Translator’s Introduction

1. Reflections on the Manhwabang

I grew up in South Korea in the 1960s during the Park Chung-hee years, back in the day when comic books, or manhwa, were classified as one of the great social evils along with alcoholism, drug addiction, gambling, and prostitution. I lived in a neighborhood in Korea’s largest camp town, just outside the American Army base called ASCOM, so I witnessed the full range of these social evils, sometimes on a daily basis. But I was only a kid, and I generally avoided the other social evils by hanging out at the local manhwabang, the “comic book room,” a neighborhood institution where all the young local delinquents—mostly teenage thugs and schoolboys playing hooky—could be found.

South Korea called itself a democracy in those days, though it was a tenuous one that technically became a military dictatorship the year my family left, 1972, when Park installed the Yushin Constitution and disbanded parliament. He had taken power through the May 16th “bloodless” coup in 1961 while student protests were destabilizing the interim administration after the downfall of Syngman Rhee.

In the 1960s, Korea was still recovering from the devastating civil war that had left the country split in two and forever separated nearly ten million families. The South saw the North as a nation of fanatical Reds ruled by a megalomaniacal dictator whose major ambition was to infiltrate assassin spies below the DMZ and destabilize the struggling, peace-loving, capitalist, democratic counterpart. The atmosphere in the South was constantly tense, based on both a perceived and real threat. In the 1968 assassination attempt on Park, known as “The Blue House Raid,” thirty-one infiltrators came within sight of Park’s residence. The national manhunt that ensued after their botched mission resulted in the deaths of sixty-eight South Koreans and three Americans. In 1974, in another attempt, a North Korean assassin missed him and killed Park’s wife. Ironically, it was a member of Park’s own KCIA that finally assassinated him in 1979.

There was still a national curfew in the 1960s and 70s, a constant reminder of local military power and the military threat from the North. Live munitions were still to be found all over the country, left over from the war and from American exercises. Every season, the local elementary schools had educational campaigns: “Beware of Explosives!” or “How to Spot an Infiltrator!” along with the typical ones for “Fire Safety” and “Personal Hygiene.” Children were taught how to spot spies through their odd accents or cultural ignorance, and even visiting relatives from other parts of the country were sometimes reported to the local police.

I attended the U.S. Department of Defense school, so I missed much of this education and indoctrination. The American military school’s mission was diametrically opposite that of the Korean schools—since we were living in what was still an active combat zone (the Korean War having never officially ended), we were kept calm with familiar relics of “home” in America. But I saw all of my cousin’s pastel crayon posters for these campaigns, which also emphasized other services to the nation. I would play hooky and follow her entire school into the hills to pick caterpillars off the trees with wooden chopsticks—those were wonderful field trips, the entire hillside teeming with school children fighting off the infestations of natural pests to help with the reforestation campaign. I still remember my tin can full of fuzzy, squirming caterpillars and the terrible odor as they were burned in a kerosene fire. A couple years later, trucks came through the neighborhoods spewing thick clouds of DDT and all the children were encouraged to run behind for the healthful “antiseptic” benefits (there is a great representation of this anti-mosquito campaign in the opening credits of the Korean film Friends).

I have vivid memories of those days under the Park regime with its public education campaigns, national sanitation initiatives, and government ideology, all linked to images of the art I saw nearly every day: school projects, community posters, billboards, newspaper ads. I was learning to read by looking at the comic books in the neighborhood manhwabang. I can still narrate episodes of Korean classical history just as well as the story of the boy and his ink-spewing squid, and I remember the pictures that showed the dangers of playing with explosives (I knew from scavenging artillery ranges that the posters were rather inaccurate).

Korean comics were printed on the cheapest of all recycled paper stock—”shit paper”—and yet they were still were too expensive for a typical person to buy. Most stories were printed in multivolume sets of a dozen or so, or at least in ha (low) and sang (high) sets designating part 1 and part 2. The ink used for the interior printing was probably recycled from the mixed waste of colored inks from other press runs—it was never quite black, but usually a shade of blue ranging from a dark navy to a baby blue. In many books the color of the ink wasn’t uniform throughout, and it was often refreshing to go from a dark ink to a lighter one—sort of like a change of atmosphere or lighting in a movie or a play.

