And then out of the blue a lady stands up and raises issues of race, bringing to the fore matters that would usually be marginalized. She has dark skin and silver hair and introduces herself as a retired secondary school teacher. Her voice is smooth as porcelain, and she speaks with that mixture of charm and candor you get in older women who are past caring for courtesies. She points out that there were more Black slaves in Portugal than in any other country in Europe.

We’re at Belmonte Palace, in Lisbon, on the top of the hill by the castle, where a group of writers and academics have gathered for a conference on the history of the city. Some of the delegates are “French authors of international renown,” according to the program, and many have abandoned the cold that still grips their homelands in the European north to bask in the first days of Portuguese spring. Today’s discussion focuses on the presence of Black slaves in the city, going back through the centuries and identifying traces of them in the toponymy of today. An image of the painting Chafariz d’El Rei (The King’s Fountain) is projected onto a wall behind the stage. Concepts of Lusophone miscegenation have the historians enthralled.

But the woman with the silver hair, whom I will come to know as Leopoldina, talks about the people in the painting as if they’re old acquaintances: Blacks, slaves, Moors; men and women; names and dates. She even speculates on how one ought to pronounce sixteenth-century Portuguese and what the era’s most common insults and curses would have been. She wears a brown shawl draped over a knitted white cardigan, denim jeans, and brown cowboy boots, a look that initially strikes me as being almost too neo-hippie. Later on, during one of the breaks, I see her flicking through a book about rice cultivation in the palace library.

A few days earlier, I’d received an unexpected phone call. Besides the experts in the field and the distinguished men and women of letters, the organizers thought they ought to invite someone to represent the ethnic minorities of what remains a predominantly white city. Much to my surprise, that someone was me.

The organizers couldn’t have known it, but the representative they’d chosen—a mixed-race man from São Vicente, Cape Verde, an archipelago off the west coast of Africa that was colonized by Portugal—was in the midst of a historical reckoning of his own. I’d recently returned to Portugal, brought back by a death, and was experiencing a profound sense of guilt for having abandoned the country of my birth for a second time. I’d become preoccupied with matters of heritage and background: how my ancestral trajectory was both personal and typical—one more family of Cape Verdean immigrants—and how, in some abstract way, perhaps through that sense of melancholy we Portuguese speakers call saudade, my own journey was connected to that first voyage, in 1444, when 235 Africans were brought to Portugal with shackles on their feet.

*

At the end of the morning session, when speakers and delegates head for lunch, I pick up the printout of Chafariz d’El Rei and walk down the hill to Alfama, to see what remains of the fountain depicted in the historic painting.

Unexpected emotion wells up in me as I walk. The people of this picture would’ve had no idea they were being watched and reproduced on canvas; indeed, it would doubtless have come as a surprise to learn their insignificant existence had even been noticed. What would the painter have been thinking? An anonymous foreign artist who, at some point between 1560 and 1580, decided to compose a street scene in a manner then typical of northern European painting, and inadvertently produced a picture of unparalleled documentary value.

The mediocre quality of the artwork—there is no avoiding the fact that the artist had more enthusiasm than talent—is more than compensated for by its importance as a historical record. Of the 136 people depicted—who, yes, I took the trouble to count—seventy-nine are Black, including seven children caught up in the hustle and bustle of the adults. At first glance, it is unclear if any of these people are captives; indeed, I’d say considerable effort is made by some of them to hide this fateful fact, or at least to ignore it. They’re taking part in the daily routine of queuing to fill up water jars, as many as could feasibly be carried, while indulging in a little conversation. It doesn’t take too much imagination to hear the cacophony of voices exclaiming in Balanta, Papel, Manjak, Mandinka, Fulani, Beafada, Serer, Soninke, and Mende, joking and laughing, protesting and consoling, lamenting lives that had nothing to offer them, Black men and women—and slaves, besides.

I can almost smell the odors coming from their bodies, awkwardly wrapped in European clothes. The water girls look sensual in their bright, long skirts, the pitchers on their heads likely one of the details that most caught the painter’s attention. The artist would probably never have seen so many Black people gathered together—noisily, festively, lewdly—in a public space before. Sixteenth-century Lisbon was like nowhere else in Europe, populous but with wide-open spaces, a city that had nourished and reinvented itself thanks to the arrival of spices from new worlds. Little wonder the outsider felt compelled to arrange a street scene

containing such unusual sights.

