Afonso Henriques de Lima Barreto (1881–1922) was born to a generation that grew up in Brazil with two important words reverberating ideas of equality among the members of society: abolition and republic. On the one hand, the demand for equality between citizens regardless of their origins; on the other hand, the demand for political power to be held by the people through their elected representatives rather than a monarch. As a descendant of Africans, Lima Barreto witnessed these two decisive moments of Brazilian history in 1888 and 1889 while still a child. However, the promise of social reforms emanating from these twin historical turning points did not fulfill the expectations of some writers who emerged in the post-abolition and post-republic context, including Barreto.

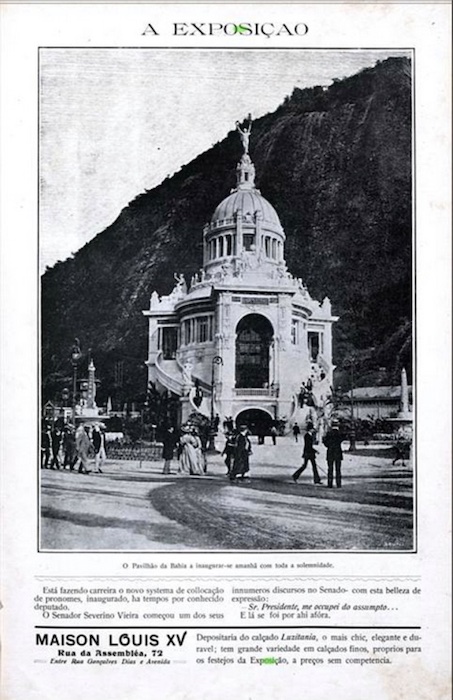

The apparently democratic and progressive ideas of the final years of the nineteenth century, however, eventually paved the way for what has been defined as a tropical belle époque, a period characterized by the blossoming of a new republican elite culture. In literature, this was expressed in the form of frivolous optimism, mannerism, and elitism, sometimes even adopting aspects of pseudoscientific racism. These aspects, of course, dominated what has been conventionally defined as the elite culture of Brazil’s First Republic, encapsulated by the cultural paradigms of the European aristocracy adapted to the new carioca urban life.

Indeed, Barreto was one of the many writers who endeavored to discuss these complex transformations, but perhaps one of the few to openly criticize their racist and aristocratic underpinning. Embedded in his frustration at not witnessing the values of equality of the abolition and the republic put into practice in everyday life, he embarked on a crusade against the new Republic’s establishment figures, focusing his writings on the mechanisms of social differentiation that were practiced at the time, particularly those that aimed at creating an elitist white culture distanced from the “degenerate” masses. According to Barreto himself, the aim of his crusade was to produce a type of literature that he defined as “militante,” engaging with the society’s most pressing issues and communicating these issues to a wider audience in accessible language.

Borrowing from various writers of the second half of the nineteenth century, Barreto absorbed the idea that literary value should not be judged on beauty alone but on a combative language aimed at bringing about real impact on society. He echoed writers such as Tolstoy, who claimed in his essay What is Art? (1897) that the language of a relevant piece of literature for the time had to be “contagious” and aim for the masses, further asserting that “the common people have a right to art.” In his reading of Tolstoy, Barreto emphasized that the tendency to create obscure, elitist works that were inaccessible to the masses should be strongly opposed. For the Russian, “great works of art are only great because they are accessible and comprehensible to everyone.” Barreto emphasized this mission throughout his works and managed to summarize it in Amplius, his 1916 manifesto.

Our duty as sincere and honest writers is to cast aside all the old rules, all the outward strictures of genre [. . .] At its best, this is what the literature of our time has been doing, and may it, through the virtue of its form, no longer seek to replicate the vaunted ideal of beauty of bygone Greece [. . .]; no longer the exaltation of a love that was never at risk; but the communion of men of all races and classes, bringing about mutual understanding between them, in the infinite anguish that defines mankind. [. . .] We no longer desire a disengaged literature. [. . .] That is not what these times require; but rather an activist literature that might contribute to the greater glory of our species.1

Lima Barreto’s intellectual project was largely influenced by the major debates of fin de siècle Europe, which had as its backdrop the emergence of mass society. This new context came out of not only the urban population boom but also the expansion of public education and the consequent rise in literacy rates, as well as the growth in the number of newspapers and magazines and their ever-increasing circulation.

