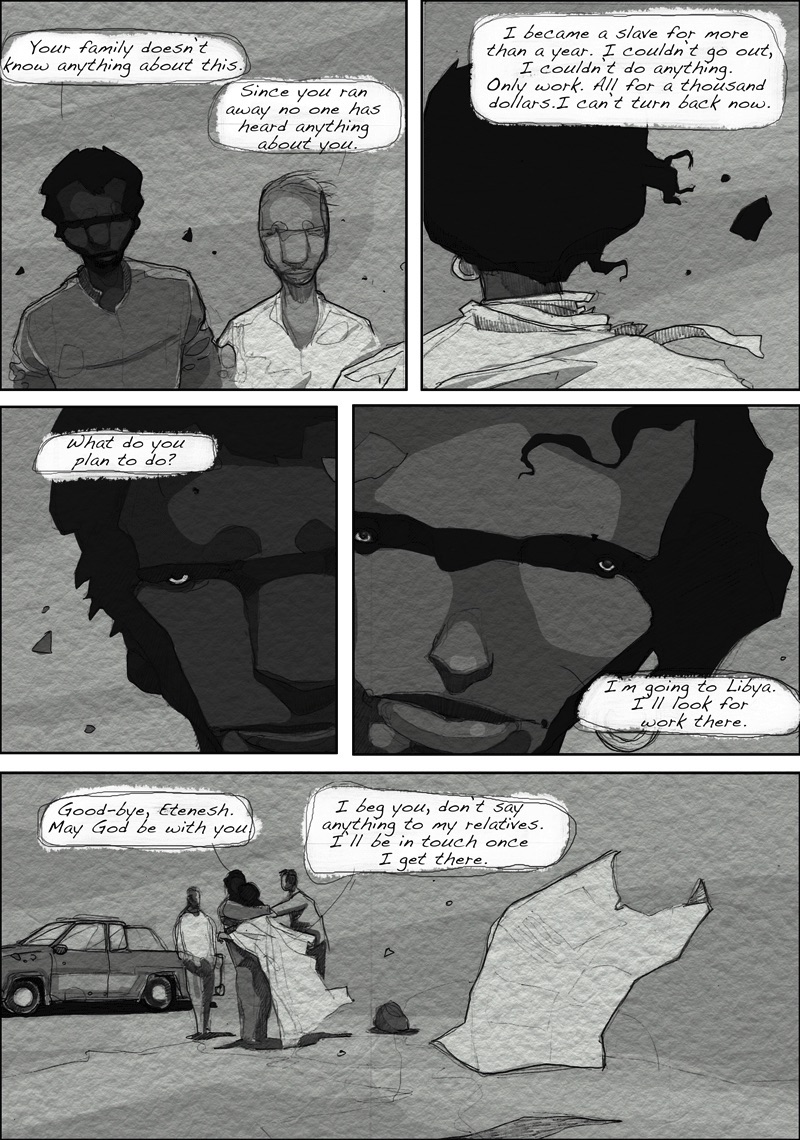

“Your family doesn’t know anything about this.”

“Since you ran away no one has heard anything about you.”

“I became a slave for more than a year. I couldn’t go out, I couldn’t do anything. Only work. All for a thousand dollars. I can’t turn back now.”

“What do you plan to do?”

“I’m going to Libya. I’ll look for work there.”

“Good-bye, Etenesh. May God be with you.”

“I beg you, don’t say anything to my relatives. I’ll be in touch once I get there.”

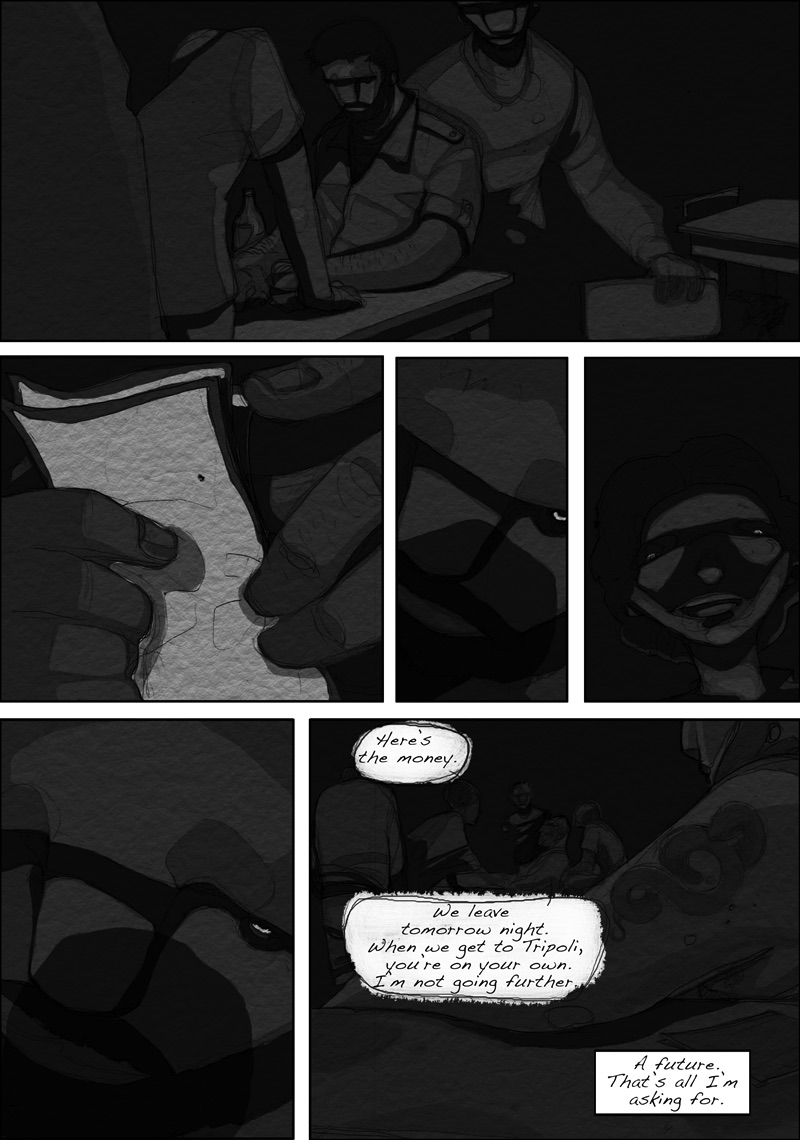

“Here’s the money.”