Customers could pay by the hour or get a bargain by paying a flat rate and sit inside the dark, cramped interior of the manhwabang all day. The walls were entirely covered with comics displayed on shelves made of molding strips nailed at three or four levels along all four walls. The comics, digest-sized by American reckoning, were displayed from these thin ledges with their covers facing out, each volume slightly overlapping the previous one to save shelf space. The entire interior of the manhwabang—sometimes even the inside of the sliding doors—was covered with these shelves. In winter, I imagine all the paper added to the insulation, though the manhwabang was invariably freezing, heated only with a single tiny stove that burned high-sulfur charcoal cylinders. The owner usually lived in a tiny single room that opened facing the stove, and the place was illuminated by two dangling forty-watt bulbs at night. After dark, you could rent comics overnight, and I would often come back after spending the day there to pick up romances and histories for my older female relatives. At a time when our neighborhood had only two households with television (which their owners used as a moneymaker, charging admission), the nightly comic book rentals were like our Blockbuster Videos.

These days, comics in South Korea are much like their counterpart in Japan. They run the gamut of genres, they are no longer stigmatized as a major social vice, their creators are international celebrities, and they are sold to the general public in brightly-lit manhwa stores and in 7-11-style all-night conveniences as single-volume graphic novels.

I miss the old days.

2. Mighty Wing!

What I have seen of North Korea (the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea) in photographs and film, and what I have heard and read of the country, reminds me of South Korea in the mid-1960s. The streets of Pyongyang are too clean and sparsely populated, to be sure, but much of what is visible and known of the outlying areas seems to be nearly half a century behind the South in terms of general development. One of the surprising features in rural areas is the anachronistic wood-fueled truck—something my older male relatives in the South recall from the era before the Korean War.

Ironically, one of the best descriptions of North Korea to appear in recent years is a comic book, Pyongyang, by the French animator/cartoonist Guy Delisle. Even if you have seen films and photos they do not come close to conveying the sense of scale, the emptiness, and the cold grayness of Pyongyang, which Delisle’s gray-toned comic book memoir so effectively evokes.

Comics are unexpectedly effective in their ability to convey complex themes, and their form makes the reader unusually vulnerable to thematic content. The power of the Holocaust narrative in Art Spiegelman’s Maus, for example, is amplified by the fact that its “funny animal” convention relaxes the reader’s defense mechanisms. Though the content of the narrative may be no more intense than that of another Holocaust narrative, Maus’s tragedies are especially poignant because they strike us in a place usually reserved for the nice associations and nostalgia we have for figures like Mickey Mouse. Maus’s target audience, of course, is adult, and much can be said about how American comic books like Uncle Scrooge prey on children’s vulnerabilities to promote western ideology (mostly capitalism), but because we live in the culture from which these works arise, it is difficult to discuss the issue of the conscious intentions behind them.

With North Korean comic books, it is an altogether different matter. They are produced quite explicitly to teach children the “Great Leader” Kim Il Sung’s ideology of Juche, or “self-reliance.” North Korean writers and artists, since they must work under state supervision, are all taught the rules of Juche and how they must be applied. Kim’s Juchemunhaknon, the North Korean theory of literature (similar in some ways to the old Soviet Socialist Realism), includes a section with instructions on writing for children.

I think I was initially drawn to translating the North Korean manhwa by how they reminded me of their South Korean counterparts of the 1960s, my formative reading materials in the manhwahbang in my neighborhood. But early in the process of studying the comics, I realized I had stumbled upon a remarkable source of material for cultural analysis.

