The winter this year was harsh in Greece. Unprecedented snow fell on the Aegean islands, while temperatures in usually temperate Athens hovered around zero degrees centigrade for most of January. The television channels seemed to thrive on repeated footage of people’s hardships, but what made me shiver with horror were the scenes of refugees in flimsy clothes and sandals with only tents for shelter. Three on Lesbos even died in the blizzard.

Besides the pitiful films of refugees, the television news also featured images of Greeks clustered around a cauldron of bean soup in Monastiraki Square, hungry men and women shuffling in a long queue for a bowl of food at a municipal kitchen, jostling for sacks of free potatoes donated by generous farmers.

Suddenly, there did not appear to be many differences between foreign refugees and homeless, hungry natives, except that there were growing numbers of people volunteering to help and nurture both. Whereas shelter and safety must come first, the question of food is so fundamental. Yes, we all need enough to keep body and soul together, but if the body can subsist on handouts and scraps, what of the soul?

As the weather turned from glacial to mild, TV coverage of the dismal refugee situation focused on riots at Elliniko, the site of the old airport and one of the main camps in the Athens area. This time the men, women, and children, who are being housed in what looked like deplorable conditions, used the visit of the Minister for Immigration to protest what they called “inedible and unacceptable food.” The camera zoomed in on plastic containers of an unidentifiable mush that appeared to be spotted with mold. They landed, untouched, in the garbage.

These images contrasted with stories run in the papers just before Christmas, perhaps as a nod to the season, about a Syrian chef who was cooking his country’s cuisine at Café Rits, in the Ritsona camp about an hour’s drive northeast of Athens. Ritsona houses some 700 refugees, half of whom are children, and the café, funded by a former investment banker from the United States named Carolynn Rockafellow, offers locally-sourced produce cooked with flair and spice to supplement the bland rations provided by the official caterer hired by the military. The Greek military, which runs the official camps in uneasy collaboration with NGOs—and with varying degrees of success—typically hires a caterer to prepare free meals at a cost of six euros per person per day. But at Ritsona, which has its own Facebook page, one can see videos of smiling faces and a man dancing as he serves meals that some of the diners have helped with—a far cry from the angry mob at the airport.

Amazingly, there are no reliable statistics on the exact number of refugees in Greece, although over a million have passed through the country. Most reports put the number at “more than 60,000,” but even the number of camps that are meant to be sheltering them is unclear. An article that appeared in the Guardian in early March painted a picture of the many factors that make a census of refugees problematic: some camps have been abandoned, many have far fewer residents than advertised, an unknown number of refugees have simply “vanished,” while countless others live in squats scattered in and around Athens. It paints a grim picture of the failure of the Greek state and the UNHCR to coordinate efforts to improve conditions in the camps and put to good use the vast sums of money that have poured into the country in aid of vulnerable refugees and their families.

Always on the search for glimmers of hope in situations that are invariably presented as relentlessly grim, I asked friends who work with refugees for their opinions. A dear American friend who lives between Athens and New Hampshire told me about her experiences at Ritsona and Oinofyta, where she was teaching illiterate Afghan women English; an Iranian friend started me on my quest with a visit to shelters in Victoria Square; a total stranger, a friend of a friend’s English granddaughter, here for a two-month stint as a volunteer, introduced me to the team at Khora; and a Greek friend took me with her to Eleonas, where she had organized a summer school for kids. I discovered a volunteer network of extraordinary range and depth, as well as refugee communities where hope was still flickering.

The Eleonas camp is located in a dusty area of semi-abandoned factories and transport companies on the Iera Odos, the Sacred Way that still connects the center of Athens with the ancient pilgrimage site at Elefsis. It was the first camp to be created in the metropolitan area, in 2015, in an attempt to house refugees who were sleeping rough in Athenian parks.

