On a cool spring night in Ramallah a young woman stands alone in front of a microphone, the audience listening to her intently. In a dramatic monologue at once ironic, funny, and desperately sad, she transforms herself into Mariam, living in an apartment block in Gaza. Trying impossibly to prepare for the unpredictable terror of Israeli airstrikes, Mariam runs in circles mentally, physically, and emotionally, desperate to somehow be ready for the destruction that could come, the bombs that might fall on her building at any time. With poignant detail and dark humor she expresses the depths of psychological trauma that she and the people of Gaza have lived with for decades. Her voice alternates between panic, determination, irritation and affection for her elderly mother, and love for her young son. It becomes laced with irony as she catalogs all the ways in which her life is circumscribed, from restricted movement in and out of Gaza, to the outsider voices and NGOs who advocate, offer essential help, or express solidarity in ways, she reflects, that mean “even your freedom is not your own.”

* * *

Khawla Ibraheem’s rehearsed reading of her new play, A Knock on the Roof, was the opening event of 2023’s Palestine Festival of Literature. Each spring, PalFest invites a small group of international writers, filmmakers, and publishing professionals to visit the occupied West Bank. From Ramallah to Jerusalem, Hebron to Haifa and Bethlehem, they meet Palestinian and other writers, poets, activists and educators who share the ways in which Palestinians have for generations forged modes of cultural resistance against the daily trauma inflicted by Israeli state violence on their lives. Over a week my brief experience of the physical and psychological assault that militarized checkpoints and constant covert surveillance inflict was mitigated by the shared stories, generosity, and kindness of our Palestinian hosts, Ibraheem’s powerful statement stayed with me. I was acutely aware that Gaza remained closed, as it has been to external visitors for over a decade. The experience underscored what I already knew about the dearth of work by Palestinian women published and performed in English and the West. It foregrounded imperatives any of us might feel about the writer as witness and ally, or questions we might have about the point of making art and culture through decades of structural oppression and violence, or indeed as genocides both slow and accelerated take place before our eyes. The voice of Mariam, a young woman doing her best to save her mother and child echoed with the right to be heard on her own terms as a daughter, a mother, a woman in Palestine and in Gaza. Since that evening last May, Mariam’s imperatives have only become more urgent.

Khawla Ibraheem at a podium reading from A Knock on the Roof during the 2023 Palestine Festival of Literature. Photo by Rob Stothard of PalFest 2023 on Flickr.

A Knock on the Roof belongs to a broader grouping of contemporary works by Palestinian women who place familial relationships and the domestic at the center of their accounts of Palestinian life. Their choices demonstrate a model of feminist artistic resistance to the Israeli occupation, which as these works show must be understood both by the infinite and overt ways in which the occupation organizes to break families apart, destroy culture, language and historical memory; and by the way they foreground the new families women form in light of such devastating ruptures.

Nowhere does Ibraheem’s statement on freedom resonate more than in the work of writer, activist, and trainee-lawyer Ahed Tamimi. Raised in the village of Nabi Saleh, near Ramallah, she had long participated in weekly non-violent demonstrations against the illegal Israeli settlement that blocked off access to her community’s water spring. The world became aware of her when a clip of her slapping an armed Israeli soldier near her home went viral. Tamimi was just sixteen: she was arrested and incarcerated in Israel’s Harsharon prison for eight months. She spent her seventeenth birthday there.

