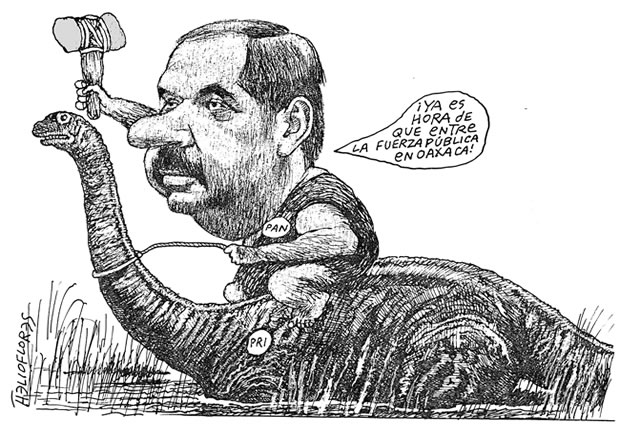

Figure 1. A politician from the party that now holds the presidential seat, riding the PRI dinosaur, says: “It’s about time troops and police enter Oaxaca!”

A legendarily short story by Tito Monterroso reads, in its entirety: “Y cuando despertó, el dinosaurio todavía estaba allí” (“And when he awoke, the dinosaur was still there”). This expresses my feelings about the PRI perfectly; when I was born, when I first opened my eyes, it was the dinosaur that welcomed me to the world. The PRI (Party of the Institutionalized Revolution) was founded by President Plutarco Elias Calles in 1929 as the PNR, the National Revolutionary Party. Later on, President Lázaro Cárdenas changed its name to PRM, the Party of the Mexican Revolution, and allied it with the labor unions. In 1946 it adopted the name PRI, the name it went by until it fell from power in 2000.

Figure 2. Cartoon related to the Lydia Cacho case: Puebla’s Governor in dialogue with the pedophile impresario who Cacho denounced in her book. “I’ve punished the bitch.” / “Did the son of a bitch think of herself like a god in power?” / “Nah! She thought she was a woman with human rights, what an asshole.” / “Beware, let’s hide!” // “What the hell’s happening?” / “I think there are elections at the State Workers Union.” / “Groar” / “Better get going, I’ll send you some canteens filled with cognac!” “?”/ “Calm down, nothing will happen. The Madrazaurus is just pretending he’s gaining on me.” / “What’s going on?” “I’m up in the polls one more point.”

In Mexican parlance, those who controlled the PRI were “dinosaurs.” Tied to this party, unluckily but inevitably, was the Taller de la Gráfica Popular (TGP), founded in 1937. The Taller de la Gráfica Popular was a sibling of the Mexican Muralists—themselves, like the PRI, offspring of the Mexican Revolution—but the TGP chose to work in a different medium, one that could be widely distributed by engravers and printmakers. Leopoldo Méndez, the TGP’s guiding light, kept the TGP going for the first twenty-five years. Alfredo Zalce and José Chávez Morado were its most renowned artists, along with David Alfaro Siqueiros, who was a muralist as well. The goal of the TGP was to make revolutionary art for the masses, to educate them, to be their political guide, to disseminate “ideological propaganda,” and to outmode bourgeois, individualist art. According to Humberto Musacchio, who recently published a useful, thorough, and beautiful volume on the TGP, “it voiced, in a Hegelian way, a perpetual movement toward the perfection of the State.”[1] Thus, it’s no great surprise that the TGP was associated—not entirely comfortably—with the Communist Party.

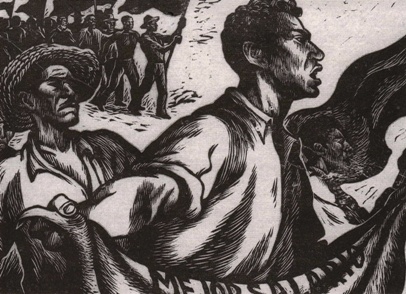

Figure 3. Alberto Beltrán, “The Strike of 50,000 Workers,” Mexico City, 1955, TGP. Linocut.