This technological and social revolution of the turn of the century divided intellectual circles, especially in Europe, and the perspectives of writers toward the unprecedented masses participating in the intellectual and public life varied widely. In this battle of the extremes there was, on the one hand, a supposed need for intellectuals to declare war on the masses; this eventually took the form of exclusion of the popular classes from the debate of ideas or even ideas of physical extermination of their ever-growing ranks. At the other extreme were those intellectuals who perceived mass society as a powerful instrument of social change that could be fostered through the written word, particularly through major newspapers and magazines.

Intellectual discomfort in relation to the growing masses gained force in the first decades of the twentieth century with the population boom and the concentration of the masses in the cities, and subsequent overcrowding of public spaces such as trains, parks, hospitals, schools, beaches, and streets. To some, like the philosopher Ortega y Gasset, these masses were invading spheres that were once reserved for the well-heeled, creating a “dictatorship of the masses.” In aesthetic terms, many like him believed that art and modern literature should be markers of distinctions in society, with artists producing something necessarily inaccessible to the masses, whether due to the means by which the works were published or even the language and literary diction they used. Art and literature were for the select few, not for the many.

This perspective had been circulating in various intellectual circles of the late nineteenth century. In his major work on this subject, the critic John Carey points to Nietzsche as one of the most influential voices of the period pushing intellectuals to declare war on the masses and, if necessary, annihilate them. Extreme enthusiasts of such ideas even suggested that these pariahs should be exterminated in enormous gas chambers while watching the images projected by a cinematographer (movies had become a popular form of entertainment in the first decade of the twentieth century).2 Aware of the European debate at the time, Lima Barreto had a very different perspective on the subject and even made radical public objections to Nietzsche’s ideas. His most striking rebuke was published in 1920.

Though my vices are numerous, I do not believe hypocrisy is one of them. / I do not like Nietzsche; I feel a personal antipathy toward him. [. . .] It was he who gave the rapacious bourgeoisie that governs us the philosophy that best expresses their behavior. He has exalted brutality, cynicism, amorality, inhumanity, and, quite possible, duplicity. [ . . .] / It’s hard to imagine how humanity, which can only exist through the society of men, might exist without the very sentiments that strengthen this society and make of it a thing of beauty./ Nietzsche is very much the philosopher of this era of predatory bourgeoisie, lacking as it is in scruples of any kind; [the philosopher] of this era of brutality, of hardness of heat, of this make-money by all means possible, from the bankers and businessmen who do not hesitate to reduce thousands to poverty, to wage wars, all to make a few million more.3

Lima Barreto’s emphasis on intellectual efforts that could promote harmony among the different rungs of society was a reaction not only to Nietzsche but also to the influential interpretations that combined the ideas of the German philosopher with the postulations of eugenics. This combination aimed to formulate new moral codes to combat a supposed racial, intellectual, and social degeneration. These theories were based on the idea that human capacity was generated not by education but inherited (Hereditary Genius is the title of Francis Galton’s influential book, first published in 1869). This, in turn, would only prevent degeneration if “racial purity” were cultivated, maintaining supposedly “intrinsic racial hierarchies.” In other words: according to this narrow reading of the time, the Übermenschen of Nietzsche would be the result of the elimination of miscegenation.

Theories based on eugenics were spreading quickly at the turn of the century. In the first decade of the twentieth century, one could already find various eugenics education societies in many countries. These institutions sought to give public visibility to studies on heredity and their arbitrary racial hierarchies, supporting efforts to guide public policy that argued for supposed biological improvements in societies. Their members included several influential intellectuals who publicized these ideas in their writings in the first half of the century, such as the German physician Alfred Ploetz (1860–1940), who coined the term “racial hygiene,” and John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946), the renowned British economist who was an active proponent of eugenics and became director of the British Eugenics Society in the late 1930s.