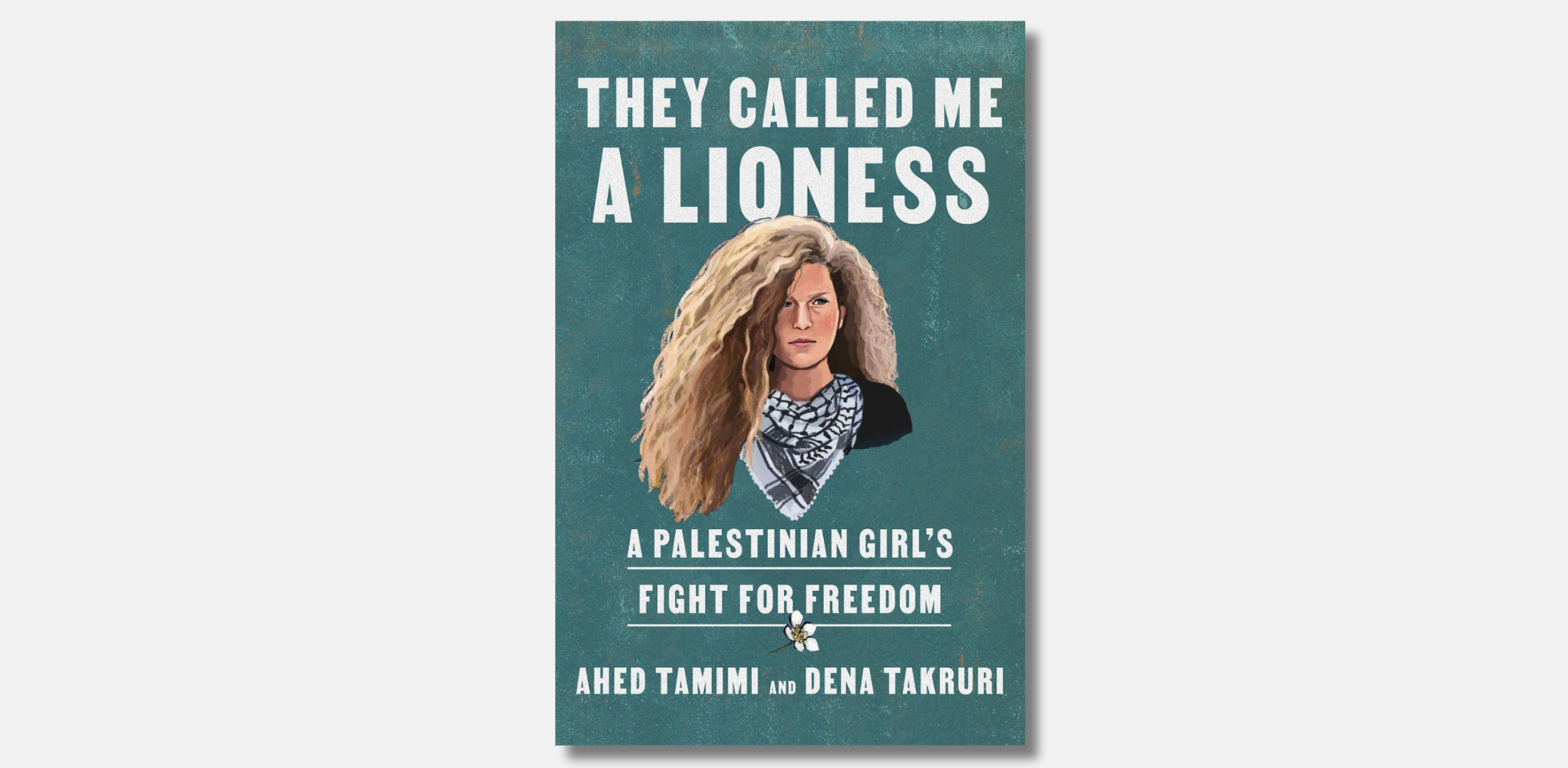

Her recently published memoir, They Called Me a Lioness: A Palestinian Girl’s Fight for Freedom, was written with journalist Dena Takruri and is the winner of a 2023 Palestine Book Award. Takruri, a highly experienced journalist, has a faultless grasp of how to tell a complex story through a personal lens, and of what makes a compelling narrative structure. The book draws the reader through Tamimi’s life via a carefully referenced history of the Israeli settler-occupation of Nabi Saleh, state violence, international law, broken treaties, and current discriminatory policies. Constructed through in-depth interviews with Tamimi, the story is told in the first person, presenting Tamimi speaking directly to the reader. The book lucidly documents her time in prison, rooting it within the context, history, and Palestinian family life of Nabi Saleh since 1967, the year Tamimi’s father was born and the Israeli occupation began.

experience of Tamimi’s formative years.”

