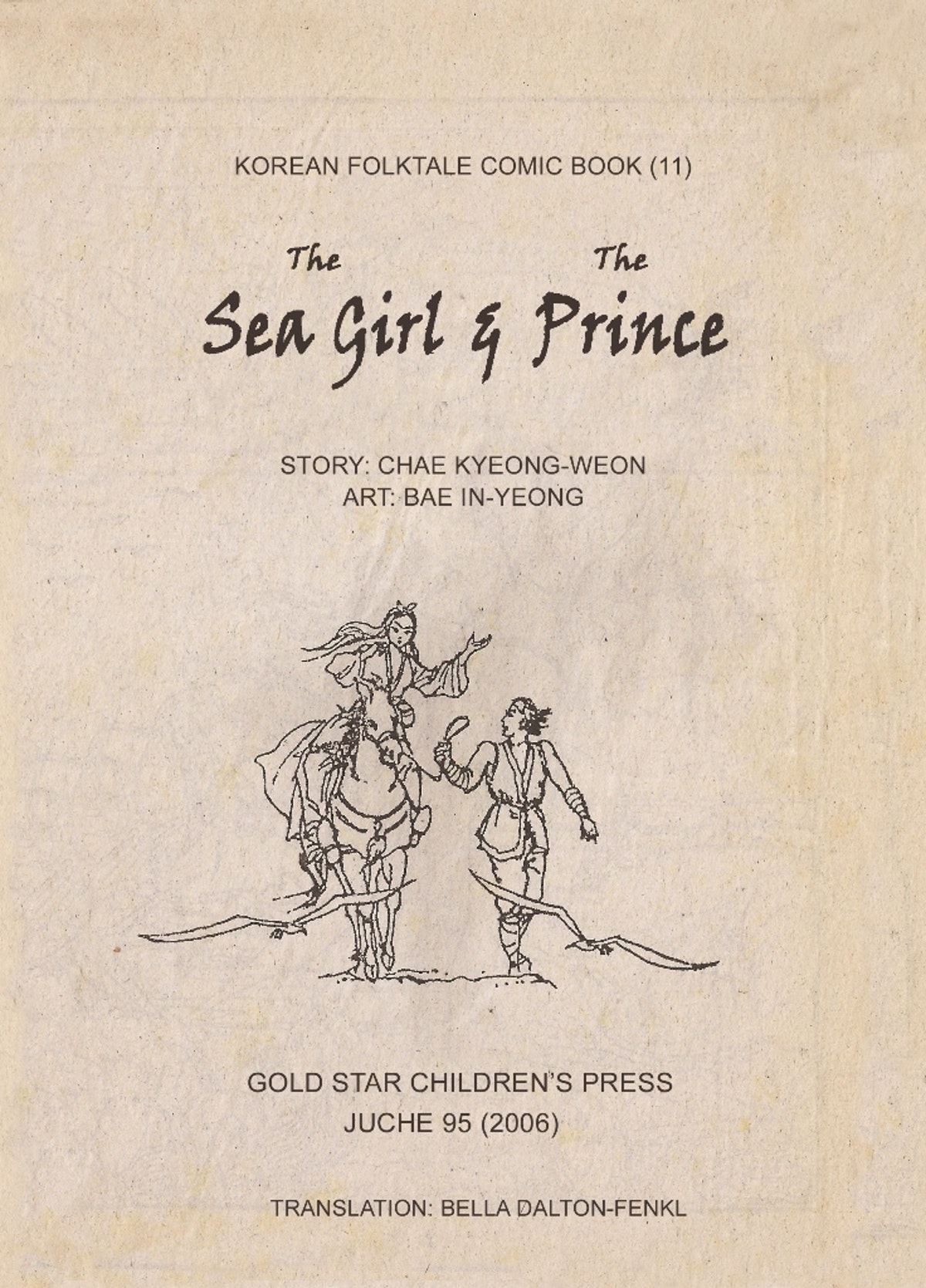

As is typical in North Korean publications, no information about the authors is provided. Because North Koreans write in the phonetic hangul alphabet and do not use Chinese characters, it is not possible to say with certainty, but the writer Chae Kyeong-weon and artist Bae In-yeong seem to be women. And yet, as with all things North Korean, there are layers of meaning and the names may be clever pseudonyms. When examined via corresponding Chinese characters, the name “Kyeong-weon” sounds like “sunny garden” or “guarded garden” (and also “keep a respectful distance”), while “In-yeong” sounds like the “imprint of an official seal” or the “shadow of a person,” and also (with a soft aspiration), “doll.”

“The Sea Girl and the Prince” © 2016 by Bella Dalton-Fenkl. Lettering and production by Heinz Insu Fenkl. All rights reserved.