Lima Barreto perceived the vileness of these doctrines very early on in his career, clearly positioning himself as a writer opposed to the dissemination of such ideas in Brazil. This reaction is a characteristic of his work and helps to understand the humanist vocabulary used throughout his works. In a long, powerful entry from his journal in 1905—when he was just starting to write his first pieces for periodicals—he makes his point with extraordinary clarity:

There is, throughout the globe, the increasingly common notion that some races are superior and others are inferior, and that this inferiority, far from temporary, is eternal and intrinsic to the very structure of those races. / It is also said that any mixture between these races constitute a social ill, a plague, and all other sort of ugly things. / All this is affirmed in the name of science and in accord with the authority of those wise Germans. / It’s unclear to me whether someone has already observed that German has increasingly taken on, in this our lucid age, the prestige once reserved for Latin in the Middle Ages. / Whatever is said in German constitutes transcendental truth. For example, were I to say in German that a square has four sides, this would be received as something extraordinary, despite the fact that in our lowly Portuguese this is but a banal near-truth. / And thus this whole thing gains new legs, thanks to the weak critical faculties of those concerned, and more than this weakness, to the intellectual cowardice that we possess in the face of important European figures. It is imperative we see the danger of these ideas, both for our personal happiness and to our mankind’s position of superiority. Currently, such ideas have yet to emerge from the offices of politicians or from the laboratories, but tomorrow they will spread far and wide, they’ll be at the disposal of politicians, they shall fall upon the heads of the uneducated masses, and we may well have to endure killings, humiliating separations, and our most liberal era will find its new Jews. [. . .] Today, it is cause for joy that I am able to say such things, to address these august institutions without feigned restraint. It is my soul’s satisfaction to be able to offer rebuttals, to aim my sarcasm at the arrogance of such judgments, which have caused me suffering since the age of fourteen.4

More selectively, but no less drastically, eugenics was one of the many ways in which intellectuals reacted to the rise of the masses at the turn of the century. And it is evident that Lima Barreto conceived his project of a “literatura militante” as a weapon to fight against the absurdities of that moment, when many intellectuals dreamed of extermination or the sterilization of the masses, sometimes suggesting that many could not be considered human beings.

Another debate related to the intelligentsia’s reaction to the growing masses revolved around the expansion of public education implemented across several countries during this period. Many have even suggested that the masses should not be literate at all, and that only intellectuals should dominate the sphere of written culture. Nietzsche himself argued that education should remain a privilege and be selective, being offered only to those most equipped to produce great and lasting works. For him, education for the masses should not be the goal of any society.5 While some explicitly argued that the masses should have purely physical lives and activities and should not learn to read and write, others rejected the liberal idea that the masses could be educated. Some went as far as stating that there was statistical evidence that crime increased with the spread of education and that schooling turned members of lower classes into menaces to society.

Much of this debate was related to public policies in several countries that expanded access to education during that period. It would take several decades before the ambition of universal literacy, which emerged among Europe’s Illuminist philosophers, was put into practice. And it was only in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries that literacy rates began to grow and approach universality in industrialized countries, coinciding with a demographic explosion that marked the beginning of mass popular culture. At the beginning of the twentieth century, adult literacy rates in some European countries reached above ninety percent. This expansion was one of the principal changes marking the turn of the century. This unprecedented huge literate public eventually revolutionized various aspects of the production and dissemination of print culture, particularly that of newspapers and magazines.

It is at this historical moment, for example, that popular, large-circulation publications started to gain more space, seeking to win over this emerging audience. This is a period of transformation in the structure of the press, with newspapers and magazines becoming sources of profit and taking on the form of large commercial structures. With growing print runs and advertisements on their pages, these publications sought to provide their audience with attractive, accessible content in a constant effort to maximize their readerships.

Many European intellectuals did not look kindly upon the growth of popular newspapers and magazines. Their reactions were marked by hostility. One of the elements of this reaction against commercial publications and their mass audience was the drive to obfuscate the spheres of the written word. Some, like Aldous Huxley, regarded this lack of simplicity in literature as the first attempts of writers to be consciously literary in a period that witnessed the beginnings of mass popular culture, leading to a reaction of the most elaborate artificiality characterized by a language as remote as possible from that of ordinary life. Decades later, critics such as John Carey saw this tendency for obfuscation in the early twentieth century as a literary mechanism to separate intellectuals from the masses. According to him, certain writers would deliberately produce texts not aimed at less initiated audiences and readers, championing those with the capacity to make their work accessible only to a few.