One of the book’s great stylistic achievements is that Tamimi’s voice, at once vulnerable, formidable, and determined, resonates beyond the functions of memoir or reader-entertainment to become a powerfully intimate call for Palestinian freedom. This is underscored by the structure of the book, which uses flashbacks written in the present tense, emphasizing the immediacy of trauma repeated across time. The book opens with an image of Tamimi experiencing her arrest as a falling into the past. Shocked and crying in a cell after her arrest at sixteen, she is gripped by a memory of herself as a five-year-old, “sobbing in the middle of the night”: Israeli soldiers have once again broken into the family home while everyone is asleep. She says,

I see my mother falling on the concrete road after being shot by a soldier in a jeep; my younger brother pinned to the ground by another soldier, who is squeezing his little neck in a choke hold; my favorite uncle bleeding to death on the rocks behind our home.

From this time-looped beginning, the chapters take us back further into historical detail and then forward through Tamimi’s childhood: the protest marches she finally joined, Israel’s violent incursions and military raids on the homes, including hers, in and around Nabi Saleh, resulting in the killings of beloved family members. As we read, we carry the knowledge that this militarized violence is the daily experience of Tamimi’s formative years, and as she documents, the stakes are incredibly high for young Palestinian women. There are the relentless, invasive checkpoint strip-searches, there is the constant threat of sexual violence. The cyclical nature of such trauma is counterbalanced in the book through the writers’ formal decisions on its looping temporal structure, which builds a sense of resistance and gives the book a grave authority and political urgency. In the final third of the book, time loops again as we meet Tamimi in that moment at sixteen and go with her into prison.

It is rare to find prison memoirs by young women political prisoners, particularly those written so soon after release. The book sits within a tradition of women’s prison writing that includes the collection A Party for Thaera (2021) edited by Iraqi author and activist Haifa Zangana, translated by Salam Darwazah Mir (and published by Women Unlimited, an associate of the Indian-based feminist publisher, Kali for Women). Here, nine Palestinian women who have experienced Israeli jail tell their stories beyond trauma and sentencing, focusing on details recalled sometimes years after their incarceration.

Palestinian writer and activist Aisha Odeh took thirty-two years to write about the decade she spent inside and has spoken about how traumatic the act of writing those memories was for her even after so many years had passed. Part one of her award-winning memoir Dreams of Freedom (2004) was translated into English by Salma Ayyash. I believe that it has not yet been published; and that part two, The Price of the Sun (2012) has not yet been translated.

In its voice and approach, They Called Me A Lioness is in conversation with these works, and with the writing of Nawaal El Sadaawi, the Egyptian feminist and author whose classic Memoirs from the Women’s Prison (1986) translated by Marilyn Booth is written as a direct address and works as a manifesto for women’s freedoms. Both Sadaawi and Tamimi’s recounting begins with a knock on the door, an arrest, soldiers exploding into their homes. At the time Sadaawi was already well known for her activism and books (she reportedly wrote her text during her incarceration, on pieces of toilet paper with a smuggled eyebrow pencil[1]). She was jailed by the Sadat regime when she was fifty years old. Her book would be published five years later.

Palestinian writer Ahed Tamimi speaks about her memoir, They Called Me a Lioness, at Palfest 2023. Tamimi’s account of coming of age in an Israeli prison won a 2023 Palestine Book Award. Photo by Preti Taneja.

Tamimi is now twenty-two; the timing of her book speaks to her courage and determination to document, so soon after those events, her coming of age in the terrifying conditions of Israeli prison, and to advocate for those still incarcerated. Writing across languages in a partnership that clearly took a huge amount of trust (Takruri conducted many hours of interviews in Palestinian Arabic with Tamimi and translates her words into English for the page), Takruri’s clear and candid prose serves Tamimi’s story well. Unadorned details express the reality of Palestinian women’s lives in Israeli jails, bringing readers face to face with the profoundly well-honed violence of a system that the government never wants us to see inside. We read of the half-hourly flashlight headcounts at night that deny the women uninterrupted sleep. The cramped conditions, stinking cells, and the withholding of sanitary items by the authorities that are part of psychological punishment tactics and an assault on female dignity. Just as important is the ingenuity, care, and survival between incarcerated women, which, like her predecessors, Tamimi emphasizes. On her first night in prison, she watches as her cellmates enact their nightly ritual of sleeping on the floor together in the absence of enough beds; they don’t want any among them to go through the ordeal alone:

It was also my induction to the unique and priceless sisterhood forged within the confines of a cell, where you cannot escape one another and where you grow close in a way that no relationship outside can rival. It’s a sisterhood that would leave an indelible imprint on my heart.