“We leave tomorrow night. When we get to Tripoli, you’re on your own. I’m not going further.”

A future. That’s all I’m asking for.

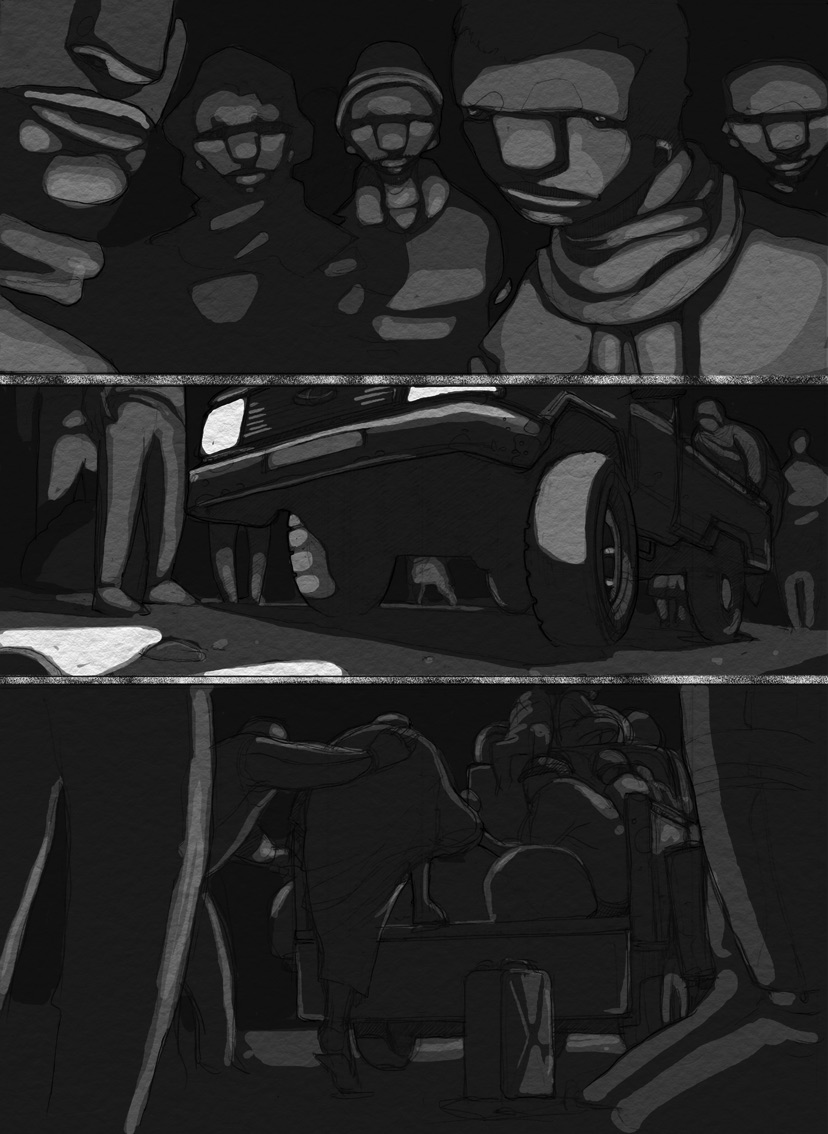

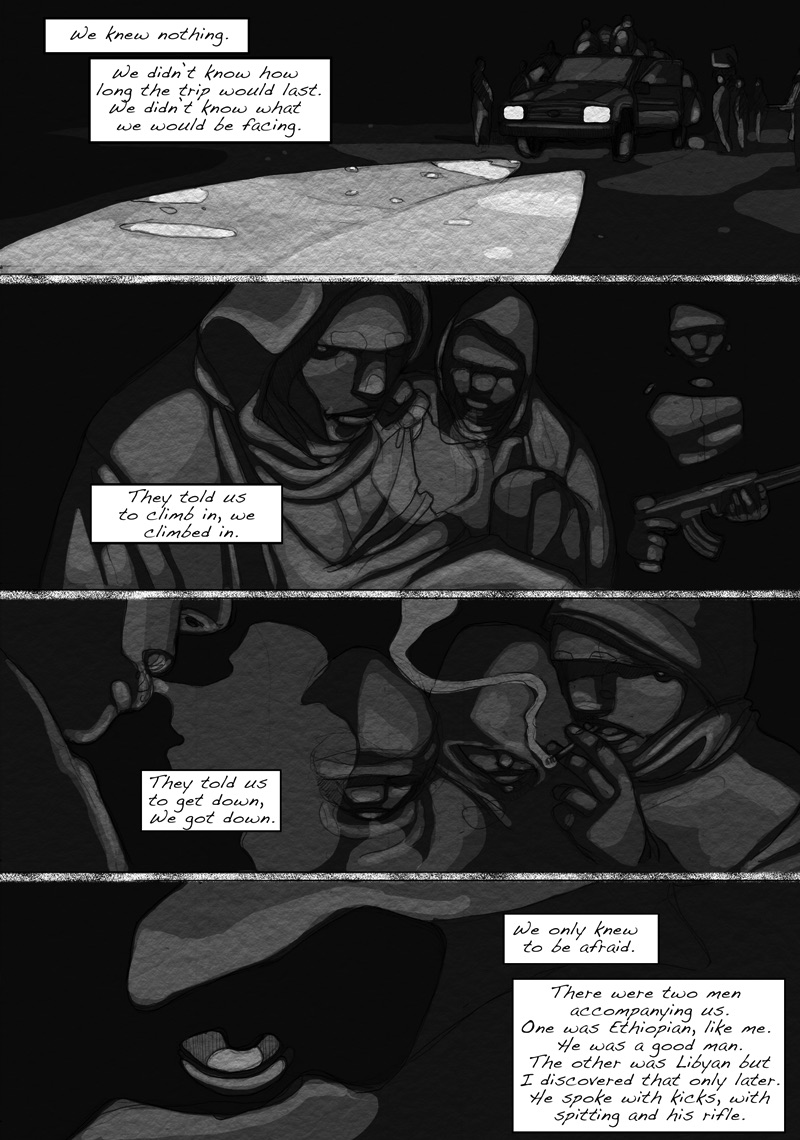

We knew nothing.

We didn’t know how long the trip would last. We didn’t know what we would be facing.

They told us to climb in, we climbed in.

They told us to get down, we got down.

We only knew to be afraid.

