One of my fondest memories of Dubravka Ugrešic (who passed away on Friday, March 17, 2023, at the age of seventy-four) is a postcard she sent me.

At the time, I had just met her—virtually—and was working on Thank You for Not Reading, my introduction to her world. A world in which literature matters, but authors from small countries or languages are overlooked (especially if they’re female), whereas their editors earn the big bucks and fly business class while putting their authors in coach. Her world in which the New York Times bestseller list is nothing more than contemporary Socialist Realism, providing a set of dictates that determine what will be popular and what won’t. (See: Paulo Coelho versus any and everyone capable of writing real literature.) A world in which it’s easier to become a literary success if you’re a soccer player first. Or an Ivana Trump. (The Kardashian nature of cultural success hasn’t changed a bit in the ensuing decades.) As she pithily points out, it’s way harder to become a famous author and then transition into being a sports star. But vice versa? It’s much easier to envision a cardboard cutout of Lionel Messi in a bookstore pimping the biography he “wrote,” than one of Dubravka, championing Karaoke Culture, one of the most insightful works of cultural criticism to be published this century.

In Dubravka’s creative nonfiction, you can see her mind at work, dissecting the world as is, pointing out absurdities and foibles with a blistering sharpness and sarcasm that was unmatched. There’s a reason she was consistently rumored to be on the Nobel Prize shortlist: no one wrote like her, no one thought like her, no one was willing to say what she was willing to say. (Which, to be fair, are reasons both why she more than deserved the prize, but also why safer options were selected. The “Witch of Zagreb,” as one prominent Croatian newspaper referred to her, dismantled the bullshit that the literary industrial complex traffics in on the regular. Not good for Nobel business, I suppose.)

One of the most amazing aspects of Dubravka’s essays is how she manages to poke fun at things you, as a reader, might really like—or at least may have never questioned—and/or you yourself (see above jokes about editors, another of which is the obligatory picture of an editor in front of a shelf of books, which, yeah, I deleted that profile pic). And yet, and yet, you’re always on her side. Dubravka’s right. And thank god she shared her wisdom with all the rest of us.

Two decades of working with Dubravka, and she still intimidates me. I can hear her over my shoulder pointing out all that I’m missing or misconstruing. Which is true: it’s easy to point to Dubravka’s most cutting, hilarious works—“Assault on the Minibar,” which I think about every time I travel, comes to mind—instead of engaging with the complex, multifaceted pieces like “Karaoke Culture,” “There’s Nothing Here!,” all of The Culture of Lies, etc. And we haven’t even gotten to her fiction!

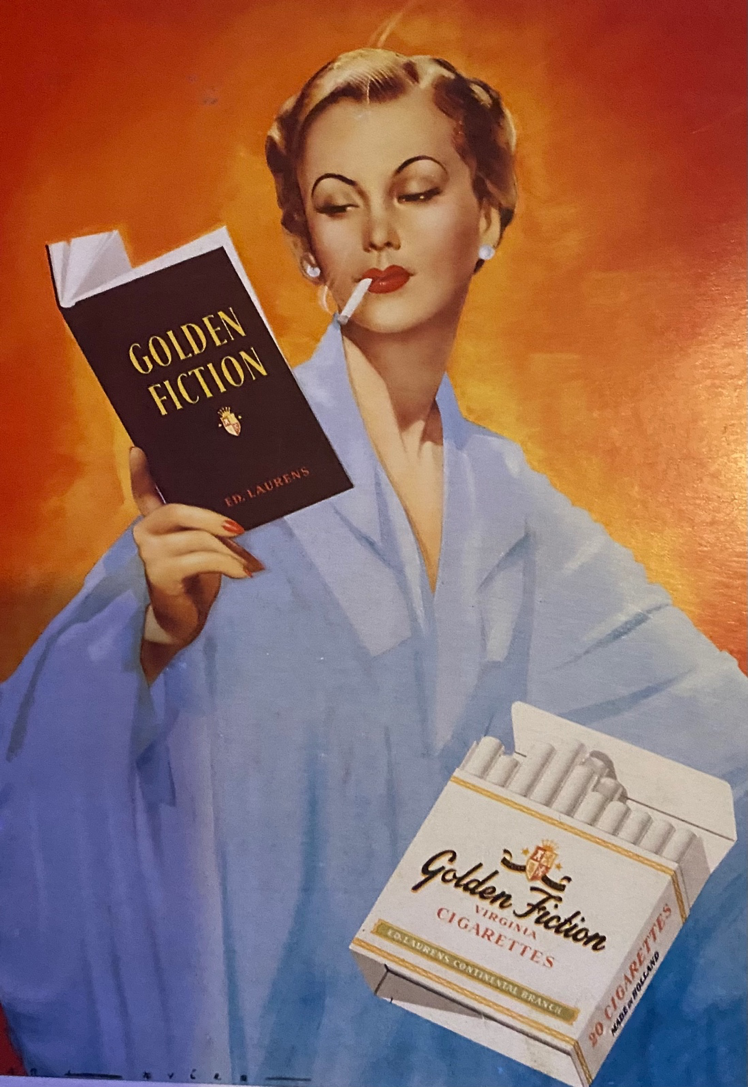

So, back to that postcard she sent me. At the time that I was working on Thank You for Not Reading, I was a rebellious twenty-seven-year-old who was committed to smoking cigarettes and hating the establishment. All of the references in Dubravka’s early works to the depiction of smokers in contemporary media—as the villains, frequently dressed in black, not to be trusted because SMOKERS—hit home. I mean, just look at the title of the book. Equating reading with smoking—a verboten activity, one that the powers that be don’t approve of, that disrupts the status quo in a personal way—is such a Dubravka move.