Real female ancestral connections and intergenerational activism are also important here: They Called Me A Lioness is dedicated to Tamimi’s grandmother. For a time, her mother, Nariman, an activist in her own right who initially filmed Ahed slapping the soldier and uploaded the video to Facebook, was incarcerated in a cell opposite hers. The book reveals the agony of a daughter forced to see her mother in handcuffs. “I’ve never experienced a greater pain than seeing her so utterly disempowered,” Tamimi writes. “It was similar to the pain I felt the year she spent unable to walk or care for herself after Israeli soldiers shot her in the leg—only this time, I felt responsible, and my guilt only compounded the pain.”

Nariman becomes a surrogate mother to the young women in prison, simultaneously taking care not to hug Tamimi too often: they don’t want to upset the other girls. Meanwhile Tamimi studies for her school exams and takes lessons in national and international law from experienced women activists she meets inside. She is determined to be released and fulfil her ambitions to advocate for the rights of Palestinians incarcerated under the occupation. According to the NGO Defence for Children International-Palestine (DCIP), before October 2023, “each year approximately 500–700 Palestinian children, some as young as twelve years old, are detained and prosecuted in the Israeli military court system. The most common charge is stone throwing.”[2]

Book cover of They Called Me a Lioness: A Palestinian Girl’s Fight for Freedom by Ahed Tamimi and Bena Takruri

At heart Tamimi and Takruri’s book offers a response to Ibraheem’s statement—“even your freedom is not your own”—by contextualizing Tamimi’s determination to be an advocate for Palestine including via a collaborative act of literary creation. It demonstrates a form of collective female resistance against gendered structural violence made through writing itself.

* * *

Finding similar strength in their own form of women’s shared literary activism, London-based abolitionist publishers Brekhna Aftab and Farhaana Arefin, co-founders of the small independent Hajar Press, have recently brought a collection of contemporary Palestinian women’s voices to readers that equally explore the family, trauma, and reconstruction. Their books bring to life the imaginative possibilities of revisioning the past, moving forward, and return. In Sambac Between Unlikely Skies (2021), also winner of a Palestine Book Award, Gaza-born Heba Hayek employs a series of vignettes in a hybrid memoir in which the narrator “writes of what makes her soul flicker: community love, especially the kind embodied by circles of women and girls.” In this she offers an alternative to the trauma experienced by other Gazan women in America who also grew up “encircled by armies and war machines,” whose stories Hayek travelled across the country to hear, and which she collects in the book. The Sambac tree works as a potent symbol of the form. From Hayek’s narrative branches short chapters hang, their stories alight with humor and shared pain. The writers use techniques including pronoun switches and the present tense to make linkages that resist both the violence of Israel against Gaza, and patriarchal family and social structures. In a fragmentary chapter, “Chronology of a Girlhood in Gaza,” the narrator’s disassociation during abuse, part coping mechanism, part shock, is dealt with deftly: there are the Palestinian “Uncles” with their abusive hands and pinching fingers; a violence repeated in the probing strip searches of Israeli checkpoint guards, “She will push you to the floor and stick her fingers up your ass. Your eyes will feel like someone has stuck lit candles in them, but you will try to stop yourself from crying.”

The writer’s revolutionary choices work even more emphatically when they are deployed to make good on that glimmer of spirit that refuses, at the checkpoint, to cry:

When you get your permit to leave for good, only a few of your family members will show up to say goodbye. None of the men will be there. One of your aunties will tell you that you’re better off learning how to cut onions than getting a master’s degree. You will tell her not to worry, that you’re excellent at cutting onions.