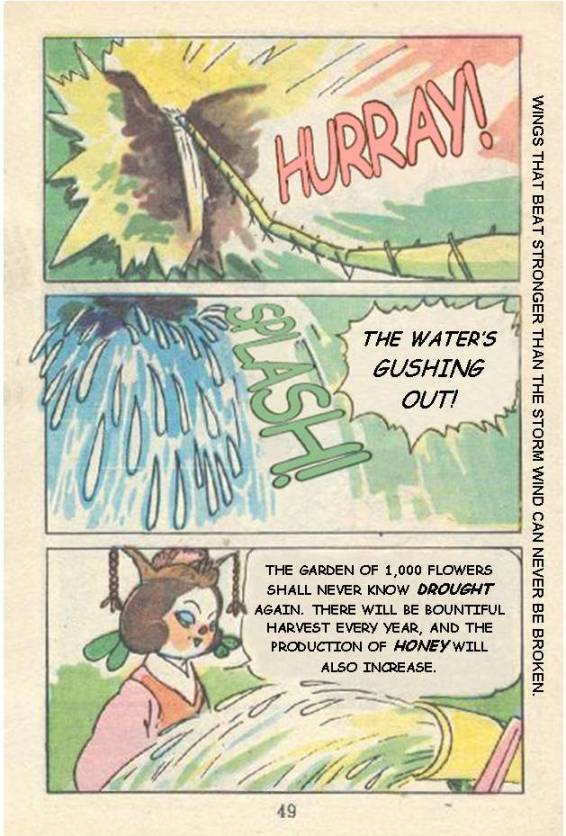

By 1994, the year Mighty Wing was published, which was also the year Kim Il Sung, the “Great Leader,” died, the outside world knew about the drought conditions in North Korea. By 2000, all of this was commonly known. North Korea was receiving hundreds of thousands of tons of food and tens of millions of dollars in aid. The famine that hit North Korea by the mid 1990s was devastating. The consistent pattern flooding and drought caused by climate change ultimately resulted in the deaths of more than a quarter of a million people as reported by the DPRK (some estimates say the true figure is up to three million). By the late 1990s, only half the population had safe drinking water.