The Chafariz d’El Rei itself occupies the right-hand side of the painting, the artist being primarily concerned with the world that revolved around the fountain’s six spouts, each one painted white and shaped like a horse’s head. Above them, three arched vaults are supported by two pillars, likewise painted white, creating an atrium sixty feet long and thirty feet deep. The pillars and the vaults, as well as the terrace above the arches—where plants can be seen growing, lilies perhaps—are adorned in Moorish style with carvings and decorative flourishes. The middle arch features the royal coat of arms at its center, and the two side arches bear the heads of animals of some kind. The fountain’s entire portico, broad enough to shelter anyone who might have to spend several hours queuing there, is tucked in between two towers left over from the ancient Cerca Moura city wall.

The good reputation enjoyed by the water in the area was likewise ancient. The Roman architect and engineer Vitruvius references Lisbon’s eastern waters in book eight of his De architectura, a volume dedicated to hydraulic constructions. ʿAbd al-Muʾmin, the first caliph of the Almohad empire, wrote a description of Lisbon in the twelfth century in which he highlighted the city’s famous hot springs (al-hamma, in the Arabic, which gave the Alfama neighborhood its name). Three centuries later, the Portuguese humanist philosopher Damião de Góis was equally impressed by the fountain, praising the construction of its columns and arches and the quality of its water, “pure and fresh and a great pleasure to drink.”

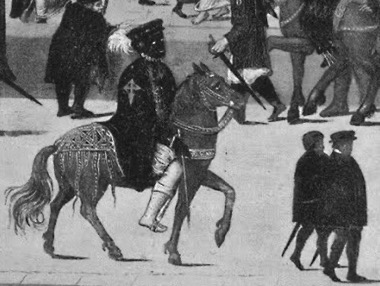

As the painting shows, the fountain previously opened out into a rectangular space, a sort of town square built on slightly lower ground to the road. Some people linger and chat in a leisurely manner at the foot of two stone steps, while others seem to loiter with no intent other than to quench their thirst and catch the latest gossip. A man makes expressive gestures, as if calling out to someone. At center stage, a Black man and a white woman seem ahead of their time in dancing a sort of tango together. Two men, New Christians perhaps, appear to be weighing up the risks of an ambitious commercial venture, as befitted Lisbon’s glorious days of old. On the right, three bearded men look on as a majestic knight rides past. And as if to prove that, irrespective of time or latitude, there’s always more to things than meets the eye, this horseman is Black.

The men’s apparent curiosity and gnostic acceptance of the enigmatic figure, dressed in a cloak of the Order of Santiago, echoes the painter’s evident fascination. The loftiness of the knight’s position and the elegance of his horse—a sacred animal—give him a dignity above and beyond all the other people in the painting, thus undermining the entire social order the scene prescribes.

Who can he be, this chevalier, violating established norms with his nobility? Can what these half dozen brushstrokes suggest actually be true? Could a Black man really have become a knight of the Order of Santiago?

The order was a military/religious group founded in Spain in the twelfth century to protect pilgrims on the way to Santiago de Compostela and the shrine of Saint James (Tiago in Spanish and Portuguese equates to “James”), a route now popularly known as the Camino. A Portuguese chapter, known as the Order of Saint James of the Sword, was soon established, with membership restricted to noblemen. There would eventually be three such orders in Portugal—Saint James of the Sword, Avis, and Christ—and all had similarly exclusive rules of entry, but they occasionally made exceptions. Francis A. Dutra, an American scholar of early modern Portugal, has studied these orders, and his findings provide clues as to who this Black knight might be.

In the early eighteenth century, a record was compiled of all the men who’d required special dispensation to gain knighthoods in the three orders. These dispensations were divided into different categories—age, illegitimacy, ancestry, and so on—with twenty-seven names listed under “Mulato and/or Descended from African slaves.” Most were biracial, the descendants of the sort of people shown in the Chafariz painting, but Dutra determined that seven of them were Black: one in the Order of Avis, three in the Order of Christ, and three in the Order of Saint James. Dutra also notes that Manuel Gonçalves Doria, a soldier born in Brazil, was the first Afro-Brazilian to become a knight of the Order of Saint James, but that was not until 1628, many years after the painting.

Of the three Black men awarded knighthoods of Saint James of the Sword, two were noblemen from royal households, while the third, João de Sá Panasco, was a court jester descended from slaves. Given this background, Panasco is, it is argued, the most likely of the three to have frequented the fountain area. The man in the painting also fits what we know of Panasco’s description: the clothes, the stance, the touch of gray in the hair.