There were two men accompanying us. One was Ethiopian, like me. He was a good man. The other was Libyan but I discovered that only later. He spoke with kicks, with spitting and his rifle.

The Sahara doesn’t give you time to get used to it.

Already, the first day of the trip was hell.

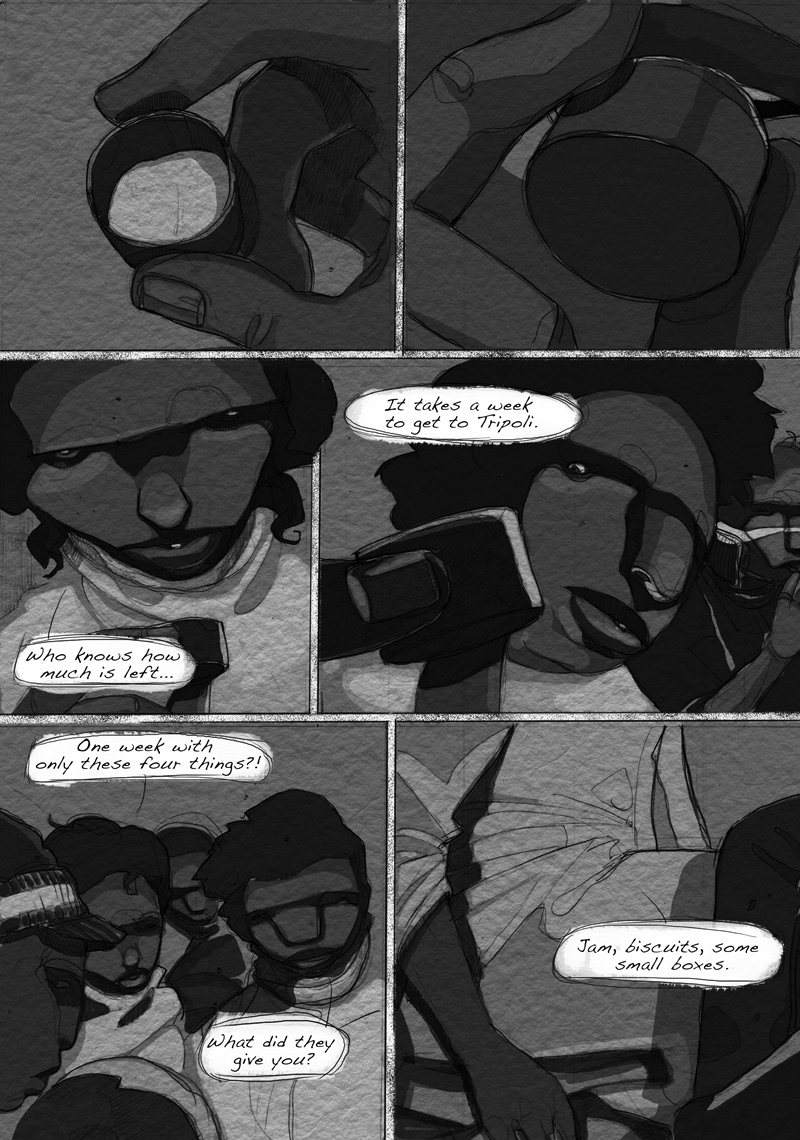

“Who knows how much is left . . .”

“It takes a week to get to Tripoli.”

“One week with only these four things?!”

“What did they give you?”

“Jam, biscuits, some small boxes.”