The Eleonas camp. All photos by Diana Farr Louis

On a sunny Monday in early March, the complex of containers—looking not unlike a US trailer park without the trees and RVs—where perhaps 2,000 people live, did not seem as forbidding as I’d expected, having read about insufferable summer heat and winter chills. Instead, the main “street” had the open feeling of an island neighborhood. On one side, behind a row of plastic Christmas trees, some men were hunched over a backgammon board; people of all ages were strolling; young men were kicking a ball around a new bright-green soccer field (in better shape than those at most Greek public schools). A volunteer followed by a stream of kids invited us to a magic show in one of the big tents near the entrance.

Mahrooz, a slender seventeen-year-old from near Kabul, was waiting for my Greek friend and me. Poised, confident, and intelligent, she would be our interpreter. She confessed in fluent English that although she’d studied it in school, she’d only dared to start speaking it after she arrived in Greece—exactly 364 days earlier. It’s her fourth language after Pashto, Farsi, and Hindi. Mahrooz guided us to the container where Soraya, her compatriot, lives with her two young daughters and teenaged nephew.

We took off our shoes, padded up the two steps into the cozy kitchen and greeted Soraya, who was stirring a stew in an electric crockpot. A fridge stood in one corner of the room, flanking the bed. Across from the stove were a bin with onions and potatoes, a vacuum cleaner, and a pile of dolls and other toys. Anticipating our visit, Soraya had already fried a couple of flat, round Afghan cheese pies with a light sugar glaze. We tore off strips from one and asked how she’d made it. Soraya whisked a fat rolling pin from behind a door and mimed rolling dough out on the floor.

After boiling some water for tea in her electric kettle—she paid for all the appliances herself—Soraya “set the table,” laying a white cloth on the floor in the other room and placing dates and fruit on it, along with the cookies we had brought. Mahrooz told us, “In Afghanistan when guests drop in, it’s a rule, we have to put out everything we have.”

We settled ourselves around the cloth and continued talking about food. Yes, the camp does distribute packaged breakfasts, lunches, and dinners, but while the food isn’t moldy, it has “absolutely no taste . . . whether it’s lentils, spaghetti with tomato sauce, or white rice topped with white chicken and no sauce at all. We’ve stopped taking it. The only things we accept are the buns and juice they bring for breakfast.”

Most of the residents, Mahrooz told us, who get a monthly stipend from the International Rescue Committee (€90 for a single person, €270 for a family of four to six, and €330 for more than six), prefer to shop and cook for themselves. They enjoy taking the camp bus to Omonia Square in the heart of Athens and finding bargains at the Central Market. They can even buy most of the spices and chilies they love at the Pakistani shops on Menandrou Street in the same neighborhood.

“There was a rumor going round,” said Mahrooz, “that in March they’re going to stop making the food we don’t eat and give us the money instead, but we’re already into March and there’s no sign of that happening.”

We sipped our tea and tried not to devour the second pie. Soraya bought out a cabbage and, still sitting on the floor, proceeded to slice it with some carrots for a kind of Afghan cole slaw. Before long Mahrooz’s fourteen-year-old sister joined us and took over the mixing of the salad, to which Soraya added some mayonnaise and homemade yogurt, along with cumin, pepper, and dried mint.

Soraya stepped back into the kitchen to get her vegetable stew. Distraught when she learned we had to leave before lunch, she ladled out some for us—“at least to taste.” The zucchini, after long cooking with olive oil, onions, tomato, and some untranslatable spice, was so succulent we kept having just one more spoonful, in a fruitless attempt to identify the seasonings.

Before we left, the girls whipped out their phones for a round of group selfies. My first encounter with refugee women was more like a visit to an Afghan village than a camp. Our hostesses behaved as they would in their own country, giggling, offering hospitality, and showing off their kitchen arts and talents to guests.

If you have to be stuck in a camp, Eleonas is clearly one of the better ones. With complete freedom to come and go, residents are within easy reach of Athens and can keep their self-respect. Kids can go to school and plenty of programs exist for adults too.