An insistence on the specific detail is at work here, as it is in Objects from April and May (2022), a collection of poems with hand-drawn illustrations by Zena Agha, which she describes as, “a rumination on lost things and the depths to which we can lose ourselves in tracing them.” From the “banal to the beloved,” Agha reminds us that any “thing,” even a girl’s bracelet can be sacred, if we make it so. And that violence can find us anywhere in the world. The victim of an armed robbery in Oakland, California, the attackers took Agha’s necklaces, charms, and pendants. The near-death experience and the loss of precious objects comes to stand for the loss of childhood and homeland: the poems are offered as creative exchange against that loss. They form powerful reconnections across time and country through Agha’s sense of the playful, imperative, mutability of language even as a lost object—its monetary value factual, its emotional power immeasurable—stays fixed to a life in her mind. In “Talisman (2),” which is illustrated with charms on a chain, Agha writes a list poem:

Other items on that chain were:

iv. A dense imitation of the Qur’an. An amorphous hunger pulled me to the window in Al Kadhimiya. $60 and some dinars. (04 -19)

v. A tooth-sized Nefertiti held by a nail-sized safety pin. (14 -19)

vi. A small turtle (21 karat) and a supine hula dancer (9 karat). With the insurance money from the Saab, we fly to Hawaii. Mama will do anything for me. (08 – 19.)

The bracketed numbers suggest Agha’s age at the time she got the charms, and the age she was when they were stolen. At nineteen, a reckoning with the past now comes. It is that sense of physical and psychological assault, of being robbed of objects, a childhood, and of the right to land or to return “home,” and the impossibility of various forms of return except via writing, through which Agha’s poems so delicately work.