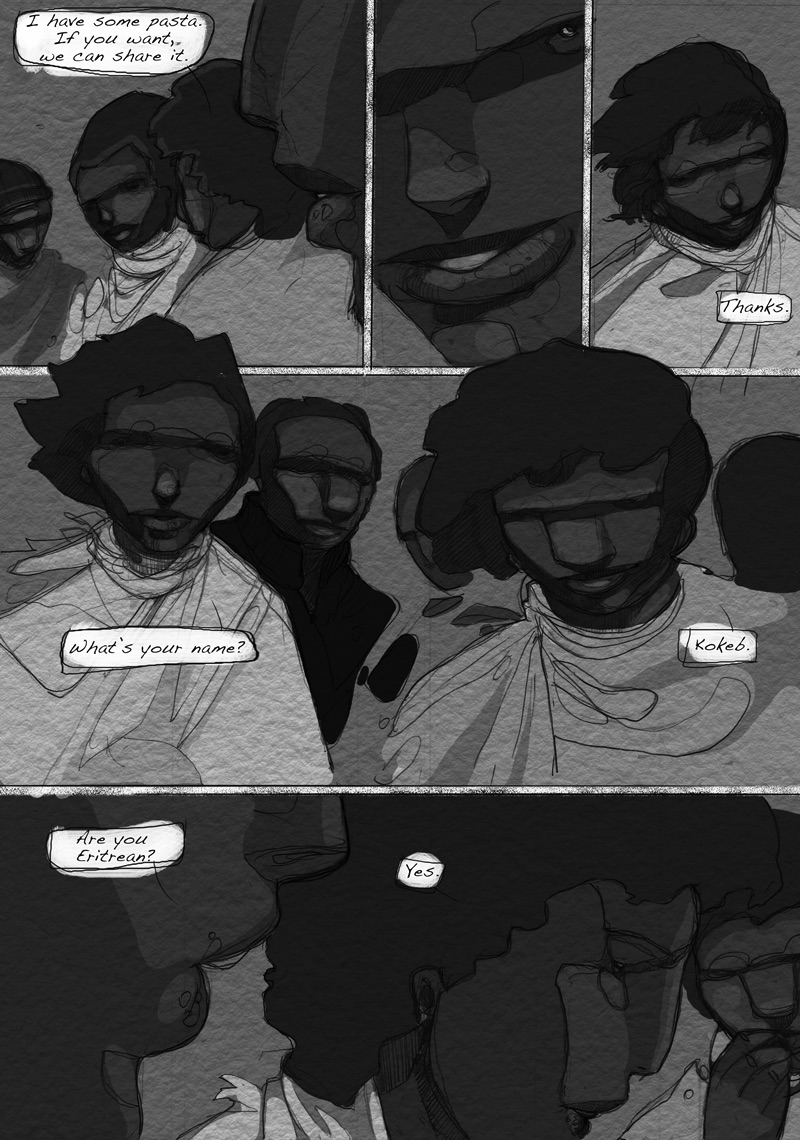

“I have some pasta. If you want, we can share it.”

“Thanks.”

“What’s your name?”

“Kokeb.”

“Are you Eritrean?”

“Yes.”

“A month ago they attacked my village. They killed a lot of people.”

“My father and mother died. My brother was taken away.”

“He’ll become a soldier.”

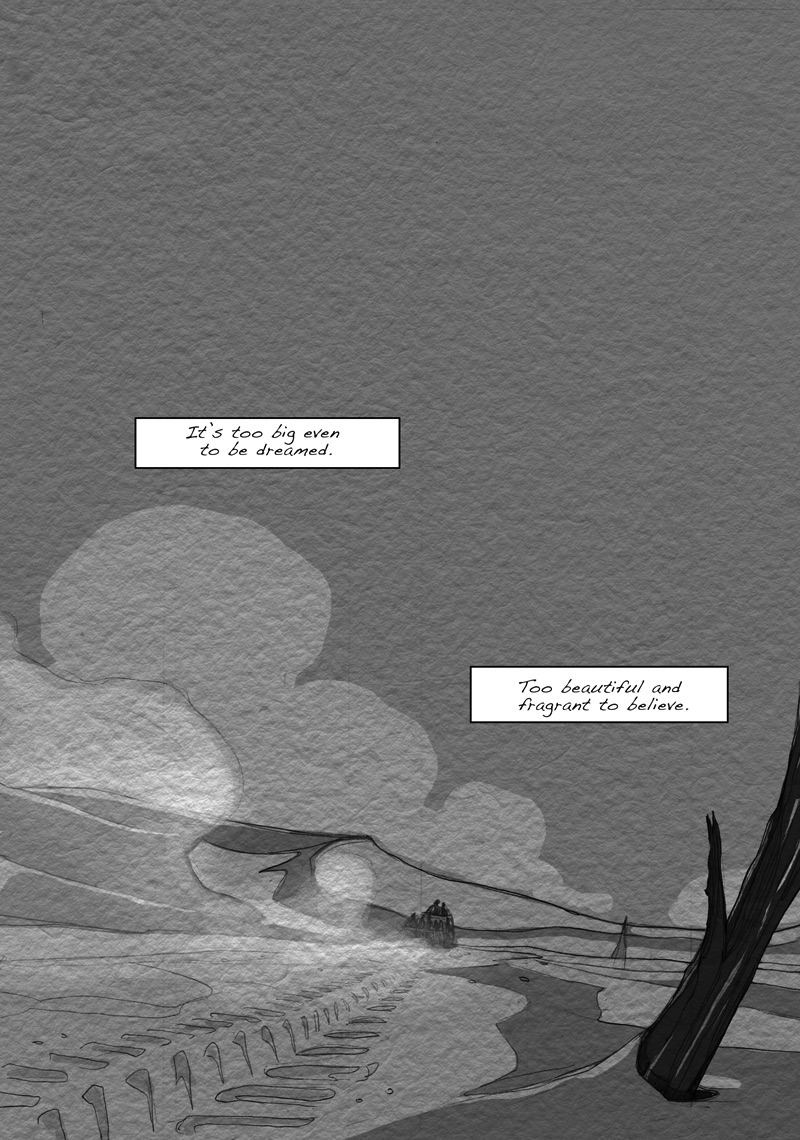

The sand cuts your face and mixes with your tears.

The desert, the first time that you see it, stuns you into silence.

It’s too big even to be dreamed.

Too beautiful and fragrant to believe.