Politically the TGP felt much greater affinity with the Soviet Union than the United States, though their work was not appreciated in the U.S.S.R, where it was deemed too subjective, and was disliked for its expressionist tendencies; its “simplifications that derive from the Cubism,” especially in Alfredo Zalce’s work, reminded them of “madhouses or nightmares with grotesque figures.”[2] Conversely, the TGP did not appreciate Stalinist art. In an interview with Elena Poniatowska, Leopoldo Méndez said that what he really disliked (lo que sí estaba mal) in the 1939 New York Pavillion was the Soviet art. He found it stiff and academic; too much content, too little artistry. But the TGP wanted to appeal to the masses, to be utilitarian, to transmit a blunt political message. They did not want to produce “bourgeois art,” which they believed was nothing more than a commodity for those who could pay for it, which is to say “pointless trash, nonsense, art for the privileged minority” produced by ” the donkey artist that stains the canvas with its tail. Instead, they would produce art for all, arte popular. They believed realism was the best way to reach the people. They promoted national pride, agrarianism, the nationalization of oil, unionization, Jacobinism, anti-imperialism, and the struggle against the horrors of Fascism and Francoism.

When they first started working together, the TGP declared: “This workshop is born with the intention of stimulating the production of visual art that will benefit the people’s interests, and with this objective in mind will gather as many artists as possible to work on a common project, and strive for collective production. . . . All production of the members of this workshop, be it individual or be it collective, can be realized if it does not favor the reactionary forces or Fascism.” This position was similar to that of the manifesto published in 1924 in the Journal El Machete, signed by Xavier Guerrero, Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and other founders of the Union of Techinical Workers, Painters and Sculputors: “Our social reality is one of transition from an archaic order to a new order. Those who create art must strive to include in their work clear ideological propaganda for the people, art armed for combat that makes people aware of their history and their civil rights. Beauty will nourish their [the people’s] sensitivity and art will preserve their rich traditions.” It was also similar to the LEAR (Revolutionary Writers and Artists League) manifesto of 1936 (signed by Juan de la Cabada) in which the members called themselves “intellectual workers focused on the struggle against fascism, imperialism and war.”

To achieve these goals, they drew upon characters, scenes and mottoes from the Mexican Revolution, as did most of the Muralists and the PRI, for its official propaganda. Many of their prints were based on the Casasola photographic archives, which recorded Mexican life from 1900 to 1940, from the details of daily life to portraits of revolutionary leaders and anonymous fighters. From the late 1930s, this group of artists made public art: paintings, booklets, fliers, broadsides, banners and signs for demonstrations, floats for parades and anti-fascist demonstrations. Their workshop provided innumerable posters that covered the city walls and, according to Juan de la Cabada, often vanished as soon as they went up, removed by people who used them to decorate their homes.

Their preferred medium was linoleum: prints made with it produced strong contrasts, and it could be carved with the speed necessary to complete their social duties. One of the first “productions” of the TGP was the 1938 Calendar for the Universidad Obrera de México–the Proletarian University of México–where Méndez worked. That same year the TGP produced posters for the Mexican Workers Union, which would become one of the most corrupt institutions to ever exist in Mexico. They also produced propaganda for the Communist Party, including a catalog of twelve lithographs called La España de Franco (Franco’s Spain), and the cover of an artists’ portfolio, En el nombre de Cristo (In Christ’s Name), which celebrated rural teachers murdered by religious fanatics in the Mexican region of El Bajío.

In 1940 the TGP printed 32,000 posters to promote lectures at the Liga Procultura Alemana (the Antifascist Pro-German Culture League); held their first collective exhibit; and opened a lithography workshop, run by Kiloman Zoclo, a Czech artist living in exile in México. In 1942, the TGP founded a publishing house, La estampa mexicana, which was directed from 1943 to 1946 by George Stibi, an anti-fascist German refugee.

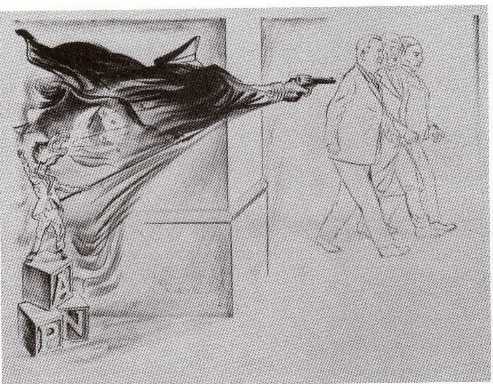

Figure 4. Leopoldo Méndez, “El gran atentado”