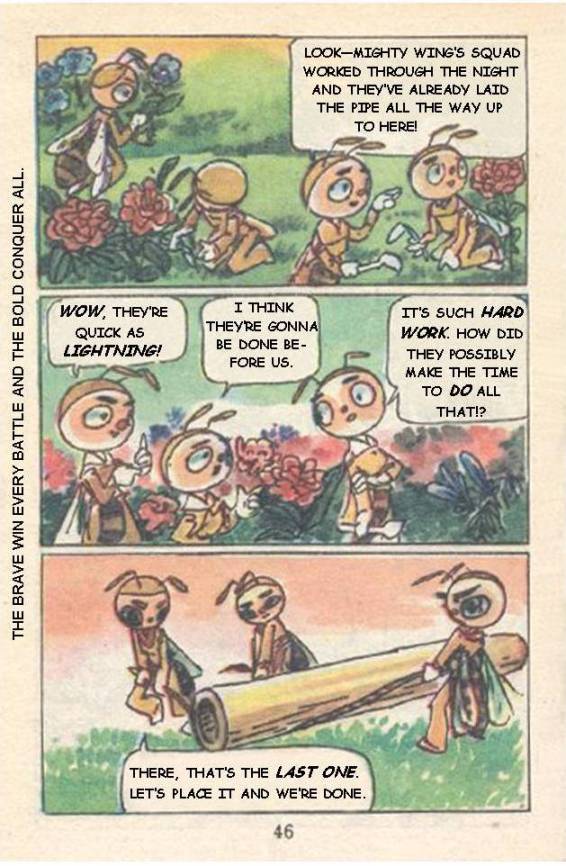

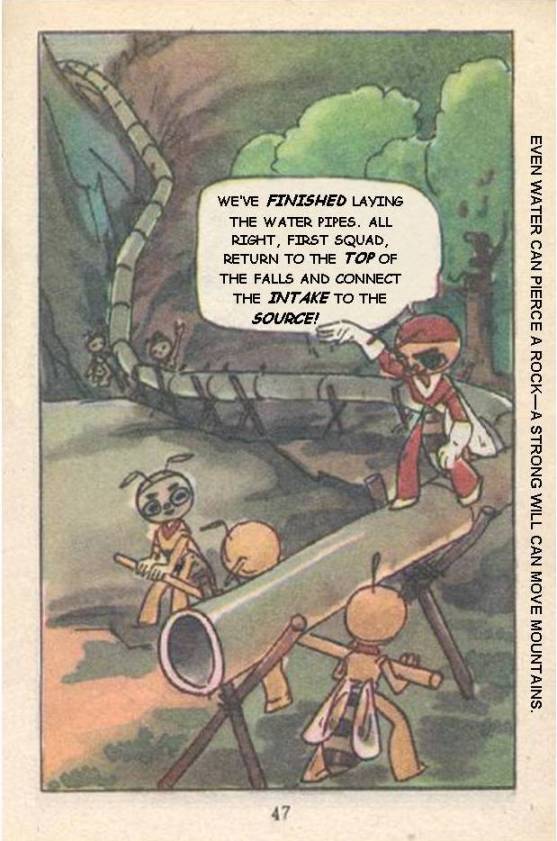

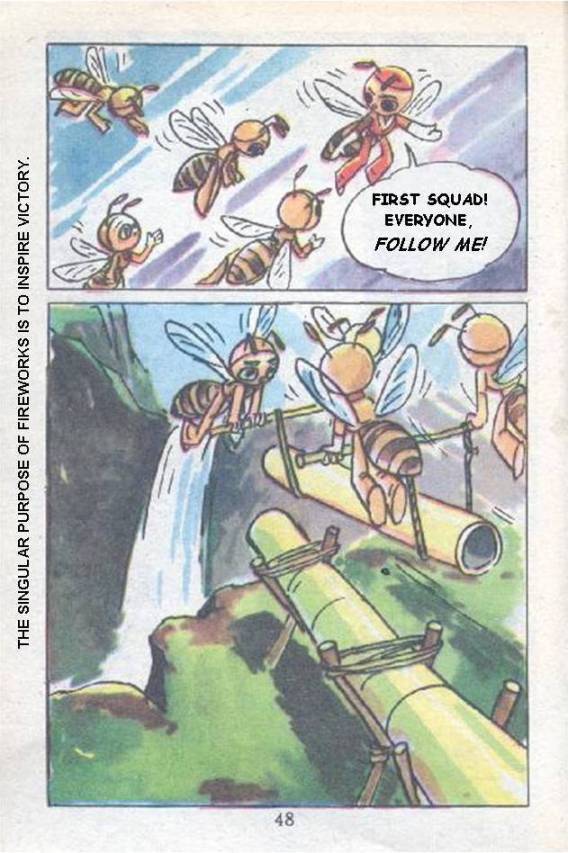

But the story in Mighty Wing shows that by that time, the country was already well aware of the drought and of the necessity for irrigation and for replenishing a depleting food supply. Since the publication date is 1994, it is likely that the book was produced in 1993, reflecting the concerns of the regime just prior to Kim Il Sung’s death in July of 1994.

The Queen Bee refers to a drought that has been ongoing, and the plot of the story features a traitor among the honeybees who willfully misallocates labor resources to build the Queen a country house instead of applying it to the construction of a much-needed aqueduct. Mighty Wing, the hero of the story, is the one who comes up with the idea of building an irrigation system to save “The Garden of One Thousand Flowers” to help replenish the supplies of honey.