Many writers, however, openly embraced this new audience, who largely lived in the suburbs of large cities of the Atlantic world. In The Suburbans, a famous book on the subject published in 1905, the British writer Thomas Crosland shows how a new literary diction was created in these popular publications, defining what he called “a suburban talk.” He saw this colloquial style of the white-collar suburb in authors who explicitly explored literary approaches that dialogued with the masses. This suburban diction became a concern for traditional intellectuals, in part because it trivialized “serious” subjects with colloquial, irreverent, and playful language, avoiding complex artifice and bringing literary texts closer to the language of ordinary life.

In Brazil, particularly in the capital of Rio de Janeiro, Lima Barreto was one writer who chose to deliberately foster new approaches to the literary language of his time, and he did so on two main fronts: on the one hand, he put in practice his “literatura militante” in books and literary magazines published in Brazil, which usually had a very limited and selected readership; and on the other hand, he wrote for various popular magazines with nationwide circulation, reaching an unprecedented audience as a result. This allowed him to put into practice some of the basic pillars of his “literatura militante”: clarity in discourse, wide dissemination of the message, and active engagement with the most pressing social issues of the day.

Although still modest compared to other countries, the growth in the absolute number of citizens able to read in these first decades of the twentieth century was substantial in Brazil, as their number grew from 2.5 million in 1890 to more than 8.7 million in 1920. Spread across various cities, this unprecedented number of readers was precisely one of the main drivers of the expansion of the press in Brazil in the early twentieth century. Among the publications that emerged in this period, one particular type was a pioneer in appealing to this new readership that previously had little access to the written culture: the weekly popular illustrated magazines.

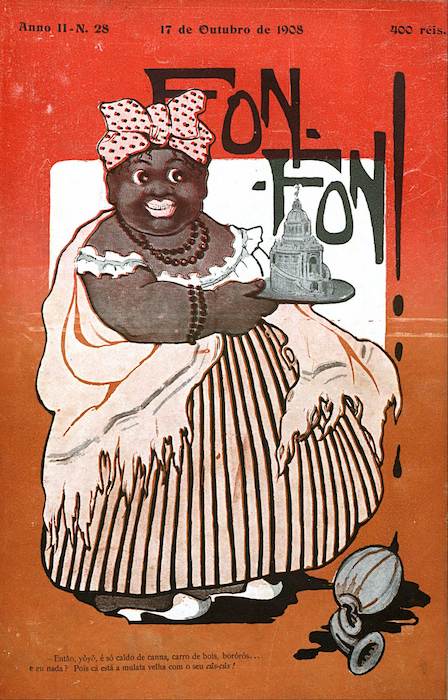

Although illustrated magazines had been circulating for a long time in Brazil, publications such as O Malho, Fon-Fon, Revista da Semana, and Careta began to achieve new record-breaking levels of circulation. Like many others of their type in the Western world, these magazines were all founded in the first decade of the twentieth century and meant to become the defining publications of their period and pioneers of mass media in Brazil. Their popularity derived not only from their political cartoons, photographs, and humor pieces, but also from their nationwide circulation (in contrast to daily newspapers, which were largely local). In fact, most of their readers were not in the capital, Rio de Janeiro, but spread across the country. These were not small-circulation literary magazines. Their fundamental role was to deliver contents and goods (advertisements were a fundamental feature of these publications) from the capital to other distant parts of the country by train or cargo ship.

In 1919, Monteiro Lobato suggested that readers of these popular magazines were mostly lower-middle class workers, such as train drivers, porters, waiters, and white-collar workers who had received basic education and lived in suburbs and small towns spread across the country. For him, these popular magazines attracted this mass readership thanks to their humorous, simple articles, and through their caricatures and captions that employed a more conversational and ordinary language, in striking contrast to the literary language of academic writers such as the prolific Coelho Neto, a founding member of the Brazilian Academy of Letters famous for a prose style full of linguistic virtuosity, extravagant vocabulary, and a grammatical approach more attuned to European Portuguese. However, it was precisely this appeal to a mass readership that meant these publications enjoyed less esteem among intellectuals and writers, who tended to galvanize around more select literary publications.