* * *

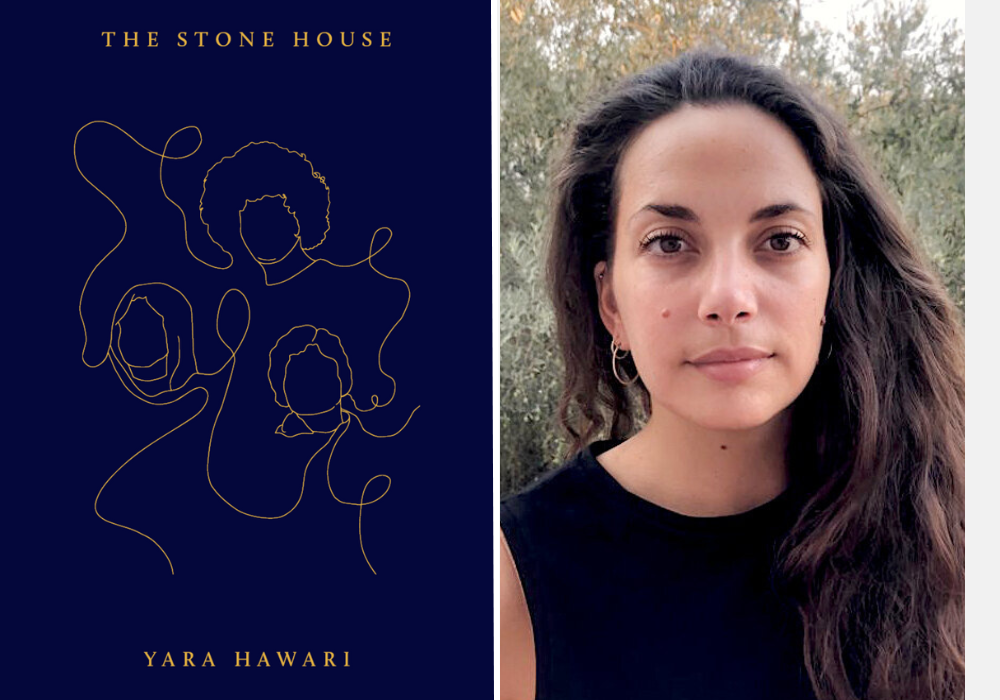

This painfully layered sense of being robbed permeated my experience of travel in the West Bank, as it became clear how deeply the occupation goes into resources and infrastructure, architecture, and landscape. Where Tamimi and Takruri’s book lays out the segregated road system in operation there (which connects Israeli settlements via superhighways that cut through Palestinian villages and can only be used by Israeli cars via a color-coded license plate system), Yara Hawari’s The Stone House (Hajar, 2021), a memoir-as-novel, goes back further, to voice a history in which the very landscape was deployed to mask Israeli settler violence. From 1948, the year of the Nakba, forests of non-native pine trees were planted, spreading rapidly, growing tall, supplanting traditional olive groves and hiding the broken stone houses of Palestinians who were forced by Israel to flee.[3]

The Stone House book cover and writer Yara Hawari

The Stone House re-imagines the lives of Hawari’s own family and those living the 1948 territories to give voice to their “survival against the ashes of the Nakba.” Her experience as a policy advisor shows in the book: she delivers key historical moments in plain language aimed at the non-expert reader. She achieves lyricism by layering these with personal history imbued with emotional truth. Her structure is, like Tamimi and Takruri’s a temporal spiral and so by implication, revolutionary. The book begins with fifteen-year-old Mahmoud enjoying the authority that a seat in the back row of the bus gives him. He’s on his way to the newly occupied territories. From this imagined vantage point, Hawari works backwards into his history and forward into his adulthood, and so is “able to bring the destroyed landscape back to life and blur out the colonizer’s infrastructure.” This is not flashback or simple historical fiction but a shuttling movement of memory against a common Western narrative structure that might choose a starting point, erase a history, and privilege linear progress, and by default is oppressive to colonized peoples. The family house becomes whole and lived-in again and the ancestors—Hawari’s father, grandmother, and great-grandmother—are young once more as the omniscient narrator follows their lives until we meet Mahmoud again, now a man with a wife and a son, and young daughter named Yara. Though Hawari regrets in her introduction that she “did not speak more to [her] grandmother and great-grandmother about the events and intricacies of their daily lives,” she can now recreate young Yara skipping through the forest, a seed pod from the indigenous Carob tree in her pocket, and all the potential to have those conversations still ahead of her.

Hawari takes the reader beyond politics, prison gates, and state violence, and, like the other writers considered here, asks us to think as artists what it means to work within forms that by default tie us into future-forward ways of thinking that can be inherently traumatic. These works offer us truths of Palestinian women’s solidarities and resistance via the joy their authors find and make in the very act of their own expression and creativity.

Their authors’ experiences and imaginings fold into ours through the reading, igniting our empathy. They also challenge us to think about the value, if any, of that emotion beyond the writer-reader compact. These works implicitly—and in Takruri and Tamimi’s case, explicitly—address the question of what real-world solidarity and allyship can be, and about what international publishing, writers, and readers might do. Tamimi writes:

I ask [. . .] that you remember your humanity, because that’s what will decide what you will do when you [ . . .] close this book. Are you going to stand in solidarity with the Palestinian cause and help in whatever way you can—whether by spreading awareness to others, pressuring your government, or further educating yourself about what’s happening? Or will you ignore what you’ve learned, put this book down, and carry on with your life as usual?

* * *

In early June 2023, about two weeks after PalFest ended and I returned to England, Israeli forces raided Tamimi’s village of Nabi Saleh again. They fired on the car of her relative, Haithem Tamimi: his two-year-old son Mohamed was shot in the head. He died from his injuries four days later. At that time he was the twenty-first Palestinian child killed by Israeli forces in 2023. According to the UN Office for Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), 172 Palestinians had been killed in the West Bank and Israel by Israeli forces by mid-August when I completed a first draft of this piece, higher than the total number killed in all of 2022.

Writer Preti Taneja visits the Haram el-Sharif mosque on May 21, 2023 in Jerusalem, Palestine. Photo by Rob Stothard on Flickr.

In September 2023, some PalFest authors and I joined a Zoom call with a group of writers in Gaza, including the co-founder and editor-in-chief of the avant garde online literary journal 28 Magazine[4], Mahmoud al-Shaer. He spoke about the scant access they had to a literary infrastructure of accredited writing workshops, agents, editors, publishing houses, or review culture. Printed books were hard to access then: writers wanting to study contemporary novels made do with partial texts downloaded as PDFs. There was little distribution for new writers outside a few bookshops.