Oinofyta, north of Athens, enjoys a similar reputation. The primarily Afghan population there has organized itself into a community and, with the help of volunteers, headed by a forceful American named Lisa Campbell, they have been able to regain their pride by doing things for themselves, from carpentry to cooking. Far from the city, they are almost as homogeneous and self-sufficient as a village in their own country. And they are safe.

Even so, perhaps the most fortunate refugees are those who have found a semblance of normalcy in their own housing, whether in squats—abandoned buildings—rented apartments, or even hotels. Besides having the luxury of being independent, they are close to the city’s amenities and to the special services set up expressly for them. Most of these seem to be in the vicinity of Victoria Square, which was where the refugees congregated after they arrived in Piraeus from the islands. At one point there were tales of so many refugees sleeping in doorways that Greek residents could barely enter their apartments. But this was before March 2016, when Macedonia closed its borders. Many of the refugees in Greece at the time considered themselves in transit, and were planning to push north in hopes of attaining the promised lands of Germany and Scandinavia.

With the Macedonian border closed and the route north effectively barricaded, more practical long-term accommodation had to be found to supplement the camp at Eleonas. The City Plaza hotel near Victoria Square had long lain empty, a victim of the Greek crisis, when a group of leftists/anarchists claimed it in the name of homeless refugees. As reported in Al Jazeera, since April 2016, the seven-story building has been sheltering some 400 people, almost half of them children, in a well-organized experiment that relies solely on private donations and is unaffiliated with any government ministry or NGO. A series of amusing YouTube videos with titles like “the fastest vegetable chopper/slicer in the world” help the residents raise money, as do the impressive meals cooked by guests and volunteers in the hotel kitchen.

In fact, around Victoria Square twenty places that provide assistance ranging from baby bathing to legal, medical, and psychological support are listed in an eight-page leaflet along with a map showing their location, languages spoken, and services offered in English with symbols anyone can understand. Even so, their efforts probably don’t reach a fraction of those in need.

Only a few of them provide food or deal with questions of food.

The international Catholic charity Caritas has been offering valuable social assistance to migrants and refugees in Athens since 1987. They run three different centers near Omonia Square, one of which houses a highly organized soup kitchen, where many of my friends and acquaintances volunteer.

But because I was looking for a place where refugees rather than long-time residents are actually cooking for each other, I turned to Khora Community Center, which opened in November 2016 in Exarchia. This district, despite having a well-deserved reputation for anarchist vandalism, has also become the center of a number of imaginative, alternative humanitarian ventures.

Stepping into Khora’s reception area on the ground floor of a seven-story former print shop, I was greeted by a bustling, congenial atmosphere. My young English “guide” waved from the other side of the room and took me on a tour. Everyone, regardless of origin, seemed to be wearing a smile, and many of the regulars embraced her as we passed on the stairs. Volunteers and refugees, who are always referred to as “guests,” mingled in the dining room on the third floor, hanging out over cups of tea between meals.

The floor below is given over to a spacious kitchen. Volunteers take turns peeling, chopping, cooking, and washing up. Six days a week, they prepare breakfast (for 60), an afternoon snack (for 80), and a main midday meal for some 300 to 400, a figure that once soared to 550. A whiteboard leaning against the far wall lists the week’s duties, menu, and chefs, who may be British or Czech, Syrian, Baluchi, or Afghan. Other volunteers serve guests at long blue, red, and orange tables upstairs, where the wall paintings—stars, kites, abstract patterns against a purple or turquoise background, for example—seemed designed to evoke freedom and joy.

A horizontal organization run by volunteers, Khora has no chiefs and relies solely on donations from individuals or organizations like Help Refugees, a UK charity, or Thighs of Steel, a cycling club that funded their rent for a year with sponsored rides from London to Athens and will do the same again this summer. Julia Shirley-Quirk, one of the young core members, explains: “No one person is in charge. About twenty of us are long-term volunteers, I don’t even know how many short-term people we have, and all of us do a hundred and one things, from organizing the kitchen to driving down to Elliniko, to the main warehouse [for nonperishable food supplies], and distributing it to the squats.”

