“But Comrade António, don’t you prefer to live in a free country?”

I liked to ask this question when I came into the kitchen. I’d open the refrigerator and take out the water bottle. Before I could reach for a glass, Comrade António was passing me one. His hands made greasy fingerprints on the sides, but I didn’t have the courage to refuse this gesture. I filled the glass, drank one swallow, two, and waited for his reply. Comrade António breathed. Then he turned off the tap. He cleaned his hands, busied himself with the stove. Then he said: “Son, in the white man’s time things weren’t like this . . .”

He smiled. I really wanted to understand that smile. I’d heard incredible stories of bad treatment, bad living conditions, miserable wages and all the rest. But Comrade António liked this line in support of the Portuguese and gave me a mysterious smile.

“António, didn’t you work for a Portuguese man?”

“Yes.” He smiled. “He was a Mr. Manager, a good boss, treated me real good . . . ”

“Was that in Bié Province?”

“No. Right here in Luanda. I been here a long time, Son. . . . Even way back before you were born, Son.”

Sitting at the table, I waited for him to say something more. Comrade António was doing the kitchen chores. He was smiling, but he remained silent. Every day he had the same smell. Even when he’d bathed; he always seemed to have those kitchen smells. He took the water bottle, filled it with boiled water, and put it back in the fridge.

“But, António, I still want more water . . . ”

“No, Son, that’s enough,” he said. “Otherwise there won’t be any cold water for lunch and your mother will be upset.”

“But António . . . Don’t you think that everybody should be in charge of their own country? What were the Portuguese doing here?”

“Hey, Son! Back then the city was clean. . . . It had everything you needed, nothing was missing.”

“But, António, don’t you see that it didn’t have everything? People didn’t earn a fair wage. Black people couldn’t be managers, for example . . .”

“But there was always bread in the store, Son. The buses worked perfectly.” He was just smiling.

“But nobody was free, António . . . Don’t you see that?”

“Nobody was free like what? Sure they were free, they could walk down the street and everything . . . ”

“That’s not what I mean, António.” I got up from my seat. “It wasn’t Angolans who were running the country, it was the Portuguese . . . It can’t be that way.”

Comrade António was just laughing.

He smiled at my words, and seeing me full of passionate feeling, he said: “What a kid!” Then he opened the door to the yard, sought out Comrade João, the driver, with his eyes and told him: “This kid’s terrible!” Comrade João smiled, sitting in the shade of the mango tree.

Comrade João was the ministry driver. Since my father worked in the ministry, he helped with the family’s trips. Sometimes I took advantage of the lift and got a ride to school with him. He was thin and drank a lot so that once in a while he showed up very early in the morning already drunk, and nobody wanted to ride with him. Comrade António said that he was used to it, but I was afraid. One day he gave me a ride to school and we started to talk.

“João, did you like it when the Portuguese were here?”

“Like what, Son?”

“You know, before independence they were the ones who were in charge here. Did you like that time?”

“People say the country was different . . . I don’t know . . .”

“Of course it was different, João, but it’s different today, too. The comrade president is Angolan, it’s Angolans who look after the country, not the Portuguese . . .”

“That’s the way it is, Son . . .” João liked to laugh, too, and afterward he whistled.

“Did you work with Portuguese people, João?”

“Yes, but I was very young . . . And I was in the bush with the guerrillas as well . . .”

“Comrade António likes to say really great things about the Portuguese,” I said to provoke him.

“Comrade António is older,” João said. I didn’t understand very well what he meant.

As we passed some very ugly buildings, I waved to a comrade teacher. João asked me who she was, and I replied: “It’s Teacher María, that’s the complex of the Cuban teachers.”

He dropped me at the school. My classmates were all laughing because I’d got a lift to school. We gave anybody who got a ride a hard time, so I knew they were going to make fun of me. But that wasn’t all they were laughing about.

“What is it?” I asked. Murtala was talking about something that had happened the previous afternoon, with Teacher María. “Teacher María, the wife of Comrade Teacher Ángel?”

“Yes, that one,” Helder said, laughing. “Then this morning, over in the classroom, everybody was making a lot of noise and she tried to give a red mark to Célio and Cláudio . . . Oh! . . .They started to make tracks and the teacher said . . .” Helder was laughing so hard he couldn’t go on. He was all red. “The teacher said: ‘You get down here,’ or ‘there’ or something!”

“Yeah, and after that?” I was starting to laugh too, it was contagious.

“They threw themselves right down on the floor.”

We all busted ourselves laughing. Bruno and I liked to joke with the Cuban teachers as well. Since at times they didn’t understand Portuguese very well, we took advantage by speaking quickly or talking nonsense.

“But you still don’t know the best part.” Murtala came up to my side.

“What’s that?”

“She was crying and took off for home!” Murtala started laughing flat out as well. “She split just because of that.”