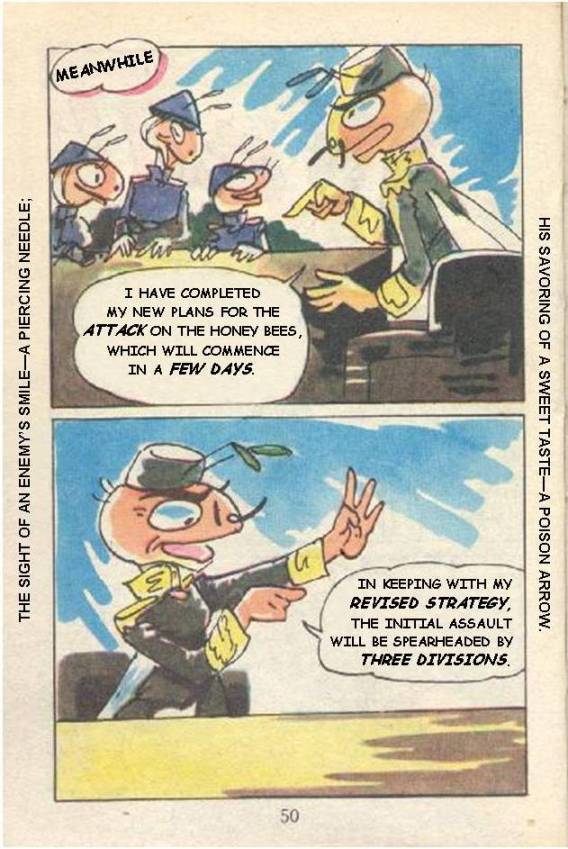

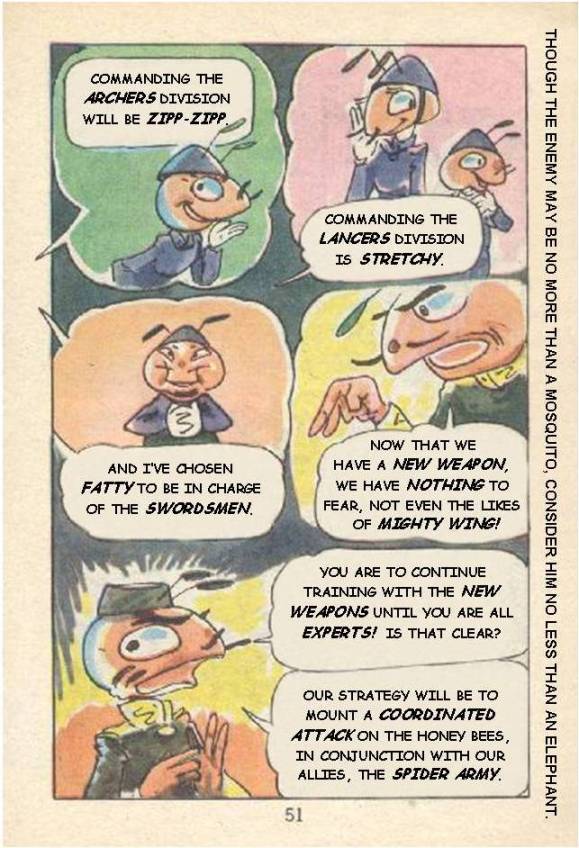

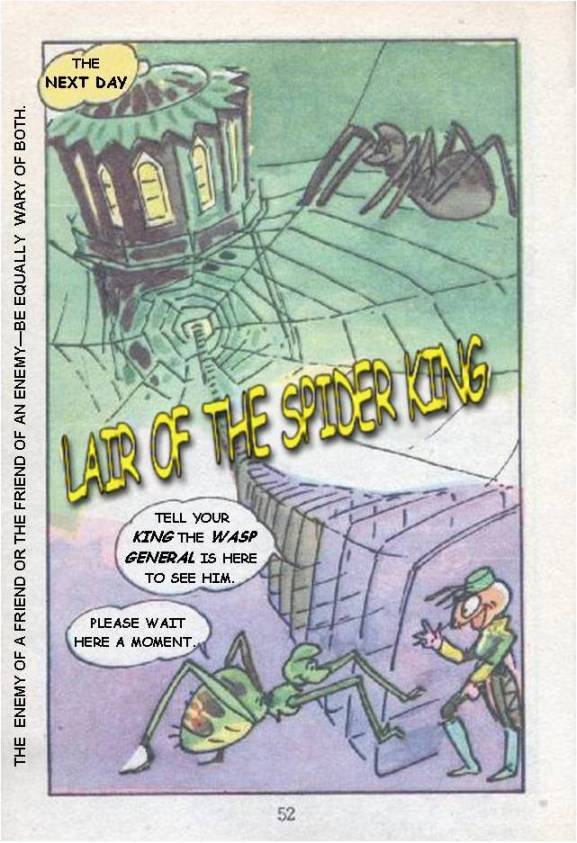

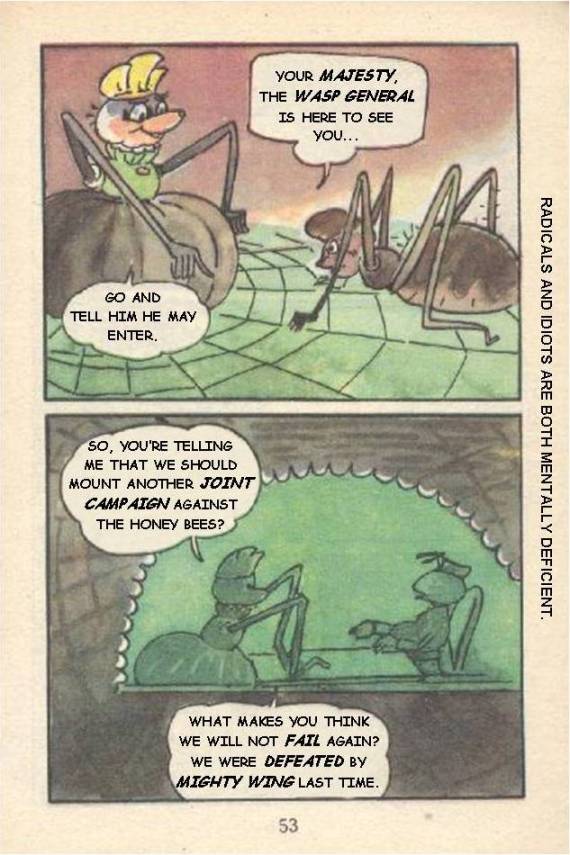

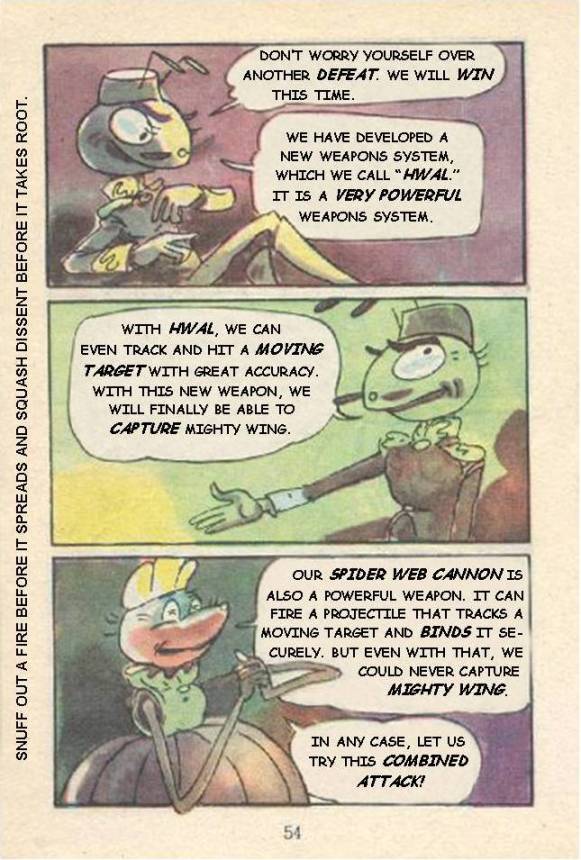

In this excerpt, we see that there is also an ever-present outside threat. The Wasp army, which had failed in an earlier attempt to conquer the Honeybees (due to Mighty Wing’s heroic efforts), has devised a new secret weapon, and when the Wasp General goes to meet with the King of Spiders, we see the symbolism of American/Japanese interests (represented by the Wasps, who are depicted in a way that draws on the North Korean stereotypes of the Japanese and Americans) coordinating with U.N. interests (the Spiders, whose web looks like the U.N. logo).

The Spiders’ weapons system is a net, able to trap moving targets, while the Wasps’ new weapon can hit moving targets at a distance (perhaps an inverted reference to the North Korean Nodong/Scud missiles tested in late May of 1993, which landed in the Sea of Japan to much international alarm—certainly a technology more advanced than the primitive hwal of the Wasps). I have kept the term hwal, which literally means “bow,” to make it sound slightly secretive. In Korean, hwal is a mugi, i.e., a weapon, and it resonates with haengmugi, which means “atomic weapons,” the threat America is constantly holding over the nation in popular representations.

What exactly is it that the invaders want from the Honeybees? Of course, it is their self-sufficient Juche paradise, the kingdom that relies on “The Garden of One Thousand Flowers,” which is the source of honey. The symbolism is borne out in nature. Common wasps often attempt to invade honeybee nests to steal their honey; the bees must defend their nest by stinging the wasps to death. Spiders and wasps are often mortal enemies of one another, but in this story, they temporarily ally with each other to