Loading Khora’s van at the Elliniko warehouse.

The fresh fruit and vegetables are bought locally, from the farmers’ street market or the Central Market, and the meals are mostly vegetarian simply because costs can’t exceed twenty-five cents a portion.

The core group has experience feeding large numbers of people; many of them began as volunteers in England with the Bristol-based anti–food waste charity, Skipchen (Skip=Trash bin + Kitchen). Rescuing perfectly good produce from the skips, they cooked it and set up pop-up restaurants and “food ambulances” in that city, which dispensed meals to the hungry while creating community at the same time. Many of them also worked at the Jungle, the notorious refugee camp in Calais (since closed), before coming to Greece, where, with two other charities, Better Days and No Borders, they founded a camp in an olive grove in order to tend to the overflow from the nearby main camp of Moria.

When Moria was shut down and turned into a detention center, some of the Skipchen volunteers came to Athens and eventually discovered the abandoned printshop. They signed a lease, and went to work painting and fixing it up, concocting ad hoc solutions to problems as they arose, learning on the job. The brightly colored murals of flowers and animals in the rooms and in the stairwells contribute to the cheerful atmosphere, but most of the bonhomie comes from the apparently effortless good will, mutual respect, and genuine affection that seems to flourish between coworkers at Khora.

Jawed, a twenty-seven-year-old structural engineer from Kabul, tells me, “We are one family here, everyone does every job, and we are small. That’s why it works.”

Back home he used to cook for his mother on Fridays, “to give her a rest,” and his eyes light up when he describes the Afghan national dish, Qoboli, an elaborate festive pilaf with meat, raisins, nuts, caramelized carrots, and more, a version of which he’s made for lunch that day (without the meat).

His fellow guest chefs are all men. Afghan and Syrian women come to Khora for language classes, special activities for women with small children, the dentist, legal advice, even yoga, but they do not work in the kitchen. Fahad, from Syria, picked up his culinary expertise out of necessity: “I learned from life and intuition, living with a bunch of guys who knew nothing at all and working with No Borders charity on Lesbos.” His favorite dishes are stuffed vegetables and vegetable stews, to which, he tells me, he adds hot pepper, cinnamon, cumin, mint, coriander . . .

Everyone agrees that the Afghans like it hotter than most. And so do the Baluchis. Yunis and Samir, activists from Baluchistan, which is claimed, variously, by Iran, Pakistan, and Afghanistan, loved to cook back home, where it’s traditionally a man’s job to prepare the food for wedding feasts and picnics. Both of them pull out their phones to show me photos of casseroles bubbling in a vacant lot, naan wrapped in foil for baking in hot coals, chicken ready to be baked in a clay pot sealed with dough. With mouth watering, I promise to come back another day and taste their chickpea stew and potato pie topped with seasoned yogurt (which proved to be as good as anticipated).

In a way Khora, whose name in Greek means “main town on an island,” is unique. The people who set it up and run it are almost all non-Greeks and very young (as opposed to the “mature” and retired expats and Greeks more typically found at other organizations)—many are still in their twenties. They are playful, optimistic, and overwhelmingly positive, not to mention tireless, putting in twelve-hour days and using their savings to pay for the privilege and pleasure of helping others in a land foreign to both.

One of the tasks undertaken by the young volunteers is driving the battered but capacious former Skipchen van down to the old airport at Elliniko, on the south coast of the city, to pick up supplies from the main warehouse there. Twice a week they collect dry foodstuffs and other essentials for Khora but also for some of the squats that don’t have their own means of transport. One morning I decided to join them, tipped off by a Bosnian volunteer who’d been a refugee herself during the siege of Sarajevo.