By writing for the press, particularly for large-circulation magazines, Lima Barreto combined popular appeal and intellectual sophistication in search of his “literatura militante.” His Tolstoyan project of writing for readers of all kinds is everywhere expressed in his reaction against the distinction between high and popular culture, theory and empiricism, fiction and journalism, and his way of combining a deep literary knowledge with his own personal experiences in Rio at the turn of the century. By placing himself in between these opposing categories, Barreto was waging battle on at least two fronts. First, he criticized elitism and mannerism among writers who sought classical beauty in dissonance with the radical transformations and debates that characterized Brazilian society at the time. Nonetheless, he did not identify with popular culture to the extent of calling himself a representative member of the lower classes. By rejecting both positions, Barreto could produce works that functioned as an intersection between the Brazilian intelligentsia and the emerging masses, particularly their literate members. It was from this standpoint that he spoke throughout his career as a writer.

His critique of elitist and inaccessible uses of literary language was intimately linked to his perspective in the debate on the role of literature in an unprecedented moment of intense expansion of mass communications. For him, literature served a social function as a powerful weapon to fight social fragmentation (racism and classism) in post-abolition Brazil. These were the two biggest targets. While this has long been clear through his aforementioned collaborations with popular magazines, the impact gained new dimensions with the discovery of 164 unpublished pieces, mostly signed with pseudonyms. These discoveries were made public in my Sátiras e outras subversões (Penguin-Companhia das Letras, 2016), in which I explain how digital technologies made it possible to find such a high number of new texts by an author whose “complete” works were already established.

These discoveries, as well as the recent biography Lima Barreto: triste visionário (Companhia das Letras, 2017), by Lilia Moritz Schwarcz, have opened new avenues with regards to the life and works of this Afro-Brazilian crusader. While the biography gives a much more nuanced understanding of the racial issues that Barreto faced in that period, with detailed chapters on the racial challenges faced by his parents and grandparents prior to the abolition of slavery in Brazil and the impact on Barreto’s childhood, the recently discovered texts shed light on the extension of the engagement of the writer with the popular press. Although these collaborations with magazines had been frequently downplayed, with scholars emphasizing his novels, these new works have shown that on the one hand Barreto’s literary crusade was mostly fighting against racism and elitism, and on the other hand, how this mordant Afro-Brazilian writer made use of the popular press as one of his main weapons in the public debate during those years of the First Republic in Brazil.

Works Cited

Barreto, Afonso Henriques de Lima. “Amplius” A Época 10 Sep. 1916. Hemeroteca Digital Brasileira. 15 Jul. 2017. http://memoria.bn.br.

Carey, John. The Intellectuals and The Masses: Pride and Prejudice Among the Literary Intelligentsia, 1880–1939. London: Faber & Faber, 1992.

Correa, Felipe Botelho. Lima Barreto. Sátiras e outras subversões: textos inéditos. São Paulo: Penguin-Companhia, 2016.

Crosland, Thomas. The Suburbans. London: J. Long, 1905.

Gasset, José Ortega y. La Rebelión de las masas. Madrid: Revista de occidente, 1930.

Huxley, Aldous. “Euphues Redivivus.” In On the Margin. London: Chatto & Windus, 1923.

Lobato, Monteiro. “A caricatura no Brasil.” In Idéias de Jéca Tatu. Obras completas, vol. 4. São Paulo: Brasiliense, 1964.

Needell, Jeffrey. A Tropical Belle Époque: Elite Culture and Society in Turn-of-the-Century Rio de Janeiro. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

Schwarcz, Lilia Moritz. Lima Barreto: triste visionário. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2017.

Tolstoy, Leo. What is Art? New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company, 1904.

1. A Época, Rio de Janeiro, September 10, 1916.↩

2. D. H. Lawrence in a letter to Blanche Jennings apud Carey, John. The Intellectuals and the Masses: Pride and Prejudice among the Literary Intelligentsia, 1880—1939. London: Faber & Faber, 1992, p. 12.↩

3. “Estudos.” Gazeta de Notícias, Rio de Janeiro, August 26 1920, p. 2.↩

4. Diário íntimo. São Paulo: Brasiliense, 1956.↩

5. Nietzsche, Friedrich. Lecture III. In: Anti-education: On the Future of Our Educational Institutions. New York: New York Review Books, 2016.↩

© 2018 by Felipe Botelho Correa. By arrangement with the author. Translations of Lima Barreto © 2018 by Eric M. B. Becker. All rights reserved.