Once upon a time, we were going to do an event at McNally Jackson Books on Prince Street in New York City. Before the event we met at the restaurant on the corner nearby to have a glass of wine, catch up, prep for the event. It was springtime; we were sitting outside, right against the makeshift fence designating the outside world from the official restaurant space, shooting the shit in our typical, semi-manic, who can be more sarcastic and cynical about the literary world sort of way, and she lit up. Almost immediately, a waitress appeared to tell her she wasn’t allowed to smoke there. “Outside?” “In the restaurant. You have to be on the other side of this barrier.” “But my cigarette is on the other side of the barrier!!!” No matter how hard she tried to explain the weird logic that had taken hold of NYC’s virulent mindset against smoking, she couldn’t win this argument. Smokers are evil. They wear black. They read. And think in ways we’re not supposed to think.

There are so many things I loved about being friends with Dubravka. Sure, I was always scared to call her—I’m not as up on current affairs as I should be, I’ve not read as much as people assume, what if I like the wrong movie?—but as soon as we were together, I felt so much love, so much comfort. For all the writers in the world today, it’s rare to find a true literary traveler. Someone who believes in words and books and publications and the impact of these professions.

Photo by Jen Rickard Blair. From left to right: Ellen Elias-Bursac, Dubravka Ugrešic, and Chad Post

Being with her when she received the Neustadt International Prize for Literature in 2016 was magical. I would go so far as to say that that moment, that series of events—especially the staged production of Life Is a Fairy Tale and the reception with students who had spent a semester reading all of her works—was the last bit of magic the world has been privy to. (Think about it! A week later the Cubs win the World Series, then Trump does the unthinkable, then he does ten more unthinkable things, then COVID, then . . .) Nicknamed the “Little Nobel” given the overlap between shortlisted Neustadt authors and Nobel Prize winners, this award was a resounding testament to Dubravka’s influence on modern letters. The outpouring of admiration for her works, the attendance at all the events, the sheer glory of it all . . . I don’t know that I’ve ever seen Dubravka more sheepishly joyous than I did over those few days. For someone who always wanted the respect and love of the literary world writ large, she was never as cocksure or glory-wallowing as her male counterparts. That was part of her charm.

Introducing Dubravka at the opening reception was the last time I pulled out the postcard I have in front of me right now. A postcard without a stamp—I assume she sent it in an envelope?—and a simple message: “Dear Chad, You would like this one, I guess. Dubravka.”

I have a very distinctive memory that I’m having a hard time tracking down, but want to share anyway. Post-Karaoke Culture—which, I haven’t mentioned yet, but should, was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award for Criticism, a rare occurrence in those days when translations were still ghettoized—we were having lunch and she told me a story about how she was supposed to take a trip for a literary event, but had to fill out a visa request form on a tiny computer at the airport. (Maybe it was the ESTA system to visit the US? I’d like to think it was.) It was set up so you only had ten minutes to complete the entire form. The buttons were very small and, if I remember correctly, you had to use a roller-ball to move the cursor to the right fields. She failed. Asked for help from the check-in agent. Failed again. Went home. Didn’t travel. But, a year or so later, I read a new, updated, less tragic, more funny, politically tinted version of this story in her book. I was a temporary Dubravka sounding board, and I will take that to my grave.

This is the postcard.

Cigarettes. Fiction. A woman with maximally arched eyebrows. And a silent confidence. She smokes. She looks on the self-proclaimed “Golden Fiction” with a bit of distrust. It might entertain, but it doesn’t satisfy. Her robe billows in ways elegant, seductive, dismissive. She’s a fucking badass.

And Dubravka wrote golden fiction. Her words shimmer. The snark, the vibe, the learned references, the structures so smart that her readers can puzzle over her books for decades, the laugh, the way she shook her head and her hair followed, the smirk and the glint in her eyes, the two pairs of glasses she wore around her neck for reading and seeing, the hospitality, the graciousness, the belief, god the belief, I miss her, because she was golden. As was her writing, which will live on forever.

The last time I was supposed to see Dubravka was in March 2020. I was going to be in London for the book fair and a University of Rochester fundraising event. COVID arrived. I went anyway. And even traveled to Amsterdam. But didn’t tell her. (I was very sick and terrified she would ask me over regardless and I would be the one to infect her.) The plan was to go through her archives, which the U of R was interested in preserving. As was I. One of the big themes in Dubravka’s writing was a fear about what happens to an artist’s work—especially a female artist from a small country and language who didn’t win the Nobel Prize and never had a bestseller—after she passes. I’m fortunate enough to be in a position to guarantee that I’ll do everything I can, personally, to be that champion she dreamed of. Who makes sure her works are both available and read in 2123. Who will cultivate her audience between now and the cessation of my time on earth.

© 2023 by Chad W. Post. All rights reserved.