In 1944 the TGP attracted the sympathy and collaboration of a variety of renowned artists when one of Leopoldo Méndez’s pieces was censored by a gallery. The piece was “El gran atentado” (The Assassination Attempt), representing the intent of the PAN (Party of National Action, then an upstart challenger, today the party in power) to murder president Manual Ávila Camacho–who belonged, like all Mexican Presidents over the past seven decades, to the PRI. The TGP received support from the major muralists, Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco, as well as from Miguel Covarrubias and Carlos Mérida. Some members that had abandoned the TGP returned, including Raúl Anguiano, Luis Arenal, Alberto Beltrán, Castro Pacheco. Support even came from beyond Mexican borders, from the Ecuadorian artist Galo Galecio and the Venezuelan artist Héctor Poleo who joined the TGP, as well as a number of American artists who expressed sympathy for their fight for freedom of expression, including Robert Mallory, Jim Egleson, Eleanor Coen, and Marshal Goodman, among others. Three highly regarded critics–Paul Westheim, Raquel Tibol, and Antonio Rodríguez, all of whom were born and raised abroad and became Mexican–championed the TGP. Westheim wrote: “Relief printing made in Mexico after the Revolution deserves its own chapter in art history . . . for its quality and artistic genius.”

The TGP suffered difficult times as well: some of their members ended up in jail in 1940 when, urged by Siqueiros, they took part in a plot to assassinate Trotsky; their credibility suffered at the end of the Second World War, when Siqueiros returned to México and rejoined the TGP, and they supported Miguel Alemán’s candidacy for the presidency. Their support of Lázaro Cárdenas made sense, but Alemán had no revolutionary instincts. There were also disagreements with respect to the distribution of the income from their work: should artists keep their revenues, or turn them over to the Communist Party? It was not only the TGP’s support of Miguel Alemán and its affiliation with Siqueiros that cast a shadow over the TGP. If their goal was to be “revolutionary,” their link to the PRI was a colossal ball and chain.

In 1954, the year I was born, the TGP was twenty years old and held in high esteem. During the Mexico City Book Fair in 1956, thousands of people visited the TGP’s stand, where an impressive 30,000 prints were sold. Everybody knew their work. The TGP was part of the national landscape, just like the two volcanoes that overlooked the valley of my childhood (the Popocatépetl and Ixtlaccíhuatl, now obscured by smog), just like the cathedral in downtown Mexico City, and just like the PRI and the Muralists. The dinosaur was awaiting me when I first opened my eyes.

In the very early seventies, when I became a young poet, how could I have appreciated the value of the TGP? They were dinosaurs! I wanted to distance myself from them as much as possible. To my generation they were no different from the hideous PRI.

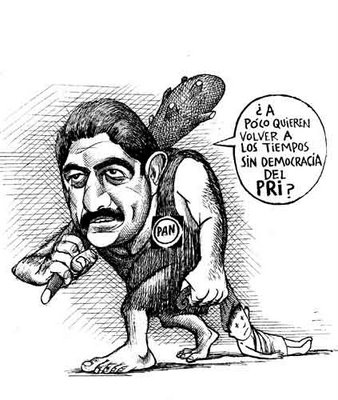

Figure 5. Cartoon by Gonzalo Rocha. “Don’t tell me you want to return to those days without democracy, the PRI’s?”

It has taken me a long time to appreciate the value of their work and understand it in its proper context. At that time, the PRI was our “natural” enemy; we did not see in it any of the qualities it in fact had. And as an artist myself, and as a writer, I had other reasons to dislike the TGP. For the TGP art had to be propaganda, had to provide the answers emphatically–instead of asking questions and raising doubts. Their approach completely failed to arouse my sympathy. Also, their methods didn’t seem to work.To my teenage ears, it was like the TGP were singing Nancy Sinatra’s song “These Boots Are Made for Walking.” Their art was supposed to be a tool to help society walk toward a fairer future, but they were tethered to the Party–the perpetrators of the Tlatelolco murders, the architects of the disastrous Mexican government. (We only suspected then what has recently been officially acknowledged in the National Security Archive’s 2006 report: from 1964 through 1982, hundreds were murdered or “disappeared,” thousands more were tortured, illegally detained, or subjected to government harassment.)