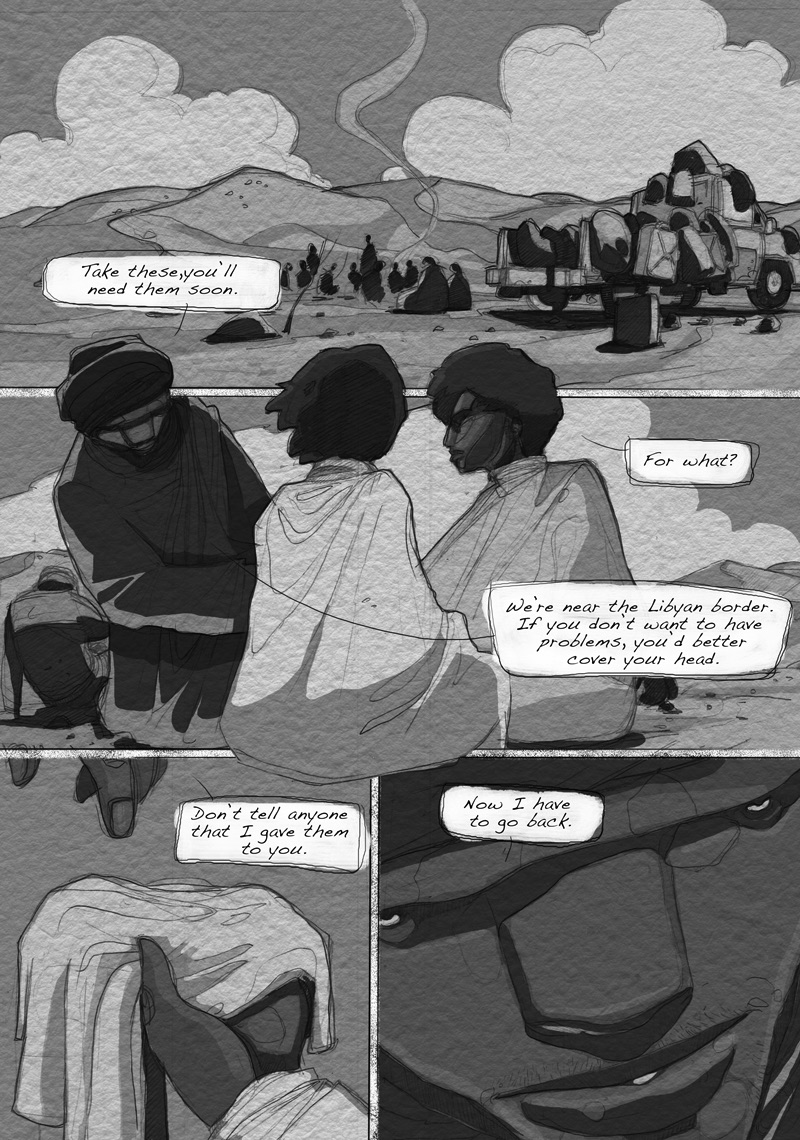

“Take these, you’ll need them soon.”

“For what?”

“We’re near the Libyan border. If you don’t want to have problems, you’d better cover your head.”

“Don’t tell anyone that I gave them to you.”

“Now I have to go back.”

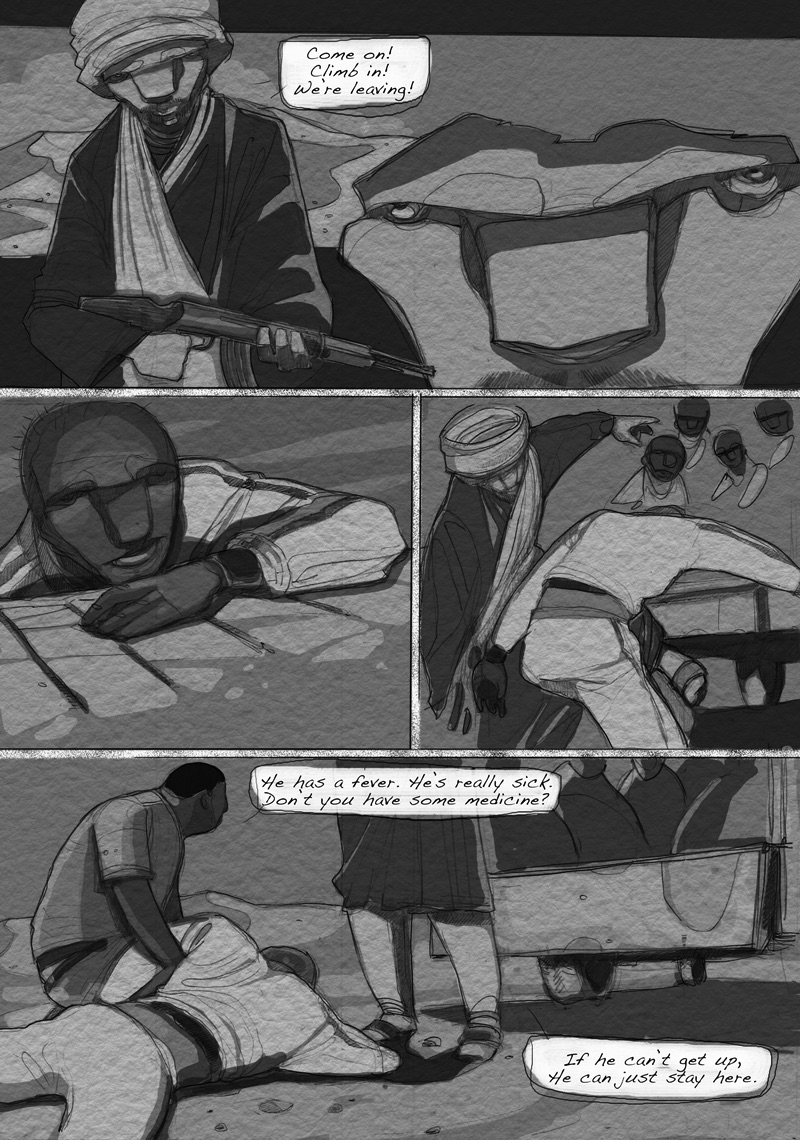

“Come on! Climb in! We’re leaving!”