Though there are hundreds of refugees housed in Elliniko, there’s no trace of them as the van enters the derelict site, either outside the former terminal or even peering through a window. We are headed for the closed Olympic stadium nearby, the venue for the basketball games at the 2004 Athens Olympics. For the past two years the stadium has been operating as a sort of clearinghouse for all the goods that are sent to Greece for refugees, from tents and blankets to toothpaste, disposable diapers, food, clothes, toys, and even the occasional frilly party dress.

Jointly administered by the Ministry of the Interior and Pampeiraiki, a private initiative that began in Piraeus when goods started arriving in response to the flood of refugees, the storage area inside the stadium is immense. We walk through canyons of cardboard boxes that reach almost to the ceiling. A chilly place, with bare white walls, ceilings, and floors, it has none of the decorative touches that make Khora so welcoming. Any palpable cheer comes, instead, from the volunteers, who may be working at the tedious task of sorting endless amounts of children’s socks or men’s shoes or winter jackets or any of the other mountains of supplies gathered indiscriminately in this mammoth warehouse.

Negia Milian, the dynamo who runs this show, says, “You have to open every box to make sure the contents match the label, because that is not always the case.”

Another former refugee, Negia left Cuba at eleven and with the help of a Catholic charity made it to Florida. The motherly former head of technology at Citibank met her Greek husband while the two were graduate students at MIT. It’s obvious that Negia’s mind must run better than a computer because she keeps track of everything that enters the warehouse with no apparent effort at all.

Switching between English, Greek, and Spanish, she keeps her unusual mix of volunteers busy. Apart from the four from Khora, there are another four or five young women from Spain, and a handful of older Greek men. The girls push palettes loaded with boxes of pasta, pulses, rice, and tomato sauce as if they are driving bumper cars, frolicking and skipping as if they were kids.

The Spanish connection is strong. Negia tells us the Spanish were among the first to respond to the crisis, both with supplies and volunteers. “They still remember how many countries came to their rescue during the Civil War, when even Syria took in children from the Basque country and Catalonia, which were especially badly bombed. Most of our food comes from Spain,” she says, showing us a series of open boxes, “though other countries contribute generously. Here, for example, is the last of a large shipment of baked beans sent from Ireland. But the main organization we work with, SOS Refugiados Spain, sends us people as well as supplies, and they always tell prospective volunteers to come to this warehouse first, before they go to the islands.”

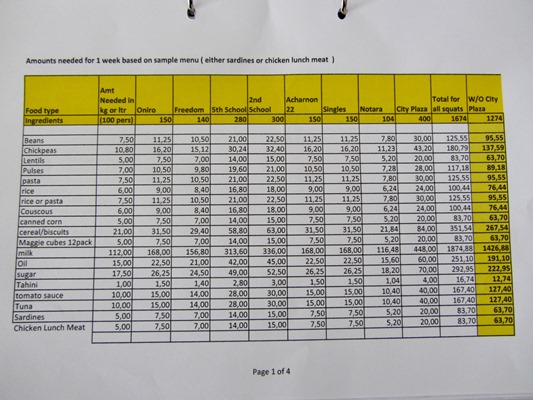

It’s not an exciting place to begin, but it is essential. Negia has printed out a spreadsheet showing the food requirements for nine squats in Athens, excluding Khora, based on a sample week’s menu that she devised using staples to meet basic nutritional needs. There are 1,674 people on the list; the amounts of food (divided between nineteen different products, like “powdered milk,” “chickpeas,” “tahini,” and “sardines”) are staggering—all calculated to the last gram or milliliter, from 180.79 kg of chickpeas to 1,874.88 liters of milk and 83.70 kg of sardines per week. The total number of people fed every week from Pamperaiki’s supplies comes to about 2,500.

Negia’s spreadsheet at the Elliniko warehouse

Negia and Giorgos, a white-haired former ship’s engineer awaiting his pension, started out working at Piraeus. As retirees, both were looking for something meaningful to fill their days. Negia smiles, saying, “I made the mistake of turning up here two days after the warehouse opened here and told the chief coordinator, Sotiris Alexopoulos, that I had some free time. And I never left, have been here ever since.” As for Giorgos, he confesses that he “had never felt such a strong bond with anyone as with these refugees. How could you abandon them? We gave them as much support as we could.”