We discussed running a regular online workshop, connecting the Gaza writers with international editors and other ways to get their writing published in the West. Mahmoud had already invited PalFest authors to submit to 28 Magazine: I had started work on a piece before the call and emailed a draft to him on September 29.

October came. What literary infrastructure that existed before Israel’s attacks on Gaza has been, like people’s homes, hospitals, schools, shops and roads, obliterated. Still trapped under a relentless bombing campaign, Gazans now face death by famine, disease, and, because Israel is in control of its water supply, thirst. Mahmoud al-Shaer was out of communication until mid-January of this year when he was finally able to get support and launch an artist GoFundMe, detailing a little of what his family is going through as they try to reach safety in Egypt, a forced exodus that might prove irreversible.[5]

Among the falling bombs and survival imperatives, amid the enormity of the widespread destruction, the devastation of Gaza’s artists and the targeting of its rich artistic life is a deep loss. The obliteration of culture forms part of the definition of genocide and the destruction of books, artworks and structures (which may include publishing houses and universities – all or parts of which have been destroyed in Gaza since October 7[6]) is prohibited under various international conventions and treaties. Palestinian poet Najwan Darwish wrote in January 2024 about the dozens of “writers and journalists who have been killed by the Israelis at this point.”[7] He reminds us we have not just lost poets’ work, but all the work they might go on to write. Ways of seeing and articulation specific to the writing scene of Gaza have been eradicated from the future of Palestinian and world literature. Over 12,300 children in Gaza have been killed by Israel since October as I file this text in mid-February 2024. Generations of lives that will never be lived; stories that will never be written. These books themselves also stand as a material resistance to dangerous, accelerating erasures of home, culture, language, and art. Tamimi’s question—Will you carry on with your life as usual?—forms a clarion call, as urgent artistically as it is morally and politically, a lament and a challenge for all in the literary ecosystem to consider.

Israeli settler violence has also intensified across the occupied West Bank. In early November 2023, Tamimi was arrested again, held without access to her family, and eventually released.[8] The UN reported in December 2023 that over 3,000 Palestinians, including many children, are still being detained and held without charge or trial, in deteriorating and violent conditions, suffering beatings, abuse, “and the threat of rape” at the hands of security forces.[9] That the books I discuss here have found editors, publishers, and distribution at all is incredible given the extreme nature of suppression and struggles detailed by their authors, while in the West, writers as well as people working within literary institutions, publishing, and universities face censorship, loss of funds, or worse for speaking up for Gaza and for Palestinian rights.

* * *

For those of us watching the vast and horrific impact of Israeli bombardment unfold on small mobile phone screens, a sense of futility is difficult to keep at bay. A like, a share can feel meaningless at the best of times; wanting to hold our own governments to account, whether that is writing to an elected representative to demand a ceasefire, or taking part in a march in countries such as the UK where the right to protest is now under threat; writing for social or traditional media outlets, or simply reading might feel similarly futile. But the memory of Mariam, endlessly packing a bag to test what she could feasibly flee with in A Knock on the Roof, stayed with me as I unpacked and repacked in hotels across the occupied West Bank, and when I emptied my suitcase back home. The white, box-like Israeli settler houses stacked in neat terraces on the hillsides of the occupied territory, so reminiscent of the Spanish ghosts of California, now superimpose themselves onto the wildness of the Northumberland hills where I live. The motorways I now drive on feel unstable. The Scots pines, native to this place, take on alien shapes and loom in the dark. My experiences of the violent architecture of full body metal turnstiles, high walls, barbed wire, surveillance, sounds and smells of the UK’s high security prisons, where I taught creative writing for three years to men incarcerated on long and life sentences, segues to the vicious separation walls and checkpoints of East Jerusalem and Hebron, which criminalize by implication all those who are born Palestinian. I am left with a feeling of being lost in a series of interlocking prisons, a maze that some might have the privilege to physically leave, but can never shake off.