“He has a fever. He’s really sick. Don’t you have some medicine?”

“If he can’t get up, he can just stay here.”

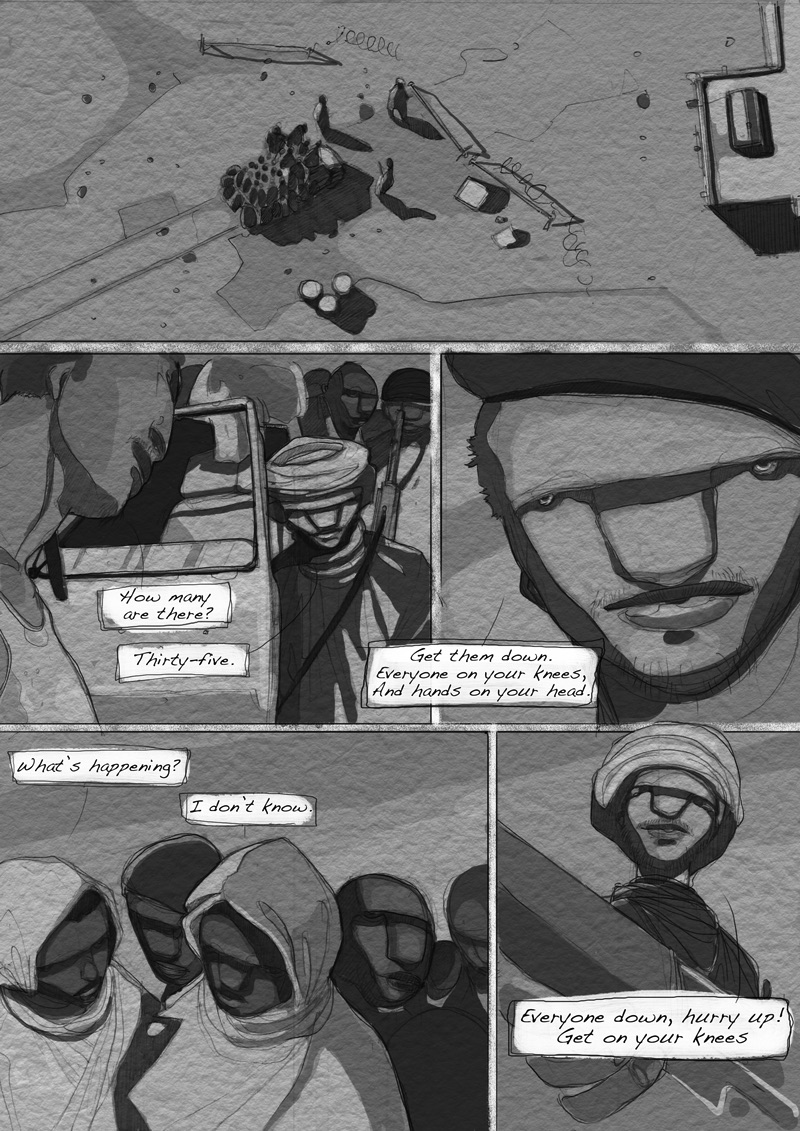

“How many are there?”

“Thirty-five.”

“Get them down. Everyone on your knees, and hands on your head.”

“What’s happening?”

“I don’t know.”

“Everyone down, hurry up! Get on your knees”

“Kneel. Move it.”

“Get busy. Check all the bags well.”

“Asshole, leave that stuff alone!”

“? . . .”

“I saw people forced by the military to drink fetid water in order to induce intestinal problems and make them expel wads of banknotes rolled up in cellophane that they had swallowed so they wouldn’t get stolen.”

“I saw 44 of the 50 travel companions that we left with die. We had been in the desert for two and a half weeks without water or food. The two Sudanese truck drivers had abandoned us in the desert. They said to wait, that two other trucks would come to continue the trip. But they didn’t come for over two weeks.”