Meanwhile, the Spanish girls and the volunteers from Khora have started to load the van, lifting and passing heavy cartons as if they contained feathers. They slip dividers between orders for the different squats, pushing them into the back of the van. By the time they are finished, even some of the passenger seats are filled and I find myself having to take the tram back into town.

The very next day, and about a month after I started my research, I received a last-minute invitation to join the International Women’s Day celebration at an organization with yet another formula for helping refugees. Melissa, located in an elegant townhouse near Victoria Square, is a unique network of women helping women. Established migrants from countries as diverse as Nigeria, the Philippines, Russia, and Albania got together with a Greek social anthropologist, Nadina Christopoulou, to create a space where today’s refugees can learn languages, skills, and the confidence to survive and even thrive in their new and unfamiliar surroundings.

Melissa on International Women’s Day

“Melissa” is the Greek word for “bee,” and this former mansion is the hive where immigrant and refugee women, as dedicated and industrious as bees, can share their talents in a fusion of the old and experienced with the new and determined.

Melissa first came to the public’s attention in 2014, when migrant women started cooking for refugees camped in Pedio tou Areos, a big park not far from Victoria Square. One of them, Maria Obilebo, a professional pastry chef from Nigeria who’s been in Athens for almost thirty years, used to make breakfast for the children there. Now, in a culinary feat of almost Herculean proportions, she prepares lunch for 150 women and kids five days a week in her own home and brings it to Melissa, with the help of her sous chef and compatriot, Felicia Anosilce.

For Women’s Day, though, she’s fried up a big batch of crispy, spicy chicken wings, since other women have also brought their specialties to the celebration. I arrive as the table is being laden with platters and bowls of pilafs, noodles, lentils, spring rolls, salads, and much more. An Iranian plate arranged in pretty stripes of different colored rice and pulses receives the loudest roar of approval and everyone, young and old alike, crowds round the table, snapping pictures of the feast with their phones, every face glowing with anticipation and excitement.

Food is so much more than nourishment. Each dish on the table represents a culture and society—civilization on the grand scale, but also a family tradition, a sense of personal identity, and individual creativity and achievement. In some cases these ineffable things may be the only tie a refugee has with home. The late Domna Samiou, a Greek folk music expert and performer—herself the daughter of refugees from Asia Minor—once told me, “When the Greeks left Asia Minor [in 1922], many could not take any possessions with them. All they had was their recipes and their music but that was enough to make a new start.”

When we sat down to a meal with the Afghan women in their container home, we felt their pride at being able to receive us with warmth and offer us their traditional hospitality. At Khora, I saw the camaraderie that comes from cooking and eating together, from sharing tasks and from making oneself useful. At Melissa I felt honored to be present at such a celebration of diversity and of the power and potential of women.

But there is no question that much more help must be forthcoming. Since engaging with refugees and volunteers this winter, I have been following the worsening conditions in Greece and elsewhere on sites like AreYouSyrious and Refugees Deeply. In early April, I came upon a report by a Khora volunteer, Emma Musty, on the situation on the Greek islands in March. She concludes that, “The only moments of hope on this journey have been meeting people involved in grass-root projects where refugee, local and international communities have come together to create alternative solutions, and the strength of the people who continue to endure in this situation.”

The refugees I met with—the ones in the squats and at some of the better-run camps like Oinofyta and Ritsona—represent a fraction of the 60,000 or more people who were stranded in Greece when the borders were shut. What will it take for them all to find a place where they too can cook and share a dish, where they can feel welcome and welcome others?

If the hard-hearted who raise walls to keep refugees out of their backyard could only experience the love and tastes I was treated to, I have little doubt they’d bring down the barriers and let them in.

People who eat together cannot hate.

© 2017 by Diana Farr Louis. By arrangement with the author. All rights reserved.