conquer the bees. The traitorous general Zing-Zing, who has squandered the Honeybees’ resources, has sold out for corrupt Capitalist interests and attempts to corrupt the Queen Bee by building those country homes (which the North Koreans would associate with the Soviet-era custom of corrupt party officials and their elaborate country dachas).

To an adult western reader, the overarching symbolism of the state as an industrious beehive is painfully transparent. It is, in fact, quite familiar to us in common logos. For example, the Masonic symbol on the back of a U.S. quarter is also the logo for the state of Utah. The beehive also happens to appear on signage for the City of Poughkeepsie, where I live.

Mighty Wing plays with deep mythic symbolism. Bees were thought, by the Egyptians, to come from the tears of the Sun god, Ra. In North Korean symbology, the Sun God is, of course the “Great Leader” Kim Il-sung himself, whose name (since it is written in the phonetic alphabet) could be read as Kim (metal/gold) Il (singular, unifying/sun) Sung (star). Both Kim Il-sung and his son, Kim Jung-il, though male, were also carefully associated, by the North Korean media, with maternal imagery in order to suggest that the state was both father and mother to the people. Symbolically, they are both of the solar lineage and also Queen Bees to the nation of diligent workers. To deliver this symbolic story in comic book form, accompanied by the marginal paratexts that range from Aesop-like aphorisms to paranoid political slogans, demonstrates a masterful and double-edged application of Juche literary theory. On the one hand, it is a poignant message to children, directed at preserving North Korea’s natural resources and modeling devotion to the state; on the other, it is military/political indoctrination at its most insidious.

Introduction and translation copyright 2008 by Heinz Insu Fenkl. All rights reserved.