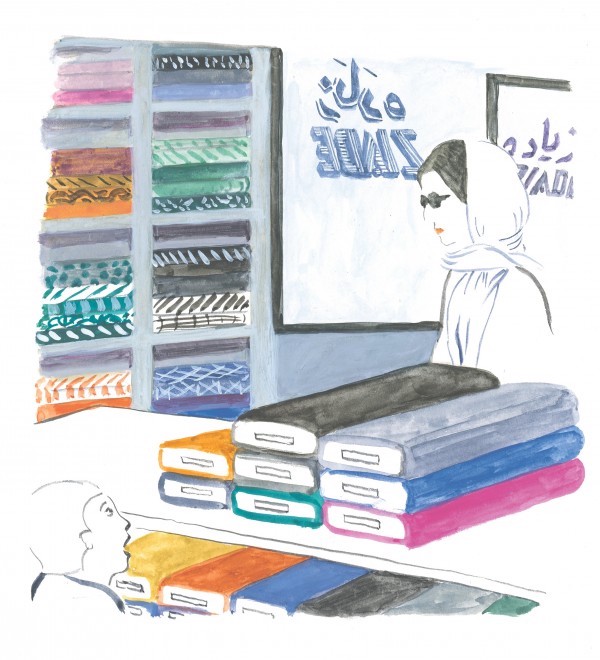

Fairuz represented a new kind of Arab star. In making the Rahbani brothers a household name, she offset with their music the predominance of Egyptian song but conducted herself in a fashion far from common to starlets of her standing. Her songwriter, manager, and, later, husband Assi Rahbani had laid down new rules for the game, and these were at polar odds with longstanding custom. Assi turned down all offers for her to sing at private gatherings. No palaces, no villas, no presidential dwellings. Fairuz was only to sing on stage. Let the high and mighty of the world come to hear her at the theater if they so desired. When the Shah of Iran and Malake Soraya came to Beirut in 1957, supplications from the presidential palace and the Iranian Embassy fell on deaf ears. Assi turned down a request for a private concert in their honor. The same went for Habib Bourguiba in 1965. This was unheard of. The giants of the past had performed all their lives for royalty! Umm Kulthum, Farid al-Atrash . . . Mohammed Abel-Wahhab, who in his younger days was nicknamed “singer to princes and kings.” He had already sung before Faisal’s court in Baghdad as early as the 1920s and by the late 1970s still kept up close ties with Hussein of Jordan and Hassan II of Morocco, his greatest admirers . . . And then there was Asmahan, who had practically only ever sung at private parties! But not Fairuz. Assi’s unyieldingness became a claim to fame. Not content simply to turn down private concerts, he also made it his code of conduct never to write paeans to any leaders. But Umm Kulthum and Abd el-Wahhab had sung in praise of the young Farouk I. And they now lent themselves to the glories of Nasser. So be it, but not Fairuz. Not the Rahbanis. It was a matter of principle. And it was a principle dictated by moral comportment on Assi’s part that no one questioned, certainly not Fairuz. Fairuz, whose fame was the plague of her life. Pathologically shy, she took no advantage of her renown, loathed the celebritariat, wanted to act as if nothing had changed. One day she walked into my grandfather’s shop on Souk al-Tawileh, the main street of Beirut’s commercial heart. I was there. It was the early ‘70s. Though I have only patchy memories of the time, since I was only five, that blessed spring day is forever graven in my memory. She was with her sister. She had on a scarf over her head, tied under her chin, and a raincoat. Sunglasses she’d taken off as soon as she came inside. Her face was as familiar to me as a neighbor’s down the street, but I didn’t recognize her at first, despite the silence that in a matter of seconds had swallowed the shop whole. Nor did the whispers and agitation from the employees and customers tip me off. It really wasn’t until I heard the miraculous words “Ahlan wa Sahlan Sitt Fairuz, kif halik?” from my grandfather’s mouth—Welcome, Madame Fairuz, how are you?—that I took a good long look at this woman, unremarkable yet bathed in an inexplicable aura, that it suddenly dawned on me. Identifying the idol I’d only ever seen on TV terrified me immediately, I who was also pathologically shy. And when she spoke the words “Kifak inta Khawaja” in reply—And yourself, Monsieur Antoine?—to the formal pleasantry with which my grandfather had welcomed her, I was petrified. For I had just recognized her voice.

“Fayrouz dans le magazin de mon grand-père,” from Ô Nuit Ô Mes Yeux. © 2015 by P.O.L. Editeur. By arrangement with the publisher. Translation © 2018 by Edward Gauvin. All rights reserved.