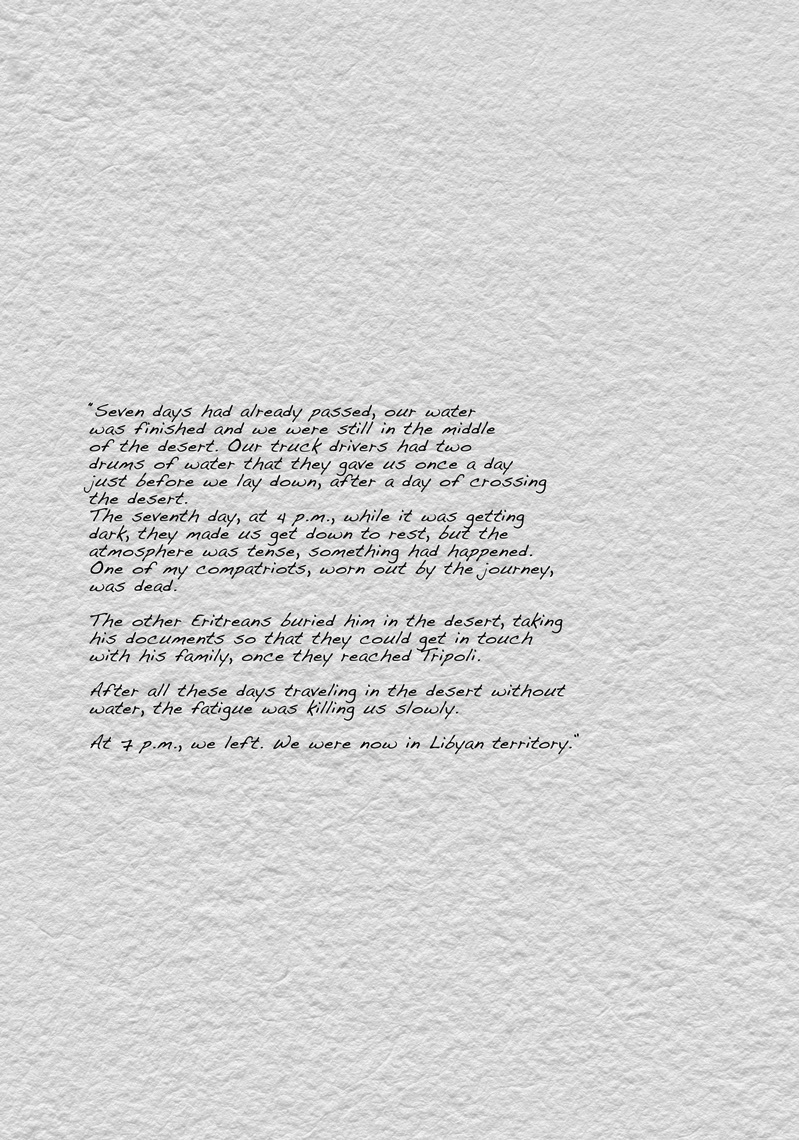

“Seven days had already passed, our water was finished and we were still in the middle of the desert. Our truck drivers had two drums of water that they gave us once a day just before we lay down, after a day of crossing the desert. The seventh day, at 4 p.m., while it was getting dark, they made us get down to rest, but the atmosphere was tense, something had happened. One of my compatriots, worn out by the journey, was dead.

The other Eritreans buried him in the desert, taking his documents so that they could get in touch with his family, once they reached Tripoli.

After all these days traveling in the desert without water, the fatigue was killing us slowly.

At 7 p.m., we left. We were now in Libyan territory.”

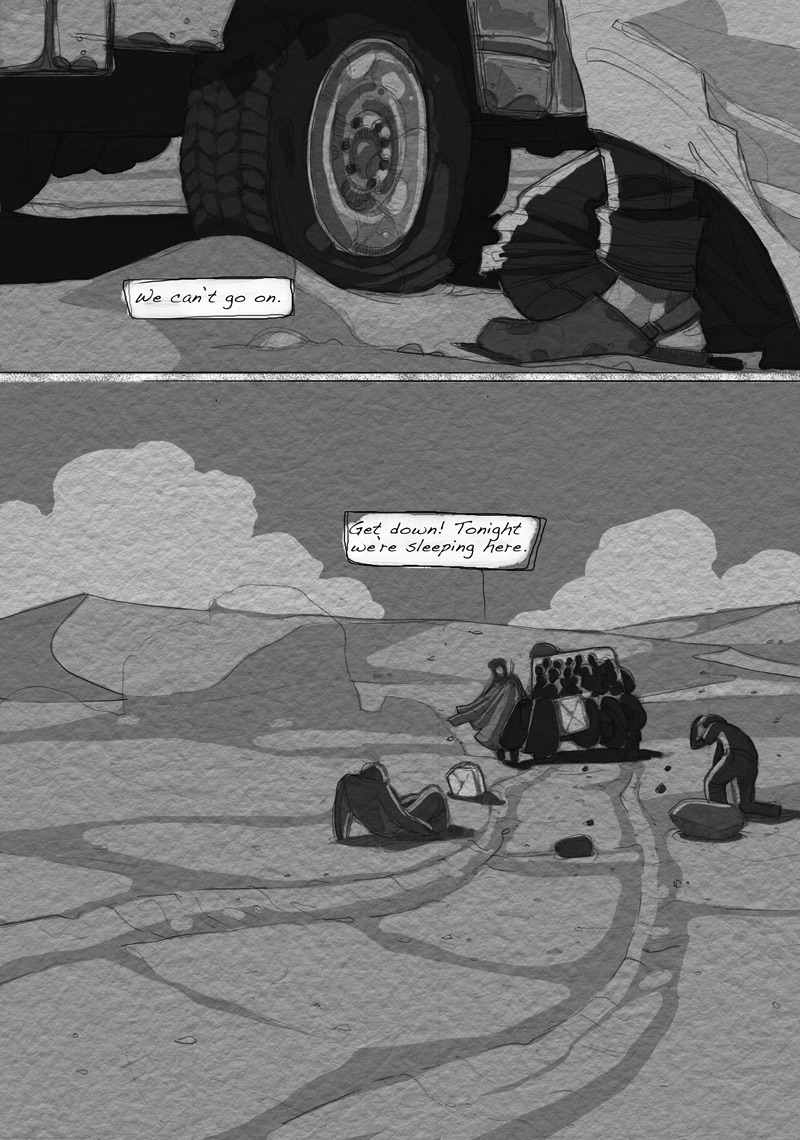

“We can’t go on.”

“Get down! Tonight we’re sleeping here.”