We had math class with Teacher Ángel. When he came in he was upset or sad. I signaled to Murtala, but we weren’t able to laugh. Before the class started the comrade teacher said that his wife was very sad because the pupils had been undisciplined, and that a country undergoing reconstruction needed a lot of discipline. He also talked about Comrade Che Guevara, he talked about discipline and about how we had to behave well so that things would go well in our country. As it happened, nobody complained about Célio or Cláudio, otherwise, with this business of the revolution, they’d have got a red mark.

At recess Petra went to tell Cláudio that they should apologize to Comrade Teacher María because she was really cool, she was Cuban and she was in Angola to help us. But Cláudio didn’t want to hear what Petra was saying, and he told her that he’d just followed the teacher’s orders, that she’d told them to “get down here,” and so they threw themselves on the floor.

We liked Teacher Ángel. He was very simple, very humorous. The first day of class he saw Cláudio with a watch on his wrist and asked him if the watch belonged to him. Cláudio laughed and said yes. The Comrade Teacher said in Spanish, “Look, I’ve been working for many years and I still don’t have one,” and we were really surprised because almost everybody in our year had a watch. The physics teacher was also surprised when he saw so many calculators in the classroom.

But it wasn’t just Teacher Ángel and Teacher María. We liked all the Cuban teachers, because with them classes started to be different. The teachers chose two monitors to help with discipline, which we liked at first because it was a sort of secondary responsibility (after that of class delegate), but later we didn’t like it very much because to be a monitor “it was essential to help the less capable compañeros,” as the comrade teachers said to us in Spanish, and you had to know everything about that subject and you couldn’t get less than an A.

At the end of the day the comrade principal came to talk to us. We liked it when someone came into the classroom because we had to pay attention and do that little song that most of us took advantage of to shout: “Good afternooooon . . . comraaaaade . . . principaaaaal!”

Then she told us that we would have a surprise visit from the comrade inspector of the Ministry of Education. She knew it was going to be some day soon and we had to behave well, clean the school, the classroom, the desks, come to school looking “presentable” (I think that’s what she said), and the teachers would explain the rest later.

Nobody said anything, we didn’t even ask a question. Of course we stood up only when the comrade principal said, “All right, until tomorrow,” and that “until tomorrow” wasn’t so offhand because it would be different if she said, “Until next week.”

So we stood up and said really loudly: “Untiiiiiiil . . . tomorrooooow . . . comraaaaade . . . principaaaaal!”

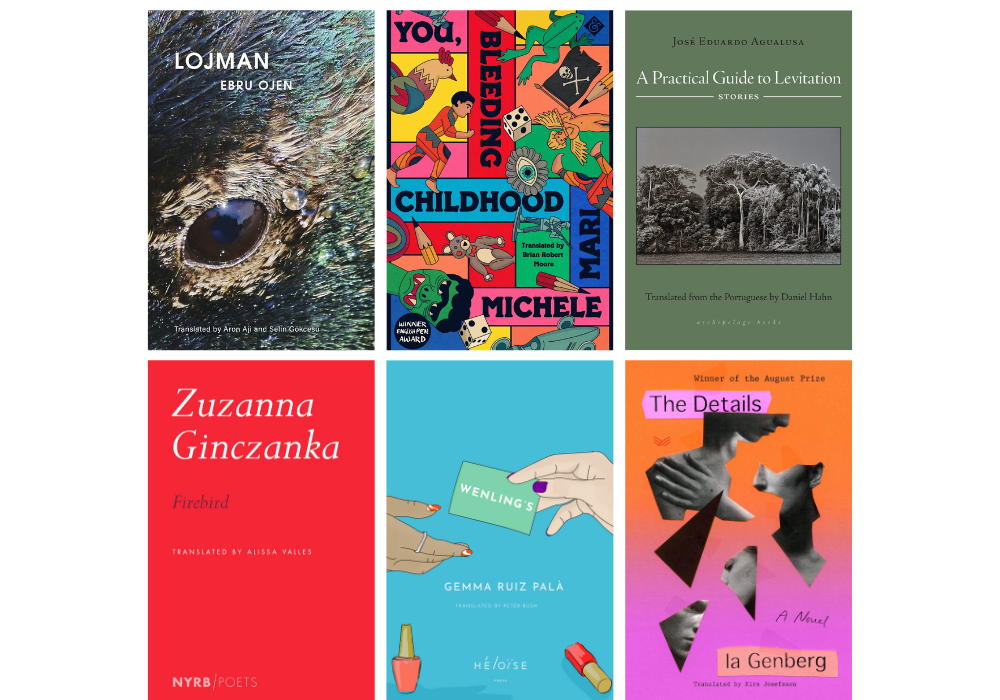

From Good Morning, Comrades! Forthcoming from Biblioasis. By arrangement with the publisher. First published 2000 as Bom dia camaradas. All rights reserved.