The TGP’s boots were uncomfortable, even painful, for all their boasting that they were made for walking. Their work may have been beautiful. But to my eyes their appeal was part of the problem. I preferred to wear huaraches, not because they were sloppy or nationalistic–I didn’t think they were–but because they were in their own way elegant and subversive of the status quo ruled by the “Revolutionary” Party. And they were also cosmopolitan: young people were donning them worldwide. We all wore huaraches with neolite soles–the medium which, by this time, the TGP preferred, since linoleum had become expensive and inaccessible at the end of the sixties. They were now practicing, as one of their friends put it, “suelografía” (sole-cut) . . . But still their boots were made for walking.

In addition to the TGP’s practice of “useful” art, and their link to the PRI, there was another notable aspect to their work. The artist and architect Juan O’Gorman wrote that in the sixties their work gave off a strong impression of sadness. Méndez agreed and added: “People need beautiful things just as much as they need warnings against evil, which are unpleasant albeit important. We must provide both, especially uplifting and inspiring work, which is necessary at all times in all places. Though it is in fact excellent work, it gives the impression that México is a country which radiates sadness.” And inside the TGP, things were not really working. According to one of their members, Márquez Rodiles, there was “fatigue, disillusion, anxiety, hurriedness, sectarianism, intolerance, opportunism, and fear”–these were the words of an insider!

Taking all of this into account, it’s no surprise I felt drawn to the next generation, the post-Mexican school, the one that wanted to demolish, as José Luis Cuevas put it, the “cortina de nopal” (cactus screen)–as well as to the “new generation” of authors: Jorge Ibargüengoitia, Juan García Ponce, Salvador Elizondo, Inés Arredondo, and the Spanish refugee Tomás Segovia. They abhorred nationalism, despised the idea of “useful” art, and detested the muralists’ demagoguery. We young writers and artists felt closer to them, for we did not want to be Mexican artists dealing with the Mexican issues of the Mexican Revolution as represented by the PRI. We wanted a dialogue with the rest of the world, and with other possible political solutions. We wanted to deal with the now of Mexican life, and with the very interesting things that were happening abroad, in Latin America, in Europe, and in the U.S.A. And we wanted our art to run free—yes! to be what the donkey’s tail ordained. I adored Marguerite Yourcenar as much as I felt attached to Juan Rulfo or Juan José Arreola. And I felt closer to Katherine Mansfield and Angela Carter than to the novelists of the Mexican Revolution.

It’s important to bear in mind that though the PRI was not all murder and dirty war, neither did the TGP produce only provincial and “bad” art. The extraordinary work of most of their members is indisputable. But for my generation, which came of age during the decadence of the PRI, they were inevitably tied to the Dinosaur. They both claimed to be children of the same Mexican Revolution. And the TGP’s links to the State and its rhetoric had sullied them in our eyes.

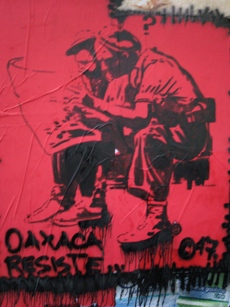

Figure 6. Oaxaca. Photograph by the author.

Recently, the TGP has been given a new lease on life. In Oaxaca–not long ago the favorite spot for tourists with good taste, now a city in uproar–a group of exceptional young artists has sprung up that could be called the new children of the TGP. No more linoleum or neolite, now it’s spray and stencils. The quality of their work is astonishing–though inevitably uneven, given that they must work in a rush to avoid being captured and imprisoned. Is this the beginning of a new era in the TGP’s history, one in which a new generation will draw from the best they had to offer while leaving behind those aspects that are dated and deeply problematic?

1. Taller de la Gráfica Mexicana (Colección Tezontle, FCE, 2007). This and all other translations are the author’s.

2. Helga Prignitz, El Taller de Gráfica Popular en México, 1937-1977 (INBA, 1992).

First presented as a lecture, “The Struggle is on the Walls: Antecedents and Inheritors of the TGP,” October 7, 2007, at the Princeton University Library, in conjunction with the opening of the exhibition El Taller de Gráfica Popular / The Workshop of Popular Graphic. Copyright 2008 by Carmen Boullosa. By arrangement with the author. Translation copyright 2008 by Samantha Schnee. All rights reserved.