I think about why, as a British Asian in Palestine with experience of working with people in Kashmir, in Rwanda, in Northern Ireland, I still so often had the feeling that I could not believe my own eyes. I fell back on what I had read in Tamimi and Takruri’s book, in Hawari’s as a way of saying – yes what I am seeing has been documented; and so that means I am not mad. I felt this dissociation particularly in Hebron. We walked through the old market, its Palestinian shops long shut by military order, its traders forced to set up stall on the cobbled streets. These streets covered in netting to protect people from whatever the Israeli settlers who have occupied the residences above them might throw down, be that dirty nappies, rubbish or stones.[10] I reached Shuhada Street checkpoint and stood beneath the AI-controlled gun that locks on targets remotely and is capable of shooting stun grenades and tear gas and is mounted above the jaws of the turnstile gate.

Shuhada Street checkpoint in Hebron, where the AI-controlled gun locks on targets remotely and is capable of shooting stun grenades and tear gas. Photos by Rob Stothard on Flickr.

I watched as a young Palestinian boy passed under its mouth: he was simply trying to get home from school. I followed him: under the gun, through the metal teeth and the identity check, to the Israeli side, where a bored young soldier, fully armed, went through our international passports again, lingering over the documents of those who were not white. Then down the well-paved sidewalk, lined with stone panels and advertising hoardings inscribed with heroic narratives of the settler story. It was a “through the turnstile” mirage, surely. I searched my mind for taught knowledge about Palestine, the occupation: the British role in all of this. The 1947 British Partition of India tore apart millions and was the defining event of my own family history: it traumatized my grandmother into a silence about her childhood that lasted the rest of life. The full events and losses are only now beginning to be taught in British schools. The British way is to stay as mute as possible, from school curricula to mass media about its part in violence and oppression, at home or in the world. It’s a lacuna into which anyone who grew up in England might comfortably fall, within which anyone might comfortably stay, without any desire or conscious decision to change.

But a stack of compelling and thought-provoking books by Palestinian women now sits on my table. Through variations of form and style that express their unique shared and hybrid histories and multiple world-views, they invite readers to laugh and to mourn with them, to feel love, and want change and to imagine possible futures away from decades of violent and insidious systemic harm. They remind us also that there is solidarity to be expressed in the smallest of actions. In the literary context it might be translating, sharing, publishing, programming, and promoting Palestinian voices in appreciation of the variety, literary excellence, and the political importance of their work.

At the end of Ibraheem’s reading of A Knock On The Roof, the dramatic tension got so intense that my mind shorted out and I missed the denouement: I have no recollection of what happens at the end of the play. Though the terrible evidence from Gaza now fills in the gaps, I still want to believe that Mariam escapes the falling bombs and lives to tell more, and different, stories. And that enough people continue to read, write, march and speak out until all whom she represents can get to safety, and can return home. And that safety and that home, are permanent, equal, their own and free.

___________________________________________________________

[1] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/mar/22/nawal-el-saadawi-obituary

[2] https://www.dci-palestine.org/children_in_israeli_detention. Accessed 2 OCT, 2023

[3] For more on this history see: https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/books/violence-of-planting-in-israel-palestine

[5] https://www.gofundme.com/f/aid-for-mahmouds-family-amidst-gazas-war?utm_campaign=p_lico+share-sheet&utm_medium=copy_link&utm_source=customer

[6] https://theconversation.com/the-war-in-gaza-is-wiping-out-palestines-education-and-knowledge-systems-222055

[7] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/jan/04/najwan-darwish-palestinian-poet-israel-gaza-war

[8] https://www.theguardian.com/world/video/2023/nov/30/freed-activist-ahed-tamimi-speaks-of-plight-of-palestinians-held-in-israeli-prisons-video

[9] https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/un-rights-office-seriously-concerned-about-israels-increased-arrest-palestinians-2023-12-01/

[10] https://palsolidarity.org/2008/01/settlers-rain-stones-and-urine-on-palestinian-home-and-street/

© 2024 Preti Taneja. By arrangement with the author. All rights reserved.