If it is Panasco—and it’s widely held that it is—then his parading through the square, a meeting place for Black men and women at the heart of the kingdom, acquires a certain poetic quality. Born in the Congo, Panasco was brought to Lisbon as a boy and put to work in several houses before finding his way into the court of King João III and Catherine of Austria. There he became a habitual presence at the royal table, appreciated for his amusing jokes and stories, and known for his witty and spirited retorts if mocked: “For the Portuguese gent, happiness consists of being called Vasconçelos, owning an estate, having six hundred thousand réis of monthly income, and being stupid and useless.”

Panasco was certainly much more than a “fly in the milk,” as Dom Francisco Coutinho, the Count of Redondo, described him after finding him sick in bed, wrapped in white sheets. In 1535, while still a teenager, he was sent to North Africa, under the command of the king’s brother, Prince Luís, as part of the Portuguese contingent in Charles V’s Conquest of Tunis. In the siege that followed the sinking of the sea fleet of Hayreddin Barbarossa, Panasco noticed a small dog sitting frightened under an olive tree. Impervious to the cavalry charges and flying arrows, Panasco rode across the battlefield and picked up the puppy, an Anatolian shepherd that he took back to Lisbon and looked after for the rest of his days.

Panasco was awarded the habit of the Order of Saint James for his services to the crown sometime between 1550 and 1557. In later life, however, ground down by racist attitudes and the stigma of his background, he became overwhelmed with bitterness and took to drink. Looking at the painting again, I wonder what the other Black people, the slaves and free slaves he crossed paths with in the royal court or on the city streets, made of him. He was a man without a mask, but at the time this made for a split personality.

The painting also depicts a number of Portuguese worthies, including noblemen, some of them standing, others on horseback and dressed in black. Two policemen carry away a drunken Black man, a detail mentioned by Leopoldina at the conference: alcohol-related depravity prompted the Lisbon Town Hall to ban Black people from drinking wine in taverns or indeed from entering them. Alcoholism was actually a double vice, for slaves were forbidden from carrying money or having possessions of any kind, meaning that if they were to buy wine, they would have to steal.

Black slaves were not considered people but things: in Portuguese there is a distinction between the word negro, which describes a Black person, and preto, which describes a black thing; Black slaves were called pretos. (For this reason, negro is not taken to be an offensive term in Portuguese, whereas preto continues to be used as a racist slur.) “Things” could not buy other things, like wine. Nor could they ride around on horses, not least because being mounted conveyed indisputable dignity, in this case the dignity of a knight.

Elsewhere in the picture, a young Black man is rowing a boat while another shakes a tambourine, doubtless making the pleasure cruise being enjoyed by a white couple that bit more pleasurable. Another Black man stands with a pot over his head, perhaps performing some kind of street theater.

Protagonism aside, it’s worth clarifying that, with the exception of Panasco, all the Black men and women in the picture are preserved for posterity like nonspecific blackbirds. Their heads are mostly jet-black blurs with barely defined eyes, ears, noses, or mouths, as if the artist could only reflect the church decree that Black people had no souls.

If the Christian hereafter was a place of gardens and angels, then the pagan one was a sea of shadows and chill winds. Having no soul denied Black people salvation and excluded them from the grounds of Christian cemeteries. Their destiny was the Poço dos Negros (literally the “Blacks’ Well,” though it was a mere pit) and the “lime shroud,” a colloquialism born of the fact that the pit was periodically disinfected with quicklime.

As I walk the city streets now, it’s hard to imagine the stench of dead bodies that would have floated in the air then, entering homes and getting up the noses of noblemen and commoners alike. Lisbon would have been a filthy place, polluted as much by credo and small-mindedness as by lack of hygiene. After being dumped in the pit, bodies were smothered in salt, lest their rotting flesh and exposed bones contaminate the city’s water and spoil the pure, fresh taste that Damião de Góis had described.

The 1444 shipment of enslaved Africans landed at Lagos, in the Algarve, but some of the 235 men, women, and children were brought to Lisbon. They were the spoils of raids in Arguin and Guinea, transported by men in the employ of Prince Henry the Navigator. The prince’s men had to overcome adversity—fighting, killing, and fettering—to deliver their cargo, and, as they saw it, they managed to do so because the Good Lord favored them over all other living creatures, not least the seminaked savages who’d vainly sought to hide their children in dusty fields. Those 235 were the first of their kind to experience the strange place of exile that was the Europe of Christ and salvation.

From Under Our Skin by Joaquim Arena, translated by Jethro Soutar. Copyright © 2023 by Joaquim Arena. Translation copyright © 2023 by Jethro Soutar. Published by Unnamed Press. Cover design by Robert Bieselin. Typeset by Jaya Nicely. All rights reserved.