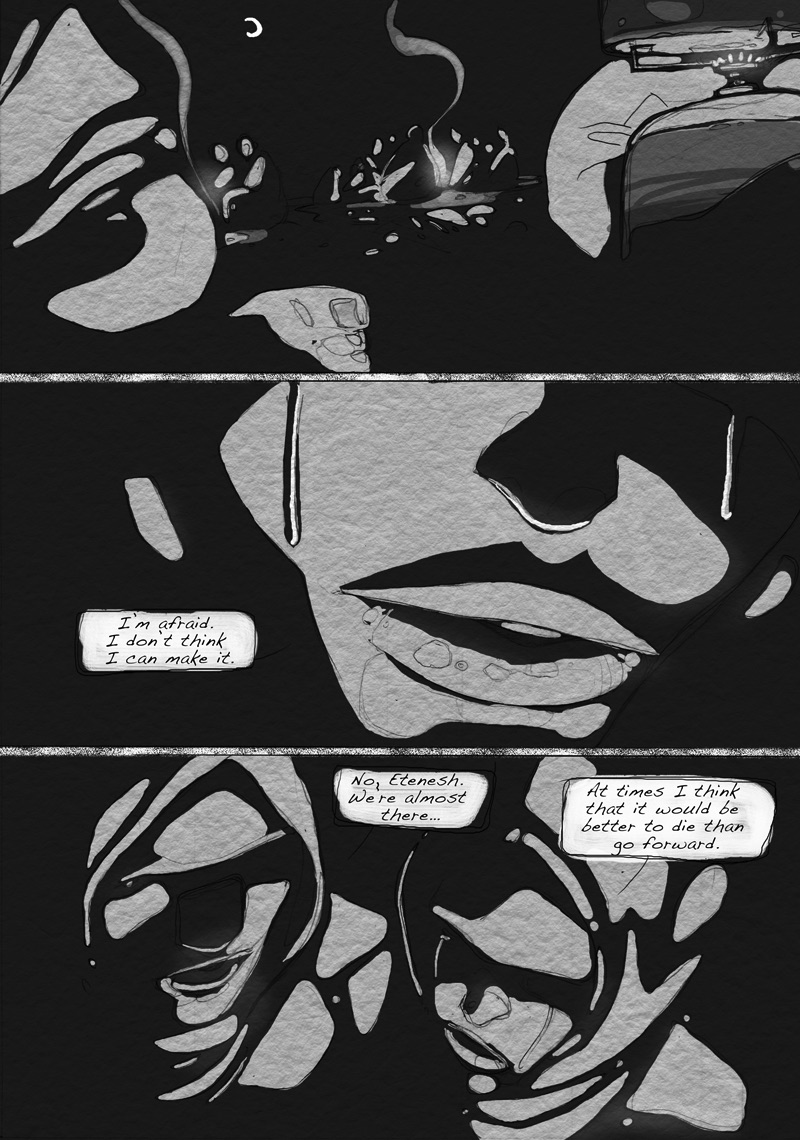

“I’m afraid. I don’t think I can make it.”

“No, Etenesh. We’re almost there . . .”

“At times I think that it would be better to die than go forward.”

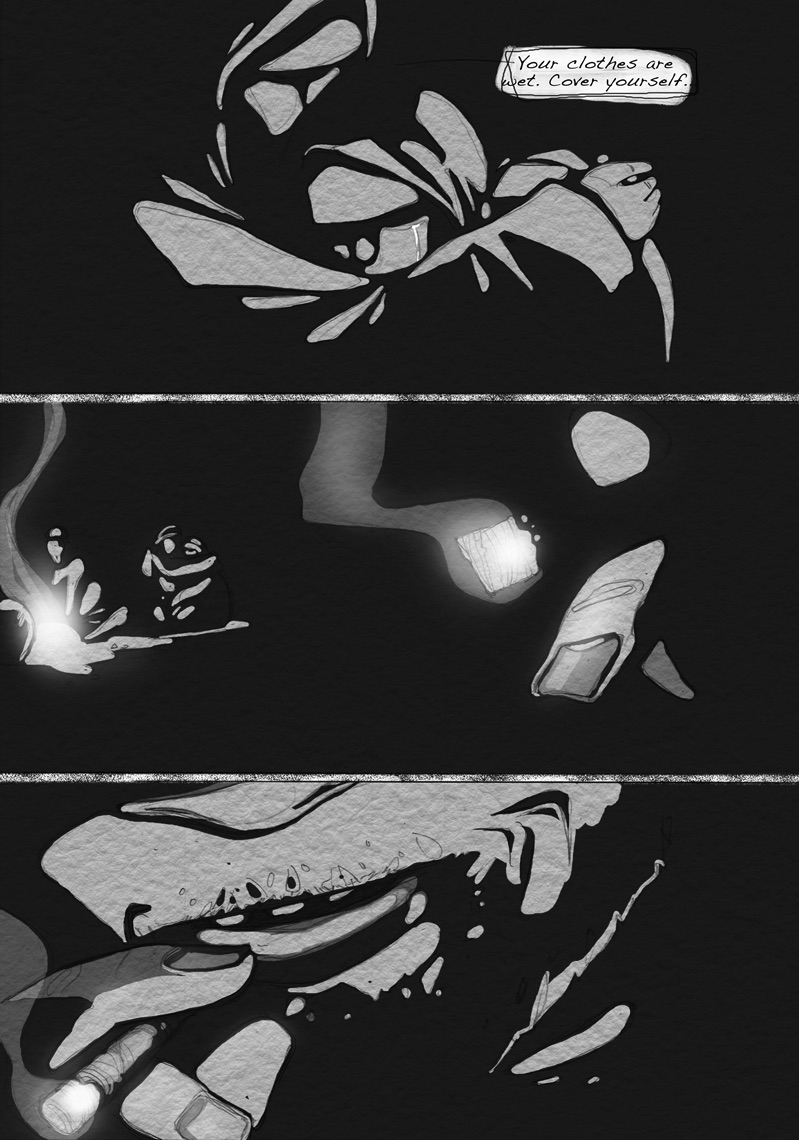

“Your clothes are wet. Cover yourself.”

“Maybe we’ll come across a truck that’s going back to Sudan . . . The border isn’t far from here. We could go back with them? Here we’ll die!”

“There are no trucks going back!”

“Who would want to go to Ethiopia? To Eritrea? To Somalia?”